Compartmental Anatomy and Biopsy Planning

The radiologic staging of a soft tissue tumor is a vital part of a patient’s evaluation (1, 2). As previously noted in Chapter 3, accurate staging is essential to determine appropriate clinical treatment and prognosis. Complete staging typically requires information that is not available at the time of initial patient presentation, such as tumor grade and presence or absence of metastases. The local extent of disease, however, is a critical part of tumor staging and is accurately defined with magnetic resonance (MR) imaging at initial patient presentation (2). Inherent in the determination of local extent of disease for staging is the concept of anatomic compartments.

Anatomic compartments are defined by natural barriers that prevent the spread of tumor (3). These barriers include major fascial septa, periosteum, cortical bone, joint articular cartilage, and joint capsules (3). Lesions that are confined to a specific anatomic space defined by these barriers are considered to be intracompartmental. This designation has clinical implications in that intracompartmental lesions are lower stage than similar grade extracompartmental lesions; therefore, they generally have an improved prognosis. Extracompartmental lesions are those that have spread beyond the boundaries of the compartment of origin. Mechanisms of extracompartmental spread include direct tumor extension, contamination from hemorrhage, or inappropriate open or percutaneous biopsy (3, 4).

Accurate delineation of the local tumor extent and compartmental status is essential, not only in local staging, but also in planning definitive surgery and in planning surgical or percutaneous biopsy. As a general rule, image-guided biopsy is usually done using the shortest path between the skin and the lesion, avoiding vital structures such as vessels and nerves (3). The biopsy of musculoskeletal lesions and specifically soft tissue tumors, however, has additional requirements. It is essential that the biopsy needle path does not violate any uninvolved compartment, neurovascular structure, or joint (3), and that the biopsy path coincides with that of the planned surgical incision (5). Definitive surgery includes complete removal of the biopsy needle tract, which is considered to be contaminated tissue, and consequently, the biopsy needle tract should ideally be made along the same path as the incision for definitive surgery (3).

As radiologists, we are often called on to perform imageguided biopsies. To ensure optimum patient care, biopsy of a soft tissue tumor should never be undertaken without prior consultation with the surgeon who will perform the definitive surgery (6, 7). Accordingly, percutaneous biopsy should be planned as carefully as the definitive surgery (6). In a 1982 landmark study, Mankin et al. surveyed members of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society and reported the accuracy of diagnosis and incidence of complications associated with biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors (6). This study of 329 patients noted that the optimum treatment plan had to be altered as a result of biopsy-related problems in 8.2% of patients, unnecessary amputation was performed as a result of problems with biopsy in 4.5%, and the patient prognosis and treatment outcome were adversely affected in 8.5%. A similar study was performed in 1992 involving 597 patients and showed almost identical results (8). Although these studies did not specifically address percutaneous image guided biopsies and were done prior to the availability of current sophisticated techniques, they served as a poignant reminder of the potential harm of inappropriate biopsy, such as violating compartmental anatomy or crossing tissue planes that may compromise subsequent definitive surgery.

This chapter reviews the anatomic compartments of the musculoskeletal system and the basic principles for musculoskeletal tumor percutaneous biopsy. This knowledge is required for the local staging of soft tissue tumors and for the planning and performing of percutaneous image-guided biopsy.

COMPARTMENTAL ANATOMY

General Principles

As noted above, anatomic compartments are confined anatomic spaces that can provide natural barriers to tumor extension. The Enneking tumor surgical system

(Table 3.5), the system adopted by the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society and the system most commonly used in the assessment of musculoskeletal tumors, utilizes the local tumor extent in determining tumor stage. The considerations for determining the local tumor extent mirror those defined for tumor compartmental localization.

(Table 3.5), the system adopted by the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society and the system most commonly used in the assessment of musculoskeletal tumors, utilizes the local tumor extent in determining tumor stage. The considerations for determining the local tumor extent mirror those defined for tumor compartmental localization.

Fundamental concepts relevant to compartmental anatomy are described below.

KEY CONCEPTS

Anatomic compartments are defined by natural barriers that prevent the spread of tumor.

These barriers include major fascial septa, periosteum, cortical bone, joint articular cartilage, and joint capsules.

Intracompartmental lesions are those that are confined to the compartment of origin.

Extracompartmental lesions are those that have spread beyond the boundaries of the compartment of origin.

Skin and subcutaneous fat: The skin and subcutaneous fat contain no barriers to tumor spread and therefore are considered to be a single compartment. They are separated from the deeper structures by thick fascia that forms a natural barrier to tumor extension (3, 9).

Muscle: A lesion confined to a single muscle is intracompartmental. A lesion that extends beyond the muscle of origin, however, may still be intracompartmental if it does not violate the barriers defined for that specific anatomic location (3). Hence, tumors within muscular compartments composed of more than one muscle (such as the thigh) are still considered intracompartmental even if multiple muscles are involved, as long as the lesion remains within the boundaries of the compartment (9).

Joint: Each joint is considered to be a distinct compartment (3).

Bone: Each bone is considered to be a distinct compartment. The space between the bone and the adjacent soft tissue is termed the parosseous tissue, and is also considered to be a compartment (3). The parosseous compartment is a potential compartment between the bone and the overlying muscle (9). Lesions on the surface of bone that have not invaded the bone or the overlying muscle are considered to be intracompartmental (9).

Vessels and nerves: Neurovascular structures are not considered to be specific compartments, but they may be a path of tumor spread (3). As such, they must be specifically addressed during staging and biopsy planning.

Specific Compartments

Specific compartments relevant to local tumor staging are defined and illustrated below.

Upper Extremity

Upper Arm

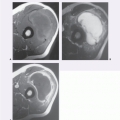

The soft tissues of the upper arm are divided into two compartments: anterior and posterior (Fig. 14.1) (8, 10). Other compartments associated with the upper arm include the periscapular compartment (infraspinatus, teres minor, and rhomboid muscles) and the supraspinatus and deltoid compartments. The supraspinatus and deltoid muscles each are their own separate compartments (3).

Anterior compartment: Biceps (long and short heads), brachialis, coracobrachialis, and brachioradialis muscles.

Posterior compartment: Triceps muscle.

Periscapular compartment: Infraspinatus, teres minor, and rhomboid muscles.

Supraspinatus and deltoid compartments: Supraspinatus and deltoid muscles, respectively.

Forearm

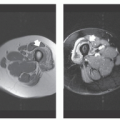

The forearm is divided into two, three, or four compartments (10). In the two-compartment model, the forearm is divided into flexor (volar) and extensor (dorsal) compartments. The four-compartment model further divides each of these compartments into a superficial and deep portion. The three-compartment model, presented below, is better adapted to surgical anatomy and commonly used by surgeons (10, 11). This divides the forearm into the volar, dorsal, and lateral compartments, with the lateral compartment also termed the mobile wad or mobile wad of Henry (Fig. 14.2) (12).

Volar compartment: The muscles of the volar compartment are further subdivided into deep and superficial groups (12). The deep group consists of the flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and the

pronator quadratus muscles. The superficial group includes the flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, and pronator teres (12).

pronator quadratus muscles. The superficial group includes the flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, and pronator teres (12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree