Arteriovenous Malformations of the Viscera and Extremities

Robert J. Rosen

Allison Borowski

Vascular malformations include a wide range of clinical and anatomic problems, ranging from lesions of cosmetic significance in adults to life-threatening conditions in infancy. Management of vascular anomalies represents a long-term commitment to the patient and family, and one in which there will often be limited support from other clinical specialists. Once treatment is undertaken, you will become the primary clinician caring for the patient. Therefore, it is essential to make the correct diagnosis, be aware of its natural history, make an appropriate risk-benefit analysis, choose the correct procedure, and be able and willing to deal with potential complications.

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) recently devised an expansive classification system of vascular anomalies (1). The new system uses immunohistologic data to differentiate several types of vascular lesions into a comprehensive and detailed scheme, which is beyond the scope of this chapter. Therefore, as in many of the previous classifications (2), the authors characterize vascular anomalies by hemodynamic properties (slow vs. fast flow) and are subcharacterized by the type of anomalous channels present as well as by their associated syndromes. For practical purposes, it is helpful to divide these lesions into five main categories, each with its own distinct clinical presentation, natural history, and treatment options:

1. Hemangiomas

2. High-flow arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and congenital fistulas

3. Low-flow venous malformations (VM)

4. Congenital venous syndromes (Klippel-Trenaunay, Parkes-Weber, etc.)

5. Lymphatic malformations (LM)

The term “hemangioma” is widely misused and should only be applied to the specific benign vascular tumor of infancy and childhood that is composed of endothelial cells (3). Infantile hemangiomas appear sometime after birth, usually within the first 2 months of life. These lesions follow a distinctive course of proliferation followed by spontaneous involution over a period of years. Most of these lesions will therefore require no specific treatment, whereas some will require early intervention for life-threatening high output states, bleeding or ulceration, interference with visual development, respiration, or feeding. An increasing number of these lesions are being surgically removed or treated with laser therapy early in infancy to avoid the psychosocial trauma of a disfiguring condition (4). Medical treatment of these lesions includes administration of propranolol, a well-tolerated, nonselective, adrenergic receptor blocker. Studies have shown promising results with signs of regression reported as early as the first month of treatment (5). Some lesions will leave abnormal skin or tissue even after involution, which can be treated with plastic surgical revision.

In contrast, congenital hemangiomas are fully formed at birth and may rapidly involute (rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma [RICH]). The rare noninvoluting congenital hemangioma (NICH) can be treated surgically or with laser therapy and will not respond to propranolol. The management of congenital hemangiomas and other vascular tumors of childhood is a highly complex subject and is not discussed further in this chapter.

Indications

1. Hemorrhage

2. Pain

3. Ulceration

4. High-output cardiac state

5. Mass causing interference with normal activity

6. Lesions which interfere with normal growth and development

7. Disfiguring lesions

Contraindications

Absolute

1. Anatomy such that the embolic material cannot be contained within the target site

Relative

1. Minimal likelihood of clinical improvement—malformations are usually isolated benign lesions in otherwise young healthy patients. Improving the angiographic picture does not always improve the patient’s overall condition.

2. Contraindications to angiography

a. Severe anaphylactic reaction to iodinated contrast

b. Acute renal failure

c. Uncorrectable coagulopathy

3. Pregnancy

4. Infection within the target vasculature

Preprocedure Preparation

1. Preprocedural imaging

a. Ultrasound studies are easily performed in the office setting and provide valuable information on depth and flow characteristics but do not usually provide enough detailed anatomic information to plan an intervention.

b. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide detailed information on size, location, flow characteristics, and the relationship to surrounding structures (6). MRI, including magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and dynamic studies, has become the mainstay in AVM imaging and is often the only modality which clearly demonstrates slow flow malformations. It should be kept in mind that MRI studies in pediatric patients will require sedation or anesthesia; thus, these studies should be performed only when the findings will affect treatment decisions.

2. Routine preprocedural laboratory studies should include complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, creatinine, and coagulation studies. Goals for preoperative testing include an international normalized ratio (INR) <2.0 and platelet count >50,000 per µL for both venous and arterial procedures.

3. Communication with the patient’s primary physician is essential, and formal consultations with appropriate specialists may be required depending on the type and complexity of the malformation.

4. In preparation for sedation or general anesthesia, patients are made nil per os (NPO) for 8 hours according to hospital guidelines. The authors perform almost all embolization procedures under general anesthesia for patient comfort, the safety of close physiologic monitoring, and the ability to control respiration and movement during angiography. When respiratory control is not required, as in extremity lesions, we routinely employ laryngeal mask airway (LMA) anesthesia, which is more comfortable in the postprocedure period. Because many of these patients will require repeat embolizations, it is important to make the treatments as psychologically atraumatic as possible, especially in pediatric patients.

5. Once the patient has been sedated, a preprocedural dose of antibiotics (typically cefazolin) as well as steroids (the authors use dexamethasone) are administered.

Procedure

High-Flow Malformations

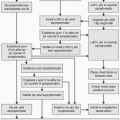

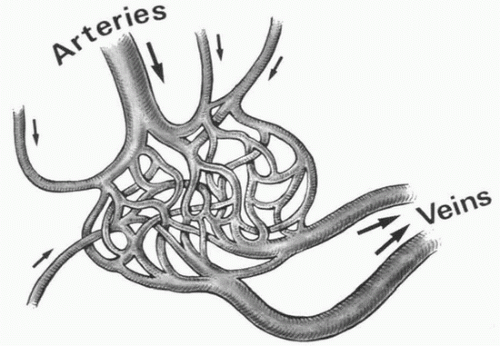

By definition, high-flow malformations involve an abnormal arteriovenous connection at something larger than capillary level. These can range from direct fistula-like connections (most commonly seen in the lung, kidney, and carotid-cavernous lesions) to small vessel communications with a nidus, or central network, of variable size vessels (Fig. 21.1). The treatment goal is to eliminate the abnormal shunt, which can be a complex undertaking.

1. Perform detailed selective angiography to determine the type of malformation, feeding vessels, patterns of venous drainage, and regional collateral pathways, which provide a safety margin to prevent ischemia but also have the potential to resupply the malformation. Given the detailed information available from CT and MRI, we generally do not perform diagnostic angiography until the time of planned intervention.

2. Once the anatomy has been defined, superselective coaxial catheterization of the feeding arterial vessels is carried out. The coaxial system is essential to protect proximal vessels if the embolic material becomes adherent to the catheter tip as well as providing secure access for repeated depositions of embolic material without having to perform a new selective catheter placement each time.

3. The choice of embolic material is critical and depends on the vessel size and flow characteristics. The ideal result is elimination of the nidus while preserving flow to normal vessels. Note: Proximal occlusion of the feeding artery is ineffective because it sacrifices future transvascular access to the nidus and promotes collateral resupply.

4. Consideration must be given to the distribution of the embolic material once it is injected because patterns of flow may change rapidly during the embolization itself, resulting in reflux or nontarget embolization.

FIGURE 21.1 • High-flow AVM. Treatment must be aimed at eradicating the nidus as virtually all have multiple feeding arteries and proximal occlusion results in recruitment of collaterals. |

5. There is no ideal embolic agent for all AVMs. The agents used include:

a. Proximal occluding devices including coils, plugs (such as the AMPLATZER Vascular Plug, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN), and detachable balloons: These may be appropriate to treat fistula-like lesions where a simple interruption of a macroscopic arteriovenous connection is required. These devices can also be useful in protecting normal vessels from distal embolization, redirecting flow, or preventing loss of embolic materials into the venous circulation in certain situations. They are not suitable for use as the definitive embolic agent in complex malformations and will only hinder subsequent treatment.

b. Microspheres: These can be useful in “pruning” small vessel arteriovenous shunting, but recanalization generally occurs with recurrence of the lesion. This agent is best used for preoperative embolization to reduce bleeding during resection or to manage ischemic problems distal to an AVM causing a “steal” phenomenon.

c. Liquid “casting” agents: These offer the possibility of permanently filling and occluding the nidus of the malformation. Use of these agents requires specialized training and experience in terms of preparation and delivery techniques.

(1) n-Butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue (Codman Neuro, Warren, NJ) is an adhesive that rapidly polymerizes on contact with any ionic medium and is usually mixed with Ethiodol. The oil is used to slow glue polymerization time, increase its viscosity, and provide radiopacity (7). It is best to limit oneself to a few ratios (Ethiodol:glue) and become familiar with their behavior (the authors most commonly employ a 1:1 mixture).

(a) Glue is injected through a microcatheter either as a series of small depositions (0.2 to 0.8 mL) pushed by dextrose 5% water in a small vessel nidus or as a “continuous column” when dealing with larger vessels or faster flow.

(b) Flow control using balloon catheters is sometimes employed, but in most situations, it is preferable to use forward blood flow to carry the agent deep into the nidus.

(2) Ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx, ev3, Plymouth, MN) is a nonadhesive polymer that is used in combination with the solvent dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Onyx has primarily been used in neurointerventions

where its safety profile has been well established. At present, it is only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for neuroembolization procedures in the United States but has been used for peripheral lesions in other countries.

where its safety profile has been well established. At present, it is only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for neuroembolization procedures in the United States but has been used for peripheral lesions in other countries.

(a) It is injected slowly and continuously through an Onyx-compatible microcatheter, forming a lava-like cast of the vessels over a period of minutes. Onyx deposition does not rely on forward flow-like glue. Therefore, it must be deposited directly in the nidus, which is often a difficult task if tortuous vessels need to be traversed.

(b) Advantages of Onyx include no risk for catheter gluing/fracture, ability to conform to tortuous vessels, and ease of control. Disadvantages include ischemic complications if the cast reaches very small vessels and the fact that the marked radiopacity of the agent can obscure anatomic detail in subsequent embolization procedures and scans. Additionally, Onyx embolization can be quite time-consuming and costly, especially because multiple vials are usually required.

d. Absolute ethanol used intra-arterially in high-flow malformations can be highly effective by causing rapid thrombosis and endothelial damage, resulting in permanent occlusion (8

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree