Acute Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Michael D. Darcy

Angiography and embolization are a critical component of the modern management of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, not only providing important diagnostic information but also potential lifesaving therapy. Generally, these procedures can be performed with high level of success and low complication rates.

Indications

1. For upper GI bleeding (UGIB), endoscopy is usually the first approach because a diagnosis can be made in the majority of cases and the bleeding can be treated at the same time by injection, heater probe coagulation, etc. Angiography is usually not used for diagnosis but instead is used to manage ongoing hemorrhage (usually with embolization). Indications include the following:

a. Bleeding too vigorous for the endoscopist to be able to define the source

b. Bleeding not controllable by endoscopic therapy

c. Inability of the patient to undergo endoscopy for medical or anatomic reasons

d. Lack of availability of a qualified endoscopist

2. For lower GI bleeding (LGIB), endoscopy is much more difficult and less often used as the initial approach. Angiography can be used to identify the source of bleeding in planning for surgery, but most often, the intent of angiography is to localize and stop the bleeding. Situations in which angiography, with planned embolization, is indicated include the following:

a. Ongoing bleeding documented by tagged red blood cell (RBC) scan or computed tomography (CT) scan. Because these studies have better sensitivity for detecting bleeding, angiography is usually not indicated if these studies are negative. These procedures can detect bleeding at rates of 0.1 mL per minute for tagged RBC scan, 0.3 mL per minute for CT (1), and 0.5 to 1.0 mL per minute for angiography.

b. For massive LGIB, one may proceed to angiography without waiting for a scan to confirm bleeding.

c. Angiography can be indicated to look for a structural lesion in patients with intermittent chronic LGIB.

Contraindications

Absolute

1. Given that angiography and embolization may be needed as lifesaving procedures, there are no absolute contraindications.

2. History of life-threatening contrast reaction is a serious contraindication, but rapid steroid preparation can be given if angiography is required to stop critical hemorrhage.

Relative

1. There are several relative contraindications that may help you to decide not to do an arteriogram especially if the indications are marginal in the first place.

a. Renal insufficiency

b. Contrast allergy

c. Uncorrectable coagulopathy

d. If the rate of bleeding is massive, surgery may be preferable to angiography because angiography may not be able to control the bleeding as quickly as surgery.

Preprocedure Preparation

1. History and physical exam

a. Adequate history may provide clues as to the source of bleeding. For example, history of recent polypectomy in a patient with LGIB would point to post polypectomy bleeding, but significant recent vomiting in a person with UGIB would suggest a Mallory-Weiss tear.

b. Other medical conditions (especially cardiac and pulmonary conditions and allergies) that might increase the risk of angiography should be assessed.

2. Ensure adequate monitoring.

a. Automated BP is essential because UGIB patients can become hypotensive.

b. Electrocardiogram (ECG), pulse oximetry, and capnography—loss of blood and dilution of the blood pool by crystalloid infusion decreases the oxygencarrying capacity of the blood, increasing the potential for cardiac ischemia, and possibly arrhythmias or infarcts.

c. Body temperature—patients can get hypothermic due to transfusion of large amounts of fluid. Hypothermia can induce coagulopathy by reducing the effectiveness of various clotting factors. Keep patients covered, use blood warmers, and consider use of warming blankets.

3. Resuscitation efforts—although resuscitation is critical, it cannot be performed as an isolated event prior to angiography. Some patients cannot be stabilized until the bleeding is actually stopped. Thus, angiographic therapy needs to be undertaken quickly, and resuscitation should be an ongoing process that continues into the angiography suite.

a. Ensure adequate intravenous (IV) access for infusion of boluses of saline or transfusion of blood. Typically, two large-gauge (16 gauge) IVs are recommended.

b. Correct hypotension—initially, saline bolus infusion is used, but blood transfusions may also be needed in order to maintain hemoglobin content and enhance the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

c. Correct coagulopathy—embolization is much less effective when done in a coagulopathic patient because the embolic agents often only initiate clot formation.

Procedure

1. Diagnostic angiography

a. A sheath must be placed in the artery to avoid losing access if the angiographic catheter becomes occluded during embolization. A femoral artery approach is used in most cases, barring more proximal occlusions.

b. Aortograms are usually not performed because visualization of contrast extravasation into the GI tract requires more selective injection.

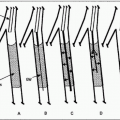

c. The vessel selected first should be based on suspicion of the likely source of bleeding according to history, clinical signs, as well as localization provided by tagged RBC scans or CT scans. If there is no good clue as to the source, some prefer to select the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) first to study the rectum before the overlying bladder fills with contrast. For suspected UGIB, the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries (SMA) are the primary targets. For LGIB, the IMA and SMA need to be studied first. However, if these runs are negative, the celiac artery (e.g., gastroduodenal artery [GDA]) should be injected because rapid distal duodenal bleeding can present as LGIB. If extravasation is not seen on injection of the main trunks, more subselective injection may be needed. For duodenal or gastric fundus bleeding, the GDA, or left gastric arteries, respectively, should be studied. Choice of subselective injections can be guided by localization provided by tagged RBC scan, CT, or endoscopic findings.

d. Contrast injections are at a rate of 5 to 6 mL per second for celiac and SMA, and 2 to 3 mL per second for the IMA. Four- to five-second long injections help maximize visualization of contrast extravasation while avoiding overlap between the arterial injection and the venous phase.

e. Filming should be continued until the venous phase has cleared out to help distinguish contrast extravasation from persistent venous opacification. Although digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is the standard technique, viewing the images in nonsubtracted mode is important to distinguish true extravasation from misregistration artifacts caused by respiratory or peristaltic motion. Use of glucagon before the angiogram can help reduce artifacts from bowel motion.

f. Unfortunately, GI bleeding is often intermittent and an angiogram may be negative even after positive tagged RBC scans. If a bleeding source is not identified, some authors (2,3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree