Benign Lesions

Mammography is a screening test whose major application is the earlier detection of breast cancer. Using two view, conventional mammography, some cancers have characteristic appearances with spiculated margins. However, many cancers, using conventional two-view mammography have non-specific appearances. Mammography also reveals many unsuspected benign breast processes. Many benign changes are easily recognized and can be ignored. Others, however, have characteristics that cannot be easily distinguished from the less characteristic morphologic changes of breast cancer. Given that breast cancers are merely an alteration of normal cells, it is not surprising that the appearance of malignant lesions overlaps with the appearance of some benign breast changes. With the development of digital breast tomosynthesis, our criteria for distinguishing benign lesions from malignant will improve as we are better able to evaluate the margins of lesions and the x-ray attenuation of lesions, but, until this technology is widely adopted, the old criteria must be applied.

Many findings are never associated with breast cancer or are so unlikely to be breast cancer that they can be classified as benign. Other lesions are very unlikely to be malignant, but there is still a very small possibility that they represent an unusual presentation of cancer. These are classified as probably benign. Based on work done by Sickles (1), these lesions should have less than a 2% chance of malignancy and can be followed at short interval. I believe that there is a general consensus that, if a lesion has a greater than 2% to 5% of being a breast cancer, then a biopsy is warranted.

When a possible abnormality is detected, the first decision, after determining that it is real and ascertaining its location, is to try to determine what it is and whether it should raise concern. There are many findings that appear on mammograms that are clearly benign and should not elicit any further evaluation. Recognizing them and realizing that they are insignificant is an important aspect of mammographic evaluation. There are a number of masses that are benign, have a typical appearance on the mammogram, and rarely require any additional evaluation (Table 14-1). Most calcifications that appear in the breast are due to benign processes. Many of these have typical morphologic characteristics and do not require any further evaluation (Table 14-2).

Benign Masses can be Ignored

Raised Skin Lesions

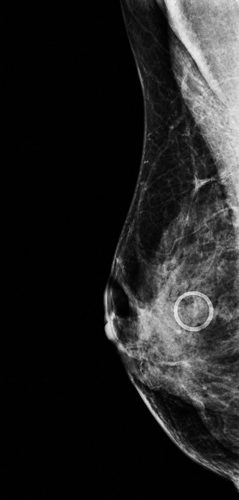

Lesions that are on the skin may need a dermatologic evaluation, but, with the exception of malignant melanoma (which is not visible by mammography), or the very rare lesion that metastasizes to the breast, the only consequences of skin lesions that are visible by mammography are that they might be mistaken for intramammary lesions. Because very little of the skin of the breast is imaged in tangent to the x-ray beam, almost anything that is on or in the skin projects over the breast tissue. Fortunately, most skin lesions are not visible on a mammogram. However, lesions that are firm, raised, do not flatten against the skin with compression, and have an air/soft-tissue interface may appear and project as masses on the mammogram and appear as if they are in the breast. When the technologist finds a hard, raised skin lesion it helps if she marks it so that the radiologist will not be confused. We use semiradiopaque self-sticking rings and place them around the skin lesion to identify them on the mammogram (Fig. 14-1). Markers used to identify skin lesions have been called mole markers. This is, in fact, a misnomer. Moles, or nevi, do not show up on mammograms. It is not the pigment that makes a lesion radiopaque; it is the fact that it has an air/soft-tissue interface that makes the skin lesion visible.

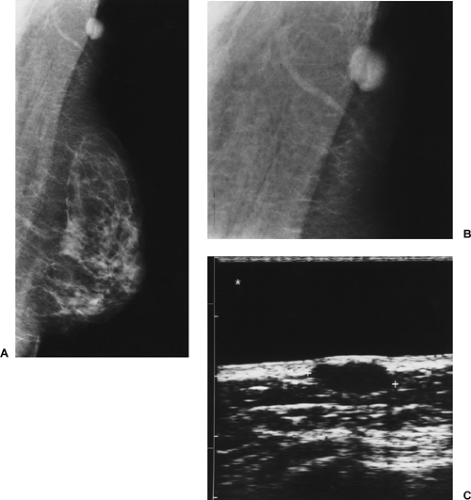

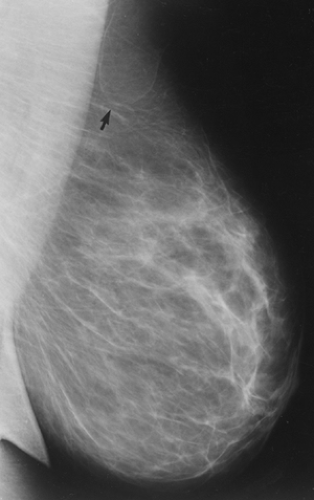

Seborrheic keratoses are the most common skin lesion that is visible on the mammogram. These are benign skin lesions that are associated with aging (Fig. 14-2). They appear wartlike with a verrucoid surface that is frequently visible on the mammogram, with air trapped in the irregular cracks in the surface of the lesion. Air trapped around the periphery of the lesion at the time of compression, which highlights the margin, is frequently what makes these lesions visible on the mammogram.

Epidermal inclusion cysts, commonly called wens, may also appear on the mammogram (Fig. 14-3). I have been

unable to determine from the pathology literature whether these are distinct or the same as sebaceous cysts, but I believe that many lesions that are called sebaceous cysts are actually epidermal inclusion cysts. The sebaceous cyst should merely be an obstructed sebaceous gland. It would be surprising that these would recur once opened. However, the epidermal inclusion cyst actually represents epidermis that is trapped beneath the skin by a developmental invagination of the epidermis, forming a space lined by epidermis. Any secretions or sloughed skin cells accumulate in these lesions. If the cyst lining (which is actually epidermis) is not removed, then these lesions will recur, with the cyst refilling.

unable to determine from the pathology literature whether these are distinct or the same as sebaceous cysts, but I believe that many lesions that are called sebaceous cysts are actually epidermal inclusion cysts. The sebaceous cyst should merely be an obstructed sebaceous gland. It would be surprising that these would recur once opened. However, the epidermal inclusion cyst actually represents epidermis that is trapped beneath the skin by a developmental invagination of the epidermis, forming a space lined by epidermis. Any secretions or sloughed skin cells accumulate in these lesions. If the cyst lining (which is actually epidermis) is not removed, then these lesions will recur, with the cyst refilling.

TABLE 14-1 MASSES THAT CAN BE IGNORED | |

|---|---|

|

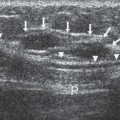

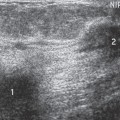

These skin lesions form circumscribed masses that are almost always palpable immediately beneath the skin surface. An inclusion cyst is frequently accompanied by a small visible blackhead, and patients invariably attest that the blackhead has been present for many years and that periodically a foul smelling whitish material exudes from this small opening that is visible on the skin. These lesions can be found on any skin surface, but it has been our experience that they are often found near the inframammary fold or near the axilla. On ultrasound they are found at the junction of the dermis and the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 14-3C). Needle biopsy of these lesions should be avoided since the needle can push the necrotic, oily material from the cyst in which it is contained into the surrounding breast tissue, and this can elicit a dramatic inflammatory reaction.

TABLE 14-2 CALCIFICATIONS THAT CAN BE IGNORED | |

|---|---|

|

Although the diagnosis of a skin lesion is usually obvious on the mammogram and no further analysis is required, if there is any question, and it has not already been done by the technologist, a radiopaque marker can be taped to the lesion. The marker will remain with the projected density on the mammogram, regardless of the x-ray projection. An image obtained with the beam in tangent to the lesion will confirm its cutaneous location. We favor radiopaque circular markers. “BB’s” should be saved for areas of clinical concern.

Intramammary Lymph Nodes

Since the axillary tail of the breast obviously extends into the axilla, it should not be surprising that lymph nodes can be found in the breast itself. Benign intramammary lymph nodes are visible on approximately 5% of all mammograms. They are usually well circumscribed and <1 cm in size. Pathologists, apparently, find lymph nodes on histologic sectioning

in all areas of the breast, but on mammography they are almost always found at the periphery of the parenchymal cone in the upper outer quadrant. Although it is rare, they can sometimes be found below the equator of the breast (2). They are seen mammographically as far as three fourths of the way toward the nipple, but not in the subareolar area. Intramammary lymph nodes have been reported in other parts of the breast. Meyer et al (3) reported two cases in which benign intramammary nodes were biopsied in the medial part of the breast. Since the histology of these was not provided, it is not clear whether these were true lymph nodes or rather the lymphoid tissue that we have seen in other parts of the breast. Regardless, these have been the only two reported cases of lymph nodes found in atypical locations in the breast in which histologic confirmation has been reported. The rarity of this is clear in that the 2 cases came from a series of more than 4,000 breast biopsies. It is probably best to not invoke the diagnosis of a lymph node unless it has the morphologic characteristics and is in the lateral portion of the breast, at the periphery of the tissue.

in all areas of the breast, but on mammography they are almost always found at the periphery of the parenchymal cone in the upper outer quadrant. Although it is rare, they can sometimes be found below the equator of the breast (2). They are seen mammographically as far as three fourths of the way toward the nipple, but not in the subareolar area. Intramammary lymph nodes have been reported in other parts of the breast. Meyer et al (3) reported two cases in which benign intramammary nodes were biopsied in the medial part of the breast. Since the histology of these was not provided, it is not clear whether these were true lymph nodes or rather the lymphoid tissue that we have seen in other parts of the breast. Regardless, these have been the only two reported cases of lymph nodes found in atypical locations in the breast in which histologic confirmation has been reported. The rarity of this is clear in that the 2 cases came from a series of more than 4,000 breast biopsies. It is probably best to not invoke the diagnosis of a lymph node unless it has the morphologic characteristics and is in the lateral portion of the breast, at the periphery of the tissue.

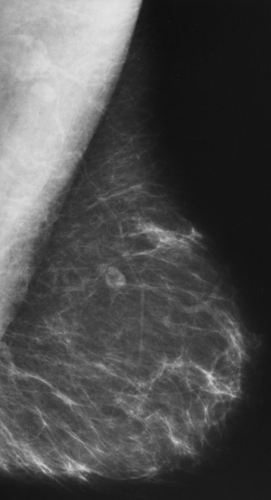

Figure 14-2 The verrucoid appearance of this mass is typical of the benign, cutaneous seborrheic keratosis (arrow) that is projecting over the breast. |

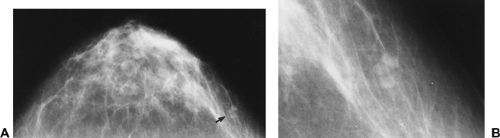

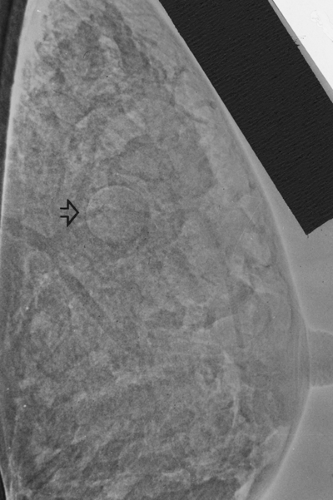

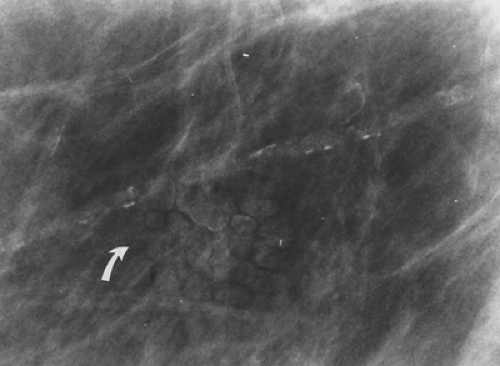

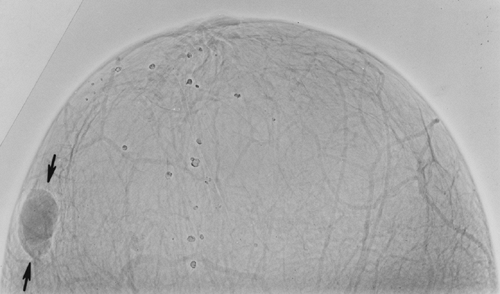

Intramammary lymph nodes have a fairly classic appearance, with an invaginated hilum or “notch.” When fatty infiltrated, they have a typical lucent center (Fig. 14-4), and, when in an appropriate location, they should not be confused with a significant abnormality. When a node becomes almost completely fatty replaced, it may appear as three or more round densities in a horseshoe arrangement (Fig. 14-5).

The diagnosis of an intramammary lymph node should not be considered when a mass is seen in any section of the breast other than the lateral portion, unless the lesion has a clearly defined lucent hilum. If an upper-outer-quadrant lesion does not have the characteristics of a benign intramammary node, including a lucent hilar notch and smooth, sharply defined margins, suspicion should be aroused because not all upper-outer-quadrant masses are benign lymph nodes and 30% to 50% of cancers are found in the upper outer quadrant.

Figure 14-4 Typical appearance of a benign, intramammary lymph node. It is a reniform mass with a fatty (lucent) hilum. No further evaluation is required. |

Figure 14-6 Psoriatic dermatopathic lymph node. This lobulated mass on a xerogram was excised and proved to be a dermatopathic lymph node related to the patient’s known psoriasis. |

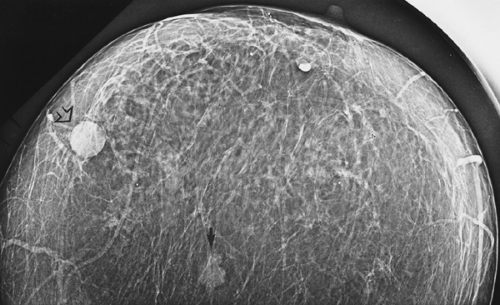

If an intramammary lymph node is enlarged, loses its hilar notch, and becomes rounded, biopsy should be considered. Although intramammary lymph nodes can be hyperplastic or enlarged because of dermatologic problems, such as psoriasis (Fig. 14-6) or other benign inflammatory processes in the breast (4), enlargement can also be due to lymphoma or metastatic spread from an intramammary malignancy to an intramammary lymph node. Lymph nodes that contain metastatic cancer may still remain well circumscribed (Fig. 14-7). The breast should be carefully searched for an occult malignancy. Metastatic spread of breast cancer to an intramammary node carries the same worsened prognostic significance as axillary nodal involvement (5). Lymph nodes can also be seen close to the chest wall. They occur in the lateral axillary chain and may extend down the chest wall in the prepectoral chain posterior to the breast (Fig. 14-8).

Fat-Containing Lucent Lesions

Because of the low x-ray attenuation of fat, lesions that contain fat are radiolucent. Lesions that contain fat are never malignant. Completely radiolucent lesions, including lipomas (Fig. 14-9), traumatic oil cysts (Fig. 14-10), and galactoceles (Fig. 14-11), are never malignant. Because the normal breast contains numerous locules of fat, a lipoma

may not always be evident. Galactoceles are extremely rare. All of these masses may be evident on clinical breast examination, and the oil cyst in particular may present as a very hard mass. None requires surgical excision.

may not always be evident. Galactoceles are extremely rare. All of these masses may be evident on clinical breast examination, and the oil cyst in particular may present as a very hard mass. None requires surgical excision.

Mixed-Density Lesions

Encapsulated lesions that contain fat are never malignant. The mammary hamartoma (fibroadenolipoma) contains various mixtures of fat and dense tissue within a fibrous capsule (Fig. 14-12). This typical, benign appearance is so characteristic that further intervention is not warranted. There is one case report of a lesion with similar characteristics that was reportedly a cystosarcoma (6). The term phylloides tumor has replaced cystosarcoma phylloides. Sarcomas of the breast are invariably dense lesions. Phylloides tumors are also dense. Given this single, isolated occurrence and the uncertainty of the accuracy of the histologic evaluation, it is reasonable to state that an encapsulated lesion containing fat is always benign.

Multiple Rounded Densities

In our screening program, multiple rounded densities are found either in one breast or bilaterally in approximately 0.5% of women. When three or more multiple, similar findings appear on the mammogram, this usually indicates a benign process. Sickles has called this the rule of multiplicity. Of course, this does not apply to multiple lesions that have the typical morphologic characteristics of breast cancer.

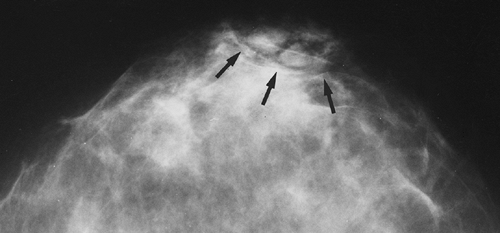

Multiple rounded densities may actually be nothing more than normal breast tissue with a rounded or lobulated appearance. Although the mammographic appearance may suggest multiple round, potential masses, these sometimes prove to be merely fibroglandular tissue. The rounded contours are likely due to the segmentation of the breast tissue by Cooper’s ligaments (Fig. 14-13).

Figure 14-12 Hamartoma (arrows). This mixed lesion contains fat and fibroglandular tissue. It is benign and, though palpable, requires no further evaluation. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree