Gastrointestinal Radiology

Melanie P. Caserta

The authors and editors acknowledge the contribution of the Chapter 9 authors from the second edition: Tara C. Noone, MD, and Sunil Kini, MD, and the Chapter 10 authors from the third edition: David J. Ott, MD, and John R. Leyendecker, MD. The author also acknowledges Michael Chen, MD, for assistance with image preparation.

Case 12.1

HISTORY: A 56-year-old man with a long history of heartburn

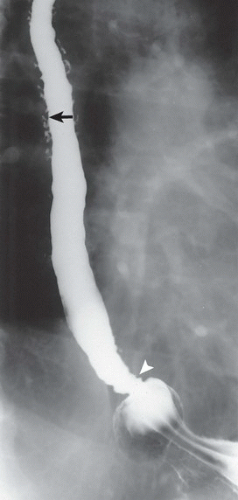

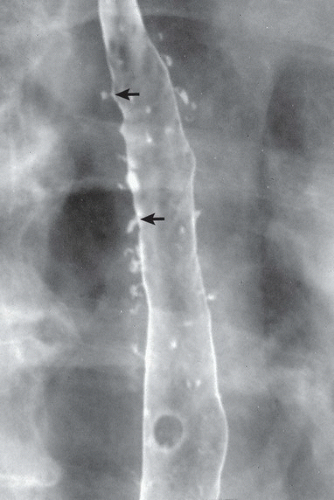

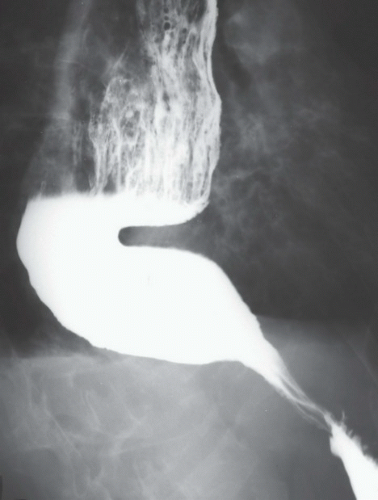

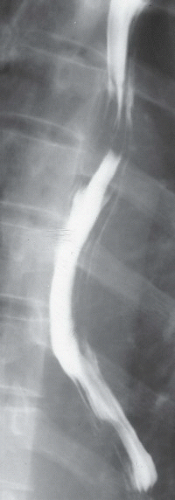

FINDINGS: Single-contrast (Fig. 12.1.1) and double-contrast (Fig. 12.1.2) esophagrams demonstrate innumerable, small, flask-shaped outpouchings projecting off the esophageal lumen (arrows). These outpouchings are several millimeters long and wide, and they have tiny ostia connecting them to the lumen of the esophagus. The distribution of the outpouchings is confined primarily to the midportion of the esophagus, although several are also seen in the distal esophagus. Demonstrated is also a sliding hiatal hernia with a stricture (Fig. 12.1.1, arrowhead) at the esophagogastric junction.

DIAGNOSIS: Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis with hiatal hernia and peptic stricture

DISCUSSION: Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis is a rare entity in which there is dilatation of the excretory ducts of submucosal mucous glands (1,2). Approximately 90% of patients have a long history of reflux esophagitis, and most have peptic strictures at the time of diagnosis. The condition is usually diagnosed by means of barium swallow, which reveals the numerous dilated excretory ducts. The distribution of pseudodiverticula may be diffuse or segmental. Although Candida albicans has been cultured from the esophagus in about one-half of affected patients, it is not thought to play any causal role in the development of pseudodiverticula and is likely just a secondary saprophyte. The condition itself is benign, and treatment should be directed toward the underlying reflux disease and stricture.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Numerous, tiny, flask-shaped outpouchings from the esophagus = intramural pseudodiverticulosis.

This entity is associated with chronic esophagitis and peptic strictures.

Case 12.2

HISTORY: Dysphagia and halitosis

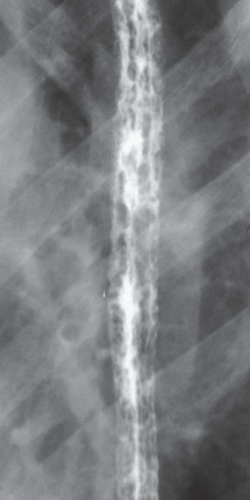

FINDINGS: Anteroposterior (Fig. 12.2.1) and lateral (Fig. 12.2.2) views of the neck obtained during a barium swallow study demonstrate a contrast-filled pouch (arrow) emanating from the posterior aspect of the esophagus just at the level of the pharyngoesophageal junction. The internal wall of the pouch is smooth, and the proximal esophageal folds are unremarkable. The proximal cervical esophagus is displaced anteriorly by the contrast-filled pouch.

DIAGNOSIS: Zenker’s diverticulum

DISCUSSION: Zenker’s diverticulum is a pulsion pseudodiverticulum at the pharyngoesophageal junction. The etiology is multifactorial but may relate to dysfunction of the upper esophageal sphincter or loss of tissue compliance in the same anatomic location (3,4). This produces elevated pressures in the hypopharynx and eventually leads to herniation of mucosa through a triangular defect in the posterior aspect of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle known as Killian’s dehiscence. These “diverticula” may become large, and patients frequently present with dysphagia, regurgitation, aspiration, pneumonia, weight loss, and halitosis.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

A Zenker’s diverticulum is a pulsion pseudodiverticulum that occurs through Killian’s dehiscence.

Case 12.3

HISTORY: Epigastric pain

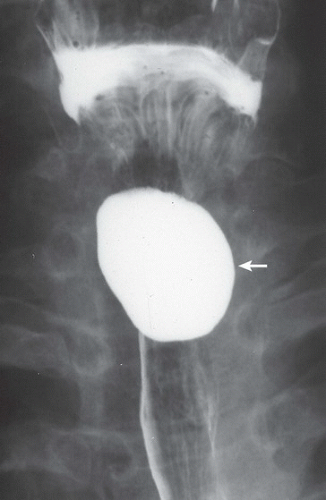

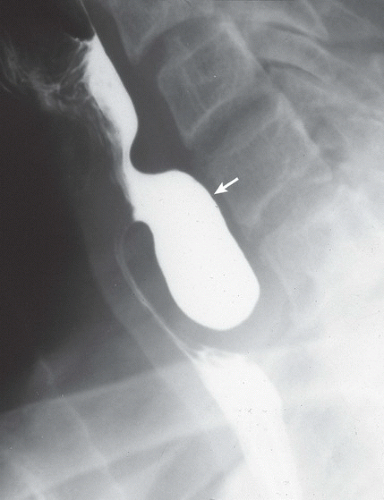

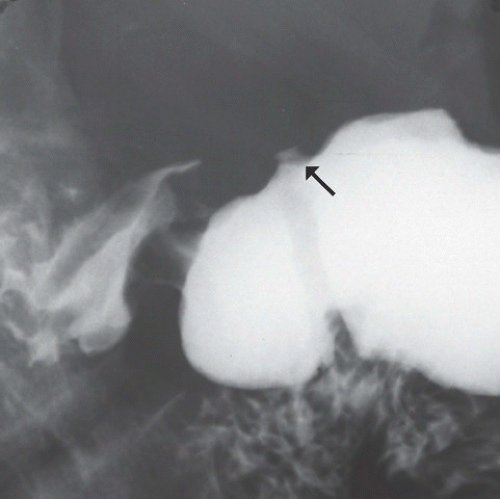

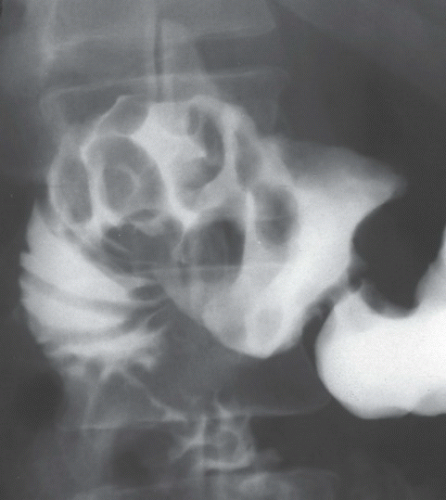

FINDINGS: Views from barium upper gastrointestinal series in two patients (Figs. 12.3.1 and 12.3.2) demonstrate small collections of contrast material along the lesser curvature of the stomach, consistent with gastric ulcers. At the base of each ulcer crater, a thin, radiolucent line (Fig. 12.3.1, arrow) and a thicker line (Fig. 12.3.2, arrow) are seen separating the ulcers from the gastric lumen (arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Benign gastric ulcers, one with a thin Hampton’s line; the other with a thicker ulcer collar

DISCUSSION: Numerous radiographic signs have been described to establish benignity of gastric ulcers (5). Smooth mucosal folds that extend to the edge of the ulcer crater are a reliable indicator of benignity. The smooth nature of the folds must be seen with certainty because nodular radiating folds may indicate an ulcerated malignancy. Other signs of a benign gastric ulcer are the ulcer collar, Hampton’s line, and the penetration sign. The ulcer collar represents a rim of mucosa along the margin of the ulcer crater that is thickened by submucosal edema. A similar sign, the Hampton’s line, is an extremely narrow, radiolucent line (1-2 mm) that separates the ulcer crater from the gastric lumen. This sign is rarely seen but virtually ensures the benign nature of the ulcer because a tumor mass is not be expected to preserve a thin band of normal mucosa at its margin. The penetration sign is seen when the ulcer crater, viewed in profile, projects beyond the gastric lumen. The single best sign of a benign ulcer is complete healing after a course of conservative medical therapy.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Signs of a benign gastric ulcer include smooth, radiating mucosal folds; penetration sign; ulcer collar; and, especially, Hampton’s line.

Complete ulcer healing with medical therapy is the most reliable sign of benignity.

Case 12.4

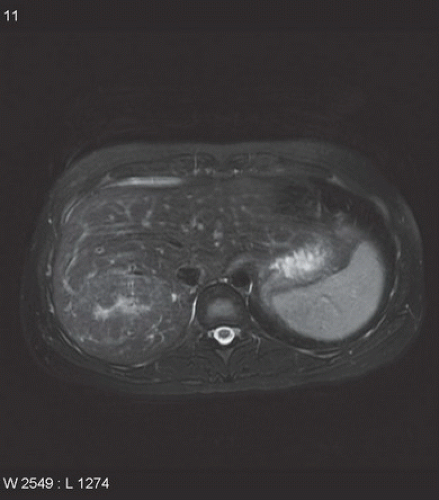

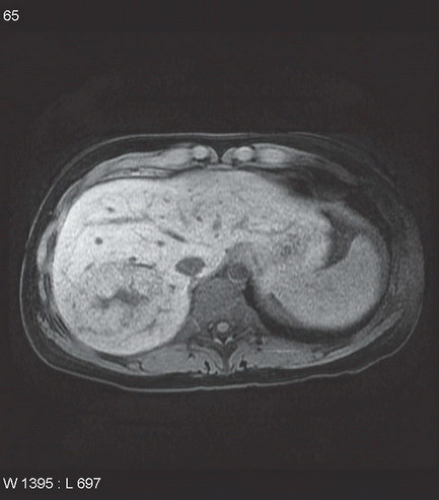

HISTORY: Liver lesion identified on prior computed tomography (CT)

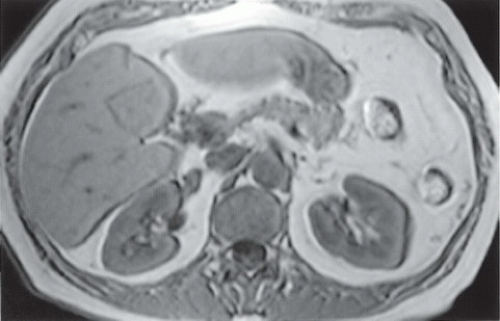

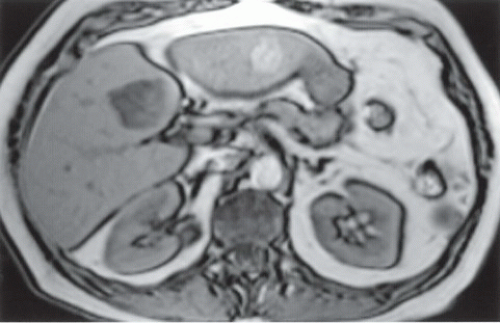

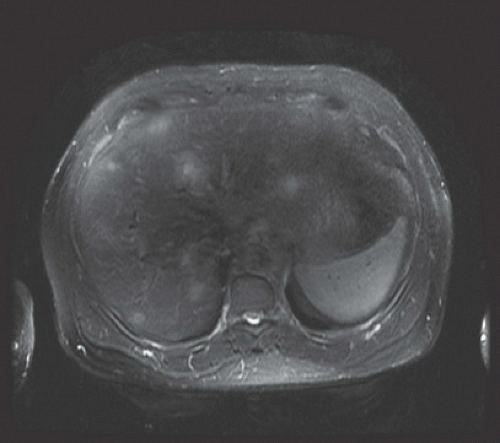

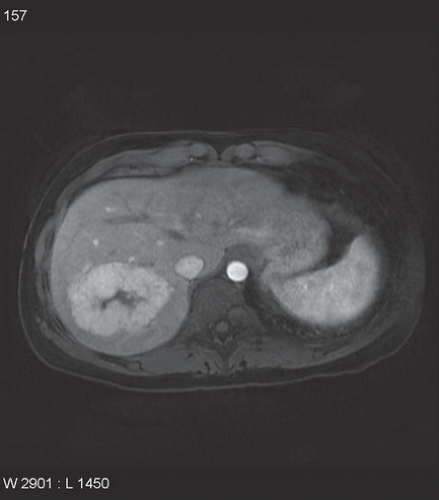

FINDINGS: Axial, in-phase spoiled-gradient-echo (SGE) (Fig. 12.4.1) and axial, out-of-phase SGE (Fig. 12.4.2) T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images. The out-of-phase image demonstrates focal signal loss within the hepatic parenchyma adjacent to the ligamentum teres.

DIAGNOSIS: Focal fatty infiltration of the liver

DISCUSSION: Fatty infiltration of the liver (i.e., hepatic steatosis) results from the accumulation of triglycerides within hepatocytes. It occurs in various disease processes, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, and ethanol abuse. When the amounts of fat and water within a given voxel are similar, the transverse magnetization of the fat and water cancel out on opposed-phase gradient echo images. This phenomenon causes areas of fatty infiltration to lose signal on opposed phase images relative to in-phase images. Common locations for focal fatty infiltration include segment IV along the porta hepatis, near the fissure for the ligamentum teres, and along the gallbladder fossa (6).

Focal fatty infiltration must be distinguished from hepatic tumors that contain intracellular lipid. Examples of tumors that can contain lipid sufficient to lose signal on opposed-phase gradient echo images include hepatic adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Focal fatty infiltration typically does not cause mass effect or displace or compress vessels (6).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Loss of signal intensity within the hepatic parenchyma between in-phase and out-of-phase images occurs in the setting of fatty infiltration.

Common locations for focal fatty infiltration include the central tip of segment IV, along the ligamentum teres, and adjacent to the gallbladder.

Focal fatty infiltration does not typically displace vessels or cause mass effect.

Case 12.5

HISTORY: Dysphagia

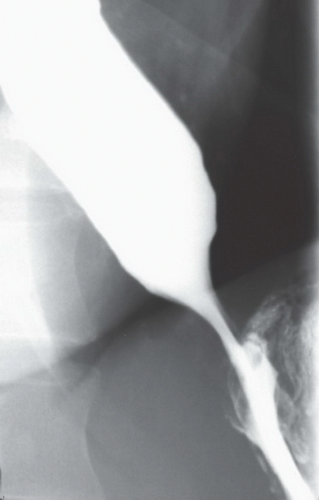

FINDINGS: An image of the lower esophagus (Fig. 12.5.1) demonstrates a smooth, tapered narrowing at the lower end; in another patient, a similar finding is seen but associated with esophageal dilatation and tortuosity (Fig. 12.5.2); both patients had esophageal aperistalsis on fluoroscopic observation.

DIAGNOSIS: Idiopathic achalasia

DISCUSSION: Idiopathic achalasia is a primary motility disorder of the esophagus of unknown etiology (7). On esophageal manometry, the two most important findings are a complete lack of esophageal peristalsis on all swallows observed and a failure of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES); the radiographic features reflect these manometric abnormalities: Esophageal peristalsis is absent, and the “beaked” appearance of the lower esophagus results from the dysfunctional LES. With more chronic and severe disease, esophageal dilatation and retention of food and secretions are observed. The most important differential diagnosis is secondary achalasia, most often owing to an invasive adenocarcinoma at the esophagogastric junction, often arising from the gastric cardia. During fluoroscopy, look for periodic relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter while drinking to distinguish primary achalasia from secondary achalasia. Secondary achalasia, also known as pseudoachalasia, will cause a fixed nonrelaxing obstruction (8).

Treatment consists of relieving the functional LES obstruction with a laparoscopic Heller myotomy or pneumatic dilatation; the use of botulinum toxin for temporary relief is another therapeutic option. Finally, patients with idiopathic achalasia are at higher risk for development of esophageal carcinoma.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Idiopathic achalasia is easily diagnosed and is a treatable esophageal motility disorder.

Gastroesophageal junctional carcinoma is the most important differential diagnosis.

Case 12.6

HISTORY: A 37-year-old, immunocompromised man with odynophagia

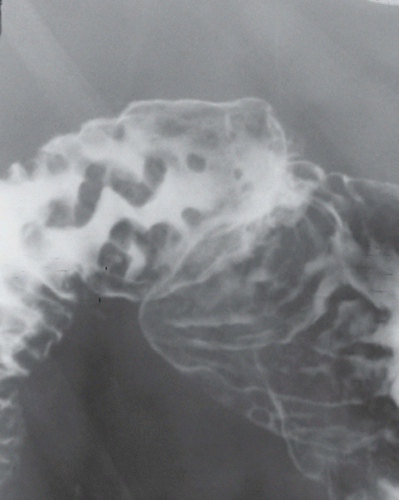

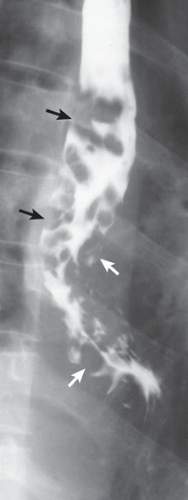

FINDINGS: Double-contrast (Fig. 12.6.1) and mucosal-relief (Fig. 12.6.2) esophagrams reveal diffuse and irregular, plaque-like filling defects.

DIAGNOSIS: Esophageal candidiasis

DISCUSSION: Infectious esophagitis is an increasingly common problem in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection, malignancy, chronic immunosuppression for organ transplantation, or other illnesses that compromise the patient’s immune status. Although various etiologic agents may be implicated in infectious esophagitis, the most common offending organism is C. albicans. Affected patients typically present with dysphagia, odynophagia, or chest pain. The radiographic appearance of candidal esophagitis is that of irregular, plaque-like filling defects that tend to be oriented along the long axis of the esophagus (9). With severe involvement, the plaques become coalescent and produce a “shaggy esophagus.” Although this appearance is characteristic of candidal esophagitis, advanced herpetic esophagitis may have a similar appearance. The compromised immune status of these patients places them at increased risk for other infections that may be superimposed on the candidal esophagitis.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Plaque-like filling defects = esophageal candidiasis.

Esophageal candidiasis is usually seen in immunocompromised patients.

Case 12.7

HISTORY: Two patients with epigastric pain

FINDINGS: A fluoroscopic spot film obtained during an upper gastrointestinal (UGI) examination (Fig. 12.7.1) shows multiple nodules within the duodenal bulb. A similar image in another patient (Fig. 12.7.2) demonstrates fold thickening and nodular erosions.

DIAGNOSIS: Duodenitis

DISCUSSION: Duodenitis is a common inflammatory process that predominately affects the duodenal bulb. The etiology is uncertain, but causative factors include excessive alcohol ingestion and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; although Helicobacter pylori has shown a near universal relationship (>90%) with duodenal ulcer, an association with duodenitis remains unproven. Radiographic detection of duodenitis is modest, and only the more severe forms are demonstrated; radiographic signs that suggest the disease include fold thickening, nodularity, and the presence of erosions; the sensitivity and specificity of these signs are inversely related with the finding of erosions being the most specific but least sensitive (10). Differential diagnosis is nearly nonexistent if multiple abnormalities are present; Brunner’s gland hyperplasia was previously the main consideration but is likely a rare disorder; indeed, before the advent of UGI endoscopy, many radiographic diagnoses of Brunner’s glands hyperplasia were likely patients with nonspecific duodenitis. Treatment initially involves cessation of potentially causative agents.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Duodenitis is a common inflammation of the duodenal bulb.

Fold thickening with nodularity and erosions are specific findings.

Case 12.8

HISTORY: UGI Bleeding

FINDINGS: The initial upright oblique full column esophagram film (Fig. 12.8.1) is unremarkable. The following film (Fig. 12.8.2), obtained with the patient in the recumbent position, demonstrates serpiginous, nodular filling defects (arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Esophageal varices

DISCUSSION: Esophageal varices represent portal-systemic venous collateral pathways. They occur most commonly in the setting of portal hypertension in which venous blood from the splanchnic system is shunted through the esophageal or paraesophageal venous plexus into the azygous system and superior vena cava. Because of the cephalad direction of flow through the varices, they are referred to as “uphill” varices. Esophageal varices develop less commonly in the setting of superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction, in which venous blood from the head, upper extremities, and trunk is shunted through the esophageal or paraesophageal venous plexus and into the portal or azygous systems. These collaterals are referred to as “downhill” varices (11). The clinical relevance of esophageal varices lies in their tendency for rupture, with potentially severe UGI bleeding.

Varices may appear as nodular, serpiginous filling defects on barium esophagography. It is important to recognize the changing character of the filling defects during fluoroscopy because fixed defects may be encountered with varicoid carcinoma. Because the varices may be intermittently decompressed as a result of esophageal peristalsis and changing perfusion pressure during the examination, various provocative maneuvers have been proposed to increase the visualization of the varices. Common maneuvers used in radiology include prone and upright patient positioning and performance of respiratory maneuvers (11,12).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Changing, serpiginous filling defects in the esophagus = varices.

Uphill varices result from portal hypertension.

Downhill varices result from SVC obstruction.

Case 12.9

HISTORY: A 30-year-old woman with a history of a malignant skin lesion

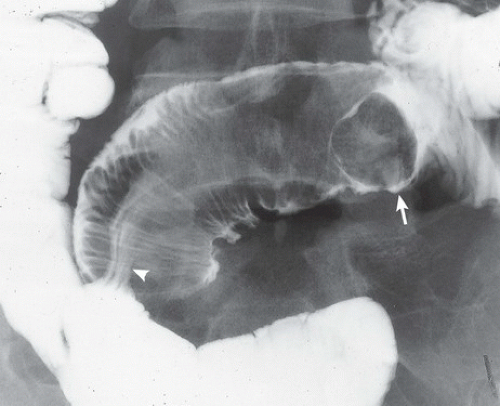

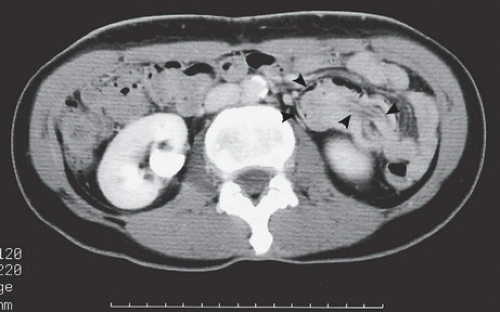

FINDINGS: A single view from a small bowel follow-through examination (Fig. 12.9.1) demonstrates a filling defect within the small bowel, surrounded by a coiled-spring pattern of mucosal folds. The leading edge of the filling defect looks like a mass (arrow). Barium extends into the central portion of the mass (arrowhead), which is a distinguishing feature of this case. CT confirms the abnormality and shows a filling defect in the small bowel, which has concentric bands of high and low attenuation (Figs. 12.9.2 and 12.9.3, arrowheads).

DIAGNOSIS: Small-bowel intussusception from metastatic melanoma

DISCUSSION: Idiopathic intussusception is a disease of the young. When intussusception is encountered in older individuals or neonates, a pathologic lead point is a primary consideration. In this case, the melanoma metastasis is seen leading the intussusceptum into the intussuscipiens. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, lymphoma, lipomas, or Meckel’s diverticula may also present as lead masses. Causes of transient intussusception include scleroderma, sprue, and cystic fibrosis. The coiled-spring appearance is caused by a projection of inflamed and engorged mucosa into a barium pool that has retrograde filled the lumen of the intussuscipiens (13,14). The alternating bands of high and low attenuation demonstrated by CT result from intussuscepted mesenteric fat contrasted with mucosal-muscular interfaces (13).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Coiled-spring appearance on small-bowel follow-through = intussusception.

Suspect a lead point in neonates, older children, and adults.

Case 12.10

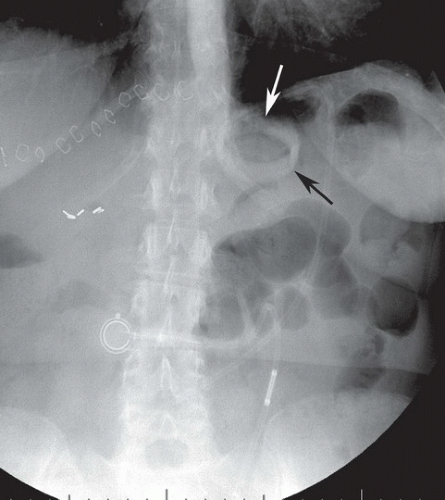

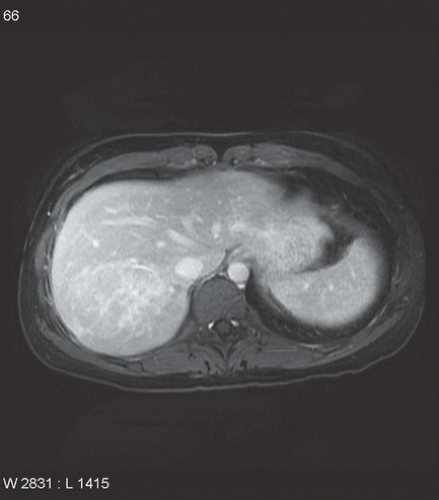

HISTORY: Follow-up after colectomy for colon cancer

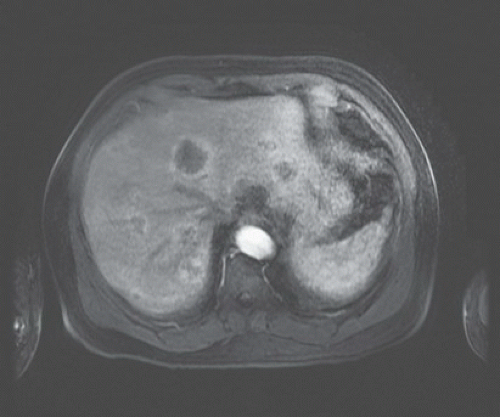

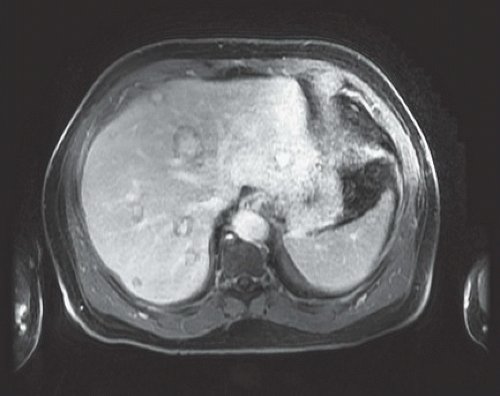

FINDINGS: Axial T2-weighted MR image (Fig. 12.10.1) through the liver shows multiple hepatic lesions that demonstrate mildly increased signal intensity relative to the liver. An arterial-phase T1-weighted MR image (Fig. 12.10.2) performed after administration of gadolinium-based contrast medium shows the lesions to initially enhance peripherally. An equilibrium-phase T1-weighted MR image (Fig. 12.10.3) shows that the lesions have enhanced centrally, whereas the lesion peripheries have relatively lower-signal intensity.

DIAGNOSIS: Liver metastases from carcinoma

DISCUSSION: Metastatic disease represents the most common type of malignant hepatic neoplasm. On MRI, liver metastases can have a highly variable appearance. However, the combination of multiple liver lesions demonstrating increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images, early peripheral enhancement, and central enhancement with peripheral low-signal intensity on delayed (equilibrium-phase) images is highly specific for metastatic carcinoma. The term peripheral washout sign has been coined to describe this particular enhancement pattern (15). Other types of malignant tumor (particularly cholangiocarcinoma) can

produce a similar enhancement pattern, so the combination of clinical history and presence of multiple lesions is helpful in suggesting the diagnosis of metastases.

produce a similar enhancement pattern, so the combination of clinical history and presence of multiple lesions is helpful in suggesting the diagnosis of metastases.

Hepatobiliary contrast agents, such as gadoxetic acid, allow for both dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging of lesions and increased lesion conspicuity on delayed T1-weighted images, which is a helpful feature in identifying metastases. Metastases are nonhepatocellular and thus will not retain the contrast on delayed imaging. Metastases appear hypointense compared with enhancing normal liver on hepatobiliary phase images (16).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Multiple liver lesions demonstrating increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images, early peripheral enhancement, and prolonged central enhancement with lower-signal intensity periphery on delayed images suggests the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma.

Case 12.11

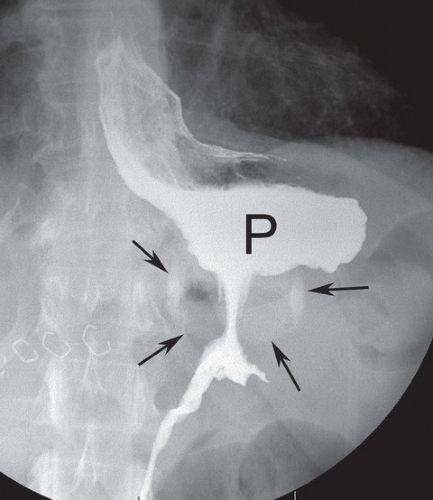

HISTORY: Patient who underwent laparoscopic adjustable band placement 3 years ago, now presents with abdominal pain after eating

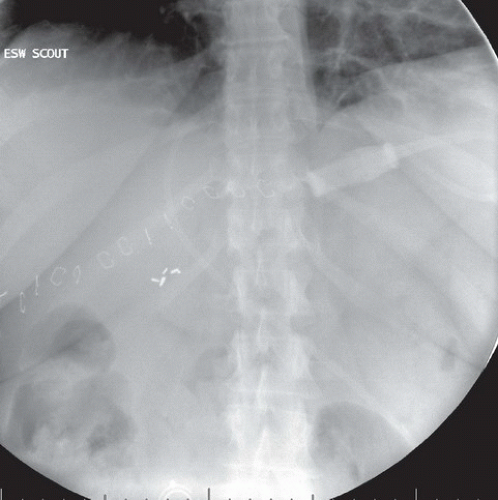

FINDINGS: The scout film (Fig. 12.11.1) and image from a contrast UGI examination (Fig. 12.11.2) were obtained one day after surgery. Note the appearance and position of the gastric band below the esophagogastric junction in the left upper quadrant (Fig. 12.11.1). The band appears disk-like, with the left lateral aspect directed toward the left shoulder. On the contrast UGI (Fig. 12.11.2), a small gastric pouch is seen above the band. Both images demonstrate the expected postoperative findings of the gastric band. Similar images, obtained 3 years later at the time of the patient’s current presentation (Figs. 12.11.3 and 12.11.4) show alteration of the band position (arrows) and a larger gastric pouch (P) above the band. On the scout film (Fig. 12.11.3) the position of the band now has the configuration of the capital letter “O” (arrows), the so-called O sign. After the administration of oral contrast, the pouch is larger than expected (P), confirming downward slippage of the band.

DIAGNOSIS: Slipped gastric band exhibiting the O sign.

DISCUSSION: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) bypass is increasing in popularity as a treatment for obesity and has several advantages over other bariatric surgeries, including adjustability, reversibility, lack of anatomic alteration of the GI tract, and low surgical risk to the patient. In the immediate postoperative period, a limited UGI contrast study is often performed to evaluate for position of the band and any early complications such as obstruction or leak. The pouch size, band position and orientation, patency, size of gastric lumen within the band (normally 3-4 mm), and emptying into the remainder of the stomach are evaluated. The tubing and port are also assessed for intact connections and port position.

In addition to qualitative visual assessment with imaging, band position can be quantitatively evaluated with measurement of the “phi angle.” The phi angle is constructed using the vertical axis of the spine and the long axis of the band, and it should range between 4° and 58°. The gastric pouch should be small, approximately 4 cm in diameter, when adequately filled (17). Contrast material should readily pass into the stomach, and it may be normal to see some delay in pouch emptying above the band. Periodically, the LAGB may need adjustments with initial adjustment typically performed 4 weeks after solids are introduced into the diet.

Complications related to LAGB can occur in the early postoperative period or later and can be considered in three categories: band-related, port-related (rare), and other. Band-related complications occur more commonly and include slippage, misplacement, stomal stenosis, pouch dilatation, and band erosion. Band slippage is a relatively common complication, which may result in stomal stenosis or obstruction necessitating acute surgical intervention. Slippage is defined as upward herniation of the distal stomach through the band, resulting in pouch enlargement (17). On scout imaging prior to UGI examination, a slipped band may assume an O-shaped configuration, the so-called O sign, which occurs when the weight of the herniated stomach causes the band to tilt along its horizontal axis (18). The band can then be seen partly en face and the phi angle will be increased.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Normal position of the lap band is pointing toward the left shoulder with a phi angle between 4° and 58°.

A slipped gastric band may assume an “O” shape (the “O” sign).

Slippage of the gastric band can cause serious complications and may require acute surgical intervention.

Case 12.12

HISTORY: Incidental finding on CT scan of the abdomen and MRI of the liver performed prior to and after intravenous administration of gadobenate dimeglumine