4.2 Osteolytic Changes and Changes Associated with Decreased Bone Density

4.2.1 Case 53 (Fig. 4.9)

Case description

Referring physician: trauma surgeon.

Prior history and clinical question: Posttraumatic pelvic radiographs in a 26-year-old woman incidentally revealed a coarse defect in the left iliac wing. Tumor? The patient did not have a prior history of surgery.

Radiologic Findings

The pelvic radiograph shows a large elliptical bone defect with well-defined margins in the left ilium (arrows in Fig. 4.9 a). The iliac crest bridges the defect laterally and superiorly but appears to form a pseudarthrosis at the junction with the solid anterior portions of the ilium. The findings are unchanged on follow-up radiographs obtained at 1 year (Fig. 4.9 b) and 2 years (Fig. 4.9 c). The lesion is classified as Lodwick type IB (punched-out lesion).

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

Any interpretation of the radiographs is somewhat speculative without sectional images. But the fact that the defect remained unchanged in its size, shape, and margins over a 3-year period suggests a congenital anomaly. It is important to know that the bony pelvis, like the calvarium, may have congenital gaps and defects that have no clinical significance and whose etiology is a matter of speculation.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes, very likely. The absence of change over time strongly supports this interpretation.

Inflammation?

No, even a “burned-out” inflammation is excluded by the negative history.

Tumor?

Should at least be considered. A Lodwick type IB lesion in the pelvis could represent a focus of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis, for example. While this type of lesion may be clinically silent, it would show some change over a 3-year period such as an increase or decrease in size, marginal sclerosis, additional foci, etc. As in Case 54, we might also consider vanishing bone disease (Gorham–Stout disease, phantom bone, massive osteolysis, disappearing bone, regional angiomatosis), but the absence of radiologic change would make this diagnosis unlikely as well. The patient is too young for a solitary plasmacytoma, which would also produce clinical manifestations. A simple bone cyst is not supported by the absence of lesion expansion and the lack of marginal sclerosis, which a cyst would surely have developed over a 3-year period.

Necrosis?

Possibly, but the negative history and location suggest otherwise. To the author’s knowledge, avascular necrosis has never been reported in this region. This is because the affected region is not located in a terminal vascular bed.

Synopsis and Discussion

As explained above, the asymptomatic bone defect in the left iliac wing could only be a congenital lesion or an old, burned-out tumor that has taken an atypical course. Aside from simple follow-up radiographs, the patient declined sectional imaging studies and also refused a histologic work-up. The latter decision cannot be faulted, for what would it have accomplished? Remember that this defect has neither a traumatic nor iatrogenic cause. Moreover, the patient had no external scars or focal scleroderma (see Case 11).

Preliminary or Working Diagnosis

Congenital bone defect in the iliac wing.

Comments

A congenital malformation should be considered for an incidentally detected bone defect with no associated periosteal reaction located in the pelvis or skull.

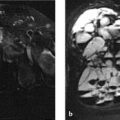

4.2.2 Case 54 (Fig. 4.10)

Case description

Referring physician: rheumatologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 29-year-old woman complained of progressive stabbing and burning pains in the right gluteal region radiating to the right thigh. The symptoms began during a (second) pregnancy about 18 months previously. After the delivery she underwent CT and MRI, which revealed “osteolytic changes and demineralization with cortical defects in the right ilium.” A biopsy showed “corticocancellous bone tissue with chronic scarring and inflammation, consistent with chronic osteomyelitis.” At that point the patient declined further diagnostic studies. Eventually her symptoms worsened until she was unable to walk. The patient stated that she then visited a chiropractor, who gave her an injection and a manual adjustment. She claimed that afterward she was able to walk again. One month before seeing the rheumatologist, she fell onto her buttock and her pain returned. A doctor elsewhere voiced suspicion of a rheumatic disease, and this prompted referral to the rheumatologist. Clinical examination showed no evidence of a rheumatic process. Because the patient was originally from Kazakhstan, the rheumatologist considered tuberculous osteomyelitis with sacroiliitis. He consulted us before ordering another biopsy.

Radiologic Findings

The current pelvic radiograph (Fig. 4.10 a) shows a large defect in the right iliac wing that includes the iliac crest. The defect is surrounded by osteolytic changes with a mixed honeycomb and streaky pattern, which are bordered by a sclerotic zone that is most prominent on the medial side. The symphysis is still widened from the previous pregnancy. The CT scans in Fig. 4.10 b, c, f show subperiosteal and subchondral erosions medial and lateral to the defect. Closer scrutiny of the posterior portions of the ilium in Fig. 4.10 b (magnified view on the right) reveals tortuous, vermiform lucencies in the cancellous bone. Current contrast-enhanced MR images (Fig. 4.10 d, e, g) show patchy hyperintensities in and around the bone.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The key pathoanatomic findings are the large bone defect and the honeycomb lucencies around the defect, which must be interpreted as vascular prints. The destructive changes, therefore, are most likely based on an underlying vascular process.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

No. This is excluded by the clinical presentation and imaging findings.

Trauma?

No. The process was not initiated by trauma, and pregnancy-related loosening of the pelvic ring could not produce structural changes of this kind.

Inflammation?

No. A chronic, septic inflammatory process of this size would include osteolytic changes, sequestra, dense sclerosis, and clinical manifestations of fever, soft-tissue abscess formation, etc.

Tumor or tumorlike lesion?

Yes, probably an angiomatous process that cannot strictly be classified as neoplastic (further details below).

Synopsis and Discussion

As noted above, there is evidence of an angiomatous process that has gradually dissolved the bone. The findings are consistent with vanishing bone disease (Gorham–Stout disease, phantom bone, massive osteolysis, disappearing bone, regional angiomatosis; see also Case 11). This is an extremely rare skeletal disease, difficult to diagnosis histologically, which is characterized by increasing regional resorption of cancellous and cortical bone and their replacement by an aggressively spreading vascular tissue similar to hemangioma or lymphangioma. In recent years the vessels have been identified as mainly lymphatic vessels that may relate to a disturbance of lymphangiogenesis.33 Later the resorbed bone is replaced by vascularized fibrous tissue, at which point a specific histologic diagnosis can no longer be made. The freely proliferating neovascular tissue incites an active hyperemia that probably upsets the normal balance between osteoclasts and osteoblasts causing a predominance of bone resorption, see neurovascular theory in Case 11, section on “Perfusion disorder?”. Today it is known that neither infectious nor malignant or neuropathic factors have causal significance in vanishing bone disease. The main clinical symptom in most patients is a boring pain of gradual onset, as in the present case. Plain radiographs early in the disease show a “patchy osteoporosis” appearing as multiple intramedullary and subcortical lucencies, which in our advanced case are still in direct proximity to the large osteolytic area. Later these foci enlarge and coalesce while new foci appear at the periphery. Then the contours and internal structure of the bone gradually disappear as “demineralization” progresses. The vanished bone areas may reach considerable size, causing grotesque anatomic distortions. Generally the disease is self-limiting and resolves in 1 to 2 years, although some cases may have a fatal termination, especially if complications arise such as chylothorax or severe hemorrhage.13 Further details on this disease are presented in Case 11.

A second biopsy taken from the conspicuous area of soft-tissue changes on MRI, interpreted with the help of a reference pathologist, revealed lymphangiomatosis and confirmed our impression of vanishing bone disease.

Final Diagnosis

Vanishing bone disease (synonyms: Gorham–Stout disease, phantom bone, massive osteolysis, disappearing bone, regional angiomatosis) in the right iliac wing.

Comments

Vanishing bone disease is a rare entity that should be considered in younger patients with large, painful osteolytic defects and no associated osteoblastic or periosteal reaction.

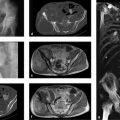

4.2.3 Case 55 (Fig. 4.11)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 24-year-old professional soccer player underwent MRI of the pelvis for investigation of pubalgia. The images incidentally revealed a hyperintense (water-equivalent) lesion in the right iliac wing (Fig. 4.11 a). Pelvic stability was investigated further by CT (Fig. 4.11 b–g), which showed attenuation values of 10 to 20 HU in the lesion. The patient had no prior history of major trauma and no prolonged episodes of pain in the right iliac wing.

Radiologic Findings

The CT correlate of the MRI finding is an expansile osteolytic lesion with no internal structural features and a solid bony cap over its medial and lateral portions. Linear lucencies, interpreted as vascular channels, radiate from the upper and lower ends of the lesion into the intact cancellous bone (Fig. 4.11 e, g).

Location

The expansile osteolytic lesion is located in a region of the iliac wing that is very thin. It is related superiorly and inferiorly to two large vessels.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The MRI and CT findings indicate a cystic process rather than a solid lesion.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Not previously described at this location, although this interpretation would be consistent with the negative history and lack of clinical manifestations.

Trauma?

Yes, in principle, especially in a professional soccer player who is constantly subject to jolts, falls, kicks, etc. that could have caused intraosseous bleeding.

Tumor or tumorlike lesion?

We might consider a unilocular juvenile bone cyst at an unusual location (only about 2% of all juvenile bone cysts are located in the pelvis).

Synopsis and Discussion

The lesion in the right iliac wing can certainly be interpreted as cystic. But imaging can definitely classify the lesion as a juvenile or unilocular bone cyst only if contrast-enhanced MRI can show an enhancing cyst wall (membrane composed of loose, vascularized fibrous tissue (see Case 132, and Fig. 7.25 in Case 143) and if the interior of the lesion does not show significant enhancement during the usual examination time. This study was not done in the present case, nor is it strictly necessary, since the lesion is an asymptomatic incidental finding. Given the vascular channels noted at the superior and inferior poles of the lesion, the cyst may well have developed at one time as an asymptomatic sequel to a traumatic intraosseous hemorrhage, since the ilium at the lesion site is very thin. Ultimately we cannot say if the lesion should be classified as a posttraumatic intraosseous cyst or as a juvenile bone cyst that has not yet resolved.

As noted above, a unilocular (juvenile) bone cyst in the pelvis is rare. A bone cyst at that location is more common in older patients, which is not surprising when we consider that the lesion in the present case was a purely incidental finding. Juvenile bone cysts are typically located in the long tubular bones (ca. 81% in the humerus and femur). They become symptomatic only when disrupted due to trauma. On MRI the associated intracystic hemorrhage may produce a fluid level within the otherwise clear intralesional fluid, though it would occupy an uninterrupted area (see Fig. 7.25) and would not form multiple levels as in an aneurysmal bone cyst.

A histologic examination or even prophylactic dissection would be unnecessary in our case if the patient remains free of complaints.

Fig. 4.12 illustrates the case of a 41-year-old man with a focus of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis or eosinophilic granuloma in the right lower ilium. The patient had an approximately 6-month history of pain in that area, which was initially interpreted as “sciatica-like” and treated with anti-inflammatory drugs. The lesion had a “geographic” shape on CT scans (Fig. 4.12 a–c) with a small central “sequestrum.” This prompted us to classify the lesion as a typical eosinophilic granuloma or focus of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis (see also Case 9 and Case 24. Unfortunately, MRI was also performed (Fig. 4.12 d) and water-sensitive sequences showed significant edema-like signal which caused us to question our diagnosis of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. The edema-like signal also suggested an osteoblastoma. A CT-guided percutaneous biopsy finally confirmed a focus of Langerhans-cell histiocytosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree