Plain Film of the Abdomen: Introduction

In recent years, new techniques such as ultrasonography, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging have been used widely and have altered the use of plain films of the abdomen in the evaluation of abdominal diseases. Plain films of the abdomen are still used primarily to assess intestinal perforation (intraperitoneal air) or bowel obstruction or assessment for catheter placement. The plain radiograph is commonly used as a preliminary radiograph before other studies such as CT and barium enema. The yield of plain radiographs is higher in patients with moderate or severe abdominal symptoms and signs than in those with minor symptoms.

Technique and Normal Imaging

The most common plain radiograph of the abdomen is an anteroposterior (AP) view with the patient in supine position. The AP view of the abdomen is also called by the acronym KUB film because it includes the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. When acute abdominal disease is suspected clinically, an erect film of the abdomen and a posteroanterior (PA) view of the chest are also required. Digital imaging is becoming more common, and abdominal images may be viewed on a computer monitor rather than on films.

The abdomen is composed primarily of soft tissue. The density of soft tissue is similar to the density of water, and the difference in density between solid and liquid is not distinguishable on a plain radiograph. The liver is a homogeneous structure located in the right upper quadrant; the hepatic angle delineates the lower margin of the posterior portion of the liver (Figure 8-1). In the left upper quadrant, a similar angular structure, the splenic angle, can be identified by the fat shadow around the spleen (see Figure 8-1).

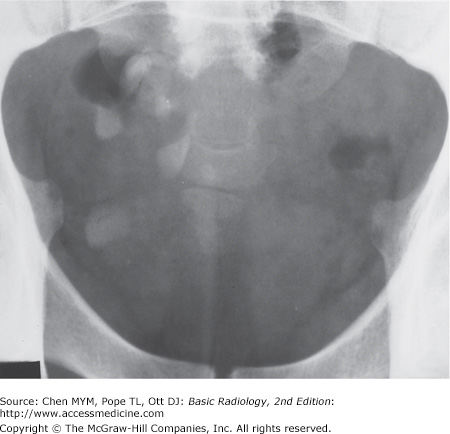

Figure 8-1.

(A) Normal plain film of the abdomen. The lower margins of the posterior portion of the liver, the hepatic angle (H), and the lower part of the spleen (S) are delineated by a fat shadow. Both kidneys (K) and the psoas muscle shadows (arrowheads) are outlined by a fat shadow. The properitoneal fat stripe is also shown bilaterally (arrows). (B) Diagram of normal abdominal plain film.

Organ enlargement can be recognized by the effect of displacement on nearby bowel loops or by obliteration of the adjacent normal fat or gas pattern. Hepatomegaly may compress the proximal transverse colon below the right kidney. Splenomegaly may push the splenic flexure of the colon downward. A large fused renal shadow across the psoas muscle and lumbar spine suggests a horseshoe kidney.

Fat density, which is between that of soft tissue and that of gas, outlines the contour of solid organs or muscles. In obese patients, fat may not be distinguishable from ascitic fluid on plain abdominal film. The flank stripe, also called the properitoneal fat stripe, is a line of fat next to the muscle of the lateral abdominal wall (see Figure 8-1). The flank stripes are symmetrically concave or slightly convex in obese people and are located along the side of the abdominal wall. The normal properitoneal fat stripe is in close proximity to the gas pattern seen in the ascending or descending colon. Widening of the distance between the properitoneal fat stripe and the ascending or descending colon suggests fluid, such as abscess, ascitic fluid, or blood within the paracolic gutter.

Fat is present in the retroperitoneal space adjacent to the psoas muscle (see Figure 8-1). The psoas muscle shadow may be absent unilaterally or bilaterally as a normal variant or as a result of inflammation, hemorrhage, or neoplasms of the retroperitoneum. Unilateral convexity of the psoas muscle contour suggests an intramuscular mass or abscess. The quadratus lumborum muscles may be delineated by fat located lateral to the psoas shadow (see Figure 8-1). In the pelvis, the fatty envelope of the obturator internus muscle is seen on the inner aspect of the pelvic inlet (see Figure 8-1). The dome of the urinary bladder may be delineated by fat.

Gas has the lowest density (radiolucency) in the abdomen. It is seen in the stomach and colon, but it is rarely seen in the normal small bowel because the air rapidly traverses the organ. Presence of more than a minimal amount of gas in the small bowel should be considered abnormal and is indicative of a functional ileus or mechanical obstruction. Identification of the differences between the gas shadows of the jejunum, ileum, or colon helps to assess the location of bowel obstruction (Figure 8-2). A gas pattern in distended intestinal loops is usually limited above the point of mechanical obstruction, but functional ileus has a more diffuse distribution in both the small intestine and the colon. If the gas shadow in the intestine is displaced to an unusual location, a soft-tissue mass, either inflammatory or neoplastic, may be suspected. The presence of air-fluid levels in a distended small intestine on upright films suggests either functional ileus or mechanical obstruction. Fluid levels within the stomach or colon are ordinarily of no pathologic importance, because fluid may be introduced by oral agents or by cleansing enemas. The presence of solid material with a mottled appearance and small bubbles of gas surrounded by the colonic contour suggests feces in the colon.

A large amount of gas seen in the peritoneal cavity indicates postoperative status or bowel perforation. Air bubbles in the peritoneal cavity indicate a perforated viscus, abscess, or necrotic tumor. In the right upper quadrant, air that is seen in the biliary tree or around the gallbladder suggests cholecystoenteric fistula or emphysematous cholecystitis. A finely arborizing gas pattern over the right upper quadrant that extends peripherally to the edge of the liver is characteristic of hepatic portal vein gas. In the bowel wall, multiple air bubbles may indicate pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. Extraluminal gas also may appear within the retroperitoneal structures, including the lesser omental bursa, a subhepatic site, the paraduodenal fossa, and the pericecal or periappendiceal areas. A gas pattern seen below the bony pelvis indicates an inguinal or femoral hernia.

Bony structures or calcifications have the highest density (radiopacity) that is seen on the plain film. Bony structures comprise the ribs superiorly, the lumbar spine, and the pelvis. Calcifications in the abdomen include calcified arteries, calculi in the urinary or biliary tract, prostatic calculi, pancreatic calcifications (which are usually indicative of chronic pancreatitis, with or without carcinoma), appendicolith, or ectopic gallstone in the small bowel associated with mechanical obstruction from gallstone ileus. Some foreign bodies, including ingested foreign bodies, bullets, or surgical clips, may be seen in the abdomen. Other rare structures, such as parasitic, metastatic, or heterotopic bone formations, also may be seen in the abdomen.

Suspicion of urinary calculi is a indication for abdominal radiography. About one-half of calculi in the urinary tract that are shown on unenhanced helical CT can be detected on plain abdominal films. On the other hand, about 15% of gallstones are radiopaque and are seen on abdominal plain radiograph. Ultrasonography is the better choice in evaluating gallstones.

Technique Selection

The routine abdominal films consist of supine and upright views. If the patient cannot stand for an erect abdominal film and a PA view of the chest, the cross-table lateral projection with the right side elevated may be used to assess pneumoperitoneum and air-fluid levels. As little as 1 to 2 mL of free air in the peritoneal space may be identified if the films are appropriately obtained. The PA view of the chest is usually obtained as part of an acute abdominal series because an abnormality in the chest may have symptoms referred to the abdomen. Oblique views of the abdomen may be obtained, if needed.

Plain abdominal radiography is less sensitive in evaluating solid organs or metastases. In recent years, increased use of cross-sectional techniques, such as ultrasonography and CT, has shown them to be more sensitive in assessing disorders of the abdominal solid organs and metastatic diseases. Acute cholecystitis is better assessed by ultrasonography or nuclear medicine studies.

Exercise 8-1. Upper Abdominal Calcifications

Adrenal calcification.

Calcified hepatic metastases.

Pancreatic calcification.

Primary calcified mucoproducing adenocarcinoma in the colon.

Adrenal calcification

Calcified hepatic metastases

Pancreatic calcification

Primary calcified mucoproducing adenocarcinoma in the colon

8-1. This case demonstrates multiple faceted calcifications in the right upper quadrant that are characteristic for gallstones (B is the correct answer to Question 8-1).

8-2. This case shows three separate deposits of calcified density confined to the right renal shadow. The largest one measures 2 cm in greatest diameter (C is the correct answer to Question 8-2).

8-3. This case shows multiple stippled calcifications in the upper abdomen adjacent to the lumbar spine. In a patient with a history of alcoholism, pancreatic calcification from chronic pancreatitis would be the most likely diagnosis (C is the correct answer to Question 8-3).

8-4. This case shows stippled and discrete calcifications overlying the right twelfth rib, just above the renal outline. When calcification in the lung base, skin, retroperitoneum, pancreas, kidney, and adrenal glands is excluded, hepatic calcification should be considered in a patient with a history of colon cancer (B is the correct answer to Question 8-4).

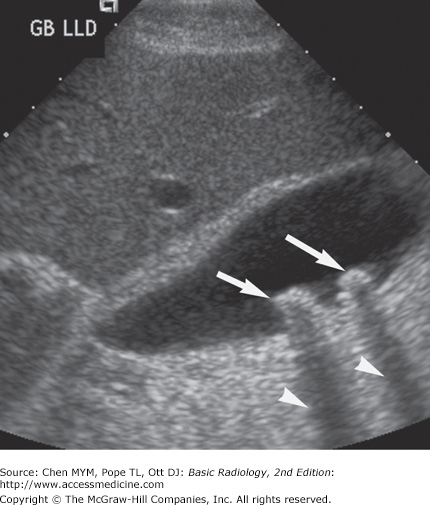

About 15% to 20% of gallstones are calcified sufficiently to be seen on plain abdominal film. Most gallstones comprise mixed components, including cholesterol, bile salts, and biliary pigments. Pure cholesterol and pure pigment stones are uncommon. Calcified gallstones vary in size and shape. Most gallstones have thin, marginal calcification with central lucency and are laminated, faceted, or irregular in shape. Some gallstones contain gas in their fissures, whether calcified or noncalcified. Milk-of-calcium or “limy” bile occurs in patients with long-standing cystic duct obstruction. The bile contains a high concentration of calcium carbonate and is densely radiopaque on plain radiograph (Figure 8-7). Calcification of the gallbladder wall (porcelain gallbladder) develops in patients with chronic cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, and cystic duct obstruction. Porcelain gallbladder is characterized by curvilinear calcification in the muscular layer of the gallbladder mimicking a calcified cyst (Figure 8-8). In general, ultrasonography is the primary modality now used to evaluate the gallbladder (Figure 8-9).

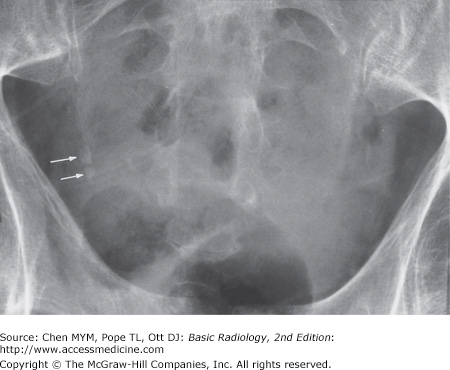

Nephrolithiasis is the most common cause of calcification within the kidneys. Most renal calculi (85%) contain calcium complexed with oxalate and phosphate salts. Any process that creates urinary tract stasis may cause the development of urinary calculi. Renal calculi are usually small and lie within the pelvicalyceal system or in a calyceal diverticulum. They may remain and increase in size, or they may pass distally. When calcifications are seen projecting over the renal shadows on routine films of the abdomen, an oblique view may be obtained to localize the densities in relation to the kidneys. A staghorn calculus contains calcium mixed with magnesium, ammonium, and phosphate and forms in the environment of recurrent urinary tract infection with alkaline urine. CT is more sensitive than plain radiography in evaluating urinary calculi.

The adrenal gland is located at the superomedial part of the adjacent kidney. The right gland is lower than the left. Normally the adrenal gland measures less than 2.5 × 3 cm. Stippled, mottled, discrete, or homogeneous calcifications may appear as a portion of the adrenal gland or may occupy the entire organ, forming a triangular clump in the adrenal glands (Figure 8-10). Most adrenal calcifications are incidental findings in normal-sized glands. They are caused by neonatal adrenal hemorrhage, prolonged hypoxia, severe neonatal infection, or birth trauma. Less than one-fourth of patients with Addison’s disease have adrenal calcifications.

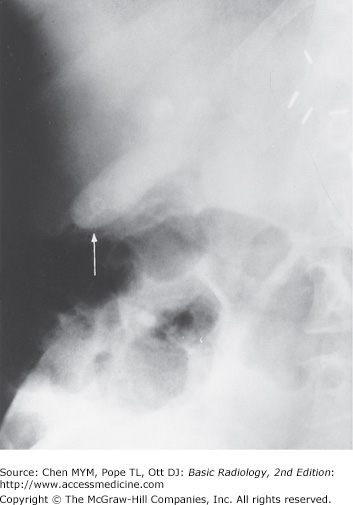

Figure 8-10.

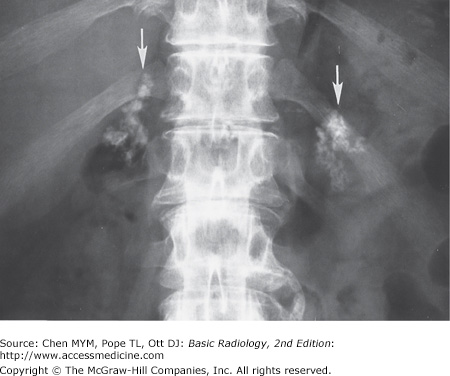

Solid adrenal calcifications. Bilateral discrete, stippled adrenal calcifications (arrows) in the normal-sized glands in an asymptomatic patient with a history of complicated childbirth (From Chen MY et al: Abnormal calcification on plain radiographs of the abdomen, The Radiologist 1999;7:65-83, used with permission).

In the United States, 85% to 90% of patients with pancreatic lithiasis are alcoholics. Conversely, less than half of patients with chronic pancreatitis ever develop pancreatic calcifications visible on plain radiograph. Although gallstones passing through the biliary tract can cause acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic calcification is rarely caused by cholelithiasis.

Hepatic calcifications are caused primarily by neoplasms, infections, or parasitic infestations. Primary hepatic tumors, both benign and malignant, may have calcifications. Colonic carcinoma and papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary are the most frequent primary tumors causing calcified metastases in the liver. Other primary neoplasms in the thyroid gland, lung, pancreas, adrenal gland, stomach, kidney, and breast may cause calcified hepatic metastases. Inflammatory calcified granulomas related to tuberculosis or histoplasmosis are common in miliary calcifications. Calcified cystic lesions, such as Echinococcus disease in the liver, are commonly seen in areas of the world where the causative organism is endemic.

Exercises 8-2. Pelvic Calcifications

Calcified ovarian tumor

Multiple phleboliths

Multiple ureteral calculi

Uterine fibroid calcification

Bladder calculus

Chondrosarcoma of the sacrum

Cystadenoma of the ovary

Uterine fibroid calcifications

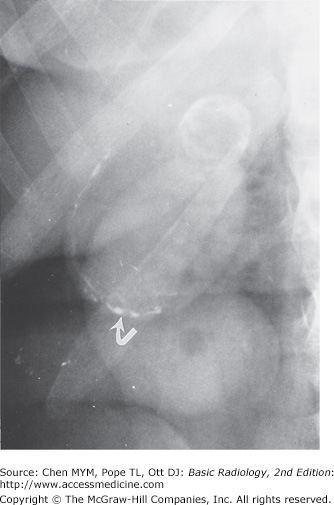

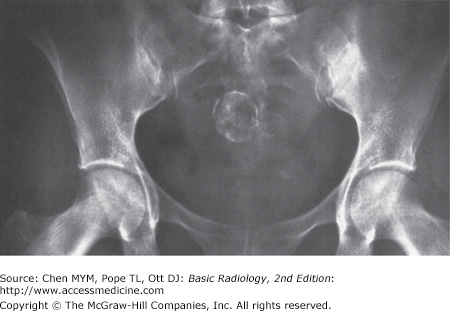

8-5. This case is that of a boy with acute appendicitis (A is the correct answer to Question 8-5). An oval calcification measuring 0.8 cm in diameter projects over the iliac bone and laterally to the right sacroiliac joint with a distended appendiceal lumen filled with gas. At surgery, gangrenous appendicitis with perforation and an obstructing appendicolith were found.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree