6.1 Upper Arm

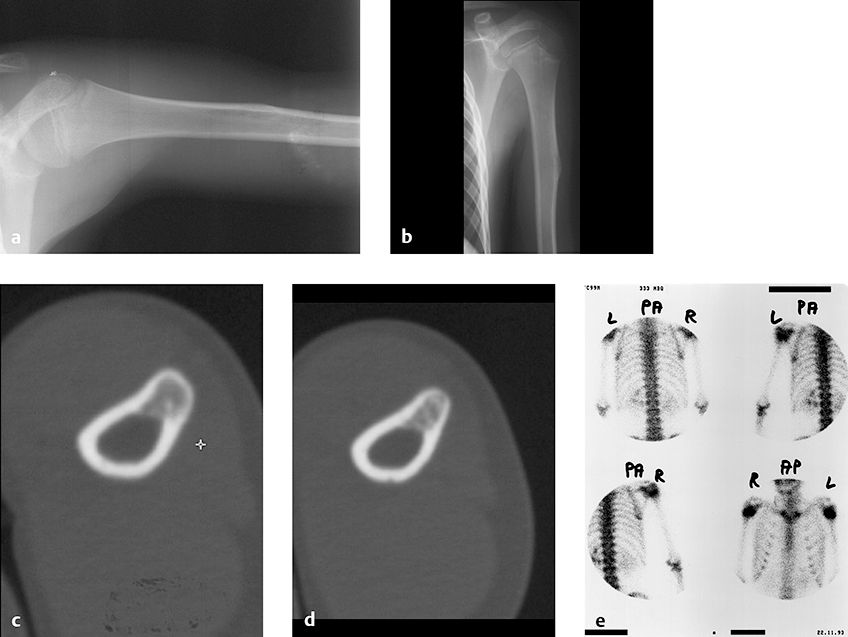

6.1.1 Case 99 (Fig. 6.1)

Case description

Referring physician: radiologist.

Prior history and clinical question: When examined during a regular checkup 1 year earlier, a 7-year-old boy had been diagnosed with a “functional abnormality” of the right thumb that was not further specified. In a subsequent preschool examination, the boy had difficulty in fully extending his right knee. His mental and physical development was normal, and he had a negative family history. Radiographs were obtained and the radiologist offered a tentative diagnosis of melorheostosis.

Radiologic Findings

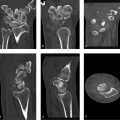

The radiograph of the right hand (Fig. 6.1 c) shows dense linear and columnar ossifications in the first, second, fourth and fifth metacarpals, also in the proximal phalanges of those fingers, the distal phalanges of the first and fifth fingers, and the middle phalanx of the fifth finger. Incipient sclerosis is noted in the middle phalanges of the third and fourth fingers. Focal opacities are visible in all the carpal bones and in the radial epiphysis. The thumb appears slightly too short. Very dense bands and foci of sclerosis are also noted in the right scapula, throughout the humerus, and in the radius and ulna (Fig. 6.1 a, b). Other areas of abnormal endosteal sclerosis are present in the epiphysis of the right femoral head, on the medial side of the right proximal femoral diaphysis (Fig. 6.1 d), in the right tibial shaft (Fig. 6.1 e), and in the talus of the right foot, which shows a more clumplike pattern of sclerosis (Fig. 6.1 f).

Location

The areas of abnormal sclerosis are endosteal and occur only on the right side (images of the contralateral side are not pictured here). Their distribution, therefore, is unilateral and segmental.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The unilateral segmental distribution of the sclerotic areas, some showing an ivory density, and the age of the patient are suggestive of bone dysplasia with too much bone.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

Yes. The findings are typical of melorheostosis affecting the limb bones on the right side of the body.

Inflammation?

No history. Reactive inflammatory bone formation is rarely as solid and well circumscribed as in this case. We do not know of an inflammatory bone process that would have a segmental distribution limited to one side of the body.

Tumor?

Multifocal osteosarcomas do occur, but not in a unilateral distribution as in this case.

Synopsis and Discussion

The endosteal, melorheostotic new bone formation can be described morphologically as showing a mixed striate, osteoma-like (osteopathia striata–like) pattern combined with a “flowing candle wax” appearance. There is no other reasonable differential diagnosis. Further information on melorheostosis can be found in Case 17 and Case 88. We attribute the child’s clinical complaints to fibrotic soft-tissue changes in the thumb and about the knee, which occur in approximately 60% of patients with melorheostosis (see also Case 88). These fibrotic changes may eventually ossify (see Fig. 6.3 below) and, when viewed in isolation, can mimic myositis ossificans (Fig. 6.3 a).

Fig. 6.2 shows an unusual case of bilateral involvement by melorheostosis with clear-cut radiographic features in a 10-year-old boy with brachydactyly of the thumbs and index fingers. The ossifications are more pronounced on the radial side as they follow the distribution of “sclerotomes,” or skeletal zones supplied by individual sensory spinal fibers. We attribute the brachydactyly to associated soft-tissue changes in the affected phalanges leading to growth disturbance.

Fig. 6.3 illustrates the case of a 36-year-old man with pronounced melorheostosis of the right upper limb, again presenting unmistakable radiomorphologic features (“candle wax” pattern on the distal humerus, radius, and bones of the hand). Note the ossification in the right axilla. Marked subcutaneous fibrotic changes, associated with considerable pain, were found on the right forearm and the ulnar side of the hand. The symptoms had begun in puberty, and the patient eventually lost the use of his right arm. Note the segmental distribution of the changes on the ulnar side, again following the sclerotomes as in the previous case (Fig. 6.2).

Final Diagnosis

Melorheostosis.

Comments

A segmental arrangement of solid ossifications in the upper and/or lower limb distributed along sclerotomes always indicates melorheostosis. Since the disease may be complicated by soft-tissue changes, it should not be dismissed as a harmless normal variant.

6.1.2 Case 100 (Fig. 6.4)

Case description

Referring physician: pediatrician.

Prior history and clinical question: An 18-year-old male had a complex condition that included epilepsy, dementia, muscular dystrophy, nephrocalcinosis type 1, etc. He had been on anticonvulsant medication (sodium valproate) for a number of years. Because the patient developed severe osteoporosis with an osteomalacic component (resulting from the muscular dystrophy and anticonvulsant therapy) with repeated bone fractures, treatment with cholecalciferol was tried but was unsuccessful. Bisphosphonates were started 2 years previously in an effort to treat the osseous changes. Follow-up radiographs of the upper and lower limbs showed a surprising finding, which was referred to us for investigation.

Radiologic Findings

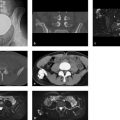

Current radiographs of the upper and lower limbs taken in 2004 (Fig. 6.4 b, c, e) initially show a very severe narrowing and developmental disturbance of the imaged long bones (epiphyseal plates still open in an 18-year-old!) with severe bowing of the bones about the right knee joint. Dense sclerotic changes are visible in the metaphyses. A radiograph of the right arm in 2002 (Fig. 6.4 a; a prior radiograph of the left side does not exist) shows varus bowing caused by an old malunited fracture at the junction of the middle and upper thirds of the diaphysis; there is no metaphyseal sclerosis. A radiograph of the right knee in 2002 (Fig. 6.4 d) shows a fracture of the femoral metaphysis that healed with gross deformity and excessive callus formation, but without sclerotic changes.

Location

The unusual opacities on the 2004 radiographs are confined to the metaphyses.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The unusual zones of metaphyseal sclerosis are acquired, as they did not exist 2 years earlier. They represent new bone.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

The metaphyseal opacities apparently result from the bisphosphonate therapy initiated 2 years earlier. The patient’s overall condition and medication did not change during that period. Given this plausible chain of causality, we do not need to consider the usual range of basic entities.

Synopsis and Discussion

This young man has a complex skeletal disorder that may be described as a severe developmental abnormality characterized by significant osteoporosis with an osteomalacic component. It results from a lifetime of muscular dystrophy and chronic anticonvulsant drug therapy, which is known to cause osteomalacia in some patients.

Bisphosphonates inhibit the osteoclastic breakdown of bone, leading to decreased bone resorption. This effect appears first in the metaphyses because they directly adjoin the growth plate, whose metaphyseal side consists of the “zone of provisional (or preparatory) calcification.” When resorption in this zone is absent or greatly diminished, the result is dense bone formation similar to that in marble bone disease. Intermittent bisphosphonate therapy in a growing skeleton may give rise to thin, sclerotic metaphyseal bands in the long tubular bones. The bands are directed parallel to the growth plates, with each line representing one treatment cycle. Only their extreme radiographic density distinguishes these bands from metaphyseal growth lines (Harris lines), which result from episodic growth (as a normal variant or growth disturbance) and resemble the growth rings of a tree.

Long-term bisphosphonate therapy, as in the present case, may induce the development of broader and denser bands. Dense bands (Fig. 6.4 c) may also appear around the apophyses and around small round and irregular bones (carpals, tarsals), whose actual growth zone is located between the ossification center and articular cartilage (synonyms: acrophysis, spherical growth plate). “Growth rings” may also develop in the vertebral bodies due to bisphosphonate therapy and create a “bone in bone” pattern like that seen in marble bone disease.

Final Diagnosis

Dense metaphyseal bands induced by bisphosphonate therapy.

Comments

Bisphosphonate therapy in the growing skeleton may induce unusual zones of metaphyseal sclerosis that result from the inhibition of osteoclastic and osteocytic bone resorption.

6.1.3 Case 101 (Fig. 6.5)

Case description

Referring physician: orthopedist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 57-year-old woman presented with a long history of left shoulder pain. She stated that the pain would worsen from time to time, becoming intolerable. She claimed good response to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. MRI raised suspicion of a neoplastic process. Otherwise the patient was in good health.

Radiologic Findings

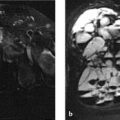

The coronal STIR image in Fig. 6.5 a shows a large area of edema-like signal occupying the left humeral head and proximal metaphysis. The axial T1-weighted (T1w) image in Fig. 6.5 b shows an elliptical signal void bordering the posterior circumference of the humeral head, just behind the greater tuberosity. The lesion has a peripheral rim of intermediate signal intensity, creating a target pattern.

Location

The possible cause of the edema-like signal is located in the bone (Fig. 6.5 b) but lies directly beneath the infraspinatus tendon and a possible bursa.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The two principal findings on MRI are a large area of edema-like signal and a signal void located behind the greater tuberosity. It is logical to assume that both findings are related. The low signal intensity of the focal lesion suggests that it is osseous or has a low proton density. We ordered CT scans as a simple, straightforward way to resolve these questions. CT definitely shows a calcific process within a bone defect (Fig. 6.5 c, d). Between the rim of the osteolytic defect and the calcific lesion is a transitional zone whose intermediate signal intensity suggests synovial tissue or a kind of capsule, but may also represent uncalcified osteoid, for example. Thus, the findings may indicate a tumor with pronounced perifocal edema such as osteoid osteoma, an enthesitic process that has eroded into the bone, or even a primary inflammatory process.

Assignment to a Possible Basic Entity

Normal variant or malformation?

No, the clinical presentation alone indicates a significant disease process.

Trauma?

The patient did not give a history of acute trauma. On the other hand, the principal finding is located below a region that is subject to constant, significant stress, namely an enthesis.

Inflammation?

The edema-like signal may be interpreted as a reactive inflammatory process or osteitis. The lesion just behind the humeral head could be a sequestrum.

Tumor?

Quite possibly, an osteoid osteoma with a calcified nidus and marked perifocal edema.

Synopsis and Discussion

The above considerations give us the following differential diagnosis:

Osteomyelitis with a sequestrum

Osteoid osteoma

Calcified tendinitis and/or bursitis that has eroded into the bone

On differential diagnosis 1

This diagnosis is not consistent with the history. With bacterial osteomyelitis, the patient would have had a shorter history, fever, and other signs. She had no risk factors for osteomyelitis such as diabetes mellitus.

On differential diagnosis 2

This diagnosis is not supported by the patient’s age or history. Osteoid osteoma would most likely be characterized by constant pain and a shorter history.

On differential diagnosis 3

This diagnosis is supported by the following findings:

Location: The location is typical of a calcifying tendinitis or bursitis periodically eroding into the bone. The calcified material in the bone is resorbed after these acute episodes, and any extraosseous calcification at the perforation site has disappeared. The shoulder with its numerous entheses (tendons and capsular attachments) is a musculoskeletal weak point that is subjected to constant heavy loads.

Age of the patient: Calcifying tendinitis or bursitis typically occurs in older individuals.

History: The history consists of several years of intermittent shoulder pain with periodic exacerbations. During the exacerbations, a nonspecific, highly inflammatory process develops in the tendon attachment or bursa leading to resorption of the adjacent bone and eventual breakthrough (of the calcifications) into the bone.

Fig. 6.6 shows an almost identical case in a 67-year-old man with calcifying tendinitis or bursitis eroding into the bone. He was seen 2 weeks after experiencing an acute, stabbing pain in his left shoulder lasting approximately 48 hours. The radiograph (arrows in Fig. 6.6 a) showed an osteolytic area in the region of the greater tuberosity. The bone scan (Fig. 6.6 b) showed focal increased uptake, and MRI (Fig. 6.6 c) showed marked edema-like signal intensity around a hypointense focus, which CT (Fig. 6.6 d, e) identified as a calcified mass. The scan in Fig. 6.6 d clearly documents the pathogenesis of the process: An extraosseous calcified mass relating to the calcified tendon or bursa is continuous with an intraosseous calcified mass through a defect in the cortex.

Another case of cortical erosion by calcifying tendinitis or bursitis is illustrated in Fig. 6.7. The patient, a 57-year-old woman, had hyperacute pain symptoms several days before MRI. Her right shoulder was swollen and warm to the touch, mimicking arthritis. The MR images (Fig. 6.7 a–g) are self-explanatory. A radiograph (Fig. 6.7 h) at the time of MRI showed an osteolytic area in the greater tuberosity, in which ground-glass opacities could be seen. After 3 months of intensive therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, her clinical symptoms resolved completely and a radiograph (Fig. 6.7 i) showed increasing bony consolidation of the osteolytic area. It should be added that the osteolytic area displayed by radiographs should not be confused with the normal sparseness of trabecular structures in that region.17

Final Diagnosis

Calcifying tendinitis or bursitis that eroded into the bone.

Comments

When interpreted by themselves, MR images of calcifying tendinitis or bursitis with cortical erosion may lead to misinterpretation. CT scans should be added to enable detection of the calcified structures.

6.1.4 Case 102 (Fig. 6.8)

Case description

Referring physician: orthopedist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 7-year-old boy was noted incidentally to have a posterolateral bony prominence at the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of the humeral diaphysis. Tumor?

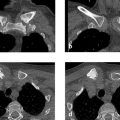

Radiologic Findings

Radiographs of the humerus (Fig. 6.8 a, b) demonstrate a prominence in the area of the deltoid tuberosity. On CT scans (Fig. 6.8 c, d) the cortex of the adjacent humerus appears to be continuous with the prominence. The area within the prominence shows ground-glass opacity adjoining the fat-containing medullary cavity. Bone scans (Fig. 6.8 e) show no abnormalities in either humerus.

Location

The prominence is located in the anatomic region of the deltoid tuberosity.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The harmonious structure of the prominence in the region of a physiologic “roughness” or bony protrusion with a rough surface (tuberosity) at the attachment of the deltoid muscle, plus the incidental detection and negative bone scan, are not consistent with a true pathologic finding. The prominence appears to contain cancellous bone, which would explain the ground-glass attenuation on CT. This makes the diagnosis clear, and there is no need to consider a range of basic entities.

Synopsis and Discussion

If the child had pain in the affected region and a positive bone scan, the differential diagnosis would still include a stress-induced enthesiopathy (see Case 75, Case 77, Case 103, Case 104, and Case 151). Other possibilities such as a flat osteochondroma or osteoblastoma lack any real basis, as we are dealing with a physiologic finding that varies in different individuals depending on body habitus and stress levels.

Fig. 6.9 shows the case of a 53-year-old man with nonspecific complaints in his left upper arm 3 years after receiving an early-summer meningoencephalitis vaccination at that site. Even at the time of imaging, the symptoms subsided in response to local massage. The imaging studies had been ordered for investigation of a shoulder contusion, but the patient asked that imaging be extended to cover his left upper arm. The deltoid tuberosity appears prominent on MRI (Fig. 6.9 a, b) and contains cancellous bone and fatty tissue. The adjacent medullary cavity contains normal fat plus a linear, medially angled structure that is hyperintense in the water-sensitive sequence (Fig. 6.9 a) and is devoid of signal on the T1w image (Fig. 6.9 b). This may represent a vascular structure. CT images in various projections (Fig. 6.9 e–h) show disorganized intraosseous bone tissue in which fatty marrow spaces can be seen. Anatomic diagrams of the humerus (Fig. 6.9 c, d) illustrate the complex anatomy in the region of the deltoid tuberosity, especially in the posterior view (Fig. 6.9 c), with a vascular foramen and the groove for the ulnar nerve. It is easy to see how regressive changes might develop in and on this enthesis in response to repetitive stresses, including focal inflammation with intramedullary involvement, fat necrosis leading to metaplastic bone formation, and other changes. Any suspicion of a tumor process (“A tumor cannot be excluded.”) is untenable, and further follow-ups are unnecessary. The clinical complaints cannot be attributed to the finding, which we therefore classify as incidental.

Final Diagnosis

Slightly prominent but normal deltoid tuberosity.

Comments

Incidental findings, especially at an enthesis, most likely represent normal findings or variants. Cases of this kind do not require follow-up, which would cause needless concern for the patients and their families.

6.1.5 Case 103 (Fig. 6.10)

Case description

Referring physician: pathologist.

Prior history and clinical question: A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer underwent a bone scan for investigation of mild back pain. The scan showed slight focal uptake in the proximal left humerus. The patient had no complaints in that area; she was otherwise healthy with no evidence of metastasis. She was an avid golfer.

Radiologic Findings

The whole-body bone scan (Fig. 6.10 b) was normal except for a focal area of slightly increased uptake in the left proximal humeral diaphysis. The radiograph (Fig. 6.10 a) showed a circumscribed lucency in the slightly prominent deltoid tuberosity, corresponding to the site of increased uptake. MRI (Fig. 6.10 c–e) showed no significant pathology at the site of increased uptake.

Location

As described above, the osteolytic focus showing moderate tracer uptake is located in the deltoid tuberosity, and thus in an enthesis.

Pathoanatomic Background of the Findings

The location of the radiologic findings is suspicious for an enthesiopathy. A solitary cortical metastasis or primary bone tumor (e.g., osteoid osteoma) is unlikely due to the incidental nature of the finding (see Normal variant or malformation? and Synopsis and Discussion below).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree