3.1 Mono- and Bisegmental Changes

3.1.1 Case 17 (Fig. 3.1)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 28-year-old man presented with posterior neck pain on yawning and occasional dysphagia with no other complaints. His personal and family history was otherwise normal. The referring radiologist submitted the MR images and requested identification of changes noted in the C1 and C2 vertebrae.

Radiologic Findings

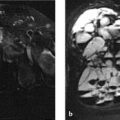

The MR images after intravenous (IV) contrast administration (Fig. 3.1 a, b) show lobulated masses with very low signal intensity located in and around the craniovertebral joints.

Location

Multicentric processes located in and around the bones of the craniovertebral joints.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The pathoanatomic background cannot reasonably be interpreted based on the MR images alone. Very likely, however, the findings represent an ossifying process.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Accurate interpretation of the MRI findings requires projection radiographs and CT scans using methods that directly visualize the bone (Fig. 3.1 c–e).

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes. The lobulated masses are located in the right half of the atlas, the dens, and the right arch of the atlas. They are solid, smoothly marginated, and have no discernible soft-tissue component. They resemble a multicentric extra- and intraosseous osteoma that appears to flow down uniformly in and on the bone. This in itself suggests a diagnosis of melorheostosis.

Trauma?

No, the history is negative for trauma. Otherwise we might consider old myositis ossificans, but CT in that case would show spongy bone rather than compact bone (see Case 30). Moreover, myositis ossificans does not involve the interior of a bone.

Inflammation?

No, the history is negative and the process has no destructive features.

Tumor?

Solid ossifications do occur in paraosseous osteosarcoma, but this tumor is a more coherent mass that does not resemble flowing candle wax on the cortex. A classic paraosseous osteosarcoma is typically painful and occurs almost exclusively on the metaphyses and metadiaphyses of the long bones (see Fig. 7.27 in Case 144) with a predilection for the popliteal surface of the femur (50–70% of all cases). The involvement of two bones (in our case, C1 and C2) is extremely unusual. Also, the unilateral involvement does not suggest a tumor.

Synopsis and Discussion

The correct diagnosis is melorheostosis at a somewhat unusual location. Biopsy is unnecessary. The disease, associated with typical epi- and endosteal ossification, occurs sporadically and most likely results from a postzygotic mutation that interferes with embryonic metameric differentiation. This accounts for the typical radial and segmental pattern of unilateral involvement. The term “melorheostosis” is derived from the Greek melos (limb) and rheos (flow) and fittingly describes the characteristic finding of ossifications that appear to flow down the outer and inner sides of the involved bone. In over 60% of cases the disease is associated with variable skin lesions, subcutaneous fibrosis, muscle contractures, and vascular malformations. We described five different basic radiologic patterns in 23 cases,23 and since then we have confirmed these results in more than 40 cases:

Osteoma-like form

Classic “flowing candle wax” form

Myositis ossificans–like ossifications, especially near joints

Osteopathia striata–like form

Mixed forms

Two additional cases with an unusual spinal location are presented in Fig. 3.2 (47-year-old woman, incidental finding) and in Fig. 3.3 (30-year-old woman, incidental finding). Note again the segmental unilateral distribution of the ossifications.

Final Diagnosis

Melorheostosis in C1 and C2.

Comments

Lesions that correspond ontogenetically to specific anatomic structures (in this case a segmental, unilateral distribution of ossifications) are very suspicious for a developmental anomaly and make an inflammatory or neoplastic process unlikely. Because melorheostosis has a nonspecific histology, a correct radiologic diagnosis is of crucial importance!

3.1.2 Case 18 (Fig. 3.4)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 57-year-old man underwent a routine checkup in which ultrasound detected a hepatic lesion (incidentaloma). Subsequent CT scans revealed (again incidentally) an intraosseous lesion in the T11 vertebral body. Further investigation of this lesion by CT, MRI, and scintigraphy raised suspicion of an atypical osteoma. The radiologist requested a consult to confirm this diagnosis.

Radiologic Findings

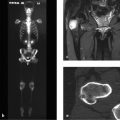

Whole-body bone scans (Fig. 3.4 a) show moderately increased uptake in the T11 vertebra. Axial CT scans (Fig. 3.4 b, c) show an extremely dense mass in T11 with small spicules radiating into the surrounding cancellous bone (Fig. 3.4 c). As the sagittal (Fig. 3.4 d, e) and coronal reformatted CT images (Fig. 3.4 f) demonstrate, the “white” mass contains a bicentric lucent area, the upper portion of which has a sclerotic margin. The lucent area on CT shows increased signal intensity in the STIR (short-tau inversion recovery) sequence (Fig. 3.4 g) and after IV contrast administration (Fig. 3.4 i), while in T1-weighted (T1w) images (Fig. 3.4 h) it is isointense to spinal cord. The signal intensity surrounding the mass is very slightly increased (Fig. 3.4 g).

Location

The bony mass is located predominantly in the posterior half of T11. The lower portion of the lesion is located at the center of the vertebral body while its upper portion is more posterosuperior. The lower portion of the mass is very closely related to the nutrient canal (Hahn cleft) through which blood vessels enter and exit the vertebra.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The “white” mass on CT represents solid (compact) bone with very little bone turnover, as indicated by only moderately increased uptake on the bone scan. The lucencies in the mass may correspond to vascular structures.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

No, this type of entity is not known to occur as a normal variant. A smaller version of the lesion could be a bone island (enostosis), which is one of the most common incidental findings in skeletal radiology (see also Case 5).

Trauma?

No, the history is negative for spinal trauma.

Inflammation?

No, the lesion was detected incidentally and the history is negative.

Tumor or tumorlike lesion?

Yes, if we include osteoma and giant osteoma among the benign bone-forming tumors.

Synopsis and Discussion

The following findings are suggestive of a giant osteoma:

Location in cancellous bone

Very high lesion density consistent with compact bone in the trabecular meshwork (hence the term “bone island”)

Fine spicules that “anchor” the lesion in the cancellous bone

Relatively low uptake on bone scintigraphy (small osteomas show no uptake at all, while larger lesions show low to moderate uptake—even though the lesions participate in normal, continuous bone remodeling, but apparently at a low level)

Incidental finding

The bicentric or dumbbell-shaped lucency in the lesion most likely represents vascular channels. It is not unusual to detect relatively large vessels in giant osteomas. In the present case they may be collateral vessels if we assume that the slow-growing osteoma occluded the central vascular system in the Hahn cleft. This could also account for the slightly increased signal intensity surrounding the osteoma, which may be interpreted as mild congestive edema.

We can exclude a malignant bone-forming tumor because the lesion is asymptomatic and shows only slight local bone metabolism. This means that the lesion does have a physiologic basic metabolism necessary for its nutrition but does not produce new tumorous bone—which would be a criterion for osteosarcoma, for example.

We might also consider melorheostosis, but this is not consistent with the central location of the lesion relative to the coronal plane. Melorheostosis also tends to be unilateral (see Case 17).

The lesion is too dense for a giant notochordal hamartoma (see Case 19).

A biopsy is unnecessary, especially since biopsies from lesions of such high density are generally nondiagnostic.

Final Diagnosis

Giant osteoma in T11, detected as an incidental finding.

Comments

A relatively large mass of compact bone density located within trabecular bone is generally a large osteoma, especially if it is detected incidentally and shows little tracer uptake on bone scans. Giant osteomas may contain vascular channels.

3.1.3 Case 19 (Fig. 3.5)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 55-year-old woman underwent a “routine MRI” of the cervical spine, which showed a signal abnormality in C2. Further investigation by CT and 18F-FDG PET showed changes that were suspicious for, among other things, a giant notochordal hamartoma.

Radiologic Findings

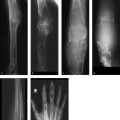

C2 has no signal in the T1w image (Fig. 3.5 a). It is minimally hyperintense to adjacent vertebral bodies in the T2w image (Fig. 3.5 b) but shows uniformly high signal intensity in the coronal STIR image (Fig. 3.5 c). C2 appears sclerotic on sagittal CT (Fig. 3.5 d). It appears as a cold lesion on 18F-FDG PET (arrow in Fig. 3.5 e, which is a magnified view from Fig. 3.5 f).

Location

Lesion is confined to C2.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

C2 has become involved by a process associated with new bone formation (reactive, reparative, tumor matrix?). The fact that the process is negative on 18F-FDG PET suggests that it is now inactive and that the sclerotic changes are old (no regional increase in blood flow, no measurable regional bone turnover). The sclerosis must still have an active soft-tissue component, however, otherwise we could not explain the relative proton abundance on MRI.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

This type of finding has not been previously described as a normal variant or malformation.

Trauma?

No, the patient gave no trauma history.

Inflammation?

Yes, in principle. The findings may result from an old, nonspecific, nondestructive inflammatory process that healed with sclerosis. But this does not necessarily explain the relative abundance of protons in C2, which is also at odds with the negative bone scan.

Tumor?

Yes, and apparently an inactive one. It could be a nonaggressive tumor that has caused reactive sclerosis. The negative bone scan indicates that the sclerosis is old or is smoldering “at a low flame.” Tumor tissue must still be present, however, due to the relative abundance of protons in water-sensitive MRI sequences. Thus, the findings basically point to a benign tumor. The location within a vertebral body suggests a tumor of notochordal origin. While a “white” vertebral body is always suspicious for malignant lymphoma, the negative bone scan and absence of clinical complaints essentially rule out this diagnosis.

Perfusion disorder?

Old, nonfragmented foci of osteonecrosis may present with osteosclerosis with no shape distortion of the affected bone. This does not explain the relative proton abundance of the lesion in C2, however.

Synopsis and Discussion

The following triad is very specific for a giant notochordal hamartoma as described by Mirra and Brien24:

Negative 18F-FDG PET-CT or negative 99mTc-MDP bone scan

Osteosclerosis in a vertebral body

Absence of T1w signal intensity plus high T2w signal intensity (in the case of moderate sclerosis)

The authors interpret these tumors as notochordal lesions which, unlike the harmless notochordal rests that occur as normal variants, tend to grow until puberty, may occupy an entire vertebral body by their end stage, but then stop growing and do not cause destructive changes like a true chordoma. The two cases observed by the authors were very similar histologically to chordomas but did not meet all the criteria for true chordoma. Thus they were merely followed for a long period of time without showing any radiologic change. Yamaguchi et al.25 refer to this lesion as a benign intraosseous notochordal cell tumor to express its neoplastic nature. This means that these lesions should be closely followed to allow for prompt detection of possible malignant transformation, making them similar in behavior to large enchondromas in large bones. Kyriakos (2011)26 has published a review of benign notochordal lesions. To date we have seen five patients with these lesions and have advised long-term observation (yearly MRI follow-ups), without histologic confirmation. The differential diagnosis should include nonfragmented osteonecrosis, which we have seen with identical radiologic findings—also in a cervical vertebral body—and had histologically confirmed in a patient with a history of pancreatitis. This case explains our wait-and-see approach for a lesion that exhibits the above triad in a vertebral body.

Fig. 3.6 illustrates another case of giant notochordal hamartoma drawn from our files. This lesion was located in the C4 vertebra and was also detected incidentally.

Final Diagnosis

High index of suspicion for a giant notochordal hamartoma in C2. Long-term clinical and radiologic follow-up is recommended.

Comments

When faced with unusual incidental findings, one should be well-prepared enough to consider even an unusual diagnosis.

3.1.4 Case 20 (Fig. 3.7)

Case description

Referring physician: oncologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 47-year-old woman with breast cancer had undergone mastectomy, postoperative radiation to the chest wall, and tamoxifen therapy. Her bone scan showed circumscribed uptake in the C5 spinous process, which was considered suspicious for metastasis. Subsequent MRI upheld this suspicion, and a percutaneous biopsy under CT guidance was recommended. The biopsy was terminated due to severe pain, but CT scans acquired during the procedure cast doubt on the diagnosis of metastasis. A repeat biopsy was still recommended, but the patient refused. The treating oncologist then requested our radiologic consultation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree