Key Points

- •

Ultrasound is the preferred initial screening modality for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

- •

The entire abdominal aorta should be imaged in two perpendicular planes (transverse and longitudinal) to avoid missing subtle abnormalities.

- •

Oblique imaging planes may underestimate or overestimate aortic diameter and should be avoided.

Background

The abdominal aorta is a vital retroperitoneal structure with the potential for catastrophic pathology that is often difficult to diagnose. In the words of Sir William Osler, “There is no disease more conducive to clinical humility than aneurysm of the aorta.” When a diagnosis of aortic pathology is identified, appropriate interventions may improve outcomes for this often time-sensitive presentation.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are the most commonly identified aortic abnormality. They may be complicated by thrombosis, dissection of the intimal layer, or rupture, which carries a particularly high mortality of approximately 90%. The incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysm increases with age, family history, male gender, and a history of smoking. The overall prevalence is approximately 4.7% and 3.0% in men and women, respectively. This peaks around 5.9% in men 80–85 years old and 4.5% for women over age 90.

Aortic pathology should be considered in any patient presenting with abdominal discomfort, especially in patients with known risk factors and those that present with classic histories or exam findings (hypotension, back pain, pulsatile abdominal mass). In addition, various recommendations have been made for screening asymptomatic patients, including a grade B recommendation by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, which recommends screening all men between the ages of 65–75 with a history of smoking.

Use of point-of-care ultrasound saves time, reduces cost, and avoids ionizing radiation and exposure to intravenous contrast when compared to other imaging modalities. Point-of-care ultrasound has demonstrated high sensitivity (97.5–100%) and specificity (94.1–100%) for detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm. It has high correlation with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosing aortic dilation, but may slightly underestimate the exact diameter.

Normal Anatomy

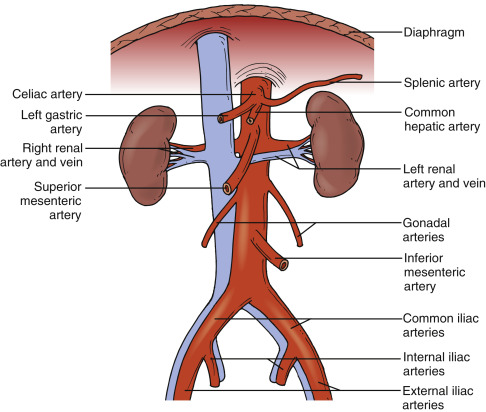

The abdominal aorta is the section of aorta that extends from the posterior diaphragm where it exits from the thoracic cavity and continues until its division into the common iliac arteries. Through the abdomen, its major branches include the left and right renal arteries, celiac artery, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, and gonadal arteries. In addition, it has branches to supply the diaphragm, adrenal glands, abdominal wall, and spinal cord. Figure 22.1 illustrates the major branches of the abdominal aorta.

Image Acquisition

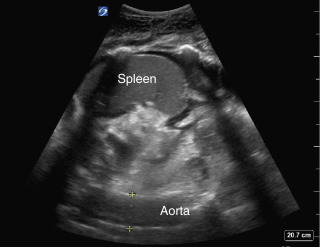

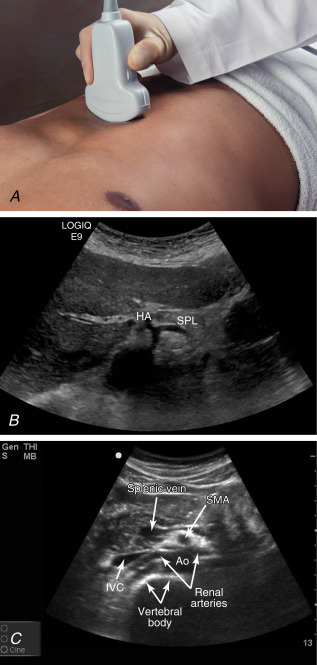

Sonographic visualization of the abdominal aorta is achieved through a transabdominal approach. The proximal aorta can be viewed in the transverse (short-axis) plane by placing a phased-array or curvilinear transducer (3.5–5 MHz) just below the costal margin in the center of the abdomen with the transducer marker pointing to the patient’s right. Commonly, the celiac artery and superior mesenteric artery are seen in this position, and occasionally left and right renal arteries may be identified ( Figure 22.2 and ![]() ). Evaluation of these structures is typically less important when assessing for the simple presence or absence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, but their identification provides useful landmarks. A particularly useful sonographic reference point is the vertebral body and its characteristic shadow, which lies immediately posterior and slightly to the right of the aorta.

). Evaluation of these structures is typically less important when assessing for the simple presence or absence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, but their identification provides useful landmarks. A particularly useful sonographic reference point is the vertebral body and its characteristic shadow, which lies immediately posterior and slightly to the right of the aorta.

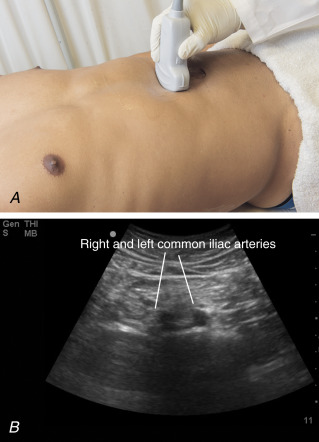

Once the aorta is identified in a transverse plane, slide the transducer inferiorly on the abdominal wall, allowing for contiguous imaging of the aorta. With the transducer in a transverse position just above the umbilicus with the ultrasound beam directed posteriorly, the distal aorta is visualized as it divides into the left and right common iliac arteries ( Figure 22.3 and ![]() ).

).

After evaluating the aorta in short axis, longitudinal views should be acquired to accurately assess the size of the aorta. Place the transducer over the proximal abdominal aorta and rotate the transducer clockwise 90 degrees so that the transducer marker is pointed toward the patient’s head. Again, it may be possible to visualize the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries if the plane of the ultrasound transducer is aligned with these vessels ( Figure 22.4 and ![]() ).

).

Measurements of the aortic diameter should be obtained in both transverse and longitudinal planes. It is important to measure the aortic diameter with the transducer perpendicular to the aorta to capture a true cross-sectional image because oblique images can underestimate or overestimate the diameter. Calipers should be placed on the outer edges of the aortic walls. The diameter of the aorta should be measured proximally and distally with calipers placed on the outer edges of the aortic walls.

If interpretable images cannot be obtained in the anterior mid-abdomen, usually due to bowel gas or scarring, then an alternate approach is to image the aorta laterally from the right or left flank. With the transducer marker pointing toward the patient’s head, place the transducer in the right or left midaxillary line just below the costal margin to capture longitudinal views of the aorta. From the right flank, a longitudinal view of two tubular, anechoic structures is seen posterior to the liver at the bottom of the image; the near-field structure is the inferior vena cava, and the deeper structure is the abdominal aorta. The transducer can be rotated 90 degrees clockwise to obtain transverse views of the aorta, but acquiring transverse images laterally can be challenging due to the depth of the aorta. The same technique can be used to obtain longitudinal views of the abdominal aorta from the left flank ( Figure 22.5 and ![]() ).

).