Key Points

- •

Ultrasound guidance for placement of central venous catheters reduces mechanical complications, including pneumothorax and arterial puncture, and has become the standard of care for placement in the internal jugular vein.

- •

A transverse or longitudinal approach can be used to insert central venous catheters with ultrasound guidance, similar to placement of peripheral venous or arterial catheters.

- •

Tracking the needle tip in real time is the primary skill that must be mastered to insert central venous catheters with ultrasound guidance.

Background

Use of ultrasound to guide central venous catheter insertion was first described in 1984. Initially, ultrasound was used to help locate the target vein when using the traditional landmark, or “blind,” technique. Even though studies concluded that ultrasound guidance may be beneficial, it was not clearly seen as the future technique of vascular access because it was felt to be too cumbersome and potentially too expensive.

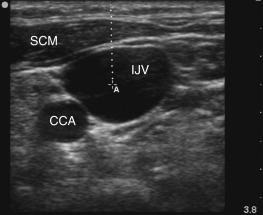

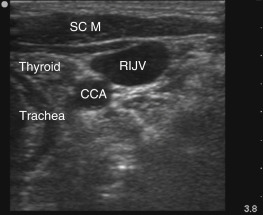

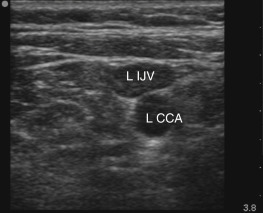

Over the past 25 years, ultrasound guidance for vascular access has evolved from use of Doppler ultrasound alone to use of high-frequency linear transducers that provide excellent resolution, thus allowing detailed visualization of vascular anatomy and adjacent structures. In the neck, the internal jugular vein and common carotid artery can be easily recognized with two-dimensional ultrasound and confirmed with Doppler ultrasound. Adjacent structures in the neck, such as the thyroid gland and trachea, can also be easily visualized.

Several studies have demonstrated that use of real-time ultrasound guidance for central venous catheter (CVC) insertion can increase success rates and decrease mechanical complications, primarily arterial puncture and pneumothorax. Use of real-time ultrasound guidance for insertion of CVCs has evolved to become the standard of care and is recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Institute of Medicine (IOM), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and several professional societies. Benefits of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion have expanded to include cost-effectiveness and reduction of catheter-related bloodstream infections. Very low rates of mechanical complications are now expected of providers.

Use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion is now widespread among most major medical centers. As provider confidence with use of ultrasound guidance for vascular access has increased, the spectrum of large and small vessels that can be accessed with ultrasound has also increased. Benefits of ultrasound guidance were initially proven with internal jugular vein cannulation, and use of ultrasound guidance is currently considered standard of care at this site. Subsequently, use of ultrasound guidance became routine for insertion of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), and currently, providers have started to recognize the benefits of ultrasound guidance for subclavian/axillary vein access. In response to delayed implementation of decade-old recommendations outlined in the Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System , two evidence-based consensus recommendations on ultrasound-guided vascular access technique and training have been published.

This chapter reviews the techniques for CVC insertion in the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein (proximal axillary vein) using real-time ultrasound guidance.

Internal Jugular Vein Catheterization

Anatomy

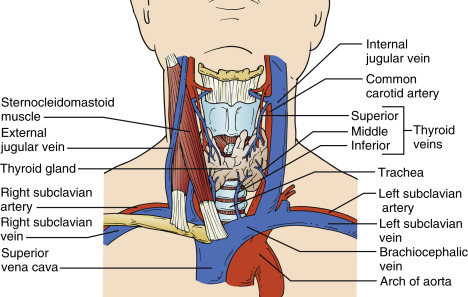

The internal jugular vein (IJV) runs vertically on the anterolateral side of the neck, lateral to the common carotid artery (CCA). The IJV joins the subclavian vein (SCV) to form the brachiocephalic, or innominate, vein that drains into the superior vena cava ( Figure 28.1 ). In the neck, CVCs are generally inserted into the IJV between the clavicular and sternal heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle ( Figure 28.2 ).

Technique

It is imperative to be familiar with the operation of the ultrasound machine before performing ultrasound-guided procedures. High-frequency, linear array transducers, often called vascular probes , are used for vascular access. The high-frequency waves give a high-resolution image to a maximum depth of 6-10 cm.

Preprocedural scanning of the left and right neck should be performed to determine the best site. Assess the internal jugular vein from the angle of jaw to the inferior anastomosis with the SCV ( ![]() ). Turn the patient’s head slightly about 30 degrees to the contralateral side with the neck extended. Evaluate the IJV’s size, shape, depth, compressibility, proximity to common carotid artery, and distal anastomosis with the SCV. Respirophasic variation of the size of the internal jugular vein can be noted (

). Turn the patient’s head slightly about 30 degrees to the contralateral side with the neck extended. Evaluate the IJV’s size, shape, depth, compressibility, proximity to common carotid artery, and distal anastomosis with the SCV. Respirophasic variation of the size of the internal jugular vein can be noted ( ![]() ). Center the IJV on the screen and slide the ultrasound transducer slowly toward the clavicle assessing for compressibility. Once the transducer cannot be advanced distally, tilt the transducer aiming the ultrasound beam toward the feet to assess the subclavian and brachiocephalic veins for patency. It is important to assess for complete compressibility of the IJV (

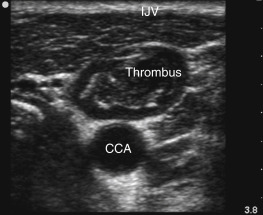

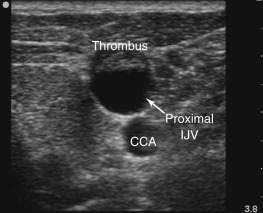

). Center the IJV on the screen and slide the ultrasound transducer slowly toward the clavicle assessing for compressibility. Once the transducer cannot be advanced distally, tilt the transducer aiming the ultrasound beam toward the feet to assess the subclavian and brachiocephalic veins for patency. It is important to assess for complete compressibility of the IJV ( ![]() ) because asymptomatic thrombosis is not uncommon in hospitalized and critically ill patients ( Figures 28.3 and 28.4 and

) because asymptomatic thrombosis is not uncommon in hospitalized and critically ill patients ( Figures 28.3 and 28.4 and ![]() ). In addition, patients that have had multiple prior IJV cannulations, especially with large caliber temporary hemodialysis catheters, may have a stenotic IJV from scarring on one side ( Figure 28.5 ).

). In addition, patients that have had multiple prior IJV cannulations, especially with large caliber temporary hemodialysis catheters, may have a stenotic IJV from scarring on one side ( Figure 28.5 ).

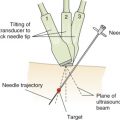

After the best insertion site has been determined, the ultrasound machine should be prepared. Position the ultrasound machine in the operator’s direct line of sight to allow viewing the screen without head turning. The transducer should be cleaned with antiseptic wipes, inserted in a sterile transducer cover, and then placed on the sterile field. The transducer should be held in the nondominant hand while the syringe with needle is held in the dominant hand. Orient the transducer in the nondominant hand so that the left side of the transducer corresponds with the left side of the screen. Two approaches to real-time needle guidance are described: transverse and longitudinal (see Figure 4.9 in Chapter 4, Orientation ).

Transverse Approach

In a transverse approach, the introducer needle crosses the plane of the ultrasound beam, and only the needle tip is seen. The shaft of the needle is not tracked. First, center the IJV in a transverse view on the screen and assess the depth to the vessel ( Figure 28.6 ). Tilt the transducer, pointing the ultrasound beam toward the operator. Insert the needle at a 45–60 degree angle relative to skin in the center of the long axis of the transducer ( Figure 28.7 ). Identify the needle tip on the screen by very subtly tilting the transducer. It is imperative to identify and track the needle tip. Advance the needle a few millimeters at a time while continuing to track the needle tip by subtly tilting the transducer back and forth (see Figure 4.10 in Chapter 4, Orientation ). Redirect the needle as needed if its trajectory is off target. As the skin is traversed as described above, the needle tip will be visualized denting the IJV ( ![]() ), followed by puncturing and entering the vessel ( Figure 28.8 and

), followed by puncturing and entering the vessel ( Figure 28.8 and ![]() ).

).