Evaluating Women With Lumps, Thickening, Discharge, or Pain: Imaging Women With Signs or Symptoms That Might Indicate Breast Cancer

Despite the heavy emphasis (particularly in the legal system) on the prompt evaluation of women who have signs or symptoms that might indicate breast cancer, there are no data to show that earlier intervention for these women has any influence on the long-term outcome should they be found to have breast cancer. The only data that show a decrease in breast cancer mortality are related to the detection of some cancers by screening mammography before there is any clinical evidence of the disease. Nevertheless, because of the great psychological issues surrounding breast cancer and the medical/legal pressures, we spend a great deal of effort evaluating women who have signs or symptoms.

The most common signs and symptoms for which women are referred to our practice are a lump, area of thickening, area of pain, non-bloody nipple discharge, and a bloody nipple discharge. Aiello et al found that an actual lump was the only clinical finding that had any major association with breast cancer (1). My own experience (anecdotal) is that in many cases, the woman who presents with a lump or thickening actually went to her doctor because she felt a pain or soreness in her breast and, as a consequence, carefully felt the area for the first time. The soreness made her suspect that the normal tissue “lumpiness” was abnormal, causing her to be concerned. Many women who come to us with the complaint of a lump have nothing more than focal soreness and normal breast tissue.

This recurrent theme is due to the fact that many women

still believe that pain in the breast is an indication of cancer. Education around this topic is greatly needed. I suspect that if women learned to ignore breast pain and soreness, attendance at breast clinics could be greatly reduced, along with referrals for breast imaging. We have not studied the problem specifically, but based on over 30 years of experience, imaging never provides an explanation for breast pain unless there is a true lump that represents a distended cyst or abscess. There are a handful of breast cancers that I have seen in the 30 years that were associated with pain. It is unclear whether these were actually causing the pain; I suspect that most were coincidental, since breast pain is so common. I have seen a few cancers that were associated with a “drawing” sensation, as if something were pulling from within the breast (not surprising, given the cicatrization that cancers produce). When pressed, these women admitted that they called it a pain, but it did not really hurt. They chose the term “pain” because this was the best word that they could find to describe the sensation.

still believe that pain in the breast is an indication of cancer. Education around this topic is greatly needed. I suspect that if women learned to ignore breast pain and soreness, attendance at breast clinics could be greatly reduced, along with referrals for breast imaging. We have not studied the problem specifically, but based on over 30 years of experience, imaging never provides an explanation for breast pain unless there is a true lump that represents a distended cyst or abscess. There are a handful of breast cancers that I have seen in the 30 years that were associated with pain. It is unclear whether these were actually causing the pain; I suspect that most were coincidental, since breast pain is so common. I have seen a few cancers that were associated with a “drawing” sensation, as if something were pulling from within the breast (not surprising, given the cicatrization that cancers produce). When pressed, these women admitted that they called it a pain, but it did not really hurt. They chose the term “pain” because this was the best word that they could find to describe the sensation.

My experience is that breast pain should cease to be a reason for imaging referral. Periodic breast pain associated with the menstrual cycle is almost ubiquitous. It is also likely that some focal breast pain is actually referred chest wall pain. One of my surgical colleagues felt that as much as 50% of what patients felt was breast pain was actually a chest wall disorder such as costochondritis. The distinction can be made by seeing whether the pain is caused by squeezing the breast from side to side as opposed to back against the chest wall. Clearly, if the pain is caused by pushing the breast against the chest wall but not from squeezing it side to side, then it is likely chest wall pain and not breast pain. Breast pain should be treated clinically and symptomatically. Beyond routine screening, we should discourage imaging referrals for “pain.”

I have found that it is frequently difficult to distinguish between a “lump” and “thickening.” Since clinical examination is almost completely a subjective art, there is a large overlap. One examiner’s lump may be another’s thickening and still a third’s normal breast tissue. I have been told repeatedly over the years by numerous women that they do not examine themselves because their breasts are too lumpy and they “cannot tell one from the other.” I think we have made a mistake in telling women that they should be trying to tell one from the other. What I now tell patients is that the breast is a “lumpy” organ; that is the way it is constructed. The lumps, however, are always in the same place and do not move from one month to the next. I believe that we should encourage women not to be diagnosticians, but rather to carefully examine themselves and to learn where their lumps are. Breast self-examination should be done not to tell one lump from the other, but to find the new lump should it develop, and to bring that one to their doctor’s attention. It should be reinforced that pain is “not much fun,” but it should not cause fear since it is almost never due to breast cancer.

Breast cancer can cause a nonspecific hardening or thickening of the tissues in a portion of the breast. The most common reason for thickening, however, in my experience is normal breast tissue. I suspect that sometimes tissues become “thicker” because of the heterogeneous effects that hormones can have on different parts of the breast. This has been called a “differential end-organ response.” Most thickening is followed over several cycles and then dismissed. It is most common in the upper outer quadrant. Many women have what is almost certainly physiologic thickening in this area. There is often almost a ridge at the edge of the parenchyma just below the axilla. Despite the fact that thickening is usually physiologic, when a patient is referred for this, we evaluate the area in the same way that we evaluate the woman who is referred with a “lump.”

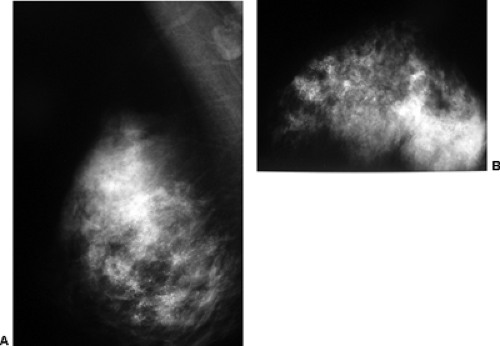

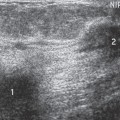

Nipple discharge is an elusive issue. There are numerous reasons for a nipple discharge, most of which are never explained. The discharging fluid can be from multiple ducts, or from a single duct. It can be unilateral or bilateral. Breast cancer can cause a discharge. It has been suggested that breast cancer causes a bloody discharge, but the majority of discharges are still due to benign causes, and some cancers can produce a serous discharge with no apparent blood. Anecdotally, it seems that breast cancers are now less likely to be the cause of a discharge than in the past. In a recent review of 395 patients evaluated for a nipple discharge, only 11 (3%) had an underlying malignancy, and several of these had Paget’s disease of the nipple. Perhaps this is due to earlier cancer detection by screening. I suspect that many discharges are physiologic and due to hormonal influences on the breast tissue. They can be associated with duct ectasia. Many are due to the presence of a benign, intraductal papilloma. The discharging fluid can be quite varied, ranging from white, to yellow, to green, brown, and gray. A truly clear discharge is very uncommon. Patients who have bilateral discharge or discharge from multiple ducts are almost always followed clinically with no surgical intervention. If the discharge comes from a single duct and it occurs spontaneously, this is usually investigated. We perform a mammogram to look for any focal lesion, in particular calcifications that could indicate an intraductal process (Fig. 21-1). Nevertheless, it is extremely rare to find anything on the mammogram to explain a discharge. Although some physicians request an ultrasound evaluation, there are not data to support the use of ultrasound to evaluate women with a discharge if there is nothing palpable on the clinical examination or visible on the mammogram.

The use of galactography (ductography) has been promoted over the years to assist in the evaluation of a discharging duct. The support for this procedure is purely anecdotal, and very few still perform the study. There have been an increased number of reports of using tiny endoscopes to look directly inside a discharging duct. The value of this “ductoscopy” remains to be demonstrated. If a discharge is of concern to the surgeon, he or she often will explore the problem in the operating room by cannulating

the duct using a sialogram probe and then doing a circumareolar incision to find it under the nipple and then dissect the duct and its branches back into the breast. I have been unable to find any cases in our institution where a cancer was missed using this approach. Nevertheless, it can result in the removal of a large segment of tissue, and a less invasive way to exclude breast cancer in these women would be desirable.

the duct using a sialogram probe and then doing a circumareolar incision to find it under the nipple and then dissect the duct and its branches back into the breast. I have been unable to find any cases in our institution where a cancer was missed using this approach. Nevertheless, it can result in the removal of a large segment of tissue, and a less invasive way to exclude breast cancer in these women would be desirable.

“Diagnostic” Mammography

Mammography is used routinely as a “diagnostic” test for the evaluation of clinically suspicious breast abnormalities. It is interesting that, objectively, this is its least important role, but through market pressures and the general trend toward image-guided care, the analysis of clinically detected abnormalities has become a major role for imaging.

The primary value of mammography is the earlier detection of breast cancer through the screening of asymptomatic women. In most cases, by the time a cancer becomes palpable, the potential benefit from mammography has passed. Frequently a palpable abnormality is not even evident on the mammogram, or it is visible but remains indeterminate. It is rare that a mammogram is “diagnostic” in the sense that a firm diagnosis can be made based on the mammographic evaluation (2). Despite the absence of any objective data to confirm the value of mammography as a diagnostic test for palpable abnormalities, there are still those who believe that they actually derive information from the mammogram that they feel alters clinical management. It is actually somewhat misguided to compare other tests to mammography for diagnostic accuracy, but there are those who still do. Houssami et al compared the diagnostic accuracy of mammography to ultrasound among women ages 25 to 55. Not surprisingly, they found that ultrasound was diagnostically more useful (3). This is obvious to anyone who images the breast, given the simple fact that ultrasound can make the diagnosis of a cyst when mammography can only delineate a mass and cannot differentiate a cystic mass from a solid one. Nevertheless, the authors felt they had made an important comparison. Looking at mammography in a more objective and realistic fashion provides a clearer picture.

The Clinical Value of Mammography for Symptomatic Patients

Many physicians fail to understand the role of mammography for the woman who presents with a sign or symptom that could represent breast cancer. Paradoxically, some clinicians have expressed a lack of belief in the value of mammography as a screening technique but insist that they would send a patient with a lump, thickening, or other suspicious clinical finding for “diagnostic” mammography. This attitude reveals a lack of understanding of the capability of mammography.

Critical Path and Outcome Analysis

The true value of a test is its influence on how the patient does (outcome). An analysis of various interventions and their outcome determines what is now the critical path (the best way to achieve the desired goal). These are not new concepts but merely restate two basic medical questions that should always be asked before a test is ordered: “Will the result of this test alter the care of the patient?” and “Will action based on the result of the next test benefit the patient?”

These same questions should be asked when evaluating the use of mammography or any other imaging technique or intervention as a diagnostic modality. The answers for the use of mammography in evaluating a palpable mass can be anticipated by reviewing the range of clinical situations listed below.

Assume that an abnormality is palpated. The clinical examination produces a certain level of concern. The woman then has a mammogram. There are several possible results from the mammogram:

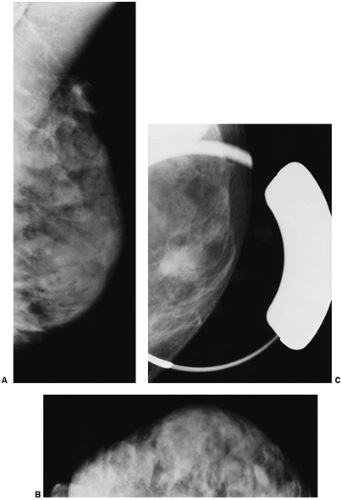

Scenario 1: The lump is visible on the mammogram and has the characteristics of a classically benign lesion, such as a fat-containing mass (lipoma, oil cyst, or hamartoma) or a calcified fibroadenoma (Fig. 21-2). This is one of the few situations in which the mammogram is actually diagnostic. These lesions have no significant malignant potential. When their mammographic appearance is typical and the mammographic finding corresponds to the clinical abnormality, they do not require biopsy or even further evaluation. In this situation, management is altered by the mammogram, and the patient benefits from the mammogram. This is one of the reasons for obtaining a mammogram to evaluate a palpable abnormality. Unfortunately, this is also an extremely rare occurrence.

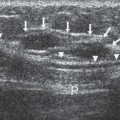

Scenario 2: The palpable lump is not visible on the mammogram (Fig. 21-3). It is well established that there are cancers that are evident on clinical breast examination but not visible on the mammogram; therefore, the clinician cannot rely on a negative mammogram to exclude a cancer. Thus, the clinician must still pursue a diagnosis, and management is not altered by the mammogram. This is a very common situation. The mammogram has not added to the diagnosis.

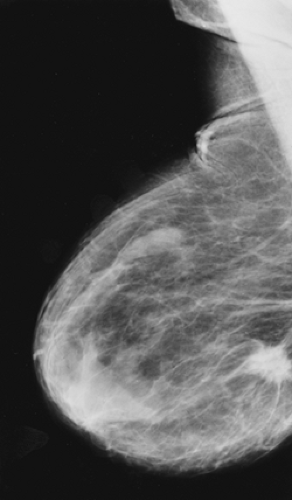

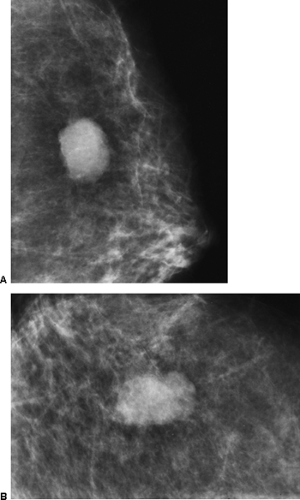

Scenario 3: The lump is visible on the mammogram, but its appearance is not specific (Fig. 21-4). The clinician must still pursue the diagnosis, and management is not altered by the mammogram. This is also fairly common.

Scenario 4: The lump is visible on the mammogram, and its morphologic characteristics are very suspicious for malignancy (Fig. 21-5). This often occurs when the lesion felt on clinical examination is actually cancer. Because these lesions are almost always very suspicious on the clinical examination alone, the mammogram rarely alters management. It is possible, however, that without the additional mammographic evidence, the clinician might have decided that his or her clinical suspicion was not sufficiently high to pursue a tissue diagnosis. If this is the case, then the mammogram could have resulted in earlier intervention and management would be altered. The frequency, however, of this particular scenario has never been documented scientifically, and in our experience it is very uncommon. Usually when a palpable mass has mammographic features that strongly suggest cancer, the clinical examination is highly suspicious and a biopsy would have been performed on the basis of the clinical findings regardless of the mammographic features. Basic management is not altered by the mammogram.

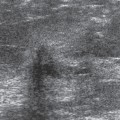

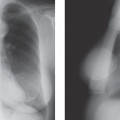

Figure 21-4 The palpable mass is visible on the mammogram, but its morphology is nonspecific. This mass is irregular in shape with a microlobulated margin on the MLO (A) and CC projections (B). Its morphology was also nonspecific on ultrasound (see Fig. 21-15). It proved to be a cyst. |

The preceding lists the range of possibilities when mammography is used to evaluate women with possible breast cancer. It is frequently forgotten that the only efficacious reason for performing mammography is to reduce the death rate from breast cancer by detecting cancers earlier. There are no studies that prove that its use in evaluating palpable abnormalities has any influence on mortality, which is the most important measure of outcome. An objective evaluation indicates the fact that mammography rarely can determine the diagnosis when there is a clinically evident lesion. The test itself should really not be considered “diagnostic,” even though it is important in these settings for reasons other than determining the etiology of the palpable finding.

Although the “diagnostic” mammogram only rarely alters the management of a clinically evident abnormality, it does have some value for these patients. These are listed below.

Role of Mammographic Evaluation of the Symptomatic Woman

For the rare instance in which the mammogram can demonstrate that the palpable abnormality is benign and avoid further intervention (calcified involuting fibroadenoma, lipoma, oil cyst, galactocele, or hamartoma)

To reinforce the impression that the palpable abnormality is likely malignant and to support earlier intervention

To search the remainder of the ipsilateral breast for unsuspected cancer

To search the contralateral breast to find breast cancer that is not palpable and is clinically occult

To try to assess the extent of a malignancy and multifocality when cancer is diagnosed

Mammography Is a Screening Test Even for Symptomatic Women

The last three indications listed above for the mammogram are perhaps the most important. Most clinically evident abnormalities are benign. Just as mammography can detect early breast cancer in the asymptomatic woman, early breast cancer can be detected by mammography in the symptomatic woman. The fact is that the major role for mammography in any woman, whether she is asymptomatic or has a clinically evident problem, is screening to detect clinically unsuspected cancer.

Because there are no prospectively obtained data that prove that mammographic evaluation of a palpable abnormality has any impact on mortality, the only efficacious role for mammography is screening to detect breast cancers before they become palpable. It is scientifically inconsistent to suggest that mammography is valuable for the woman who has a lump but not to support its use for screening asymptomatic women.

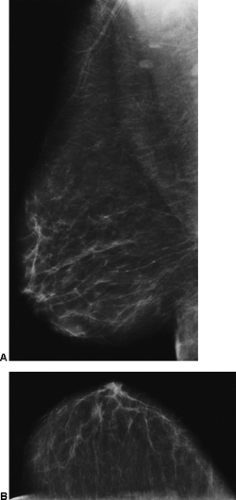

Clinical Breast Examination

Clinical breast examination (CBE) is usually a fairly crude evaluation that is compromised by marked variation in the skills of the practitioner and “inter-performer” variation. There has been a recent effort to try to standardize and improve CBE (4), but I do not suspect that this will have much influence. Most CBE is performed incompletely and badly. It is a difficult examination to do well and is often inaccurate due to the heterogeneous texture of normal

breast tissues (Fig. 21-6). It is well established, however, that there are breast cancers that can be detected by CBE that are not detected by mammography. The Health Insurance Plan of New York (HIP) demonstrated the possible value of physical examination screening to reduce the mortality from breast cancer. The women in that trial, who enjoyed a 20% to 30% decrease in mortality, had been screened by both mammography and CBE (5). It has been suggested that much of the benefit in that trial was due to the CBE because the mammography was not of particularly high quality. This may be due to the fact that the control group, in the days of the HIP, often had advanced cancers due to the lack of awareness and secrecy surrounding breast cancer, so that earlier detection by any means could reduce the rate of death. Nevertheless, there are still some small cancers that can be found only by CBE, and this may provide some advantage.

breast tissues (Fig. 21-6). It is well established, however, that there are breast cancers that can be detected by CBE that are not detected by mammography. The Health Insurance Plan of New York (HIP) demonstrated the possible value of physical examination screening to reduce the mortality from breast cancer. The women in that trial, who enjoyed a 20% to 30% decrease in mortality, had been screened by both mammography and CBE (5). It has been suggested that much of the benefit in that trial was due to the CBE because the mammography was not of particularly high quality. This may be due to the fact that the control group, in the days of the HIP, often had advanced cancers due to the lack of awareness and secrecy surrounding breast cancer, so that earlier detection by any means could reduce the rate of death. Nevertheless, there are still some small cancers that can be found only by CBE, and this may provide some advantage.

Additional support for screening using CBE was established in the Breast Cancer Detection Demonstration Project (BCDDP), where almost 9% of the cancers were

detected only by CBE and were not found by mammography (6).

detected only by CBE and were not found by mammography (6).

The benefit from clinical examination is likely to be greatest when the comparison group that is not screened has cancers diagnosed at a late stage, and even clinical examination can lead to a “downstaging” for those screened. As noted above, this is likely what happened in the HIP study. As more of the comparison-group women have their cancers detected at an earlier stage, it becomes more difficult to demonstrate added benefit from CBE. Although the efficacy of physical examination by itself to reduce mortality has not been tested, it is likely that a small number of women can benefit from periodic screening by physical examination.

Although periodic, properly performed screening with CBE, by itself, has never been shown to reduce the death rate from breast cancer in a properly performed randomized, controlled trial, it can likely detect a number of early cancers that might otherwise escape early detection. Based on anecdotal information, CBE should probably be part of a complete screening program. Unfortunately, by the time many cancers are large enough to feel, the patient’s course is often already determined and the likelihood that metastatic spread has already occurred is fairly high. Almost 50% of women with cancers that are 2 cm in size or larger have positive axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 21-7) (7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree