EMBRYOLOGY

Bowel Development

- •

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract forms from 1 straight tube

- ○

Foregut : Forms esophagus, stomach, and duodenum

- ○

Midgut : Small intestine and colon up to splenic flexure

- –

Connected to yolk sac

- –

Portion that lengthens and loops around superior mesenteric artery (SMA)

- –

- ○

Hindgut : Descending colon, sigmoid, rectum, and upper anal canal

- –

Caudal end of hindgut terminates in cloaca

- □

Cloaca (Latin for sewer) is common chamber with early communication between the urinary, GI, and reproductive tracts

- □

- –

- ○

- •

Physiologic herniation

- ○

Length of midgut increases rapidly and is greater than body can accommodate so it herniates into base of umbilical cord

- ○

It rotates 90°counterclockwise around axis of SMA and returns to the abdomen after total rotation of 270°

- ○

Abdominal wall closes around base of cord (umbilical ring)

- ○

Physiologic hernia is commonly seen on early 1st trimester scans but the bowel should be back within the abdomen by 12 weeks gestational age

- ○

An omphalocele results from failure to complete physiologic herniation or close umbilical ring

- ○

- •

Rectum forms when urorectal septum divides cloaca into rectum posteriorly and urogenital sinus anteriorly

- ○

Cloacal membrane ruptures by beginning of 8th week, creating anal opening

- ○

Urogenital sinus will divide to form bladder and in females, the vagina

- ○

SCANNING APPROACH AND IMAGING ISSUES

Techniques and Sonographic Appearance

- •

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) scan of the abdomen requires documentation of stomach, kidneys, bladder, umbilical cord insertion site, and umbilical cord vessel number

- ○

Diaphragm, esophagus, small intestine, colon, gallbladder, and liver should also be examined but is not required as part of the standard midtrimester scan

- ○

- •

Stomach is seen as a fluid-filled structure in the left upper quadrant and is one of the 1st organs identified

- ○

Document heart and stomach are on same side, and it is anatomic left of fetus (normal situs)

- –

Opposite sides are seen in heterotaxy syndromes

- –

- ○

Changes in size and shape during exam

- ○

Fluid may intermittently be seen to enter the duodenal bulb but should never persist

- –

A persistently dilated duodenum is never normal and suspicious for duodenal atresia

- –

- ○

- •

Fluid must be visualized on both sides of the umbilical cordinsertion in a transverse section of the fetal abdomen

- ○

Stimulation of fetal movement may be necessary to create a more favorable acoustic window, especially in 3rd trimester when the fetal knees are often tucked up against abdominal wall

- ○

- •

Normal cord contains 2 arteries and 1 vein

- ○

May be visible at cord insertion site, but easiest way to confirm is color Doppler showing umbilical arteries on either side of bladder

- ○

- •

Diaphragm appears as a thin, arched, hypoechoic band

- ○

It is imperative that it be completely imaged from front to back, which is best done in the sagittal plane

- ○

If viewed only in the anterior coronal plane, a congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) may be missed

- ○

- •

Esophagus is not normally seen on fetal imaging, but a blind-ending, fluid-filled pouch may be seen in the fetal neck in esophageal atresia

- ○

Use color Doppler to ensure that the fluid-filled structure is between the neck vessels

- ○

- •

Bowel

- ○

In early 2nd trimester, often appears as intermediate echogenicity “filler” between the solid organs, bladder, and stomach; higher frequency transducers may show distinct bowel loops

- ○

Normal meconium-filled colon often prominent near term

- ○

Anal dimple best seen on an axial view of perineum

- –

Anal mucosa is echogenic and surrounded by hypoechoic muscles of the anal sphincter, creating a target or doughnut appearance

- –

- ○

- •

Fetal liver is relatively large and extends across the upper abdomen with the left lobe anterior to stomach

- ○

Major contributor to the abdominal circumference (AC)

- ○

Both portal and hepatic veins seen on color Doppler

- ○

Gallbladder may be seen, especially in the 3rd trimester, and should not be confused with an abdominal cyst

- ○

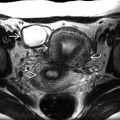

Approach to the Abdominal Wall

- •

Is the abdominal wall intact?

- ○

Gastroschisis (most common abdominal wall defect) is generally located to the right of the umbilical cord insertion and is not covered by a membrane

- –

Small bowel is the most commonly extruded organ, although stomach, large bowel, and other structures may also be involved

- –

- ○

Omphalocele involves extrusion of bowel into the base of the umbilical cord

- –

Covered by a membrane; umbilical cord inserts on this membrane

- –

May rarely rupture; in these cases, it may be difficult to distinguish from gastroschisis

- –

- ○

Defects may also occur in more unusual locations

- –

Low, suprapubic mass may be associated with bladder or cloacal exstrophy

- □

Both will have absent bladder, but cloacal exstrophy will also have extruded bowel described as appearing like an elephant trunk

- □

- –

Supraumbilical defect associated with diaphragmatic and cardiac abnormality is seen in pentalogy of Cantrell

- –

Other unusual or bizarre abdominal wall defects may be seen in cases of amniotic bands or body stalk anomaly

- –

- ○

- •

Is the fetus freely mobile?

- ○

In body stalk anomaly , the fetus is “stuck” to the placenta, and the umbilical cord is absent or very short

- ○

A fetus entrapped within amniotic bands may also be tethered in one position

- –

Look for strands of membrane or other defects, such as unusual facial or cranial clefts

- –

- ○

Approach to the Gastrointestinal Tract

- •

Is the abdomen normal in size?

- ○

Per AIUM guidelines, the AC is measured at the skin line on a true transverse view at the level of the junction of the umbilical vein, portal sinus, and fetal stomach

- ○

AC is utilized with other biometric parameters to calculate the fetal weight/average gestational age

- ○

AC below the normal range

- –

Generally, the most affected parameter in growth restriction

- –

May also measure small when normal abdominal contents are outside the abdomen (e.g., gastroschisis, omphalocele) or up in the chest (i.e., CDH)

- –

- ○

AC above the normal range

- –

Macrosomic fetus of a diabetic mother

- –

Overgrowth syndromes, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann, may also exhibit increased AC size, primarily due to enlarged kidneys and liver

- –

AC often increased in fetuses with large abdominal masses, dilated bowel, or distended bladder

- –

- ○

- •

Is the stomach normal?

- ○

A fluid-filled stomach should reliably be identified after 14 weeks

- –

If not seen, short-term follow-up required to confirm its presence or absence

- –

Ensure that it is not in an abnormal location, such as within the chest in a CDH

- –

- ○

Small/absent stomach

- –

Esophageal atresia ± tracheoesophageal fistula

- □

Look for blind-ending pouch in neck

- □

Will have significant polyhydramnios by 3rd trimester

- □

- –

May be seen in cases of decreased swallowing (e.g., neurologic disorder)

- –

- ○

Large stomach

- –

Often a transient finding or may be seen in evolving, distal GI obstructions

- –

Double bubble sign (dilated stomach and duodenum) is seen in duodenal atresia

- –

- ○

- •

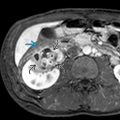

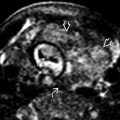

Is there an abdominal mass?

- ○

Masses should be characterized as to their location and appearance (cystic, solid, or complex; vascular or nonvascular) to narrow the differential diagnosis

- ○

Cystic masses in the abdomen are relatively common

- –

Many of these are related to the urinary tract and include cystic kidneys, lower urinary tract obstruction, and ovarian cysts

- –

GI causes include

- □

Bowel atresia : Look for peristalsis

- □

Meconium pseudocyst : Irregular cystic mass, which forms after bowel perforation; look for other sequelae, including peritoneal calcifications

- □

Enteric duplication cyst : Look for gut signature

- □

Mesenteric cysts/lymphangioma

- □

Persistent cloaca occurs when genitourinary tract and colon never separate

- □

- –

- ○

Solid masses are less common; the differential diagnosis starts with the organ of origin

- –

The most common liver mass is a congenital hemangioma , which usually has prominent vascularity

- –

Bulk of a sacrococcygeal teratoma is exophytic but may extend into pelvis/abdomen

- □

Rarely may be only intrapelvic with no external component

- □

- –

Fetus-in-fetu is a mixed solid/cystic mass and is often quite large

- □

Calcifications common; bones and vertebrae may be seen

- □

- –

- ○

- •

Are there calcifications in the abdomen?

- ○

Calcifications on the surface of the liver are actually in the peritoneum

- –

These correlate strongly with intrauterine bowel perforation

- –

Look for associated echogenic or dilated bowel loops, small amounts of ascites, &/or meconium pseudocysts to add weight to this diagnosis

- –

- ○

Calcification in the liver parenchyma concerning for infection, most commonly cytomegalovirus

- ○

Calcifications in the bowel lumen indicate admixture of meconium and urine in the setting of abnormal distal bowel and bladder development

- –

These “meconium marbles” roll within the bowel lumen with peristalsis

- –

Look carefully for the anal dimple to detect associated anal atresia

- –

- ○

- •

Does the bowel appear echogenic?

- ○

A high-frequency transducer may give the false impression of echogenic bowel

- –

Confirm the finding is persistent with a lower frequency transducer (< 5 MHz)

- –

- ○

Bowel is not abnormal unless it is as bright as bone

- ○

Fetal ingestion of blood from a recent bleed is a common benign cause and resolves spontaneously

- ○

Evaluate for pathologic causes, including aneuploidy, infection, cystic fibrosis , and early bowel abnormalities, such as atresia , before the bowel becomes dilated

- ○

May be seen in bowel ischemia in association with severe growth and hemodynamic stress as in twin-twin transfusion

- ○

- •

Is there ascites?

- ○

Care should be taken to differentiate true ascites from pseudoascites , a potential pitfall created by the hypoechoic abdominal wall musculature

- ○

Ascites may be 1st sign of impending hydrops

- –

Look for other evidence of hydrops (pleural and pericardial effusions and skin edema)

- –

- ○

Chest masses may compromise venous and lymphatic return and cause isolated ascites without generalized hydrops

- ○

May also result from perforation of an abdominal viscus , either bowel or bladder

- ○

PHYSIOLOGIC HERNIATION