Ultrasound is an important modality to assess pediatric patients and uses continue to increase. In this review, several emerging applications of ultrasound in pediatric patients are detailed, focusing on diseases impacting infants, including necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation with midgut volvulus, and liver lesion characterization.

Key points

- •

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a potentially devastating disease of infants. In conjunction with radiographs, ultrasound of the bowel, mesentery and peritoneal cavity, and abdominal wall may help in diagnosis and management.

- •

Ultrasound is increasingly important in the diagnosis of malrotation with midgut volvulus, with findings including proximal duodenal dilation and clockwise swirling of bowel and mesentery around the superior mesenteric artery.

- •

Liver lesions in infants are different from those found in older patients. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is increasingly used for definitive characterization due to the specific appearance of different lesions.

Video content accompanies this article at http://www.radiologic.theclinics.com .

Introduction

Ultrasound is an important modality for the assessment of pediatric patients and the number of clinical uses continues to increase. In this review, several emerging applications of ultrasound in pediatric patients are detailed, focusing on diseases impacting infants, including necrotizing enterocolitis, malrotation with midgut volvulus, and liver lesion characterization.

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Background

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a gastrointestinal emergency in newborns and is potentially a devastating disease. Most cases occur in very low birth weight (<1500 g) infants born at less than 32 weeks’ gestation, but it is important to note that NEC can occur in term infants, particularly those who have experienced an ischemic event, such as patients with congenital heart disease. The true incidence of NEC is unknown; however, estimates range from 1 to 3 cases per 1000 live births or up to 7% of infants with birth weight between 500 and 1500 g, and death rates are reported to be as high as 50%. , There is substantial long-term morbidity in survivors of NEC, who often require prolonged hospitalization and suffer from continued intestinal, neurodevelopmental, and growth complications of the disease.

NEC is an evolving process of unknown but likely multifactorial etiology, characterized by ischemic necrosis of the intestinal mucosa and severe inflammation, which leads to an extension of enteric gas-forming bacteria into the bowel wall and into the portal venous system or may cause intestinal perforation. NEC most commonly affects the terminal ileum and proximal colon.

Treatment of NEC involves bowel rest with parenteral feeds, gastric decompression, antibiotic therapy, fluid replacement, and close monitoring to ensure surgical intervention is not required. Evidence of bowel perforation is currently the only widely accepted indication for surgical intervention. Acute complications of NEC include sepsis, cardiorespiratory failure, prolonged hospitalization, and death. Long-term complications include postischemic stricture formation, altered bowel motility, adhesions that may lead to bowel obstructions, and short bowel syndrome and/or intestinal failure as a result of resection of involved bowel segments.

The clinical presentation includes feeding intolerance, abdominal distention, abdominal discoloration, bloody stools, and vital sign instability; however, these signs may be very subtle and are not specific for NEC. , Therefore, imaging often plays a crucial role in the assessment of infants with concern for possible NEC.

Diagnostic Performance of Ultrasound

Radiographs have traditionally been the mainstay to assess infants with clinical concern for NEC. Sequential evaluation of the bowel gas pattern and appearance overtime may be helpful. Dilated and elongated bowel loops raise concern on radiographs for NEC, with a fixed loop of bowel (a bowel loop that does not change in appearance overtime on radiographs) additionally concerning. Intramural gas (pneumatosis intestinalis or coli), portal venous gas, and pneumoperitoneum may also be seen in association with NEC but are not specific for NEC. , , Importantly, the most common clinical staging system, the modified Bell staging, uses radiographs as part of the staging criteria.

Ultrasound is gaining acceptance by neonatologists and pediatric surgeons and is currently predominantly used in conjunction with radiographs to assist in the clinical diagnosis, management, and follow-up of infants at risk for NEC. Faingold and colleagues demonstrated that the absence of bowel wall perfusion at color Doppler ultrasound (US) is more sensitive and specific than the presence of free air at abdominal radiography in the detection of necrotic bowel in NEC. Color Doppler US findings were also shown to be more accurate than the Bell staging and abdominal radiography in the prediction of necrosis in neonates with NEC and therefore may alter clinical staging and management.

Cuna and colleagues evaluated ultrasound findings compared to patient outcomes in a meta-analysis and demonstrated an association of focal fluid collections, complex ascites, absent bowel peristalsis, pneumoperitoneum, bowel dilation, bowel wall absent perfusion, or bowel wall thinning, thickening, or abnormal echogenicity were all associated with poorer outcomes, specifically death and surgery requirement. Infants with NEC requiring surgical management have also been shown to have worse outcomes. Conversely, when portal venous gas, pneumatosis intestinalis, increased bowel wall perfusion, and simple ascites were independently compared with the need for surgery or death, there was no significant association.

Finally, Le Cacheux and colleagues reported an association of mesenteric thickening, hyperechogenicity of intraluminal bowel content, edema and hyperemia of the abdominal wall, and poor intestinal wall definition that are also associated with poorer patient outcomes, including patient death and short-term or long-term surgery requirement.

Patient Preparation

Patients with clinical concern for NEC will typically be cared for in the neonatal intensive care unit, and examinations are performed portably. No specific patient preparation is needed; however, patients are often fasting for treatment of suspected NEC.

Ultrasound Scanning Protocol

Comparison with preceding radiographs may be helpful to focus on specific areas of concern. A small footprint curved array (microconvex) mid-frequency (4–10 MHz) transducer is useful to assess the abdomen with a larger field of view for an overall assessment, to scan beneath ribs and the xyphoid, and to compress gas away from areas of interest. This should be followed by a linear high-frequency (6–20 MHz) transducer to assess structures in greater detail and for Doppler evaluation. Some authors advocate for an “outside-to-in” imaging approach moving from the colon to the small bowel, while others prefer to trace the course of bowel, followed by quadrant assessment. The structures to be evaluated are detailed in Table 1 . Both still and cinematic “cine” images should be saved if possible, including cinematic images with the transducer stationary to evaluate for bowel peristalsis. A shortened protocol can be considered for specific problem-solving, in limited resource settings, or for follow-up examinations.

| Structure | Findings Assessed | |

|---|---|---|

| Grayscale Assessment | Abdominal wall | Edema |

| Peritoneal cavity | Free fluid Septated fluid Debris-containing fluid Focal fluid collection(s) Pneumoperitoneum | |

| Bowel wall | Thickening (>3 mm) Thinning (<1 mm) Peristalsis | |

| Bowel lumen | Dilation Hyperechoic contents | |

| Mesentery | Thickening | |

| Portal vein branches | Gas | |

| Color or Power Doppler Assessment | Abdominal wall | Hyperemia |

| Bowel wall | Hyperemia Hypoperfusion No perfusion | |

| Mesentery | Hyperemia | |

| Portal vein branches | Gas Spectral Doppler may be helpful to distinguish gas from rouleaux formation |

Ultrasound Findings

Abdominal wall

NEC causes abdominal wall edema and hyperemia, usually following the distribution of the diseased bowel. Abdominal wall edema is seen sonographically as thickening and increased echogenicity, progressing to reticular strands of fluid separating the subcutaneous tissues resembling a mosaic pattern of fluid and fat. Hyperemia is also a common finding and is best assessed with the linear probe.

Peritoneal cavity

The entire peritoneal cavity should be assessed, most often by dividing the abdomen into 4 quadrants and carefully evaluating each quadrant. Septated fluid, debris-containing fluid, and focal fluid collections are associated with poorer outcomes in NEC. Evaluation of fluid should include an attempt to visualize linear echogenic foci, turbid, or punctate echoes (debris) within abdominal cavity fluid. Focal fluid collections may closely approximate and mold to the shape of a loop of the bowel or may be located within thickened mesentery, making distinction among bowel wall, mesentery, and fluid collection challenging, particularly for echogenic fluid. Lack of color Doppler signal can be helpful for diagnosing fluid. A complex collection adjacent to an avascular or otherwise abnormal-appearing bowel loop (see Bowel section) should raise concern for bowel perforation. Pneumoperitoneum, even in small quantities, can be readily visualized at ultrasound, and its presence suggests bowel perforation.

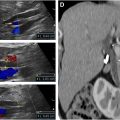

Mesentery

Normally, the mesentery in infants is a thin structure and is inconspicuous at ultrasound. When visible, the normal appearance is a fine hypoechoic structure softly laced between small bowels. Abnormal mesentery in the setting of NEC is thickened, hyperechoic or heterogeneous, and hypervascular, with at times a mass-like appearance, causing splaying of bowel loops ( Fig. 1 ). In later stages of NEC, the mesentery becomes fingerlike or bandlike, with spongiform projections causing tethering of bowel loops.

Bowel

Bowel peristalsis

Normal small bowel will demonstrate normal peristalsis, defined as at least 10 contractions per minute. Peristalsis may be decreased or absent in the setting of NEC. However, caution should be used in patients treated by paralytic agents that may impact bowel peristalsis.

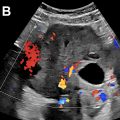

Bowel wall echogenicity, distinction, thickness, and perfusion

Normal bowel wall will have a stratified appearance of bowel wall layers (also called gut signature) and measures about 1.7 mm in thickness. Bowel wall of loops affected by NEC may have a loss of the normal distinction between bowel wall layers, have a general poorly defined appearance, and/or demonstrate increased echogenicity. Bowel wall thickening (thickness >3 mm) or thinning (thickness <1 mm) may be seen. With increased disease severity, thick hyperemic bowel progresses to thin avascular bowel prior to possible perforation ( Fig. 2 ). Hyperemia is defined as striated (“zebra” appearance), complete ring of bowel wall flow, and/or Y-shaped flow related to distal mesenteric and subserosal vessel flow.

Bowel content

Intraluminal content of the bowel normally is fluid and air. Intraluminal content is considered abnormal when the echogenicity is greater than the adjacent intestinal wall, liver, and spleen. The proposed etiology is that bowel impacted by NEC contains sloughed mucosa, muscle, and submucosa layers, as well as mucin, hemorrhage, and inflammatory debris ( Fig. 3 ). Care should be taken not to confuse intraluminal milk or formula content with the abnormal content of NEC.

Bowel wall pneumatosis

Pneumatosis is nonspecific and is not always seen in the setting of NEC, and the severity does not correlate with disease severity. Therefore, although ultrasound performed for NEC should include assessment for pneumatosis, interpretation should be made in conjunction with clinical context and with incorporation of all sonographic findings. Air within bowel wall will be visible as echogenic foci or a complete bright rim in both the nondependent and dependent portions of the bowel wall ( Fig. 4 ). Evaluating the deep wall of bowel is helpful to ensure air is truly air located within bowel wall, rather than small foci of air located within the projections of the valvulae conniventes, which is a normal finding. Assessing the appearance of the bowel wall with transducer held stationary while the underlying bowel peristalses can also be helpful to distinguish intraluminal air from intramural air, because pneumatosis will remain in a fixed position within the bowel wall, while intraluminal content will move.