3.3 Diseases of Spinal Entheses and Joints

3.3.1 Case 39 (Fig. 3.36)

Case description

Referring physicians: orthopedist and rheumatologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 52-year-old man complained of chest pain radiating to the neck and the left arm, most noticeable in the morning. He did not have typical signs of inflammatory back pain. HLA-B27 was negative and C-reactive protein (CRP) was within normal limits. The thoracic spine was examined by MRI. The radiologist presumed spondyloarthritis and added CT scans, which confirmed his working diagnosis. The patient was referred to a dermatologist to confirm or exclude psoriasis. The dermatologist wrote: “Approximately 2 weeks ago the patient had two coin-sized inflammatory lesions on the lower limbs. The lesions responded to local treatment with betamethasone, and currently the sites show postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. One possible diagnosis is nummular eczema.” The treating orthopedist, like the radiologist, is convinced of a rheumatic systemic disease and requests a definitive diagnosis.

Radiologic Findings

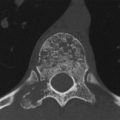

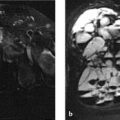

The T2w MR images of the thoracic spine (Fig. 3.36 a, b) show almost homogeneous high signal intensity throughout T7, in the anterosuperior corner of T9, in the upper anterior portions of T10, and under the lower endplate of T11. The T7 vertebra appears sclerotic on CT images (Fig. 3.36 c–e), its lower endplate is destroyed, and its upper endplate shows irregular sclerosis. Parasyndesmophytes are visible in Fig. 3.36 d, e. The anterior portion of the upper endplate of T10 is destroyed and sclerotic (Fig. 3.36 c). CT scans of the thoracic spine also reveal a combined destructive and proliferative process in the left anterosuperior chest wall (Fig. 3.36 f–i).

Location

The changes are reflected in the upper and lower endplates, the vertebral margins and corners, and the anterior chest wall—areas in which numerous entheses occur. Multiple vertebral bodies are involved.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The essential features on CT are a combination of destructive changes and new bone formation or proliferation (sclerosis, parasyndesmophytes). The changes with edema-like signal intensity can be interpreted as an accompanying phenomenon of osteitis, and the whole may be interpreted as a nonbacterial inflammatory process. The similar pathoanatomy of the changes in the anterior chest wall suggests a systemic disease.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

No.

Trauma?

No history, not even for chronic trauma.

Inflammation?

Yes. This is consistent with the pathoanatomic background. Parasyndesmophytes plus simultaneous destructive/proliferative changes in the diskovertebral junctions, and the destructive-proliferative changes in the anterior chest wall, all suggest a psoriatic spondyloarthritis or Reiter syndrome. A bacterial inflammation is not supported by the simultaneous destructive and reparative changes, which are usually metachronous in a bacterial inflammation.

Tumor or metastasis (e.g., from prostate cancer)?

No. The history is negative in this regard and the patient has no known risk factors. In any case the eccentric distribution of the changes in the affected vertebral bodies are not consistent with a neoplastic process. Nor could a tumor explain the parasyndesmophytes.

Regressive (degenerative) process?

No. Sclerosis under the upper and lower endplates would predominate in osteochondrosis, and there would be spondylophytes rather than parasyndesmophytes.

Synopsis and Discussion

The radiologic findings strongly suggest the presence of a psoriasis-associated spondyloarthritis or Reiter syndrome. The latter diagnosis is not supported by the history and clinical data, however (e.g., urethritis, keratoconjunctivitis, etc.). But is psoriasis-associated spondyloarthritis possible if the dermatologist finds no typical signs of psoriasis in the patient (Fig. 3.37, different patient)? Certainly, because the dermatologic examination in this case took place at a time when “coin-sized inflammatory lesions” on the lower leg had already subsided. This is not sufficient to exclude psoriasis, which requires a histologic examination. We ordered a biopsy which confirmed psoriasis vulgaris. Apparently the dermatologist lacked the necessary awareness of the problem at the time of initial presentation; otherwise he would have done an immediate biopsy.

When he presented at our institution, the patient stated in response to specific questioning that some time ago he had pain in the anterior chest wall radiating to the left arm. This fits with the findings in the left manubriocostal region (Fig. 3.36 f–i), which represent asymmetric sternocostoclavicular hyperostosis (SCCH; see also Case 97) and are a common feature of psoriatic spondyloarthritis.

Finally, it should be noted that psoriatic spondyloarthritis belongs to the group of seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

Final Diagnosis

Psoriatic spondyloarthritis with involvement of the anterior chest wall (SCCH).

Comments

The orthopedist, rheumatologist, and radiologist were on the right track clinically and radiologically (following MRI with CT to investigate simultaneous destruction and reactive-reparative proliferation and parasyndesmophytes) but were misled by the inconclusive dermatology report. Insistence upon a histologic evaluation finally yielded a definitive diagnosis, without having to biopsy the spinal lesions or undertake a pointless and invasive search for a primary tumor.

3.3.2 Case 40 (Fig. 3.38)

Case description

Referring physician: general practitioner.

Prior history and clinical question: A 65-year-old woman presented with a long history of nonspecific lumbar pain. Imaging revealed marked sclerotic changes in the lumbar spine, which were interpreted initially as osteosclerotic metastases from an unknown primary tumor. Tuberculous spondylitis was also considered in the differential diagnosis. The family doctor did not believe these diagnoses because the patient appeared clinically well. Before ordering a comprehensive tumor search and biopsy of the sclerotic lesions, the doctor wanted to know if there was a plausible alternative diagnosis for the radiologic changes.

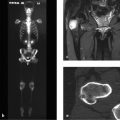

Radiologic Findings

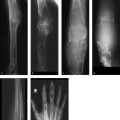

The initial MR images (Fig. 3.38 a, T2w) show areas of markedly increased signal intensity in L3 and L5, which correlate with pronounced sclerotic changes on CT scans (Fig. 3.38 b). The anterosuperior corners of both vertebral bodies are destroyed. Bone spurs project from the inferior edge of the erosions, and both can be characterized as syndesmophytes. These findings were the original basis for the radiology consult. We ordered additional imaging studies as described below.

Location

Based on the CT images in particular, we can definitely relate the destructive (erosive) and proliferative changes to the diskovertebral junctions (at the anterosuperior vertebral margins and upper endplates), which are entheses.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

Bone destruction and new bone formation (syndesmophytes, sclerosis) are apparently taking place simultaneously. The detection of edema-like signal on MRI proves that the process is still florid. This combination of destruction and repair is a typical feature of inflammatory rheumatic enthesitis and is unlike the metachronous destruction and repair that occurs in bacterial inflammations. The edema-like signal in the bone is referable to associated osteitis. Now we need only obtain further clinical information in order to advance our interpretation and move closer to a clinical diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree