Chapter Outline

Gastric or duodenal ulcers (peptic ulcers) are thought to occur in about 10% of the adult population in the West. Peptic ulcers are important not only because of the frequent occurrence of pain or other symptoms, but also because of the morbidity and mortality associated with complications such as bleeding and perforation. It has been well established that Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have a major role in ulcer development. Duodenal ulcers are almost always benign, but a small percentage of gastric ulcers are found to be malignant, so gastric ulcers require careful evaluation and follow-up to differentiate benign from malignant lesions.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis

During the early 20th century, gastric ulcers were much more common than duodenal ulcers. Since that time, there has been a dramatic reversal of this relationship, so duodenal ulcers are now more common than gastric ulcers. Although duodenal ulcers occur in adults of all ages, gastric ulcers are found predominantly in patients older than 40 years. Regardless of their site of origin, peptic ulcers have an equal gender distribution. Gastric and duodenal ulcers are characterized by seasonal variations, with a higher frequency in spring and autumn and a lower frequency in summer.

A voluminous body of literature has shown convincingly that H. pylori and NSAIDs are responsible for the vast majority of gastric ulcers and that H. pylori is the causative agent for almost all duodenal ulcers. Nevertheless, H. pylori –negative ulcers may occasionally develop in the absence of NSAID use. Other possible causes of gastric ulcers include steroids, tobacco, alcohol, coffee, stress, duodenogastric reflux of bile, and delayed gastric emptying. Hereditary factors have also been implicated. These subjects are discussed separately in the following sections.

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis

H. pylori is a gram-negative, spiral bacillus that was first isolated on endoscopic biopsy specimens from the stomach by Warren and Marshall in 1983. Since then, H. pylori has been recognized as the major cause of gastric and duodenal ulcers. In various studies, the prevalence of H. pylori gastritis has ranged from 60% to 80% in patients with gastric ulcers and from 95% to 100% in patients with duodenal ulcers.

The mechanism whereby H. pylori predisposes to the development of ulcers remains uncertain. It has been shown that patients with H. pylori gastritis have increased secretion of gastrin, with high basal and peak acid outputs. As a result, a gastrin-mediated increase in gastric acid secretion may be a key factor in the pathogenesis of ulcers. Although most people with H. pylori never develop ulcers, more virulent strains of the organism are more likely to be associated with ulcer formation. In particular, a cagA -positive strain of H. pylori has been implicated in patients with duodenal ulcers and, to a lesser degree, gastric ulcers. Many of these patients also have evidence of gastric metaplasia at the borders of the ulcers, with infection of the metaplastic epithelium by H. pylori. The infected mucosa may therefore be more susceptible to ulceration.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

In various studies, the prevalence of gastric ulcers in patients treated with aspirin or other NSAIDs has ranged from 15% to 30%. It has been shown that NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandin production by blocking the formation of cyclooxygenase 1 (COX-1), a rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of prostaglandins. This phenomenon occurs even with aspirin doses as low as 10 mg daily (compared with a dose of 81 mg daily for cardiovascular prophylaxis). Because prostaglandins have cytoprotective properties, inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis can lead to mucosal injury and ulceration.

The development of gastric ulcers in patients on NSAIDs is also related to a topical effect caused by breakdown of the mucosal barrier. It has been shown that aspirin disrupts the mucus gel layer in the stomach, allowing acid to damage the gastric mucosa, even in the presence of normal or decreased acid secretion. Altered mucosal resistance is therefore thought to be a major factor in ulcer pathogenesis. Nevertheless, it has been shown that patients taking enteric-coated aspirin have the same risk of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding as those taking non–enteric-coated aspirin. Ulcers have also been induced in cats by intravenous (IV) infusion of aspirin. Thus, the development of ulcers is ultimately mediated by a combination of the topical and systemic effects of NSAIDs.

Chronic NSAID use is associated not only with an increased frequency of ulcers but also an increased frequency of complications such as perforation, obstruction, and bleeding. Studies have shown that people taking NSAIDs have a twofold to sixfold higher risk of developing these complications than those not taking NSAIDs. The risk increases even further in people over 60 years of age. A careful NSAID history should therefore be obtained in all patients with H. pylori– negative ulcers because of the likelihood that these ulcers are NSAID-related.

Steroids

Some investigators believe that steroids predispose to the development of ulcers, particularly gastric ulcers. This concern often results in discontinuation of steroids in patients with ulcer symptoms or GI bleeding. In a large study, however, patients receiving steroids were found to have the same frequency of ulcers as the general population. It is therefore questionable whether steroids have any role in ulcer pathogenesis. Nevertheless, steroids can mask the clinical findings associated with ulcers, so a large or even perforated ulcer may fail to produce symptoms in these patients.

Tobacco, Alcohol, and Coffee

Some investigators have found that cigarette smokers are more likely to have ulcers than nonsmokers and that perforated ulcers are also more likely to occur in these individuals. Others have found no significant correlation between smoking and ulcers. Although alcohol and coffee may stimulate acid secretion, their role in ulcer pathogenesis remains uncertain.

Stress

Some investigators believe that emotional stress contributes to the development of peptic ulcers by increasing peptic acid secretion. In one study, extreme emotional stress after a major earthquake in Japan resulted in an increased frequency of gastric ulcers, particularly bleeding ulcers. Others have found that stressful life events are no more common in patients with ulcers than in the general population. Thus, the role of stress in the development of ulcers remains uncertain.

Gastroduodenal Reflux of Bile and Delayed Gastric Emptying

Some patients with gastric ulcers have an unusually high concentration of bile acids in the stomach, so duodenogastric reflux of bile has been implicated in ulcer pathogenesis. Gastric stasis from gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis may also predispose to the development of gastric ulcers by prolonging exposure of the stomach to its own peptic secretions. The latter ulcers have been called Dragstedt ulcers based on the name of the investigator who described them.

Hereditary Factors

A small percentage of patients with peptic ulcers have a family history of ulcers. This familial aggregation of ulcers is explained primarily by hereditary rather than environmental factors because studies have found a much greater concordance of ulcers in monozygotic twins than in dizygotic twins. Patients with blood type O also have a higher incidence of ulcers than those with other blood types. Finally, peptic ulcers are more common in patients with genetic syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1, systemic mastocytosis, and tremor-nystagmus-ulcer syndrome. Thus, hereditary factors have clearly been implicated in the development of ulcers.

Clinical Findings

Patients with peptic ulcers often present with localized epigastric pain between the xiphoid cartilage and umbilicus. Ulcer pain tends to have a rhythmic nature; gastric ulcer pain typically occurs less than 2 hours after meals, whereas duodenal ulcer pain occurs 2 to 4 hours after meals and is more likely to wake the patient at night. Nevertheless, there is so much overlap in the timing of the pain that it is difficult to differentiate gastric and duodenal ulcers on clinical grounds.

Some patients with peptic ulcers may have right upper quadrant, back, or chest pain or other symptoms such as bloating, belching, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Depending on the clinical findings, the differential diagnosis may include reflux esophagitis, gastritis, duodenitis, cholecystitis, irritable bowel syndrome, ischemic bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, pancreatitis, and gastric or pancreatic carcinoma.

The diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease is complicated by the fact that patients with classic ulcer symptoms are not always found to have ulcers. Conversely, 25% to 50% of patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers are asymptomatic. These individuals may not seek medical attention until the development of potentially catastrophic complications such as perforation, bleeding, or obstruction. When ulcers on the posterior wall of the stomach or duodenum penetrate into the pancreas, the normally rhythmic epigastric pain associated with ulcers is replaced by a more constant pain that radiates to the back. In contrast, free perforation of a gastric or duodenal ulcer causes peritonitis. The major factors contributing to mortality in patients with perforated peptic ulcers include age older than 60 years and a delay of more than 24 hours from the time of diagnosis to the time of surgery.

Patients with antral, pyloric channel, or duodenal ulcers associated with edema, spasm, or scarring may present with postprandial nausea and vomiting related to gastric outlet obstruction. Other patients with pyloric channel ulcers may develop the so-called pyloric channel syndrome with severe postprandial epigastric pain relieved by vomiting.

Peptic ulcers are the most common cause of acute upper GI bleeding, accounting for about 50% of cases. Some patients have one or more episodes of massive hemorrhage, manifested by hematemesis, melena, or rectal bleeding, whereas others have chronic, low-grade bleeding, manifested by guaiac-positive stool or iron-deficiency anemia. Gastric ulcers are more likely to bleed than duodenal ulcers, probably because of the greater size of the ulcer craters and older age of the patients. When ulcers are found in the duodenum, however, postbulbar duodenal ulcers are more likely to be associated with upper GI bleeding (particularly massive bleeding) than those in the duodenal bulb. Bleeding from ulcers ceases spontaneously in about 80% of cases, but some form of therapy is required to control the bleeding in the remaining 20%.

Treatment

The treatment for peptic ulcers depends on the underlying cause. If H. pylori gastritis is confirmed by endoscopic biopsy specimens or by noninvasive tests such as a urea breath test, serologic test, or stool antigen test (see Chapter 30 ), there is strong evidence that eradication of H. pylori leads to more rapid healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers and a much lower rate of ulcer recurrence. Expert panels convened by the National Institutes of Health and American Digestive Health Foundation therefore concluded that all patients with H. pylori –related gastric or duodenal ulcers should receive combination therapy with antimicrobial and antisecretory agents. Various combinations of antibiotics and antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors) have been shown to be highly effective in eradicating H. pylori. As a result, these patients can literally be cured of their ulcer disease without need for long-term maintenance therapy with antisecretory agents, unless they become infected by another strain of the organism.

In the absence of H. pylori, H2 receptor antagonists have proved to be highly effective in accelerating healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers by suppressing acid secretion. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole are even more effective in suppressing acid secretion and accelerating ulcer healing by selectively inhibiting the gastric proton pump that controls the first step in the production of gastric acid. Because NSAID-related ulcers are associated with decreased synthesis of prostaglandins (see earlier), misoprostol (a synthetic prostaglandin E analogue) has been used to accelerate ulcer healing in these patients. Prostaglandins and prostaglandin analogues also decrease the risk of developing gastric ulcers in patients on NSAIDs. Sucralfate, colloidal bismuth, and carbenoxolone are other drugs that have been used to treat ulcers.

Surgery may be required for recurrent or intractable ulcers that fail to heal with medical therapy, for ulcer complications such as bleeding, obstruction, and perforation, and for ulcers that have equivocal or suspicious findings on barium studies or endoscopy. The most common operations include partial gastrectomy, vagotomy and pyloroplasty, and hyperselective vagotomy. These surgical procedures and their complications are discussed in Chapter 35 . Because of better diagnosis and medical treatment of peptic ulcers, the need for surgery in these patients has decreased considerably since the late 1960s.

Radiographic Findings

Gastric Ulcers

Examination Technique

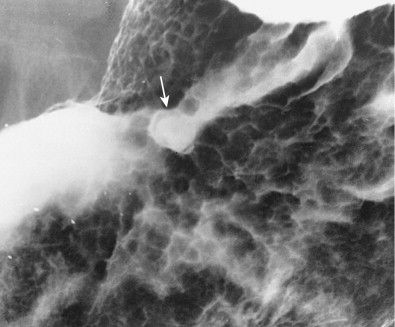

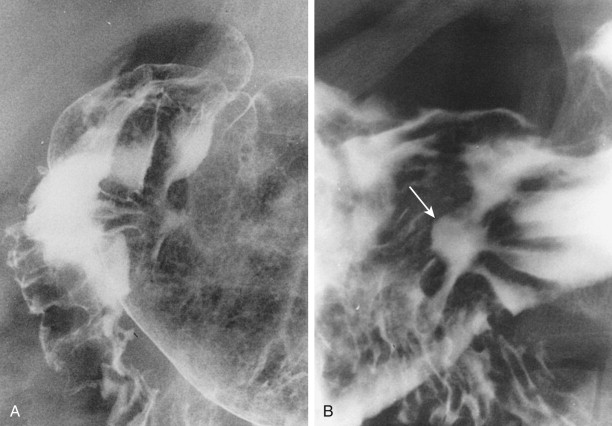

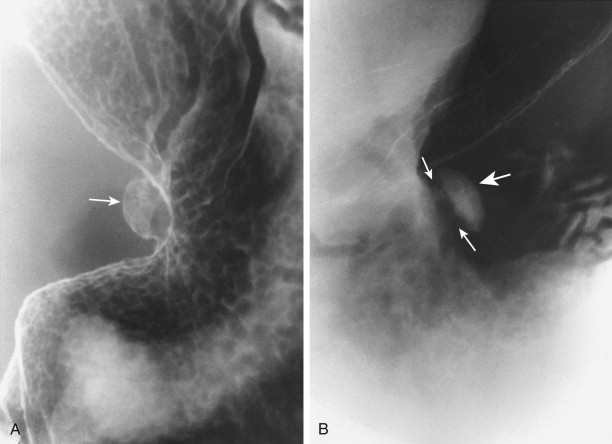

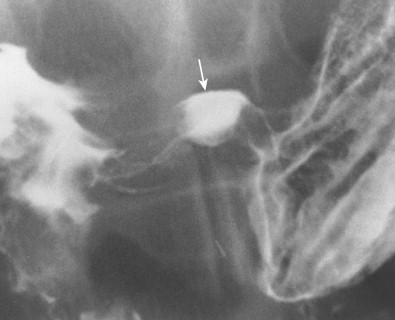

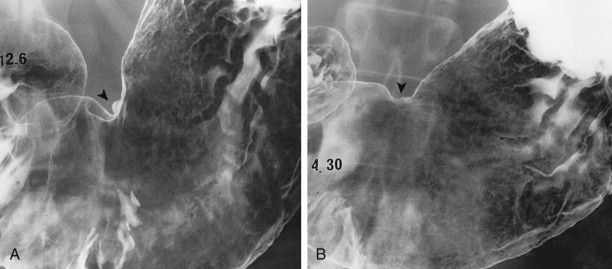

The double-contrast examination should be performed as a biphasic study that includes double-contrast views of the stomach with a high-density barium suspension and prone or upright compression views with a low-density barium suspension (see Chapter 17 ). Ulcer detection is facilitated by IV administration of 0.1 mg of glucagon to induce gastric hypotonia. Ulcers located on the posterior wall or on the lesser or greater curvature of the stomach are usually well seen on routine double-contrast views obtained with the patient in a supine or supine oblique position. Flow technique can be used to better delineate shallow ulcers on the posterior wall by slowly rotating the patient from side to side to manipulate a thin layer of high-density barium over the dependent surface ( Fig. 29-1 ). Upright compression views are also helpful for evaluating ulcers on the lesser curvature.

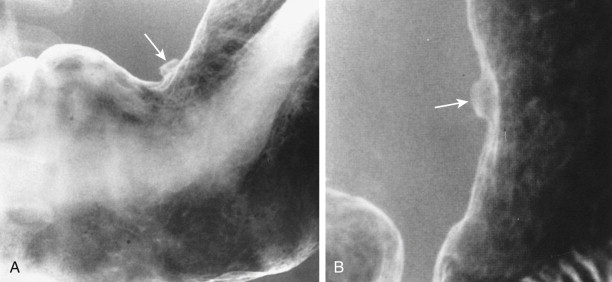

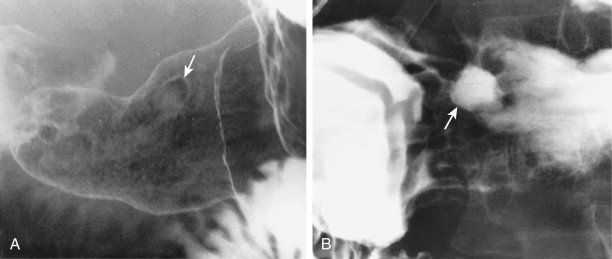

It is important to be aware of the limitations of double-contrast studies for detecting ulcers on the anterior (nondependent) wall of the stomach. Because of the effect of gravity, these ulcers may not fill with barium on double-contrast views with the patient in the usual supine or supine oblique position ( Fig. 29-2A ). Prone compression views of the gastric antrum and body should therefore be obtained routinely to demonstrate these anterior wall ulcers ( Fig. 29-2B ). Double-contrast views of the anterior wall can also be obtained by placing the patient in a prone Trendelenburg position.

Shape

Gastric ulcers are typically seen as round or ovoid collections of barium (see Figs. 29-1B and 29-2B ). Ulcer craters may have a variety of shapes and configurations, appearing as linear, rod-shaped, rectangular, serpiginous, or flame-shaped lesions ( Fig. 29-3 ). Linear ulcers constitute about 5% of all gastric ulcers diagnosed on double-contrast studies. These linear ulcers probably represent a stage of ulcer healing in the stomach and duodenum.

Size

The radiographic sensitivity in detecting gastric ulcers is related primarily to ulcer size; ulcers larger than 5 mm are more likely to be detected on barium studies. A major advantage of double-contrast technique is its ability to distend the stomach and efface normal folds, enabling visualization of small ulcers ( Fig. 29-4 ). Most gastric ulcers diagnosed on double-contrast studies are smaller than 1 cm. The high prevalence of small ulcers may also be related to the aggressive medical treatment that these patients often receive before undergoing radiologic investigations.

Large ulcers tend to be located more proximally in the stomach ( Fig. 29-5 ). These ulcers may occasionally be recognized on abdominal radiographs by the presence of gas in the ulcer crater. Giant gastric ulcers (ulcers > 3 cm in size) are associated with a higher risk of complications such as bleeding and perforation. However, most giant ulcers are found to be benign. Thus, the size of the ulcer crater has no relationship to the presence of carcinoma.

Location

Most benign gastric ulcers are located on the lesser curvature or posterior wall of the gastric antrum or body. In various studies, only 1% to 7% of benign ulcers were found to be located on the anterior wall and 3% to 11% on the greater curvature. In younger people, ulcers tend to be located in the antrum, whereas in older individuals, they are more likely to be located in the upper body, particularly on the lesser curvature. These high lesser curvature ulcers in older patients have been called geriatric ulcers.

Benign greater curvature ulcers are almost always located in the distal half of the stomach; the vast majority are caused by ingestion of aspirin or other NSAIDs. Because these ulcers rarely occur on the proximal half of the greater curvature, any ulcers in this location should be considered worrisome for malignant tumor until proved otherwise. Except for these ulcers high on the greater curvature, the location of the ulcer has no relationship to the presence of carcinoma.

Gastric ulcers are occasionally found in hiatal hernias. They tend to occur on the lesser curvature aspect of the hernia, where the hernia sac is compressed by the adjacent esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm (see Chapter 26 ). Because the hernia is inaccessible to palpation, double-contrast technique is particularly helpful for showing these ulcers.

Morphologic Features

Ulcers on the lesser or greater curvature are readily visualized in profile on barium studies, permitting analysis of the size, shape, and depth of the ulcer crater as well as associated findings such as radiating folds, Hampton’s line, or an ulcer mound or collar. Ulcers on the anterior or posterior wall may be difficult or impossible to visualize in profile, however, so these lesions must be evaluated on the basis of their appearance en face. In such cases, double-contrast technique is particularly helpful in assessing the surrounding mucosa for signs of benign or malignant disease.

Lesser Curvature Ulcers.

Ulcers on the lesser curvature typically appear as smooth, round or ovoid craters that project beyond the contour of the adjacent gastric wall ( Fig. 29-6 ; see Fig. 29-4 ). In some patients with lesser curvature ulcers, upright compression views may reveal a thin radiolucent line that separates barium in the ulcer crater from barium in the gastric lumen. This so-called Hampton’s line results from undermining of the mucosa surrounding the crater. In other patients, the rim of undermined mucosa may become more edematous, producing a wide radiolucent band, or ulcer collar (see Fig. 29-6B ). Occasionally, edema and inflammation surrounding the ulcer produces an ulcer mound, seen in profile as a smooth, bilobed, hemispheric mass projecting into the lumen on both sides of the ulcer. Ulcer mounds usually have poorly defined outer borders that form obtuse, gently sloping angles with the adjacent gastric wall. Hampton’s lines and ulcer mounds and collars are considered to be classic features of benign gastric ulcers, but these findings are present in only a small percentage of all patients with lesser curvature ulcers.

Retraction of the gastric wall adjacent to lesser curvature ulcers sometimes leads to the development of smooth, symmetric folds that radiate directly to the edge of the ulcer crater (see Fig. 29-6A ). Occasionally, these ulcers may be associated with retraction of the opposite wall, producing an incisura on the greater curvature. Other lesser curvature ulcers may be associated with focal enlargement of areae gastricae surrounding the ulcer because of edema and inflammation of the adjoining mucosa (see Fig. 29-6A ).

Greater Curvature Ulcers.

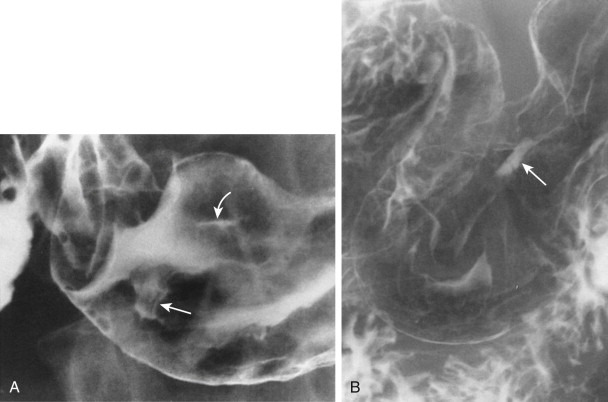

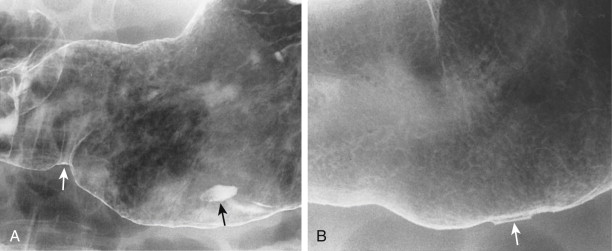

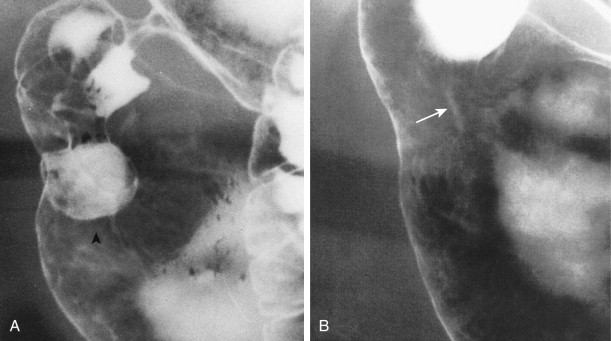

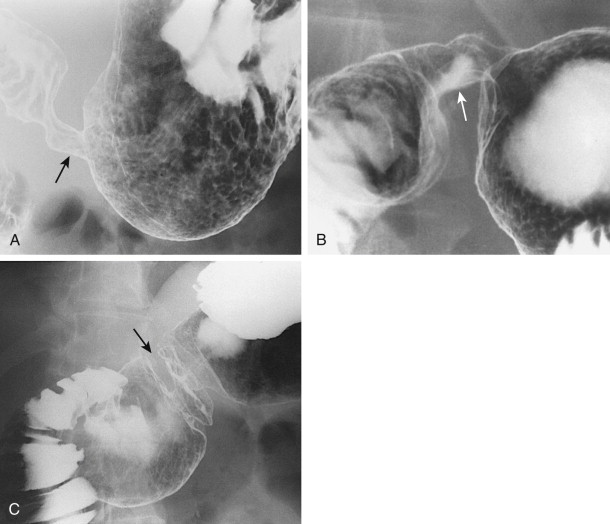

In the past, almost all ulcers on the greater curvature of the stomach were thought to be malignant. It is now recognized, however, that benign ulcers do occur on the distal half of the greater curvature in patients who are taking aspirin or other NSAIDs ( Figs. 29-7 and 29-8 ). The location of these ulcers on the greater curvature is presumably related to the effect of gravity because the dissolving aspirin tablets collect in the most dependent portion of the stomach, causing localized mucosal injury. Such lesions have been called sump ulcers because of their typical location on the greater curvature. A similar phenomenon may also account for the frequent finding of linear or serpiginous erosions in the body of the stomach, on or near the greater curvature in patients who are taking NSAIDs (see Chapter 30 ). Because of their location, greater curvature ulcers have a tendency to penetrate inferiorly into the gastrocolic ligament, occasionally leading to the development of a gastrocolic fistula (see later, “ Fistulas ”).

In contrast to ulcers on the lesser curvature, greater curvature ulcers may appear to have an intraluminal location because of circular muscle spasm and retraction of the adjacent gastric wall (see Fig. 29-8A ). Greater curvature ulcers may also be associated with considerable surrounding mass effect and thickened, irregular folds secondary to marked edema and inflammation accompanying the ulcers (see Fig. 29-8 ). Because of these morphologic features, benign greater curvature ulcers often have a suspicious radiographic appearance, so the usual radiographic criteria for differentiating benign and malignant ulcers elsewhere in the stomach are unreliable for ulcers in this location. Endoscopy and biopsy may therefore be required for some greater curvature ulcers, despite a history of aspirin ingestion.

Posterior Wall Ulcers.

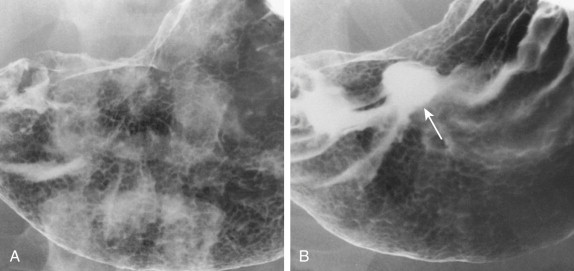

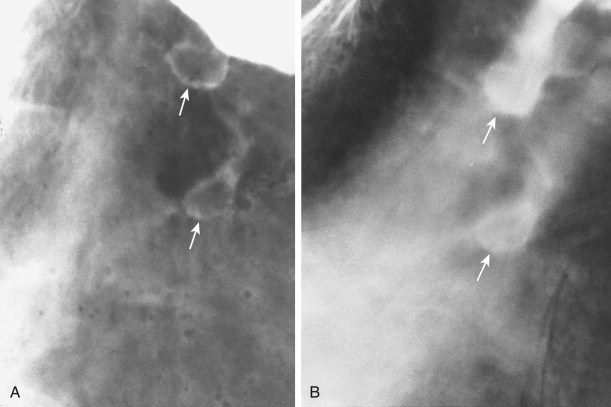

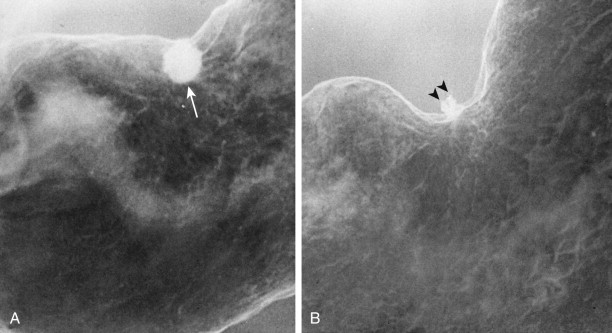

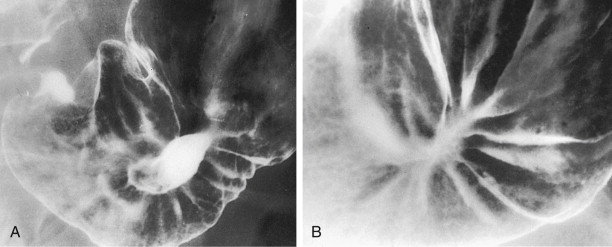

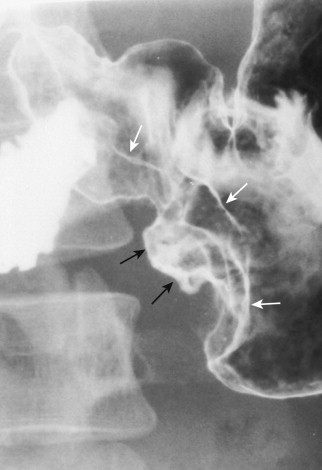

Ulcers on the posterior (dependent) wall of the gastric antrum or body may fill with barium on routine double-contrast views, producing the conventional appearance of an ulcer crater ( Fig. 29-9 ; see Fig. 29-1B ). However, shallow ulcers on the posterior wall may appear as ring shadows on these views because of a thin layer of barium coating the rim of the unfilled crater ( Fig. 29-10A ). In such cases, flow technique can be used to manipulate the barium pool over the surface of the ulcer and demonstrate filling of the ulcer crater ( Fig. 29-10B ). It is important not only to determine the size and shape of these posterior wall ulcers, but also to assess the appearance of the adjoining mucosa. Not infrequently, the areae gastricae are enlarged or distorted in the region of the ulcer because of surrounding edema and inflammation. An ulcer collar or mound can sometimes be seen en face as a radiolucent halo of edematous tissue with poorly defined outer borders that fade peripherally into the adjacent mucosa. Posterior wall ulcers may also be associated with a spectacular collection of folds that radiate directly to the edge of the ulcer crater. Occasionally, the edema and spasm associated with antral ulcers may cause such severe narrowing and deformity of the distal stomach that it is difficult to evaluate these ulcers by the usual radiologic criteria ( Fig. 29-11 ).

Anterior Wall Ulcers.

Ulcers on the anterior (nondependent) wall of the gastric antrum or body may also appear as ring shadows on routine double-contrast views because of barium coating the rim of the unfilled ulcer crater tangential to the central beam of the x-ray ( Fig. 29-12A ). In such cases, the ulcer may be shown by turning the patient 180 degrees into the prone position, so the ulcer is located on the dependent wall and fills with barium ( Fig. 29-12B ). Prone compression views of the stomach with low-density barium should therefore be obtained routinely to demonstrate these anterior wall ulcers.

Multiplicity

With double-contrast technique, multiple ulcers have been detected in about 20% of patients with ulcers or ulcer scars, a figure approximating the 20% to 30% prevalence of multiple ulcers at endoscopy, surgery, and autopsy. The presence of multiple ulcers is often thought to favor benign disease. In one study, however, 20% of patients with multiple gastric ulcers had malignant lesions. It is now recognized that patients may have coexisting benign and malignant ulcers, so each ulcer must be evaluated individually on barium studies.

When multiple gastric ulcers are present, they tend to be located in the gastric antrum or body (see Fig. 29-3A ). Multiple gastric ulcers are more likely to develop in patients who are taking aspirin or other NSAIDs (see Fig. 29-7A ). In one study, 80% of patients with multiple ulcers had a history of aspirin use. A careful drug history should therefore be obtained from these patients.

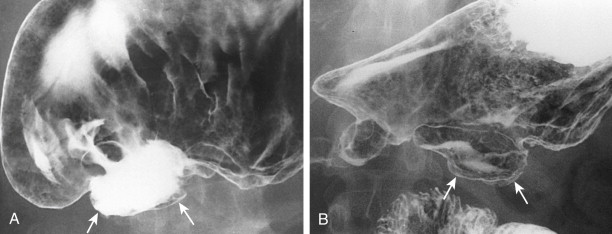

Ulcer Healing and Scarring

The radiologic assessment of ulcer healing is important for evaluating the success or failure of medical therapy and for confirming the presence of benign ulcer disease (see later, “ Benign Versus Malignant Ulcers ”). Ulcer healing may be manifested on barium studies not only by a decrease in the size of the ulcer crater but also by a change in its shape. Previously round or ovoid ulcers often have a linear appearance on follow-up studies, so linear ulcers presumably represent a stage of ulcer healing ( Fig. 29-13 ). Other ulcers may undergo splitting, so the ulcer crater is replaced by two separate niches at the periphery of the original ulcer ( Fig. 29-14 ). This phenomenon most likely occurs because healing and re-epithelialization are more rapid in the central portion of the ulcer than in the periphery.

Benign gastric ulcers usually have a marked response to treatment with antisecretory agents. The average interval between the initial barium study showing the ulcer and the follow-up study showing complete healing is about 8 weeks. Follow-up studies to demonstrate ulcer healing should therefore be performed after 6 to 8 weeks of medical treatment because studies performed sooner are unlikely to show complete healing.

In general, complete radiologic healing of a gastric ulcer has been considered a reliable sign that the ulcer is benign. Rarely, complete healing of malignant ulcers may occur with medical therapy. However, nodularity of the ulcer scar or irregularity, clubbing, or amputation of radiating folds should suggest the possibility of an underlying malignant tumor. The surrounding gastric mucosa must therefore be evaluated carefully after ulcer healing has occurred. If suspicious findings are present, endoscopy and biopsy are still required to rule out a malignant lesion.

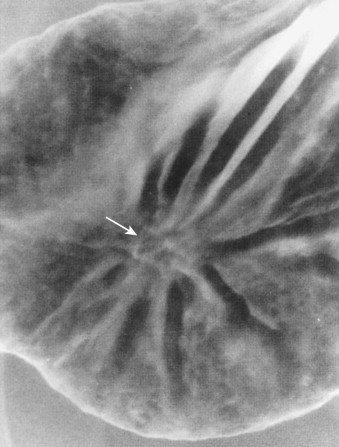

Ulcer healing may lead to the development of ulcer scars, which are visible on double-contrast studies in 90% of patients with healed gastric ulcers. These scars are usually manifested by a central pit or depression, radiating folds, and/or retraction of the adjacent gastric wall. The location of the ulcer is a major determinant of the morphologic features of the scar. Healing of ulcers on the lesser curvature is often associated with the development of relatively innocuous scars, manifested by slight flattening or retraction of the adjacent gastric wall ( Fig. 29-15 ). In contrast, healing of ulcers on the greater curvature or posterior wall is sometimes associated with the development of a spectacular collection of radiating folds ( Fig. 29-16 ). The folds may converge to a central point or to a circular or linear pit or depression ( Fig. 29-17 ). This central depression can be mistaken radiographically for a shallow, residual ulcer crater. However, the central depression of an ulcer scar tends to have more gradually sloping margins than an ulcer crater and should remain unchanged on sequential follow-up studies. A re-epithelialized ulcer scar can also be differentiated from an active ulcer by the presence of normal areae gastricae within the central portion of the scar ( Fig. 29-18 ).

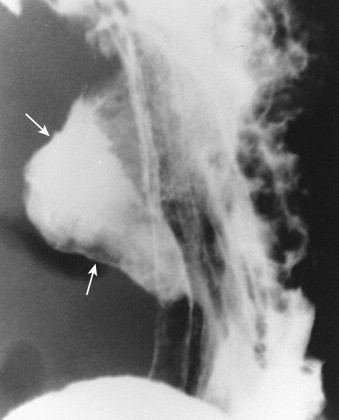

Healing of antral ulcers may also lead to the development of a prominent transverse fold that can be mistaken for an antral web or diaphragm. In other patients, severe scar formation may be manifested by antral narrowing and deformity ( Fig. 29-19A ). The narrowed segment usually has a smooth, tapered appearance, but asymmetric scarring may result in flattening and shortening of the lesser or greater curvature, so the pylorus has an eccentric location in relation to the antrum and duodenal bulb ( Fig. 29-19B ). Occasionally, an ulcer scar may be associated with such irregular antral narrowing that it mimics the linitis plastica appearance of a primary scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach. When antral scarring cannot be differentiated from a scirrhous carcinoma on radiologic criteria, endoscopy and biopsy are required for a more definitive diagnosis. Healing of ulcers on the lesser curvature of the gastric body may also lead to marked retraction and deformity of the opposite wall, producing a deep incisura on the greater curvature. Rarely, scarring of the gastric body may result in the development of a so-called hourglass stomach with marked circumferential narrowing of the gastric body ( Fig. 29-19C ).

Benign Versus Malignant Ulcers

More than 95% of gastric ulcers diagnosed in the United States are found to be benign. Nevertheless, radiologic examinations are often thought to be unreliable in differentiating benign ulcers from ulcerated carcinomas. Early reports indicated that 6% to 16% of gastric ulcers that appeared benign on conventional single-contrast barium studies were malignant. Although these studies were performed between 1955 and 1975, many gastroenterologists have used these data as the justification for performing endoscopy and biopsy on all patients with radiographically diagnosed gastric ulcers to rule out gastric carcinoma.

With double-contrast techniques, it is possible to obtain a far more detailed study of the mucosa surrounding the ulcer for signs of malignancy, such as irregular mass effect, nodularity, rigidity, and mucosal destruction. Several studies have found that almost all gastric ulcers with an unequivocally benign appearance on double-contrast examinations are benign lesions. In those studies, about two thirds of all benign ulcers had a benign radiographic appearance, so unnecessary endoscopy can be avoided in most patients with gastric ulcers diagnosed on double-contrast examinations. This finding has important implications for the evaluation of gastric ulcers because barium studies are safer and less expensive than endoscopy.

Unequivocally benign gastric ulcers are characterized en face by a round or ovoid ulcer crater surrounded by a smooth mound of edema or regular, symmetric folds that radiate directly to the edge of the crater (see Figs. 29-9, 29-13A, 29-14A, and 29-16A ). The areae gastricae adjacent to the ulcer may be enlarged as a result of inflammation and edema of the surrounding mucosa (see Fig. 29-6A ). When viewed in profile, benign gastric ulcers project outside the gastric lumen and are sometimes associated with a smooth, symmetric ulcer mound or collar or with smooth, straight folds that radiate to the edge of the ulcer crater (see Figs. 29-4, 29-6, and 29-15A ).

In contrast, malignant ulcers are characterized en face by an irregular ulcer crater eccentrically located within a discrete tumor mass. There may be focal nodularity of the surrounding mucosa or distortion or obliteration of adjacent areae gastricae because of tumor infiltrating this region. Although radiating folds may be present, they are often nodular, clubbed, fused, or amputated because of infiltration of the folds by tumor ( Fig. 29-20 ). When viewed in profile, malignant ulcers do not project beyond the expected gastric contour, and there is often a discrete tumor mass that forms acute angles with the adjacent gastric wall rather than the obtuse, gently sloping angles expected for a benign mound of edema ( Fig. 29-21 ).

Equivocal ulcers are those that have mixed features of benign and malignant disease, so a confident diagnosis cannot be made on radiologic criteria. For example, edema and inflammation surrounding a benign ulcer may result in enlarged, distorted areae gastricae, mass effect, or thickened, irregular folds, producing an indeterminate radiographic appearance ( Fig. 29-22 ). Similarly, NSAID-induced greater curvature ulcers that have an apparent intraluminal location or substantial associated mass effect and shouldered edges may result in equivocal radiographic findings (see Fig. 29-8A ). Most ulcers that have an equivocal appearance are ultimately found to be benign lesions. Nevertheless, it seems prudent to err on the side of caution by suggesting the possibility of malignant tumor for some benign lesions to avoid missing an early cancer.