Cancer Imaging for Interventional Radiologists

Ajay K. Singh

Rathachai Kaewlai

Interventional oncology is a rapidly emerging subfield within interventional radiology. Many interventional radiologists are familiar with indications, contraindications, and techniques of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures for patients with cancer. However, it is crucial for interventional radiologists to incorporate cancer imaging into their practice because this can improve diagnostic accuracy, guide interventions, and enhance the quality of consultation with referring physicians. This chapter provides an overview of imaging for common cancers in the thorax and abdomen (solid organ), which interventional radiologists are most likely to encounter.

Lung Cancer

1. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality, accounting for 25% of all cancer deaths in the United States (1). There are two forms of lung cancer: small-cell and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). NSCLC accounts for approximately 75% of all lung cancers. Patients with NSCLC commonly present with local symptoms caused by the primary tumor, in contrast with those of small-cell carcinoma who frequently present with extensive locoregional spread and metastasis.

a. Chest radiography is usually the first-line imaging exam performed in patients suspected of having lung cancer.

b. Chest computed tomography (CT), including scans through the adrenal glands, is the current standard for staging newly diagnosed lung cancers. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be utilized in patients with symptoms of Pancoast (apical) tumor, chest wall invasion, or spinal canal involvement.

c. Positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for the workup of lung cancer. It is useful to detect abnormalities not seen on CT, thereby improving staging.

d. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) has emerged as a reasonable screening tool for lung cancer, which has shown to reduce lung cancer and all-cause mortality in at-risk individuals. In the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), LDCT reduced lung cancer-specific mortality by 20% (compared with those who had chest radiography) at the expense of a high false positivity rate (24%). Individuals who might benefit from screening, according to the NLST are of age 55 to 74 years, asymptomatic current or former smokers without prior history of lung or other cancers (2).

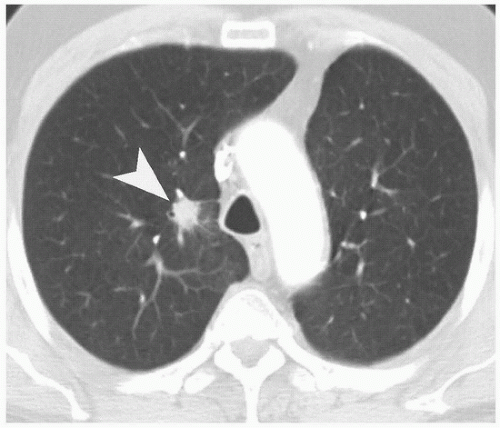

2. Typical presentations of NSCLC on imaging studies include solitary pulmonary nodule/mass, central mass, malignant pleural effusion, and metastasis. Approximately 20% to 30% of lung cancers present as solitary pulmonary nodules (SPN) (3). Indicators of malignancy of SPN are size >3 cm and spiculated margins, although malignant nodules can be small and have smooth margins. The presence of a cavity and lobulation cannot be used to discriminate benign from malignant SPNs. Central tumors often present as a hilar mass, with distal lung volume loss from collapse or consolidation. CT with contrast administration can be used to distinguish an obstructing central tumor from distal collapse. Collapsed lung typically demonstrates avid enhancement, whereas tumor enhancement is relatively minimal. Tumors may invade visceral pleura, chest

wall, diaphragm, pericardium, main bronchus, or other mediastinal structures. Nodal metastasis may involve ipsilateral peribronchial, hilar, mediastinal, or subcarinal lymph node groups and extends to the contralateral side in a later stage. NSCLC staging is based on tumor, node, metastases (TNM) classification, which has therapeutic and prognostic implications.

wall, diaphragm, pericardium, main bronchus, or other mediastinal structures. Nodal metastasis may involve ipsilateral peribronchial, hilar, mediastinal, or subcarinal lymph node groups and extends to the contralateral side in a later stage. NSCLC staging is based on tumor, node, metastases (TNM) classification, which has therapeutic and prognostic implications.

3. Further management of an SPN depends on its size (<8 mm, ≥8 mm), morphology (solid, part-solid, nonsolid), and clinical probability of malignancy. Serial CT follow-ups, positron emission tomography (PET), nonsurgical biopsy, and surgical diagnosis are potential options (4).

4. Adenocarcinoma in situ and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (formerly known as bronchioloalveolar carcinoma [BAC]) are subtypes of adenocarcinoma (Fig. e-75.1). In contrast to other types of adenocarcinoma that tend to invade and destroy lung parenchyma, they spread along the alveolar/bronchiolar wall framework (a pattern called “lepidic growth”). They most commonly present as a solitary nodule, which may have ground-glass appearance and may contain bubbly lucencies. Therefore, tumors have a very good prognosis when localized. However, they may present with diffuse/multifocal consolidations or nodules.

5. Small-cell lung cancers usually present as central tumors. Tumors tend to occur at the main or lobar bronchi with extensive peribronchial invasion and a large hilar or parahilar mass. Extensive mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is common. Small-cell lung cancer has a poor prognosis because most patients present with metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

6. Radiofrequency ablation of lung cancer is generally used for early-stage cancers that are less than 3 cm in diameter and few in number (one or two). It can also be used for pulmonary metastases and in patients who refuse surgery or are poor surgical candidates.

FIGURE e-75.1 • Bronchogenic carcinoma. Axial CT shows a speculated nodule (arrowhead) located centrally in the right upper lobe. |

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Fig. e-75.2) is the most common primary malignancy of the liver that usually occurs in patients with chronic liver disease such as cirrhosis, hemochromatosis, and glycogen storage disease. In the United States, there has been an increasing incidence of HCC within the past 20 years, probably related to chronic hepatitis C infection. HCC usually occurs in the sixth to seventh decades of life, or earlier in high-incidence areas such as Japan.

There are three major patterns of growth of HCC: solitary mass, multifocal masses, and diffusely infiltrating mass. The diffuse infiltrative form may be difficult to diagnose especially in an underlying dysmorphic (cirrhotic) liver.

a. On unenhanced CT, HCC is usually iso- or hypodense compared to the liver. With contrast administration, a typical HCC enhances during the arterial phase and demonstrates rapid washout in venous phase with tumor heterogeneity due to necrosis or hemorrhage. HCC has a propensity to invade adjacent vascular structures, especially portal veins, resulting in hepatic vascular occlusion and abnormal hepatic perfusion (5).

b. On ultrasound, it usually has mixed echogenicity with or without a thin hypoechoic capsule. Tumor hypervascularity may be demonstrated on color Doppler ultrasound.

c. On MRI, appearances of HCC

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree