Pelvic pain syndromes are common and often neuropathic, with pudendal neuralgia being the most recognized. However, other nerves from the sacral and lumbar plexus—including the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, and posterior femoral cutaneous branches—may also contribute to pelvic and genital neuropathic pain. Diagnosis is challenging due to complex pelvic neuroanatomy and overlapping etiologies. MR neurography plays a key role in evaluating affected nerves and musculoskeletal structures, with advanced sequences improving vascular suppression and nerve conspicuity. While ultrasound and CT mainly guide interventions, MR-ultrasound fusion imaging and MR neurography-guided perineural injections provide more accurate, image-guided treatment strategies.

Key points

- •

The pelvis contains intricate nerve networks; thorough knowledge of pelvic neuroanatomy is crucial for accurately diagnosing and treating various pelvic pain syndromes.

- •

High-resolution MR neurography complements clinical evaluation, as it allows for the analysis of pelvic nerve pathways and identification of other potential pain contributors.

- •

Pudendal neuralgia is common, but pelvic neuropathic pain may also involve genital or perineal branches of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, or posterior femoral cutaneous nerves.

- •

Imaging-guided techniques, especially real-time MR-ultrasound fusion and MR neurography-guidance, provide a highly accurate alternative for perineural injections.

| ADC | apparent diffusion coefficient |

| ASIS | anterior superior iliac spine |

| CT | computed tomography |

| CPP | chronic pelvic pain |

| DW | diffusion-weighted |

| GFN | genitofemoral nerve |

| IHN | iliohypogastric nerve |

| IIN | ilioinguinal nerve |

| MR | magnetic resonance |

| PFCN | posterior femoral cutaneous nerve |

| SN | sciatic nerve |

| SPAIR | spectral adiabatic inversion recovery |

| T1W | T1-weighted |

| T2W | T2-weighted |

| US | ultrasound |

| 3D | 3-dimensional |

Introduction

The pelvis is a complex region with intricate neuroanatomy, containing both somatic and autonomic (sympathetic and parasympathetic) nervous systems making pain diagnosis in this region extremely challenging. The most important nerve groups include the lumbosacral plexus, from which emerge the sciatic, superior, and inferior gluteal, pelvic splanchnic, pudendal, and posterior cutaneous nerves, as well as the nerves to the quadratus femoris, levator ani, piriformis, and obturator internus. Additionally, the inferior hypogastric plexus and the sensory branches of the lumbosacral plexus, including the iliohypogastric nerve (IHN), the ilioinguinal nerve (IIN), and the genitofemoral nerve (GFN), play key roles in pelvic innervation.

The estimated global prevalence of pelvic pain ranges from 2% to 30% of people worldwide, being more frequent in women than men. , Pelvic pain syndromes involve chronic pelvic pain (CPP), defined as disabling and persistent pain lasting at least 3 to 6 months. CPP is frequently associated with negative cognitive, behavioral, sexual, and emotional effects, along with symptoms related to lower urinary tract, sexual, bowel, pelvic floor, or gynecologic dysfunction. CPP often has multiple causative factors. Pain can generally be classified as visceral, somatic, or neuropathic, and these etiologies frequently overlap. Due to the chronic nature of CPP, patients often develop both peripheral and central sensitization. One of the most underrecognized causes of CPP is neuropathic pain, such as pudendal neuralgia, affecting approximately 4% of CPP patients. However, its true prevalence may be underestimated due to diagnostic challenges, with reported delays in diagnosis ranging from 2 to 10 years. Neuropathic pain is typically—but not exclusively—burning, aching, or shooting in nature, and presents with hyperesthesia, dysesthesias, and allodynia, following a dermatomal distribution. , Pudendal neuralgia is a disabling form of perianal, perineal, and/or genital pain caused by nerve injury, entrapment, or traction. However, other nerves from the sacral and lumbar plexus, such as the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, genitofemoral, inferior cluneal, and perineal branches of the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve, may also contribute to neuropathic pelvic and/or genital pain. , Spinal pathology or any condition affecting the course of these nerves can lead to neuropathic pain. Etiologies such as neoplastic disease, infection, trauma, surgical incisions, or postoperative scarring can result in nerve injury or entrapment. However, in many cases, no specific cause is found, and the condition is labeled idiopathic.

Specific syndromes

Pudendal Nerve

Anatomy

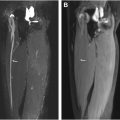

The pudendal nerve is a sensory and somatic nerve originating from the ventral rami of the second to fourth (and occasionally fifth) sacral nerve roots. The S3 and S4 sacral nerve roots exclusively innervate the genito-anal regions, while S2 contributes to both the pudendal and sciatic nerves (SNs). After branching from the sacral plexus, the pudendal nerve courses laterally and inferiorly along the anteroinferior border of the piriformis muscle, passing through the infrapiriformis foramen. It exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic notch, posterior to the SN, enters the gluteal region above the sacrospinous ligament, re-enters the pelvis between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments, and travels through Alcock’s canal under the internal obturator muscle fascia, accompanied by the internal pudendal vessels, to reach the perineum ( Fig. 1 ).

The pudendal nerve gives rise to 3 branches containing sensory (50%), motor (20%), and autonomic (30%) fibers. It provides sensory innervation to the external genitalia and perineal skin, and motor innervation to the external urethral sphincter, external anal sphincter, levator ani, and skeletal muscles of the perineum. These branches include the inferior rectal nerve, the superficial and deep perineal nerves, and the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris. However, pudendal nerve anatomy is highly variable; there may be 2 or even 3 pudendal nerve trunks, all entering above the sacrotuberous ligament (with the rectal nerve sometimes passing through it), and 2 exiting from Alcock’s canal—one for the dorsal branch and one for the perineal branch. , These variations have important implications for diagnostic nerve blocks and surgical intervention strategies.

Muscles innervated by the pudendal nerve or located along its pathway may contribute to pain. The pudendal nerve lies adjacent to the piriformis, ischiococcygeus (coccygeus), and internal obturator muscles. Injuries to these structures or hypertrophy of the internal obturator muscle can contribute to pudendal neuralgia. Additionally, the pudendal nerve, along with other nerves of the sacral plexus, innervates the levator ani muscle, which consists of 3 muscles: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis.

Sites of entrapment

The pudendal nerve may be damaged, irritated, or compressed along its course from the sacral nerve roots (S2–S4) to its distal location beneath the fascia of the internal obturator muscle in Alcock’s canal. Six potential regional zones along its anatomic path have been proposed where the pudendal nerve can become injured: within the pelvis below the piriformis muscle, in the space between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments, at the entrance to Alcock’s canal (and while passing the falciform process, an internal extension of the sacrotuberous ligament), inside Alcock’s canal, at the inferior pubic ramus canal, and along the extrapelvic pathway adjacent to the pubic symphysis. , Causes of pudendal neuralgia include nerve compression from activities such as cycling or prolonged sitting, trauma, iatrogenic nerve damage after surgical procedures in the perineal region leading to neurogenic inflammation, stretching of the nerve during delivery, tumors, nonencapsulated lipomas in the ischiorectal fossa, and inflammatory, infectious, or autoimmune disorders. Additionally, the pudendal vessels, which can be large and may be tortuous or dilated, can compress the nerve.

Clinical presentation of the pudendal neuralgia

The 5 Nantes criteria—4 clinical (neuropathic pain in the pudendal nerve’s sensory area, worsened by sitting, no nighttime awakening, no objective sensory deficit on examination) and 1 invasive (positive response to local anesthetic injection at the ischial spine)—are diagnostic for pudendal nerve entrapment. , If these criteria are not met, the nerve may still cause pain, but for reasons other than entrapment. Pudendal neuralgia often overlaps with other pelvic pain causes, such as myofascial pain or other neuropathies, including inferior cluneal nerve involvement in 25% of cases. No other supplementary test can definitively confirm or exclude the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia. Perineal electrophysiological studies (electromyography and nerve conduction studies) are not specific enough to be routinely recommended, because they only investigate large motor fibers and may not detect selective lesions of small sensory fibers. However, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the pelvis is recommended to evaluate and rule out other potential causes of both neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain.

Imaging findings

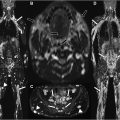

Ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT) are primarily limited to guiding diagnostic injections with anesthetics to confirm clinical suspicion of pudendal neuralgia. MR imaging serves as a complementary tool to rule out differential diagnoses. Specific MR neurography sequences should be used to evaluate nerves and related musculoskeletal structures that may be implicated in cases of neuropathic CPP. High-resolution T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) sequences with uniform fat suppression, utilizing spectral adiabatic inversion recovery (SPAIR) or modified Dixon techniques, as well as diffusion imaging that provides vascular signal suppression, are recommended. Regarding diffusion-weighted (DW) MR neurography, conventional single-shot echo-planar imaging (ss-EPI) provides relatively low spatial resolution and is prone to blurring and distortion, particularly in areas with tissue-air interfaces like the pelvis, compromising visualization of peripheral nerves. Readout-segmented echo-planar imaging is a promising method for selectively visualizing pelvic nerves.

The 3-dimensional (3D) imaging techniques, such as the 3D SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application-optimized Contrasts using different flip angle Evolutions) sequence, have limitations in evaluating the pudendal nerve due to its small size and incomplete venous signal suppression, even with motion-sensitive driven equilibrium pulses. The double echo steady-state sequence offers high-resolution images for morphologic nerve assessment but peripheral nerves are difficult to distinguish from vasculature with this sequence. Other 3D MR neurography sequences, such as 3D DW-reversed fast imaging with steady-state free precession (PSIF) and 3D NerveVIEW with gadolinium contrast, enhance vascular suppression, improve nerve-to-tissue contrast, and have demonstrated a better visualization of nerves and their branches. ,

Diffusion tensor imaging with MR tractography provides 3D visualization of nerve pathways and may offer new insights for managing pudendal neuralgia due to entrapment. Initial results suggest that MR tractography is promising and potentially superior to MR neurography for diagnosing intrapelvic lumbosacral plexus entrapments, despite minimal differences in fractional anisotropy (FA) or apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) compared with controls. However, evaluating the pudendal nerve presents limitations due to its small size—particularly below the ligamentous clamp formed by the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments—its complex anatomic course, and the need for numerous diffusion gradients or smaller voxel sizes, which result in longer acquisition times and increased susceptibility to artifacts. , Prospective studies in healthy subjects and patients are needed to refine acquisition parameters and validate MR tractography’s accuracy for diagnosing pudendal neuralgia and other intrapelvic nerve entrapments.

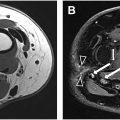

The pudendal nerves are best seen on axial images at the distal edge of the piriformis muscle as they enter the interligamentous space at the ischial spine. Distal perineal branches can be difficult to identify due to their small size and the presence of pelvic veins , ( Fig. 2 ).

Abnormal fascicular morphology of the nerve and increased signal intensity on T2W, DW, and ADC MR images may indicate nerve injury. However, in chronic stages where these MR findings may be absent or when the anatomy is altered, it is essential to search for indirect signs, such as thickening of the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments, fibrous lesions, thickening of the internal obturator muscle fascia, fractures, tumors and injuries to other nerves, as well as conditions such as adjacent muscular lesions, piriformis syndrome, and ischial bursitis.

At the level of the sacrum and infrapiriformis foramen, pudendal neuralgia can be caused by piriformis muscle spasm, direct trauma, tumors or tumor-like conditions, infections, vascular, fibrous, metabolic, inflammatory, or autoimmune processes. In this location, pudendal neuralgia often presents with mixed neuropathic pain due to the involvement of other nerves from the lumbosacral plexus ( Fig. 3 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree