3.4 Sacrum

3.4.1 Case 43 (Fig. 3.46)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 12-year-old girl had a 2-week history of nonspecific pain in the right hip, predominantly on the lateral side, which first occurred after a 2½-hour automobile ride followed by a walk around town. Her parents claimed that the girl did not have a visibly strained posture while riding in the car. Regarding sports activities, the girl has participated in school sports, horse riding, and is an avid trampoline jumper. Her history was otherwise unremarkable, and lab tests showed no increase in inflammatory markers. She had no clinical signs of sacroiliitis. Forward bending resulted in a compensatory movement toward the left side with a slight lumbar bulge on the right side. Slight tenderness was noted over the trochanter of the right femur. Based on his clinical findings, the pediatric orthopedist suspected an enthesiopathy in the right hip region (greater trochanter, iliac spines), also noting hamstring shortening on the right side, shortening of the right leg, and limited motion in the lumbar spine. HLA-B27 was positive. Anti-inflammatory therapy was initiated. A diagnosis of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) was considered based on the radiologic findings.

Radiologic Findings

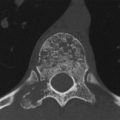

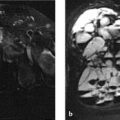

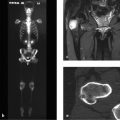

Initial MRI (Fig. 3.46 a) shows a prominent edema-like signal in the right lateral mass of the sacrum. The adjacent sacroiliac joint and ilium appear normal. CT scans (Fig. 3.46 b–h) show an irregular, frayed subchondral contour of the right sacrum. Fusion of the synchondrosis between sacral segments 1 and 2 has not (yet?) occurred, in contrast to the opposite side. Sclerotic changes are visible along the margins of S2 (Fig. 3.46 c, e). Bone spurs are noted at the capsular attachment on the anterior and inferior aspects of the sacroiliac joint on both the sacral and iliac sides (Fig. 3.46 h) and are similar in appearance to traction spondylophytes (arrow in Fig. 3.46 h).

Location

The key radiologic findings are limited to the variant anatomy of the right lateral mass of the sacrum.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The pronounced edema-like signal in the right lateral mass and the sclerotic changes without involvement of the sacroiliac joint, when interpreted within the context of the asymmetric nonfusion of S1 and S2, suggest a mechanically induced reactive process.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

The asymmetric nonfusion (so far) of S1 and S2 on the right side would definitely qualify as a normal variant, similar to many other asymmetric fusions of synchondroses (e.g., ischiopubic) and apophyses in the pelvis.17 Under certain conditions, however, normal variants of this kind may lead to instabilities and may then become symptomatic (see Synopsis and Discussion below).

Trauma?

The girl stated that her favorite sports activities were horse riding and trampoline jumping. These activities constitute repetitive trauma to a growing posterior pelvic ring with an anatomic variant.

Inflammation?

The prominent edema-like signal in the right lateral mass and the erosions in its subchondral contours could be attributed to osteomyelitis—for example, if the adjacent sacroiliac joint were also involved (e.g., effusion). But that is not the case. With such pronounced findings, moreover, we would expect laboratory tests to show an elevated CRP level.

Tumor?

No. An osteoid osteoma would be plausible in a 12-year-old, but there is no CT or MRI evidence of a nidus, see also Case 44. The only other possibility is primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of bone, but then we would expect to find central sclerosis in the right lateral mass.

Synopsis and Discussion

Given the many differential diagnostic possibilities, the present case is a prime example of the challenges that are addressed in this book.

In consultation we decided on a radiologically symptomatic normal variant or a stress-induced failure of fusion of S1 and S2. The following factors support this conclusion:

Asymmetric nonfusion (so far) of S1 and S2 on the right side.

History of high mechanical stresses to the posterior pelvic ring caused by intensive trampoline jumping along with horse riding and school sports. One might ask whether the radiologic findings would have occurred if the girl had engaged only in school sports and riding. In the case of other stress-induced skeletal changes (stress fracture, chronic avulsion trauma, enthesiopathies, etc.), it is known that adding just one stressor to other chronic loads may cause damage to the unconditioned bone or to an attachment between two bones. In our case it is uncertain whether the nonfusion itself was the precipitating factor for the changes or whether the nonfusion resulted from the stress—similar to the chicken-or-egg riddle. Parallels may be drawn with stress fractures of the lower lumbar spine in growing, competitive athletes.

Reactive osseous changes, especially in the S2 segment (sclerosis, bone spurs at the anteroinferior capsular attachment on both the sacral and iliac sides), which indicate that the sacroiliac attachment is unstable. The edema-like signal in the right lateral mass is satisfactorily explained by the unphysiologic loads.

A diagnosis of CRMO, while plausible, is weakened by the absence of effusion or other reactive changes in the adjacent sacroiliac joint and an absence of inflammatory markers in the blood. It should be added that the term “CRMO” (chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis) for nonbacterial autoinflammatory osteitis chiefly affecting the metaphyses of the long bones, mandible, and clavicles is of limited use today. This is particularly true when only one site is involved and further developments are uncertain—that is, it is not known whether a multifocal, recurrent, chronic process will develop in future. Understood in these terms, “CRMO” is actually a misnomer. We propose that the term CRMO be used only if all parts of the acronym are fulfilled.

In our own case material, approximately 30 to 40% of all the cases formerly diagnosed as CRMO are associated with sterile pustular skin changes (pustulosis palmoplantaris, pustular psoriasis, see Case 82 and Case 84. This indicates purely reactive osteitic bone changes, which are often HLA-B27 associated. Today most cases with the formerly used term CRMO have been replaced by the acronym CNO, which stands for chronic nonbacterial osteitis or osteomyelitis. The only factor supporting this diagnosis in the present case would be the positive detection of HLA-B27, but that proves nothing, since 10% of the healthy population is also HLA-B27-positive. This raises the question of whether the patient might have incipient seronegative spondyloarthritis. But this diagnosis is not at all consistent with the absence of clinical and radiologic signs of sacroiliitis.

The nonspecific clinical manifestations in the present case do not have a definite etiologic explanation, though we personally believe that asymmetric findings in the posterior pelvic ring may often be associated with very nonspecific signs including pseudoradicular symptoms. Another consideration is that children often have an atypical pattern of pain projection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree