4.1 Sclerotic Changes

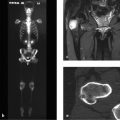

4.1.1 Case 47 (Fig. 4.1)

Case description

Referring physician: rheumatologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 46-year-old woman presented with steroid-sensitive pain in her spine and peripheral joints. She had clinical manifestations of a fibromyalgia syndrome. No functional abnormalities were noted on musculoskeletal physical examination. The pelvic radiograph showed very dense sclerotic areas around the sacroiliac joints and pubic symphysis. These areas were negative on bone scintigraphy. The patient denied having psoriasis or pustulosis palmoplantaris. The test for HLA-B27 gave a negative result.

Radiologic Findings

The pelvic radiograph shows very dense, homogeneous sclerosis on both the iliac and sacral sides and around the pubic symphysis. While the sacroiliac joints have smooth contours and normal width, the symphyseal contours have a slightly ragged appearance. The upper left edge of the symphysis is approximately 4 to 5 mm higher than the right (Fig. 4.1 a). The bone scan shows no pelvic abnormalities (Fig. 4.1 b).

Location

The sclerotic areas are distributed about the articular and synchondrotic junctions.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The sclerotic areas are interpreted as a reactive phenomenon in response to some or other stimulus originating from the sacroiliac joint and the synchondrotic attachment of the pubic bones. The negative bone scan shows that the sclerotic areas are inactive—“the party is over,” so to speak.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes, triangular hyperostoses about the sacroiliac joints, also called hyperostosis triangularis ilii, are a common finding in asymptomatic women of childbearing age.17 Most women with this condition are biparous or multiparous. This also applies to sclerotic areas about the symphysis, especially when associated with hyperostosis triangularis ilii.

Inflammation?

Given the positive answer above, there is no need to pursue the question of inflammation. The fact that the sclerotic areas are negative on bone scans (see Fig. 4.1 b) and were detected incidentally is also inconsistent with inflammation. The normal width of the sacroiliac joint spaces and their smooth contours exclude a reactive inflammatory process such as enthesitis or synchondritis in a setting of spondyloarthritis.

Synopsis and Discussion

The question from the referring rheumatologist implied that spondyloarthritis might be responsible for the sclerotic changes about the sacroiliac joints and symphysis. In particular, he may have considered a pustular arthro-osteitis or enthesio-osteitis, or SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis) syndrome, which are often associated with unusual, nonspecific inflammatory (enthesitic) sclerosis (see Case 39, Case 40, Case 48, Case 49, and Case 97). He had doubts, however, because the patient had neither pustulosis palmoplantaris nor psoriasis, did not have a positive family history, and her HLA-B27 test was negative.

Hyperostosis triangularis ilii (formerly called osteitis condensans ilii) results from transient loosening of the anterior and posterior pelvic ring and symphysis due to pregnancy, but is also found in degenerative diseases of the sacroiliac joints. The increased mobility of the pelvic ring in pregnancy, or the loss of the articular cartilage buffer due to degenerative disease, leads to greater pressure loads and stimulates reactive new bone formation around the anteroinferior corner of the ilium (joint), which marks the pressure center of the sacroiliac joints in standing on both legs. As a result, reactive new bone formation develops around the inferior corner of the ilium, eventually leading to triangular hyperostosis. A similar mechanism is operative at the symphysis pubis, which in the present case shows a step-off that further documents transient loosening of the symphysis.

Final Diagnosis

Reactive sclerosis around the sacroiliac joints (hyperostosis triangularis ilii) and symphysis after pregnancy-related loosening of the pelvic ring, considered an incidental finding and a normal variant.

Comments

When sclerotic skeletal changes are detected incidentally around bony junctions, stress-related hyperostosis should be considered first. Any remaining doubts can be resolved by bone scintigraphy, which will be negative in the case of older stress reactions or normal variants.

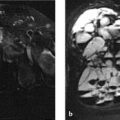

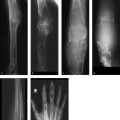

4.1.2 Case 48 (Fig. 4.2)

Case description

Referring physician: orthopedist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 42-year-old woman had a 6-month history of increasing pain in the right hip and upper left thigh. Physical examination showed limitation of motion in the right hip joint. No palpable mass or local warmth was noted in the left thigh. The referring orthopedist stated that no other physical abnormalities were found. Serum inflammatory markers were not elevated. The complaints regressed in response to anti-inflammatory treatment. The orthopedist suspected that the patient had two separate foci of Paget disease.

Radiologic Findings

The radiograph shows massive sclerosis and expansion of proximal portions of the right ilium and left proximal femoral shaft including the metaphysis (Fig. 4.2 a). As the CT images demonstrate, the hyperostotic changes originate from the cortex and/or the periosteum, rather than from the narrowed but still-intact medullary cavities (Fig. 4.2 b–d). Bone scans (not pictured here) showed markedly increased uptake in the suspicious skeletal regions with no other abnormalities. The nuclear medicine physician interpreted these as showing “chronic osteomyelitis,” but bone tumors were also considered.

Location

As noted above, the ossifications originate from the cortex or periosteum, not from the medullary cavity.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

As the bone scan showed, the hyperostotic changes in the right ilium and left femur are active, so this would largely exclude congenital hyperostosis. The most frequent causes of noncongenital hyperostosis are chronic inflammation and primary or secondary bone tumors. It is important to note that the hyperostotic changes do not originate from the medullary cavities but from the cortex and/or the periosteum, also largely excluding a septic bifocal osteomyelitis. This finding also excludes bone tumors such as primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of bone, which generally arise from or involve the medullary cavities (see also Fig. 4.3). Exceptions are periosteal osteoid osteoma and osteosarcoma, but the CT scans do not show a nidus of osteoid osteoma, nor do they show spicules or other features suggestive of periosteal osteosarcoma.

We can also exclude Paget disease because the hyperostotic changes in this case are symptomatic; this would be extremely unusual for Paget disease (see Case 8, Case 9, Case 12, Case 14, Case 51, Case 107, and Case 140). Moreover, the changes in the left femur do not involve the epiphysis, where the structural alterations in Paget disease generally originate in long bones. This leaves us with a bifocal, reactive, chronic proliferative bone process that appears to arise from the periosteum. These characteristics are suspicious for enthesitis.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Inflammation?

Yes, a reactive type. The considerations under Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings would suggest a bifocal enthesitis with proliferative periosteal new bone formation, since current theory interprets the periosteum as an enthesis—that is, a site where soft-tissue structures are attached to bone. These junctions are highly susceptible to systemic reactive inflammatory changes. The areas of cortical thickening on the ilium and femur are also due partly to incipient osteitis.

Tumor?

Very unlikely, aside from a very unusual bifocal form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of bone.

Synopsis and Discussion

Based on the considerations above, the most likely diagnosis is a “rheumatic” enthesitis, which is a type of seronegative spondyloarthritis. Systemic forms of enthesitis associated with exuberant hyperostosis include spondyloarthritis with pustular skin changes (psoriasis and its variant, pustulosis palmoplantaris). After further consultation with the referring orthopedist, we learned that the patient had none of these skin diseases. Of course, this alone does not positively exclude the presence of a skin disease, which would require a dermatologic consult including biopsy of suspicious areas (see Case 39, Case 40, and Case 49). The orthopedist stated that there was no clinical evidence of another form of spondyloarthritis. We recommended that the patient should see a rheumatologist, but unfortunately she has not followed this recommendation as far as we know. An imaging follow-up at 6 months showed no change in the skeletal abnormalities. This makes a neoplastic process very unlikely and does not suggest a pressing need for histologic evaluation. It should be added that hyperostotic changes in spondyloarthritis do not have a specific histology, so a biopsy would have served only to narrow the differential diagnosis.

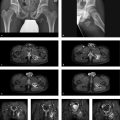

Regarding the differential diagnosis of sclerotic changes in the femur, the case in Fig. 4.3 shows an osteosclerotic osteosarcoma in the femoral neck of an 18-year-old male. Unlike Case 48, the sclerotic process is located in the bone, not in or along the periosteum. The MR images show that the lesion has broken through the bone on the anterior side. The morphology of this case and the patient’s age suggest an immediate diagnosis of osteosarcoma. The only other possible entity would be a primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of bone, and that condition should be histologically confirmed or excluded.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree