Genitourinary Radiology

Brian Dupree

Samuel Porter

Judson R. Gash

The authors and editors acknowledge the contribution of the Chapter 11 author from the third edition: Daniel J. Kirzeder, MD and Chapter 10 authors from the second edition: Tara C. Noone, MD, Norbert Burzynski, MD, Robert Bechtold, MD, and Raymond B. Dyer, MD.

Case 13.1

HISTORY: Patient with history of urinary tract infections.

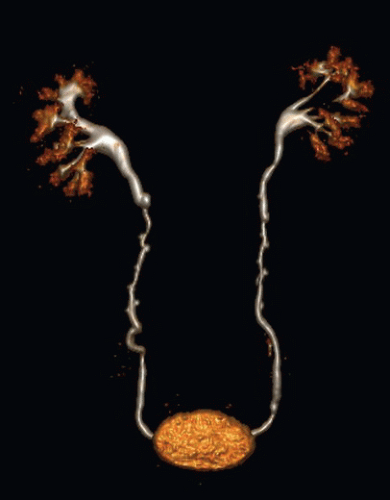

FINDINGS: Coronal volume rendered 3D image (Fig. 13.1.1) of the urinary tract during the excretory phase demonstrates multiple small ureteral outpouchings

DIAGNOSIS: Ureteral pseudodiverticulosis

DISCUSSION: Ureteral pseudodiverticula are small outpouchings of the ureteral lumen that are sharply demarcated and usually vary in size from 1 to 3 mm in width and length (1,2). Three to eight diverticula clustered over a distance of 2 to 6 cm in the midureter are commonly seen. The involved ureteral segment is often narrowed but is not usually obstructed. Bilateral ureteral involvement may be seen in up to 50% of cases. The outpouchings represent down-growth of the transitional epithelium into the ureteral wall, probably as a result of epithelial hyperplasia. Because the outpouchings do not contain all layers of the ureteral wall, they are pseudodiverticula (1,2). The hyperplastic response has been associated with urinary stone disease and obstruction, infection, and transitional cell carcinoma. Patients with pseudodiverticula therefore should be monitored closely for the development of transitional cell neoplasms, especially in the bladder (3).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Small outpouchings of the ureter that do not contain all the layers of the ureteral wall = pseudodiverticula.

Patients with pseudodiverticulosis should be monitored for the development of transitional cell carcinoma.

Case 13.2

HISTORY: A 32-year-old female undergoing infertility workup

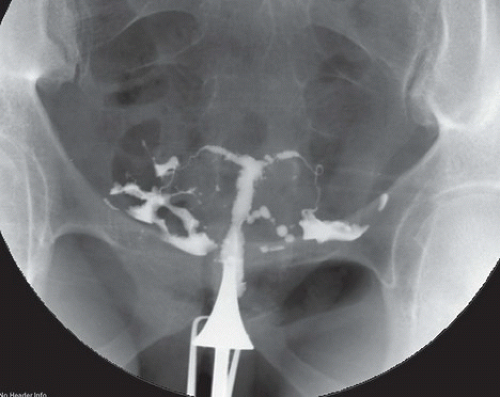

FINDINGS: Hysterosalpingogram (Fig. 13.2.1) shows a narrowed endocervical canal and a hypoplastic, small uterine cavity with a T-shaped configuration. Multiple irregularities consistent with fibrous scars (synechiae) are present.

DIAGNOSIS: Uterine hypoplasia secondary to in utero DES exposure

DISCUSSION: Diethylstilbestrol (DES) is a potent synthetic estrogen that was prescribed between the late 1940s until about 1970 for pregnant women to prevent recurrent spontaneous abortions, premature deliveries, and other pregnancy complications. The strong estrogen effects of DES disrupt the differentiation of estrogen-sensitive organs during organogenesis and can lead to structural fetal malformations of the uterus and fallopian tubes. Abnormalities of the uterine cavity are detected by hysterosalpingogram (HSG) in as many as 69% of DES-exposed women (4) and most commonly include uterine hypoplasia (a T-shaped uterine cavity), bands and synechiae, and irregular uterine margins (5). MR imaging has also been shown to adequately depict uterine abnormalities associated with DES exposure (6). The intrauterine abnormalities associated with DES exposure predispose women to menstrual dysfunction and pregnancy complications such as spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancy, and prematurity (7,8). In addition, clear cell carcinoma of the vagina is seen in 0.1% of patients with a history of DES exposure (9).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Uterine hypoplasia with a T-shaped uterine cavity configuration is the classic imaging manifestation of previous in utero DES exposure.

The intrauterine abnormalities associated with DES exposure predispose women to pregnancy complications including spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancy, and prematurity.

Case 13.3

HISTORY: A 72-year-old female with complaints of pneumaturia, fecaluria, and recurrent urinary tract infections

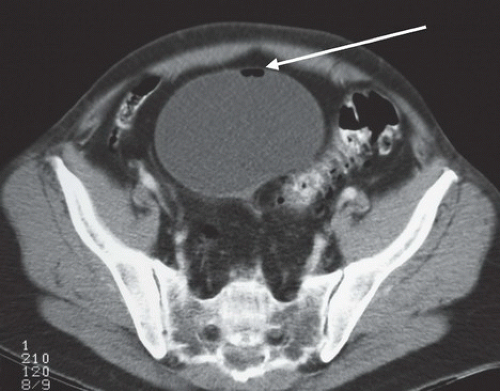

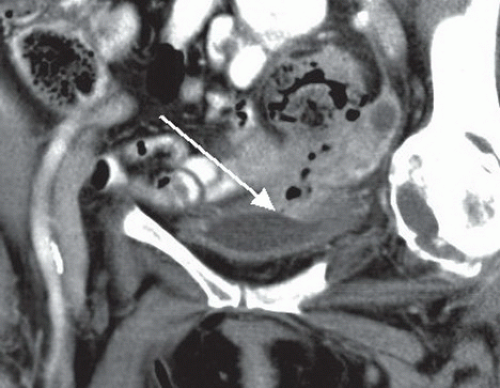

FINDINGS: Contrast-enhanced CT in the axial plane (Fig. 13.3.1) demonstrates air within the bladder lumen (arrow) and a reformatted coronal image (Fig. 13.3.2) demonstrates a direct communication from a sigmoid diverticulum to the bladder (arrow).

DIAGNOSIS: Colovesical fistula

DISCUSSION: A colovesical fistula is an abnormal internal connection between the colon and urinary bladder. The most common cause of colovesical fistula is sigmoid diverticulitis (10). Other etiologies include colorectal adenocarcinoma, inflammatory bowel disease, radiation therapy, pelvic surgery, and foreign bodies (11). Patients commonly present with nonspecific irritative symptoms of cystitis and have a positive urine culture. The classic symptoms of pneumaturia and fecaluria usually occur late in the disease process (12). In the CT evaluation of patients with suspected colovesical fistula, a scan should be performed with an enteric contrast agent but before the administration of intravenous contrast. The presence of enteric contrast within the bladder is diagnostic of a fistula. Additional CT findings of colovesical fistula include gas within the bladder lumen (in the absence of recent bladder catheterization) and thickened bladder or bowel wall adjacent to the fistula (11). In addition to documenting the fistula, CT also allows the evaluation of intraluminal and extraluminal pathologic conditions that may be helpful in planning surgical intervention (12). Cystoscopy and colonoscopy are useful in the evaluation of patients with colovesical fistula, particularly to exclude underlying neoplasm.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

The most common cause of colovesical fistula is sigmoid diverticulitis; however, underlying neoplasm must be excluded.

CT finding of colovesical fistula include gas within the urinary bladder lumen, thickening of the bladder or colon wall adjacent to the fistula, and a fistula tract opacified with air or enteric contrast.

Reformatted coronal imaging is often very valuable for demonstrating the fistula.

Case 13.4

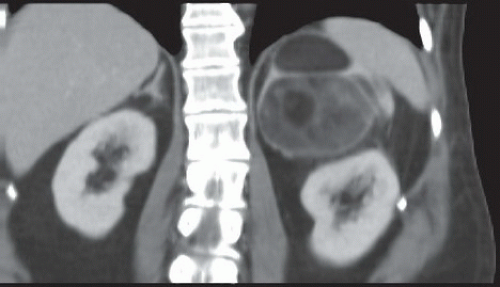

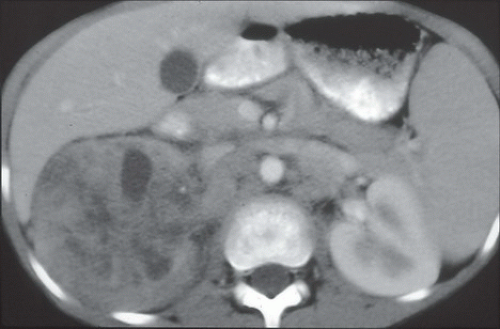

HISTORY: A 25-year-old male with history of seizures who presents with left flank pain

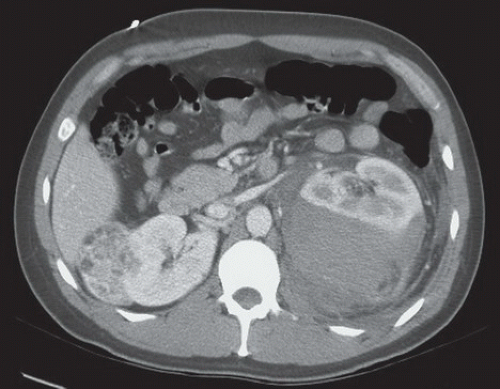

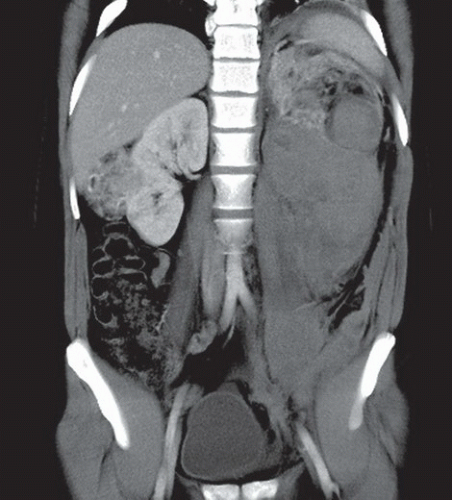

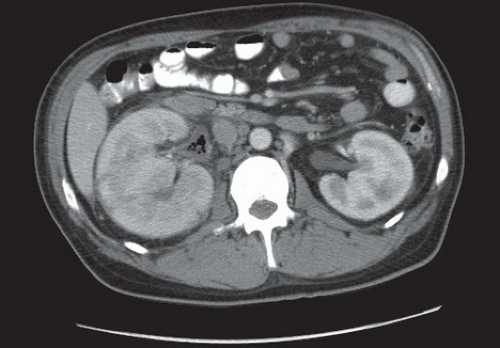

FINDINGS: Contrast-enhanced axial CT (Fig. 13.4.1) shows a large perinephric hematoma, which anteriorly displaces and deforms the left kidney. Coronal MPR image from the same CT scan (Fig. 13.4.2) shows, in addition to the large perinephric hemorrhage, bilateral fat-containing renal lesions.

DIAGNOSIS: Bilateral angiomyolipomas (AMLs) with left perinephric hematoma secondary to spontaneous left AML hemorrhage

DISCUSSION: Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), or Bourneville disease, is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder that is characterized by hamaratomatous tumors involving multiple organ systems. Hamaratomatous tumors comprise adipose tissue, thick-walled blood vessels, and sheets of smooth muscle in variable proportion. AMLs are renal hamaratomatous tumors present in up to 80% of patients with TSC. Of the three renal manifestations of TSC (AMLs, cysts, and rarely, renal cell carcinoma), AMLs are by far the most common, and they are often multiple and bilateral (13). Radiographically, AMLs present as fat-containing renal lesions, often diagnosed on CT or MRI. The larger the AML, the more likely to hemorrhage, and thus lesion >4 to 5 cm tend to be treated (excised or embolized), whereas smaller lesions are typically followed.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Multiple bilateral renal angiomyolipomas are the most common renal manifestation of TSC.

Larger AMLs (>4 cm) are commonly treated secondary to threat of spontaneous hemorrhage.

Case 13.5

HISTORY: A 5-day-old female infant with a history of prenatal cyst and a lower abdominal mass

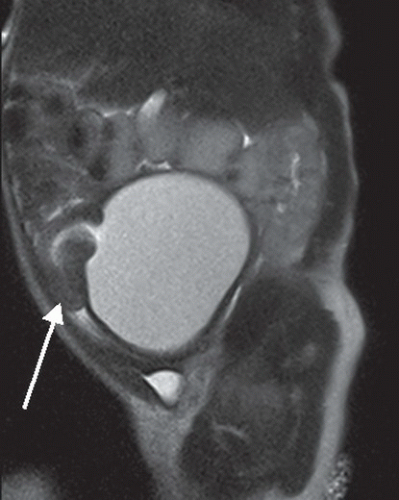

FINDINGS: Sagittal T2-weighted image of the pelvis (Fig. 13.5.1) demonstrates a severely dilated fluid-filled vagina that displaces the uterus (arrow) anteriorly and superiorly.

DIAGNOSIS: Hydrocolpos

DISCUSSION: The most common pelvic masses in neonates include hydrocolpos, hydrometrocolpos, and ovarian cysts. Hydrocolpos is defined as distension of the vagina. Both hydrocolpos and hydrometrocolpos can result from vaginal or cervical stenosis, hypoplasia, or agenesis (Meyer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Houser syndrome), which is often associated with additional congenital anomalies (14). Hydrocolpos in patients with a persistent urogenital sinus must be diagnosed and treated early in life to avoid potential complications. Some cases of hydrocolpos are identified on prenatal ultrasound. MRI has become an alternative and complementary method for the equivocal prenatal cases. It provides excellent anatomic detail and soft-tissue contrast with multiple reconstruction planes and a large field of view. Shorter MRI acquisition times reduce the effects of fetal motion and have expanded the role MRI in these settings (15). Transabdominal indwelling vaginostomy tube is the preferred approach for some pediatric surgeons. The most common complication is compression of the trigone, causing extrinsic ureterovesical obstruction, leading to megaureters and hydronephrosis, which can ultimately cause renal failure. Surgically draining the hydrocolpos may significantly improve the hydronephrosis (16).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Hydrocolpos is a distended vagina filled with fluid that may present as a cystic mass on prenatal ultrasound or as a palpable mass on postnatal physical exam.

MRI has become a complementary modality for the equivocal prenatal ultrasound.

The most common associated complication is hydronephrosis secondary to extrinsic obstruction of the ureterovesical junction.

Case 13.6

HISTORY: A 62-year-old female with complaint of “bladder spasms”

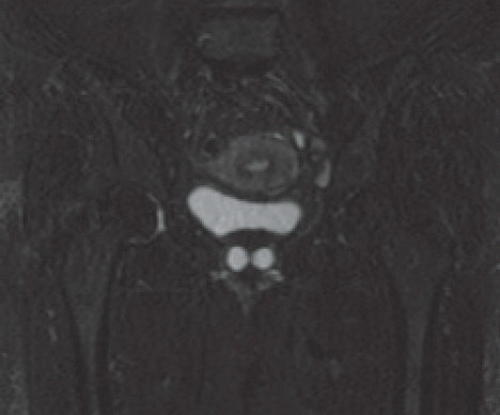

FINDINGS: Axial CT (Fig. 13.6.1) and coronal T2-weighted MR (Fig. 13.6.2) images through the pelvis in the same patient demonstrate a cystic collection “surrounding” the urethra.

DIAGNOSIS: Urethral diverticulum

DISCUSSION: Urethral diverticula are estimated to occur in 1% to 6% of women, most often between the third and sixth decades of life. Multiple nonspecific genitourinary symptoms predominate including repeated lower urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, dysuria, frequency and urgency, urethral pain, dyspareunia, hematuria, and postvoid dribbling (17). The majority of urethral diverticula are located in the middle third of the urethra and often involve the posterolateral wall. Most urethral diverticula are the sequelae of periurethral gland infection that result in glandular dilatation and then progress to fistulization with the urethra (18). It should be noted that most urethral diverticula appear to “surround” the urethra, unlike most diverticula, that appear as outpoutchings. Complications of urethral diverticulum include recurrent infection, urinary incontinence, calculus formation, and development of intradiverticular neoplasms. Urethral diverticula are associated with increased incidence—owing to urinary stasis—of stone formation and malignancy, especially urothelial carcinoma. Various diagnostic methods have been used to evaluate the female urethra including voiding cystourethrography, double-balloon urethrography, Ultrasound (US), CT, CT voiding urethrography and virtual urethroscopy, MR imaging, and fiberoptic urethroscopy. MRI has become the imaging study of choice with its multiplanar capabilities and excellent soft-tissue contrast (19). Transvaginal diverticulectomy is the most common surgical treatment.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

A urethral diverticulum appears as cystic lesion adjacent to or surrounding the midurethra.

A filling defect in a urethral diverticulum may represent calculus formation or intradiverticular neoplasm. Adenocarcinoma is the most common diverticular malignancy.

Case 13.7

HISTORY: A 47-year-old man with history of adrenal mass

FINDINGS: An unenhanced, axial CT image of the abdomen (Fig. 13.7.1) shows a large, left adrenal mass with obvious low-attenuation fatty elements and several internal septations. Coned coronal reformatted CT image (Fig. 13.7.2) shows the mass displaces the left kidney inferiorly. A well-defined fat plane separates the mass form the left kidney, confirming that the mass arises from an extrarenal location.

DIAGNOSIS: Adrenal myelolipoma

DISCUSSION: Adrenal myelolipomas are benign tumors comprising variable amounts of mature adipose cells and hematopoietic tissue. This neoplasm is functionally inactive and is usually discovered incidentally during abdominal imaging or autopsy (20,21). Although most myelolipomas are asymptomatic, hemorrhage or necrosis can occur within the tumor, and adjacent structures may be compressed, especially by larger lesions. The demonstration of well-defined macroscopic fat within an adrenal mass on CT examination virtually confirms the diagnosis of adrenal myelolipoma. Other considerations in the differential diagnosis of a suprarenal fatty mass include an exophytic renal or extrarenal angiomyolipoma, a retroperitoneal teratoma, lipoma, or possibly a liposarcoma. Careful analysis of the lesion for exact location, margination, internal consistency, and CT attenuation values should allow a correct diagnosis. Tumors with irregular margins, internal heterogeneity, significant contrast enhancement, and attenuation values greater than that of normal fat should be considered suggestive of malignancy (21,22). Resection is recommended for symptomatic lesions, those that grow during surveillance intervals, or those that are >7 cm (because of increased risk of bleeding and rupture).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Myelolipomas are benign, nonfunctioning tumors containing fat and marrow elements.

Precontrast CT scans or MR images are most useful to identify fat within adrenal lesions.

Case 13.8

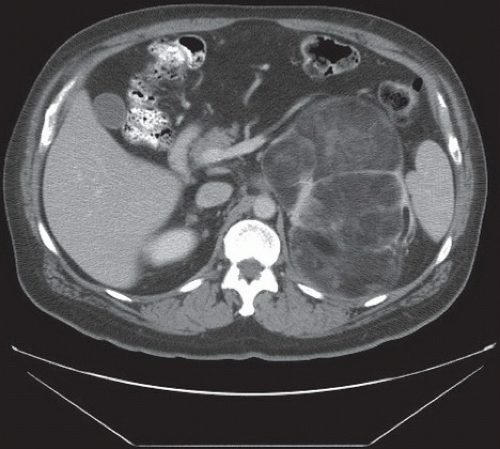

HISTORY: A 17-year-old female 8 days after severe trauma. CT without contrast in a different patient several months after trauma

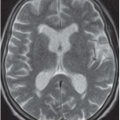

FINDINGS: Axial contrast-enhanced CT image (Fig. 13.8.1) shows lack of peripheral cortical contrast enhancement bilaterally, with normal enhancement of the renal medulla. A thin rim of enhancement of the very periphery of kidneys is seen bilaterally (arrows). A follow-up CT image (different patient) showing a thin rim of renal cortical calcification consistent with cortical nephrocalcinosis (Fig. 13.8.2).

DIAGNOSIS: Acute renal cortical necrosis

DISCUSSION: Acute renal cortical necrosis, results from ischemia of the renal cortex secondary to decreased arterial perfusion. On a contrast-enhanced CT immediately following the insult, acute cortical necrosis manifests as lack of enhancement of the peripheral renal cortex, with normal medullary enhancement (23). A thin rim of enhancing cortical tissue is classically visualized at the extreme periphery secondary to preservation of the renal capsular blood flow. With time (approximately 2 months later), the kidney will atrophy and cortical nephrocalcinosis may occur (24). Although the exact pathologic mechanism of acute cortical necrosis is not precisely known, intrarenal vascular spasm or intravascular thrombosis leading to cortical ischemia are possible explanations. Cortical necrosis may develop as a consequence of shock (trauma, etc.), obstetric complications (i.e., abruptio placentae, placenta previa, septic abortion, eclampsia), transfusion reaction, or other causes of hemolysis, endotoxins, and renal allograft rejection (25).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Renal cortical necrosis manifests acutely as decreased enhancement of the renal cortices on contrast-enhanced CT.

Acute renal cortical necrosis is most commonly seen in the setting of hemorrhagic shock, in particular in the setting of obstetric complication.

Cortical nephrocalcinosis is a common sequela of acute renal cortical necrosis.

Case 13.9

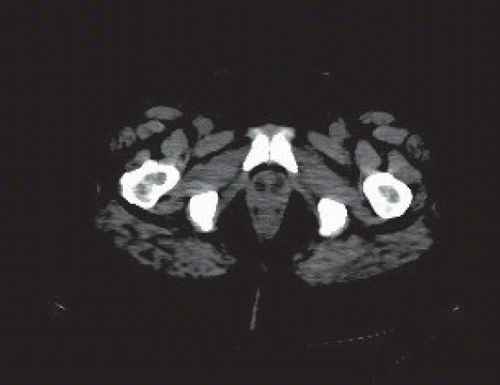

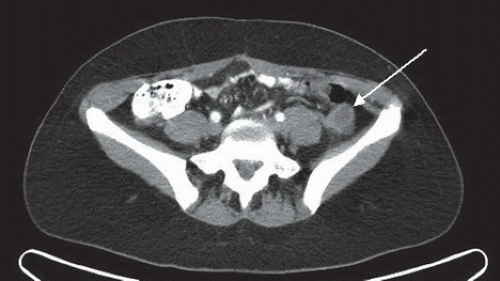

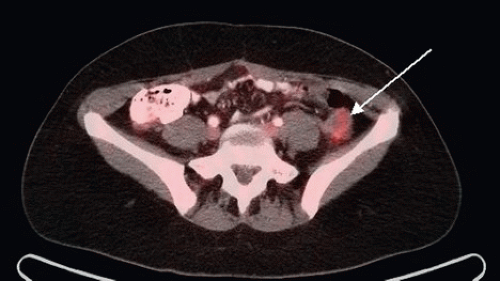

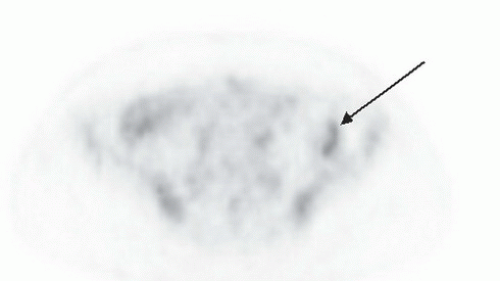

HISTORY: A 38-year-old female with a history of cervical carcinoma referred for a surveillance imaging PET/CT

FINDINGS: Axial CT, PET, and fused images from a PET/CT (Figs. 13.9.113.9.2 to 13.9.3) demonstrate a 3-cm rounded cystic and solid mass (arrows) in the low left paracolic gutter with moderate FDG activity (SUV = 3.8)

DIAGNOSIS: Transposed ovary

DISCUSSION: Therapeutic irradiation of the pelvis for malignancy ruins the ovary, resulting in ovarian failure with menopausal symptoms. Thus in patients with midline malignancies such as cervical carcinoma requiring radiation treatment, who wish to preserve function and potential fertility options, the ovaries can be surgically transposed out of the anticipated radiation field. The procedure comprises severing the uterine and broad ligament attachments, and moving the ovary, along with its suspensory ligament and gonadal vascular pedicle, outward into the low paracolic gutter, just lateral to the cecum or descending colon (26). One or both ovaries may be transposed. This is all well and good until the uninitiated radiologist misdiagnoses the transposed ovary as a peritoneal metastatic deposit (27). This is particularly possible as the normal premenopausal ovary can demonstrate (even after hysterectomy) moderate hypermetabolic activity. Obviously being acquainted with this procedure is necessary to avoid this important pitfall. Surgical history can clinch the diagnosis, but as radiologists, to rely on having that, as we know, is even a bigger pitfall. Fortunately, there are imaging clues that can help us distinguish a transposed ovary from a metastasis. The morphology of the normal ovary is helpful. Usually the premenopausal ovary, comprising small cysts within a solid background, is recognizable, particularly on

MRI. However, the ovary may be devoid of cysts and look solid, or be full of cysts and look cystic. A second clue, often used to identify the ovary on CT in general, is following the gonadal veins from their superior origin (IVC on the right, renal vein on the left) down to the area in question. The gonadal veins, when the ovaries are transposed, deviate laterally over the psoas muscles, coursing laterally behind the colon directly to the ovary, and can be followed in most cases of transposition. Finally, a thoughtful surgeon will often place a surgical clip or two in the area of a transposed ovary allowing its identification (not so much for the diagnostic radiologist, but for the radiation oncologist) (28).

MRI. However, the ovary may be devoid of cysts and look solid, or be full of cysts and look cystic. A second clue, often used to identify the ovary on CT in general, is following the gonadal veins from their superior origin (IVC on the right, renal vein on the left) down to the area in question. The gonadal veins, when the ovaries are transposed, deviate laterally over the psoas muscles, coursing laterally behind the colon directly to the ovary, and can be followed in most cases of transposition. Finally, a thoughtful surgeon will often place a surgical clip or two in the area of a transposed ovary allowing its identification (not so much for the diagnostic radiologist, but for the radiation oncologist) (28).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Radiation therapy for pelvic malignancies results in ovarian failure, and to avoid this, the ovaries can be surgically transposed out of their normal location (and out of the radiation field).

The transposed ovary can mimic a peritoneal metastatic deposit.

Knowledge of typical ovarian appearance, following the gonadal vessels, and a surgical clip (along with history, of course) can be used to differentiate a normal transposed ovary from a metastasis.

Case 13.10

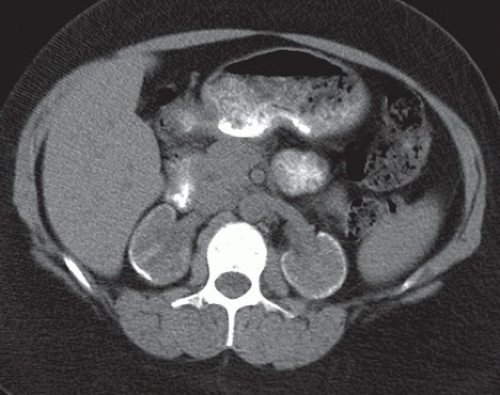

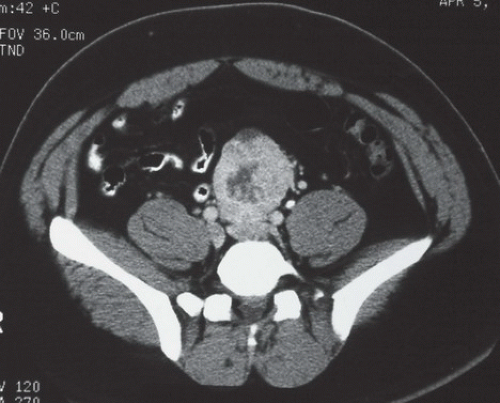

HISTORY: A 19-year-old male with history of hypertension

FINDINGS: Axial contrast-enhanced CT image of the lower abdomen (Fig. 13.10.1) shows a hypervascular mass arising just anterior to the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels. The mass demonstrates heterogeneous peripheral enhancement and a central hypodense region suggesting internal necrosis.

DIAGNOSIS: Pheochromocytoma at the organ of Zuckerkandl

DISCUSSION: Paragangliomas are tumors arising from chromaffin cells of the autonomic nervous system (29). Paragangliomas arising from the adrenal medulla are termed pheochromocytomas and the term paraganglioma is commonly used to refer to extra-adrenal tumors. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas often result in elevated serum catecholamine levels and the related clinical symptoms of hypertension, palpitations, tachycardia, diaphoresis, or headache. Pheochromocytomas are classically described according to the rule of 10s: 10% extra-adrenal, 10% malignant, 10% bilateral, 10% familial, and 10% are not associated with hypertension. However, recent studies suggest that as many as 25% of pheochromocytomas are extra-adrenal in location (30), originating within the sympathetic neural tissue outside the adrenal gland. One of the most common abdominal locations for extra-adrenal paragangliomas is the organ of Zuckerkandl, followed by the bladder and the sympathetic trunk (30). The organ of Zuckerkandl is the term given to the confluence of para-aortic sympathetic tissue just below the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery. Paragangliomas are usually heterogeneous in appearance on CT and intensely enhance after contrast administration. The typical hyperintense appearance on T2-weighted MR imaging sequences has been described as “light bulb” bright, although this is seen less commonly than a heterogeneous necrotic mass. Once diagnosed, treatment for paragangliomas arising from the organ of Zuckerkandl is surgical excision (31).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Extra-adrenal paragangliomas commonly arise from the organ of Zuckerkandl, at the aortic bifurcation.

Case 13.11

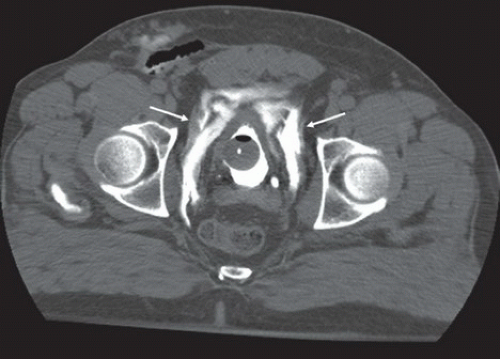

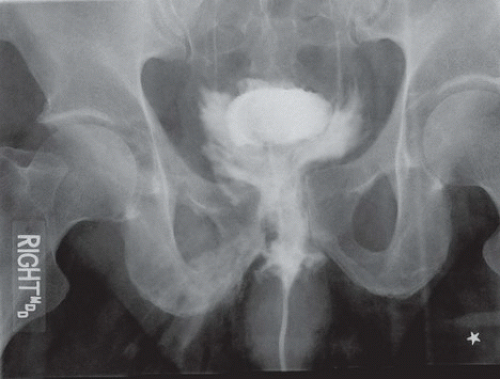

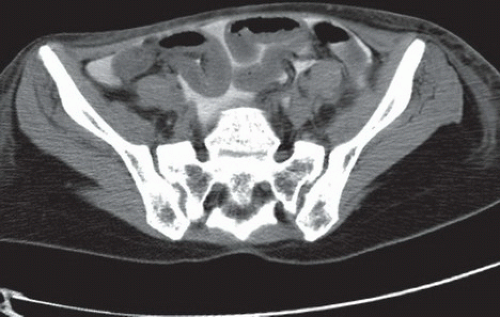

HISTORY: Two patients involved in motor vehicle accidents with blunt pelvic trauma

FINDINGS: Imaging evaluation of the first patient included CT cystogram image of the pelvis at the level of the acetabular roof (Fig. 13.11.1) and a pelvic radiograph. The axial CT image demonstrates rupture of the bladder wall with accumulation of contrast in the molar tooth-shaped prevesical extraperitoneal space (arrows). The anteroposterior pelvic radiograph (Fig. 13.11.2) demonstrates ill-defined flame-shaped contrast accumulation along both sides of the bladder; however no bowel is outlined by contrast. Frontal pelvic radiograph of the second patient performed after catheterization of the bladder and instillation of contrast material (Fig. 13.11.3) shows contrast material outlining loops of bowel in the peritoneal space. Follow-up axial CT image (Fig. 13.11.4) confirms intraperitoneal location of contrast material.

DIAGNOSIS: Extraperitoneal bladder rupture (patient 1) and intraperitoneal bladder rupture (patient 2)

DISCUSSION: The possibility of bladder injury should be considered in all patients who suffer

blunt or penetrating pelvic trauma. Gross hematuria occurs in up to 95% of cases of bladder rupture. Extraperitoneal bladder rupture (62% of major bladder injuries) is usually associated with pelvic fractures and is classified into simple and complex subtypes. In simple extraperitoneal rupture, contrast extravasation is limited to the pelvic extraperitoneal space. In complex extraperitoneal rupture, contrast extravasation extends beyond the prevesical space into the thigh, scrotum, or perineum, implying a fascial boundary injury (32,33). Treatment is usually nonsurgical catheter drainage. This approach is unlike intraperitoneal bladder rupture, which requires surgical management. With intraperitoneal rupture (25% of major bladder injuries), the irritative effect of urine exposed to the large surface area of the peritoneum can cause rapid development of chemical peritonitis, which complicates the patient’s clinical management. Intraperitoneal bladder rupture is generally considered a surgical emergency necessitating urgent primary repair of the bladder wall (32,33). Occasionally, combined bladder ruptures occur with both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal components (12% of bladder injuries).

blunt or penetrating pelvic trauma. Gross hematuria occurs in up to 95% of cases of bladder rupture. Extraperitoneal bladder rupture (62% of major bladder injuries) is usually associated with pelvic fractures and is classified into simple and complex subtypes. In simple extraperitoneal rupture, contrast extravasation is limited to the pelvic extraperitoneal space. In complex extraperitoneal rupture, contrast extravasation extends beyond the prevesical space into the thigh, scrotum, or perineum, implying a fascial boundary injury (32,33). Treatment is usually nonsurgical catheter drainage. This approach is unlike intraperitoneal bladder rupture, which requires surgical management. With intraperitoneal rupture (25% of major bladder injuries), the irritative effect of urine exposed to the large surface area of the peritoneum can cause rapid development of chemical peritonitis, which complicates the patient’s clinical management. Intraperitoneal bladder rupture is generally considered a surgical emergency necessitating urgent primary repair of the bladder wall (32,33). Occasionally, combined bladder ruptures occur with both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal components (12% of bladder injuries).

Although conventional cystography has been used to evaluate for bladder injury, CT cystography has been shown to be more accurate and often integrates more easily into the trauma patient’s evaluation.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Extraperitoneal bladder rupture demonstrates flamelike, infiltrating contrast extravasation and is generally managed conservatively.

Intraperitoneal bladder rupture shows smooth, freeflowing contrast outlining bowel and other intraperitoneal structures, and is managed surgically.

Case 13.12

HISTORY: A 25-year-old African American male with sickle cell trait presents with hematuria and right flank pain

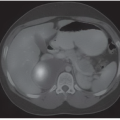

FINDINGS: A contrast-enhanced axial CT image of the abdomen (Fig. 13.12.1) demonstrates diffuse, ill-defined mass-like enlargement of the right kidney with heterogeneously decreased enhancement but no change in reniform shape.

DIAGNOSIS: Renal medullary carcinoma

DISCUSSION: Renal medullary carcinoma represents a very rare renal tumor that occurs almost exclusively in African American patients with sickle cell trait. The most common imaging presentation is a centrally located, infiltrative renal mass with preservation of normal renal contours. In addition, this particular renal tumor is extremely aggressive and commonly has metastatic involvement of lymph nodes, liver, and lungs at the time of presentation. As expected, prognosis is very poor with a majority of patients living <4 months after diagnosis. Thankfully, the diagnosis is rare with <100 documented cases in the US. (34,35).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Although a rare diagnosis, the constellation of a young African American patient with sickle cell trait who presents with hematuria, flank pain, and a central, infiltrative renal mass highly suggests the diagnosis of renal medullary carcinoma.

Case 13.13

HISTORY: A 62-year-old female with a history of diabetes mellitus presents with right flank pain and dysuria

FINDINGS: Axial contrast-enhanced CT (Fig. 13.13.1) depicts gas in the right renal pelvis. The urothelium is thickened, and the right kidney is asymmetrically enlarged with decreased enhancement and a somewhat patchy nephrogram.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree