4.6 Hip Region

4.6.1 Case 67 (Fig. 4.32)

Case description

Referring physician: rheumatologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 31-year-old woman complained of pain in the metacarpophalangeal joints, knees, and hips. She had been diagnosed 11 years earlier with status post-Perthes disease and treated surgically, but no further information was available on this condition. She gave no history of health problems in childhood or puberty. The metacarpophalangeal joint pain raised suspicion of hemochromatosis, but the referring rheumatologist excluded that disease based on normal iron metabolism markers and genetic testing. Rheumatoid serology and inflammatory markers were normal.

Radiologic Findings

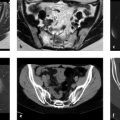

The femoral heads appear flattened and the femoral necks shortened. Due to the flattened shape of the femoral heads, the acetabula are relatively shallow and do not form a normal, medially convex curve (Fig. 4.32 a). The joint spaces show central narrowing on both sides. An osteophyte is noted on the right femoral head, and the left femoral head shows subchondral, cystlike lucencies. The heads of the metacarpals (Fig. 4.32 b) are consistently flattened, similar to the femoral heads. Sclerotic foci and small rounded lucencies are noted, especially in the second and third metacarpals of the right hand. The metacarpophalangeal joint spaces are of normal width, and the opposing joint contours of the proximal phalanges appear normal. All other articular structures, including the carpal joints, also appear normal.

Location

The pathologic findings are concentrated on the epiphyses.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The flattening and structural irregularities of the femoral and metacarpal heads suggest a congenital growth disturbance of the epiphyses.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes. This is supported by the multiple sites of occurrence of anatomically deformed epiphyses (epiphyseal dysplasia).

Perfusion defect with necrosis?

This question is appropriate with regard to the hip joints. But if we place the hip and metacarpal deformities under one heading (osteonecrosis), as it is tempting to do, it would be difficult to imagine multiple osteonecrotic foci in all the metacarpal heads.

Synopsis and Discussion

In retrospect, the diagnosis of status post-Perthes disease made 10 years ago at a different institution is not reasonable because it is not consistent with the radiologic findings in the metatarsal heads 10 years later. The late sequelae of avascular necrosis of the femoral heads in childhood may have imaging features similar to epiphyseal dysplasia (flattened heads, shallow acetabula, subchondral structural changes), but generally the clinical history would show evidence of long-term pain. Moreover, Perthes disease is very rare in girls.

Viewed in themselves, the deformities of the metatarsal heads might well be attributed to hemochromatosis (see Fig. 7.45 d in Case 155). But the following arguments do not support hemochromatosis as the cause of the metacarpophalangeal joint changes, quite apart from the genetic and laboratory test results:

The disease occurs very rarely in females.

There are no cartilage calcifications to indicate secondary chondrocalcinosis.

The carpal joints are not involved.

There are no anatomic changes in the bases of the phalanges that oppose the deformed metacarpal heads. This proves that the deformities are not based on a disease arising from the joint.

Thus, a synoptic review of all the findings definitely points to a systemic epiphyseal dysplasia (known also as multiple epiphyseal dysplasia or Fairbank disease), a skeletal disease with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance. It is a genetically heterogeneous dysplasia based on a nonallelic mutation. Its clinical presentation is variable but is relatively constant within families. It most commonly affects the epiphyses of the hip, knee, ankle, and shoulder joints. Typical clinical signs are as follows37:

Prominent, usually painful joints with limited mobility, a waddling gait

Normal or moderately short stature with normal body proportions

Frequent pronounced thoracic kyphosis, back pain

Classic radiologic signs are as follows:

Irregularities of the epiphyses and later in the joint contours of tubular bones (hips, knees, ankles, hands, and feet). In middle and late childhood the epiphyses become flat (Ribbing type) or small (Fairbank type).

Variable flattening of vertebral bodies and irregular endplates, especially in the thoracic spine

Normal metaphyses with minimal shortening of tubular bones

The disease is usually manifested after 2 years of age but occasionally goes unnoticed until early adulthood. Common differential diagnoses are hypoparathyroidism, pseudoachondroplasia, and (in the hip joint) Perthes disease.

Our case, while not classic, is nevertheless clear-cut. The anomalies represent a very potent preosteoarthritic condition.

Final Diagnosis

Epiphyseal dysplasia of the metacarpal and femoral heads with secondary acetabular dysplasia—not prior avascular necrosis of the femoral heads. (Synonyms for epiphyseal dysplasia: multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, Fairbank disease, Ribbing disease, dysostosis epiphysealis multiplex.)

Comments

Besides prior avascular necrosis (Perthes disease), the differential diagnosis of deformed femoral heads and acetabula should include dysplasias, which can be confirmed or excluded by imaging additional joints (e.g., hands, knees).

4.6.2 Case 68 (Fig. 4.33)

Case description

Referring physicians: orthopedist and radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 48-year-old man complained of occasional left hip pain after jogging. Maximum passive flexion and internal rotation did not reproduce the pain. The orthopedist asked about a possible bone tumor (biopsy: yes or no?), and the radiologist requested interpretation of the sectional imaging findings in the left hip (normal variant?).

Radiologic Findings

CT images (Fig. 4.33 d, e) show a circumscribed osteolytic lesion with marginal sclerosis at the anterior femoral head–neck junction. It correlates on MRI with a slightly inhomogeneous, hyperintense figure (Fig. 4.33 a–c). There is also a mild associated hip effusion. The offset between the femoral head and femoral neck is absent, that is, the anterior contour of the femoral neck is not posteriorly convex at the head–neck junction. Thus we do not see the usual tapering of the femoral neck relative to the head.

Location

The radiologic findings are located precisely where the joint capsule is closely apposed to the bone, and also where the distance between the acetabular margin and femoral neck is shortest at high degrees of flexion and internal rotation. This area is also called the “vulnerable zone.”

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

Given the location of the finding, it is not difficult to characterize it as stress-induced—for example, circumscribed bone resorption based on mucoid degeneration of the subchondral bone.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

This question is justified because this type of finding, called a herniation pit (where synovial and cartilage tissue herniate into the bone), is often noted incidentally on pelvic radiographs. Histologically the pit contains connective tissue with loose myxoid, necrotic bone, cartilage, and fluid. This is definitely pathologic, of course, but when such a finding is detected incidentally, in many healthy individuals it can also be correctly classified as a normal variant. It should be added that histology has apparently been investigated only in symptomatic hips. On the other hand, a herniation pit is very often found in cam-type hip impingement; some authors attribute this to constant impingement of the convex-shaped femoral neck against the acetabular rim. Reportedly this also causes frictional wear and/or avulsion of the acetabular cartilage and/or labrum. In the present case, the complete MRI series (not pictured here) showed no pathologic changes in the labrum. A recent study38 found no relationship between the presence of a herniation pit and femoroacetabular impingement. It is likely that only long-term results over a period of 10 to 20 years would show whether a herniation pit with or without hip impingement is an early indicator of later osteoarthritis.

Trauma?

As a chronic stress-related phenomenon, yes.

Tumor?

No. This answer follows from the discussion under Normal variant or malformation above.

Regressive change?

Yes, if an intraosseous ganglion is considered as a stress-induced regressive change.

Synopsis and Discussion

Given the lack of clinical symptoms, the finding in the proximal anterolateral quadrant of the femoral neck can be classified as a herniation pit.

Fig. 4.34 a–c shows radiographs and CT of a herniation pit (arrows in Fig. 4.34 a) in a different patient. Again, the radiolucency with marginal sclerosis was noted as an incidental finding.

Final Diagnosis

Herniation pit, which probably did not cause the patient’s complaints.

Comments

Herniation pits may be observed as an incidental finding and normal variant or in association with cam-type hip impingement. The latter is proven clinically by forcible flexion and internal rotation.

4.6.3 Case 69 (Fig. 4.35)

Case description

Referring physician: pathologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 53-year-old man had a 1-year history of right hip pain, most noticeable after prolonged exercise and while sitting. On clinical examination, a stabbing pain was elicited by strong passive flexion and internal rotation of the hip. MRI revealed a tear in the acetabular labrum (Fig. 4.35 a, c). The orthopedist confirmed the labral tear arthroscopically and took a sample from the proximal anterior femoral neck (specifically, the anterosuperior quadrant of the femoral neck) because he could not confidently classify the finding at that location by radiography or MRI. He suspected an enchondroma. The pathologist found a pleomorphic fibro-osseous lesion (connective tissue with loose myxoid, small lymphocytic inflammatory foci, and necrotic bone), which he could not positively identify. He was not satisfied to report “no evidence of malignancy” and requested a consult.

Radiologic Findings

The T2w MR images show a multicentric lesion of inhomogeneous signal intensity in the anterior (anterosuperior) femoral neck. Fine hyperintensities are visible among irregular signal voids. The anterior labrum is torn, and a joint effusion is present. The femoral neck bulges anteriorly, eliminating the usual offset between the femoral head and neck. The radiographs (arrows in Fig. 4.35 d, e) show multicentric lucencies in the anterolateral femoral neck, that is, in the “vulnerable zone” (see Case 68).

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The location of the lesion makes it easy to classify as a stress-induced, reactive phenomenon. This interpretation is supported by its multicentric structure.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

The combined presence of the labral tear and femoral neck lesion is suggestive of hip impingement with a herniation pit, especially since the anatomy of the femoral neck predisposes to that condition.

Inflammation?

The lymphocytic inflammation described by the pathologist is purely reactive, and the overall finding does not result from osteomyelitis, for example. An inflammatory process would also produce different clinical findings.

Tumor?

No. What kind of tumor would occupy an eccentric location on the femoral neck margin? An eccentric chondroma, see Case 70? If the multiple lucencies on the radiograph were interpreted as cartilage lobules, they would show markedly increased signal intensity on MRI. But this is not the case. The multicentric pattern on MRI is also inconsistent with chondromyxoid fibroma.

Regressive change?

See under Case 68.

Synopsis and Discussion

In contrast to Case 68, the herniation pit is symptomatic and apparently results from cam-type hip impingement.

Final Diagnosis

Multicentric herniation pit of the right femoral neck, most likely occurring within the context of hip impingement and a labral tear.

Comments

When a labral tear is confirmed radiologically and arthroscopically in a cam-type hip impingement syndrome, an osteolytic lesion in the “vulnerable zone” probably represents a symptomatic herniation pit.

4.6.4 Case 70 (Fig. 4.36)

Case description

Referring physicians: orthopedist and radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: An 11-year-old boy presented with right hip pain and could walk only on crutches. He responded well to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. The orthopedist thought that the radiograph indicated a cyst. The radiologist believed it was a solid tumor.

Radiologic Findings

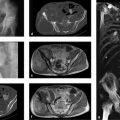

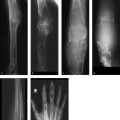

The radiographs show an eccentric osteolytic lesion with a partially sclerotic margin located in the medial portion of the right femoral head (Fig. 4.36 a, b) corresponding to a Lodwick Grade I C osteolytic lesion (the medial cortex is disrupted, and the margin with the epiphyseal plate is poorly defined and probably disrupted). MRI, especially the T1w images, shows a definite absence of medial cortex on the femoral head. The lesion shows marked contrast enhancement (Fig. 4.36 e, f), and Fig. 4.36 f shows penetration to the epiphyseal plate. The lesion contains small “cystic” cavities with fluid levels (Fig. 4.36 g, h), and joint effusion is present. The water-sensitive sequences (Fig. 4.36 d, g–i) and contrast-enhanced images show markedly increased, edema-like signal intensity in both the femoral head and neck.

Location

The lesion has its epicenter in the proximal femoral epiphysis.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The findings indicate a solid tumor (contrast enhancement!) that has invaded the joint and epiphyseal plate from the femoral head and is associated with significant edema in the adjacent bone. The joint effusion most likely results from tumor ingrowth into the joint but may also represent a “sympathetic” effusion, or both. The small cavities within the lesion may be circumscribed hemorrhagic areas with fluid levels, that is, secondary aneurysmal bone cysts.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Inflammation?

No clinical manifestations. Also, we would expect to find reactive sclerosis around the lesion.

Tumor?

Yes, one whose epicenter is the capital femoral epiphysis and is associated with edema and joint effusion. It contains small cavities with fluid levels consistent with secondary aneurysmal bone cysts, as described above.

Avascular necrosis?

No, primary avascular necrosis of the femoral head would be associated with signs of fragmentation.

Synopsis and Discussion

Given the age of the patient, the site of occurrence, and the morphology of the osteolysis, there is a high probability that the lesion is a chondroblastoma. The lesion and its location have all the essential elements of chondroblastoma:

More than 80% of cases occur in the second decade of life.

The femoral head, with 9% of cases, is the fourth most common site of occurrence after the humeral head (ca. 17%) and the epiphyses of the knee (34%).

In 50% of cases the tumor occurs in both the epiphysis and the metaphysis (as in our case). In approximately 45% of cases it is confined to the epiphysis or apophysis, but is always close to the growth plate. Only about 5% of tumors occur in the metaphysis. Approximately 75% of chondroblastomas have an eccentric location in the epiphysis.

The cortex is involved in around 80% of cases.

In approximately 60% of cases the interior of the tumor shows trabeculation and/or matrix calcification. We cannot confirm the latter in our case because CT scans were not obtained.

Secondary aneurysmal bone cysts occur in a full one-fifth of cases.

The majority of cases investigated to date by MRI have shown marked perifocal edema (along with synovitis), attributed in part to the high prostaglandin level in the tumor. Today, perifocal edema provides a highly reliable differentiating criterion from epiphyseal enchondroma (rare, see below) and giant cell tumor. Most chondroblastomas have a rich vascular supply.

The radiologic diagnosis was confirmed histologically.

Fig. 4.37 a–h illustrates the case of a 10-year-old boy with a metaphyseal enchondroma in the right proximal femur (see arrows in Fig. 4.37 a). The lobular arrangement of the lesion is subtly displayed in the MR images in Fig. 4.37 b, c (T2w) and Fig. 4.37 d (contrast-enhanced). No perifocal edema was found. Our differential diagnosis included chondromyxoid fibroma, a herniation pit at an atypical site (too far medially), and finally eosinophilic granuloma. Because the boy was symptomatic, a biopsy was performed. We were surprised by the diagnosis of enchondroma.

Final Diagnosis

Chondroblastoma in the right proximal femoral epiphysis.

Comments

A well-perfused osteolytic lesion in an epiphysis with marked perifocal edema in a young patient is strongly suspicious for chondroblastoma.

4.6.5 Case 71 (Fig. 4.38)

Case description

Referring physician: orthopedist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 42-year-old woman had a 2-year history of increasing right hip pain. She was otherwise healthy and showed no abnormalities on physical examination. A subsequent pelvic radiograph (Fig. 4.38 a) displayed multiple “cysts” in the femoral head and neck and in the acetabulum. The hip joint space was narrowed relative to the left side. Unusual presentation of hip osteoarthritis or a tumor?

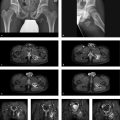

Radiologic Findings

The pelvic radiograph shows multicentric lucencies in the acetabulum, femoral head, and proximal femoral neck with narrowing of the joint space (Fig. 4.38 a). Corresponding MR images (Fig. 4.38 b, c) demonstrate a well-perfused synovial process with a nodular structure. The CT scans in Fig. 4.38 d, e clearly display the deep defects in both articulating bones. Calcifications are not visible within the defects or holes.

Location

Intra-articular focus with spread to the articulating bones.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The findings indicate an active, proliferative, nodular or villous synovial process that is destroying the adjacent bony structures. The concomitant destruction of articular cartilage has led to joint space narrowing.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Inflammation?

Possibly, since any chronic inflammatory synovial process can first erode and then destroy the adjacent bone.

Tumor?

Yes in principle, for even tumors that spread along the surface of the synovial membrane (e.g., hemangioma, primary synovial sarcoma) or tumorlike lesions (osteochondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis [PVNS]) can destroy the adjacent bone.

Synopsis and Discussion

As noted above, the differential diagnosis is broad, ranging from an inflammatory or granulomatous synovial process to a malignant tumor of the synovial membrane:

We may be dealing with an inflammatory rheumatoid process. Gout may produce changes similar to those in our case, except that the bone defects arise mostly from medullary tophi and not from inflamed synovium (see Case 136). Rheumatoid arthritis would involve multiple joints, especially in the hands and feet, and would produce bilateral changes. The same applies to a very rare granulomatous articular process, namely multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (see Case 123). Our patient had complaints only in her right hip, however.

Hemangioma or a posttraumatic vascular malformation can produce the same radiologic features as in our case, but generally they are associated with severe and recurrent hemarthrosis. In the case of an arteriovenous malformation, we know from experience that the larger vessels are directly visualized in postcontrast CT or MRI; this did not occur in our case.

If osteochondromatosis were present, T2w MRI would show intra-articular loose bodies with high signal intensity in the thickened synovial membrane, while CT might show calcified chondromatous bodies.

The most likely diagnosis is PVNS for the following reasons:

The relatively long history is consistent with PVNS.

The process is solitary.

The radiograph and sectional images show large cystlike lucencies in the cancellous bone with destruction of the subchondral plate in both articulating bones. The sectional images clearly show that the destructive process originates from the synovial membrane. An “apple-core sign” is often present in the femoral head and neck (see Case 72) though it is absent in our case. Fine linear and focal hypointensities in the proliferative synovial process caused by iron deposition from recurrent intrasynovial hemorrhages are not clearly visible in the images reproduced here (for technical reasons) but can be seen in the originals. There is no periarticular osteoporosis like that which may occur in bacterial or rheumatoid arthritis.

The cartilage destruction and the cartilage-damaging effect of iron deposits have led to degenerative changes with joint space narrowing.

The diagnosis of PVNS is very likely but still requires histologic confirmation, as in the present case. PVNS is a chronic, generally monoarticular joint disease characterized by heavy villous formation and synovial proliferation, which is usually destructive to adjacent bone. Histology reveals severe, villous histiocytic and vascular proliferation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree