specificity; therefore, they will cross-react with nuclei from different sources. The primary sources for study of these antibodies are patients with SLE and related systemic rheumatic diseases. Many studies have centered on defining the specificity of these antibodies and have contributed extensively to our understanding of their immunopathologic role in connective tissue disorders. It is worthwhile to state that 100% of patients with SLE are ANA positive; the concept of ANA-negative lupus is no longer valid. Furthermore, autoantibodies against small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP), also known as anti-Smith antibodies, were found to be highly specific for SLE, although they are present in only 15% to 30% of SLE patients. They are present more frequently (about 60%) in young black women with SLE. The immunobiology of lupus is well beyond the scope of this text, but we have to emphasize that despite exhaustive studies of tolerance and the existence of mouse model of lupus, there have not been any clinically significant advances in the specific treatment of SLE in nearly two decades.

Table 8.1 CLINICAL AND IMAGING HALLMARKS OF CONNECTIVE TISSUE ARTHRITIDES (ARTHROPATHIES) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

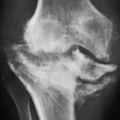

and/or accompanied by articular erosions (Fig. 8.3). Some patients present with sclerosis of the distal phalanges (acral sclerosis) (Fig. 8.4) or with resorption of the terminal tufts (acroosteolysis). Osteonecrosis, which is frequently seen, has been attributed to complications of treatment with corticosteroids (Fig. 8.5). However, current investigations suggest the vital role of the inflammatory process (vasculitis) in the development of this complication.

anticentromere. Recently, researchers have identified a new genetic link to systemic form of scleroderma, a susceptibility locus involving the genome CD247 (that encodes the T-cell receptor zeta subunit modulating T-cell activation), in addition to previously known genes MHC, IRF5, and STAT4 (that encodes a regulatory protein important to immune system). However, these linkages are weak and do not provide a clear-cut genetic tool that is useful for patients. Clinically, many patients develop joint involvement, which is manifesting as arthralgia and arthropathy leading to flexion contractions of the fingers. Most patients have the so-called CREST syndrome, which refers to the coexistence of calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon (episodes of intermittent pallor of the fingers and toes on exposure to cold, secondary to vasoconstriction of the small blood vessels), esophageal abnormalities (dilatation and hypoperistalsis), sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia; 30% to 40% of patients have a positive serologic test for rheumatoid factor and a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test.

calcifications within the upper and lower limbs can occasionally be quite prominent (see Figs. 8.8 and 8.9B, C). Corroborative findings are seen in the gastrointestinal tract, where dilatation of the esophagus and small bowel, together with a pseudo-obstruction pattern, is characteristic (Fig. 8.11). Pseudodiverticula in the colon are also commonly seen.

Figure 8.6 ▪ Scleroderma. A: A 24-year-old woman presented with atrophy of the soft tissues at the distal phalanges of the index, middle, and ring fingers (arrows). B: A radiograph of the fingers of the left hand of a 36-year-old woman shows atrophy of the soft tissue at the tip of the index and middle fingers (arrows) and early resorption of the terminal tufts (arrowheads). Compare with normal ring finger.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|