Abstract

Hydatid disease, caused by Echinococcus granulosus , is a parasitic infection that primarily affects the liver but can also involve other organs, including the spleen, kidney, and peritoneum. This case series examined 9 patients with hydatid cysts, highlighting their clinical presentations, radiological findings, and management strategies. This study analyzed 9 patients diagnosed with hepatic and extrahepatic hydatid cysts. Comprehensive evaluations were performed for all patients, including clinical history and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) imaging. The cases included cystic lesions in the liver (7 patients), spleen (3 patients), kidney (2 patients), and peritoneum (1 patient). Typical radiological features, such as the “double-wall sign,” daughter cysts, and peripheral calcifications, were observed. The management strategies varied from surgical excision to medical therapy with albendazole. Hydatid disease presents diverse clinical and radiological features. Early diagnosis using advanced imaging techniques and a multidisciplinary approach is critical for effective management and prevention of complications.

Background

Hydatid disease, also known as cystic echinococcosis, is a parasitic infection caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus or, less commonly, Echinococcus multilocularis . It remains a significant public health concern in regions where livestock farming and close human-animal interactions are common. These include areas such as the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, Central Asia, South America, and sub-Saharan Africa [ , ]. The parasite lifecycle involves canines as definitive hosts and livestock as intermediate hosts, with humans acting as accidental hosts when they ingest parasite eggs from contaminated food or water [ , ]. Once inside the human body, eggs hatch into larvae, which then migrate via the bloodstream to the liver (70%-80% of cases) and lungs (10%-15%). Other less commonly affected organs include the spleen, kidneys, brain, and peritoneum [ ]. The disease often progresses silently, with cysts growing slowly over the years before the clinical symptoms manifest. Larger cysts or cysts in critical anatomical locations can lead to significant complications, including rupture, secondary infection, or compression of adjacent structures [ ].

The clinical presentation of hydatid disease is variable, depending on cyst size, location, and stage of development. Liver involvement often presents as right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, or jaundice in cases of bile duct compression [ ]. Extrahepatic involvement can lead to a wide spectrum of symptoms, such as flank pain in renal cysts or abdominal distension in peritoneal diseases. Although rare, splenic hydatid cysts may present with left upper quadrant discomfort or splenomegaly [ ]. Early diagnosis of hydatid disease relies heavily on imaging modalities. Ultrasonography is widely used because of its availability and sensitivity for identifying cystic lesions, particularly hepatic hydatid cysts. It provides essential information on cyst structure, wall thickness, and the presence of daughter cysts or hydatid sand [ ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification system categorizes cysts into active, transitional, and inactive stages based on ultrasound characteristics [ ].

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide detailed anatomical information and are indispensable for detecting extrahepatic involvement. In particular, CT imaging is preferred for identifying cyst calcifications, internal septations, and complications, such as rupture or infection. The characteristic “double-wall sign” on CT is highly specific for hydatid cysts [ ]. MRI is useful in assessing soft tissue involvement and distinguishing hydatid cysts from other cystic lesions, such as neoplastic or congenital cysts [ ]. Serological tests, including enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and indirect hemagglutination, are adjunctive tools that detect antibodies against E. coli antigens. However, sensitivity can vary depending on the location and stage of the cyst. False-negative results are more common for extrahepatic or calcified cysts [ , ].

HD treatment of hydatid disease is multidisciplinary, encompassing medical, surgical, and minimally invasive approaches. Albendazole and mebendazole, the primary antiparasitic agents, are used as first-line therapies, particularly for small cysts or inoperable cases. These drugs disrupt the microtubular structure of the parasite, leading to cyst degeneration over time [ ]. However, medical therapy alone is often insufficient for larger cysts or those that cause complications. Surgical intervention remains the cornerstone for the management of complicated hydatid cysts, particularly in the liver. Techniques such as cystectomy or pericystectomy aim to remove the cyst while preserving surrounding healthy tissue. Minimally invasive procedures such as percutaneous aspiration, injection, and re-aspiration (PAIR) have gained popularity for uncomplicated cases, offering lower morbidity rates than open surgery [ ]. PAIR involves aspirating cyst contents under ultrasound guidance, injecting a scolicidal agent (e.g., hypertonic saline), and re-aspirating debris to sterilize the cyst cavity [ ].

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, recurrence rates remain a significant concern, particularly in endemic regions. Long-term follow-up with imaging and serological testing is essential to monitor recurrence or residual disease [ , ]. Public health measures, including deworming of domestic animals and public education on food hygiene, play a critical role in reducing the incidence of hydatid disease.

Case presentation

Case 1

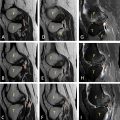

A 40-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of acute abdominal pain, which had an abrupt onset and radiated to the back. The patient also reported a history of fever for 3 weeks. There were no associated symptoms, such as cough, cold, loss of consciousness, seizures, or bowel and bladder disturbances. She had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus for the past 10 years, but had no other significant medical or surgical history. No abnormalities were evident on the clinical examination. Radiological evaluation using noncontrast CT of the abdomen revealed a well-circumscribed, unilocular, nonenhancing cystic lesion in the spleen. The lesion displayed the characteristic “double-wall sign,” which is a hallmark feature of hydatid cysts. This finding led to the diagnosis of splenic hydatid cyst, an uncommon presentation of hydatid disease ( Fig. 1 ).

Case 2

A 72-year-old male presented with complaints of abdominal distension lasting 2 months, along with recent onset of loss of appetite and fever for 6 days. The patient also experienced constipation for 1 week. The patient denied any symptoms such as cough, cold, seizures, or bowel and bladder disturbances. His medical history was notable for hypertension, which was diagnosed 11 years ago. The patient had no other comorbidities. Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) of the abdomen revealed an enlarged liver with multiple well-defined cystic lesions, predominantly in the left hepatic lobe. These cysts showed partially calcified walls, daughter cysts, and enhanced internal septation. The largest cysts were located in segments VII and VIII of the liver. These imaging features were consistent with those of multilocular hepatic hydatid cysts ( Fig. 2 ).

Case 3

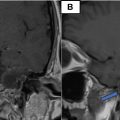

A 32-year-old male presented with a 6-month history of persistent right-flank pain. He denied systemic symptoms, such as fever, vomiting, or seizures, and there were no associated bowel or bladder complaints. The patient had no significant medical or surgical history and no known comorbidities. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a large, well-defined, multiseptate exophytic cystic lesion involving the upper, middle, and lower poles of the right kidney. The lesion had a thick peripheral enhancing wall with calcific foci and extended superior to the inferior surface of the liver. The findings were diagnostic of an isolated renal hydatid cyst, a rare extrahepatic manifestation of hydatid disease ( Fig. 3 ).

Case 4

A 36-year-old female presented with progressive abdominal pain for 6 months. The pain was nonradiating, and the patient denied any history of trauma, fever, vomiting, or bowel and bladder disturbances. Her medical history was unremarkable and there had no known comorbidities. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a well-defined cystic lesion with folded membranes and peripheral calcifications in segment VIII of the liver, consistent with a hydatid hepatic cyst. Additionally, another cystic lesion containing multiple daughter cysts and hydatid sand was observed in the peritoneum, located in the gastrosplenic region, compressing the left kidney and pancreas. These findings suggested the presence of both hepatic and peritoneal hydatid cysts ( Fig. 4 ).

Case 5

A 58-year-old male shepherd reported abdominal distension that persisted for 5 years, accompanied by acute abdominal pain for 2 months. He also experienced fever and vomiting for 5 days. The patient had no bowel or bladder complaints, significant medical history, or comorbidities. CECT imaging revealed extensive multiloculated cystic lesions involving the liver, spleen, and peritoneal cavity. These cysts had peripheral enhancing walls and internal septations, with multiple daughter cysts within the larger “mother cysts.” A hypodense lesion with calcification was observed in liver segment VI. Imaging findings confirmed disseminated hydatid disease involving multiple organs ( Fig. 5 ).