2.1 Sclerotic Changes

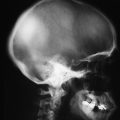

2.1.1 Case 1 (Fig. 2.1)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 24-year-old woman with syndromic epilepsy underwent cranial MRI that showed generalized thickening of the cranial vault. A CT examination was then ordered for further investigation of the bony changes. The experienced radiologist made the correct interpretation (below), but she sought consultation due to the unusually pronounced changes.

Radiologic Findings

The principal finding on MRI (Fig. 2.1 a) is a large, left-sided arachnoid cyst. The CT scout view (Fig. 2.1 b) shows cloudy areas of increased attenuation that are most conspicuous in the frontal and high parietal areas. Axial CT scans (Fig. 2.1 c–e) show variable, generalized thickening of the inner table. The outer table appears normal and the diploë is intact.

Location

The principal changes are confined to the inner table.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The sectional images identify the findings as primary bone changes and not as meningeal hyperostosis. Contrast-enhanced MR images (not pictured here) did not show meningeal enhancement.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes. This case represents an incidental finding in an MRI examination for syndromic epilepsy. The patient had no complaints (e.g., bone pain) that might be referable to the bone findings. The “harmonious” thickening and increased density of the inner table are consistent with a long-standing process.

Trauma?

No. At least the patient was not known to have had any serious falls, so it would be unrealistic to suggest patchy meningeal calcifications secondary to recurrent subdural bleeds (hemorrhagic pachymeningitis; Fig. 2.2, see following section Synopsis and Discussion). This pathogenesis would also imply a complete “obliteration” of the subdural space, probably resulting in impaired drainage. But the MRI shows no evidence of this.

Inflammation?

The history is negative for an inflammatory process. Moreover, it is difficult to imagine a generalized osteitis confined to the inner table and not involving the diploë.

Tumor?

No. One might consider a plaque-like meningioma growing in and on the bone, but contrast-enhanced MRI shows no evidence of a meningeal process (compare with Case 2 and Case 3). Fibrous dysplasia (see also Case 4 and Case 7) is unlikely to cause hyperostosis limited to the inner table; it would almost always involve both the inner and outer tables with expansion of the intervening space.

Synopsis and Discussion

The correct diagnosis is diffuse hyperostosis cranialis interna (diffuse calvarial hyperostosis), which is not an uncommon incidental finding, especially in pre- and postmenopausal women, and can be classified as a normal variant. The hyperostotic changes are especially pronounced in both the cranial vault and the phalanges in Morgagni syndrome, which occurs in postmenopausal women and is combined with obesity and hirsutism. The 24-year-old patient had undergone premature menopause, apparently related to her complex syndromic epilepsy. The pathogenesis of the hyperostosis is not fully understood but is definitely the result of an altered hormonal status.

Fig. 2.2 illustrates an old, ossified subdural hematoma for comparison. When questioned closely, this 47-year-old woman recalled that she had suffered a head injury many years ago. The plain radiographs (Fig. 2.2 a, b) show an area of increased density in the right frontoparietal region, which appears on CT (Fig. 2.2 c, d) as an ossified mass abutting the inner table but not fused with it. T1-weighted MRI shows no enhancement after contrast administration (Fig. 2.2 e, f). The ossification is very mature and consists of cancellous bone that apparently contains a medullary cavity with fatty tissue. This explains the high signal intensity in T1-weighted images.

Final Diagnosis

Diffuse hyperostosis cranialis interna relating to precocious menopause.

Comments

Even pronounced skeletal changes can still be classified as a normal variant when they are asymptomatic and are encountered with some frequency.

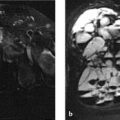

2.1.2 Case 2 (Fig. 2.3)

Case description

Referring physician: oncologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 61-year-old woman presented with a painless swelling in the left temporo-sphenoidal region. She had been treated for right breast cancer 10 years earlier. Question: metastasis, Paget disease with sarcomatous transformation, or fibrous dysplasia?

Radiologic Findings

The CT images (Fig. 2.3 a–f) show pronounced hyperostosis of the inner table with a normal-appearing outer table and intact diploë, similar to Case 1. In addition an unstructured, massive sclerotic lesion with marginal spiculations is visible in the left sphenoid bone and temporal bone. The spicules represent sites of new bone formation along vascular pathways. The scans also show marked swelling in the displaced masseter muscle. These findings are consistent with an active process that is quite unlike the generalized hyperostosis affecting the inner table. Contrast-enhanced MRI (Fig. 2.3 g, h) shows a very hyperintense (enhancing, therefore well-perfused) elliptical mass toward the meningeal side with concomitant enhancement of the osseous lesion, especially in its outer portion.

Location

The clinically symptomatic lesion in the left sphenoid bone and temporal bone is closely related to the adjacent mass showing meningeal enhancement.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The imaging findings show a definite relationship between the dural or meningeal mass and the osseous changes. This means that a meningeal neoplasm has apparently spread to the adjacent bone and has induced the formation of vascularized new bone along its margin. The fact that the meningeal mass has a convex boundary with the osseous lesion would not be consistent with contiguous meningeal invasion by a primary bony process (e.g., osteosclerotic metastasis or a bone-producing tumor).

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

The diffuse hyperostosis of the inner table ranks as an incidental finding in the postmenopausal patient, but not the active hyperostotic process with associated swelling in the left sphenoid bone and temporal bone.

Trauma?

The patient has no apparent history of acute or chronic trauma involving the affected region in the left sphenoid bone and temporal bone.

Inflammation?

No. A chronic inflammation in the form of osteitis would have been painful, and imaging would probably have shown sequestra or (on MRI) abscess formation. The meningeal mass is solid and shows no signs of an inflammatory process. Serologic inflammatory markers were normal in this patient.

Tumor?

For the sclerotic process in the left temporo-sphenoidal region: yes.

Synopsis and Discussion

The left temporo-sphenoidal process is most consistent with a sphenoid meningioma that has invaded the adjacent bone. Not infrequently, the intraosseous spread of meningioma is a painless process. The sphenoid region is a site of predilection for meningiomas, and the tumor cells stimulate metaplastic new bone formation. All of these factors are present in this case. The diagnosis of sphenoid meningioma is confirmed by contrast-enhanced MRI, which shows massive enhancement of the dura bordering the osseous lesion.

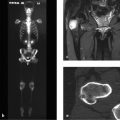

The other hyperostotic changes in the inner table are interpreted as a harmless variant (see under “Normal variant or malformation” above and Case 1) and have nothing to do with the intraosseous neoplastic process. This excludes a diagnosis of Paget sarcoma, since the bony cranium shows no signs of Paget disease. Paget sarcoma is generally lytic and not sclerotic, and other osseous changes typically affect the full cross-section of the bone. Although the referring physician suggested that the diffuse hyperostosis of the inner table may have been due to fibrous dysplasia, we can exclude that diagnosis because fibrous dysplasia generally affects both the inner and outer tables and expands the volume of the affected cranial bone. If we were to consider the sclerosing temporo-sphenoidal process in isolation, disregarding the adjacent meningeal focus, we might entertain the possibility of an osteosclerotic (osteoblastic) metastasis (Fig. 2.4) from breast cancer, for example—but that would be inconsistent with the convex interface of the meningeal neoplasm with the adjacent bone. Finally, one might consider a frequent catch-all diagnosis for sclerotic changes in the skull, namely chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis (Garré), but there appears to be little justification for the existence of this entity, which was described by Garré16 120 years ago!

The tumor was completely removed along with the affected dura and bone (Simpson 1). It was identified histologically as meningioma. The swelling of the masseter muscle is considered a reactive phenomenon.

Final Diagnosis

Sphenoid wing meningioma with intraosseous spread (histologically confirmed). Diffuse hyperostosis of the inner table, predominantly affecting the frontoparietal area, was noted as an incidental finding.

Comments

Two prominent radiologic findings should not necessarily be placed in the same category. The principle of “reverse Ockham’s razor” (see) does not apply in the present case. It is more accurate to interpret one of the findings as the principal diagnosis, which requires surgery, while interpreting the other finding as an incidental normal variant.

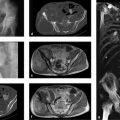

2.1.3 Case 3 (Fig. 2.5)

Case description

Referring physician: general surgeon.

Prior history and clinical question: A 37-year-old woman presented with a bony-hard protuberance in the left high parietal area, which she claimed had been present since puberty but had recently enlarged. She complained of occasional paroxysmal headaches at that location. On specific questioning, she described several other anatomic anomalies: a double uvula, double gallbladder, and malpositioned teeth. CT scans were interpreted as being suspicious for a bone tumor (e.g., fibrous dysplasia, hemangioma, metastasis).

Radiologic Findings

CT scans (Fig. 2.5 b, c) demonstrate an expansile osteosclerotic process in the high parietal region involving all three layers of the bone. Bony spicules are visible at the periphery of the raised area. The process shows very high uptake on bone scintigraphy (see Fig. 2.5 a). The author ordered contrast-enhanced MRI (see Fig. 2.5 d, e), which shows a spindle-shaped, intensely enhancing dural mass located just deep to the expanded bone area.

Location

The high parietal bony lesion directly overlies the dural mass.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The findings suggest an active, bone-producing mass that appears to have high peripheral vascularity, as evidenced by the presence of bony spicules (see under Radiologic Findings in Case 2). It is reasonable to assume that the bony lesion is related to the meningeal soft-tissue mass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree