Traumatic injury is one of the leading causes of emergent hospital evaluations. Specifically, blunt bowel and mesenteric injury (BBMI) account for 1% to 5% of abdominal traumas with a high morbidity and mortality, as clinical signs and nonspecific imaging findings make the initial diagnosis challenging. Understanding key imaging findings and the clinical symptoms can increase the radiologist’s suspicion for BBMI and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Key points

- •

Blunt bowel and mesenteric injury (BBMI) portends high morbidity and mortality.

- •

BBMI is a challenging imaging diagnosis and should be assessed with clinical signs and symptoms.

- •

Dual energy computed tomography (CT) has improved CT trauma protocol technique in aiding diagnosis of BBMI without significantly altering examination duration or radiation dose.

Introduction

Traumatic injury is one of the leading causes of emergent hospital evaluation in the United States. Unintentional injury is the third leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for 68.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals annually. In 2021, unintentional injury accounted for 63.7% of emergency hospital visits out of all unintentional injury visits in the United States. Patients with traumatic injuries are immediately brought to the emergency department where they are assessed for hemodynamic stability and life-threatening injuries by the trauma service per standardized advanced trauma life support protocol. , This standard protocol, along with clinical status and bedside radiologic evaluation with focus assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST), guides the initial decision for surgical intervention. Alternatively, patients with a negative FAST who appear clinically stable are often taken to computed tomography (CT) imaging for a more comprehensive and detailed assessment of traumatic injuries that may necessitate surgical intervention.

The abdomen is the third most common location for blunt trauma. Solid organ injury involving the spleen and liver accounts for the most common blunt intra-abdominal injuries. Evaluation of solid organ injury is standardized with the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma criteria allowing for a universal radiologic assessment to help guide surgical management. The standardized evaluation increases the radiologist’s awareness in identifying traumatic injury to the solid organs during immediate real-time diagnosis with the trauma surgeons. The characterization of traumatic bowel and mesenteric injury, on the other hand, has no standardized assessment and is more challenging to diagnose. While less common than hepatic or splenic injury, bowel and mesenteric injury accounts for 1% to 5% of trauma-related injuries. , Early identification of subtle injuries to the bowel and mesentery is critical in preventing morbidity and mortality. A delay in diagnosis of mesenteric injury by as brief as 8 h can result in a significant increase in morbidity and mortality, lengthening stays in the intensive care unit, and worsening patient prognosis due to the risk for sepsis. , ,

Blunt bowel and mesenteric injury (BBMI) is both clinically and radiologically difficult to diagnose. During initial clinical evaluation in the emergency department, patients may not have external signs of injury, physical examination findings may be obscured by distracting injuries, and clinical findings for bowel injury like peritonitis or guarding can take hours to become apparent. Moreover, radiologists are in a challenging position for diagnosing these injuries on real-time scans given concurrence with multiple intra-abdominal injuries, evaluation of multiple segments of compressed bowel and subtle nonspecific findings. Our discussion focuses on key imaging findings related to BBMI to increase radiologist awareness during initial diagnostic evaluation.

Computed tomography

CT is the mainstay for the evaluation of clinically stable trauma patients. Identification of BBMI substantially relies on adequate protocol technique. When trauma patients undergo CT imaging, key considerations include protocol, examination duration, and the use of contrast agents to optimize the accurate identification of bowel injury. CT is diagnostically superior to other imaging modalities in the emergency setting. It provides a high specificity but lower sensitivity for identifying BBMI. , In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, authors Hsia and colleagues found that pooled sensitivity of CT was 67.8% while the specificity was 96.9% for the identification of hollow viscus injury after blunting abdominal trauma. In addition, CT imaging is expeditious without the safety precautions and examination duration that limit the use of MR imaging in the emergency setting.

Maximizing CT protocols for the quick and timely evaluation of trauma patients is critical for early identification of blunt BBMI, but also must be time-sensitive given the tentative clinical status of these patients. Although there is no standard recognized CT protocol for trauma patients, there are generally two predominantly accepted methods, which include whole-body CT angiography or a segmented CT protocol. Whole-body CT angiography involves a single pass from the vertex to the pelvis in the arterial phase, which generally is short in duration and limits radiation exposure, while a segmented protocol focuses on scanning the chest in the late arterial phase to include the liver and spleen followed by a portal venous phase from the lung bases to the lesser trochanters. ,

Technique

Trauma CT scans use multiphase imaging with intravenous (IV) contrast to assess bowel injury and contrast extravasation. At our institution, we use a segmented protocol specifically designed for the type of trauma and suspected injuries. The protocol consists of either 2- or 3-phase scans on a 64-slice multidetector CT. We obtain contiguous 1.25-mm axial sections from the lung bases through the base of the liver after administration of 100 mL of IV contrast with a 30s delay at an injection rate of 3 cc per minute. This is followed by a second acquisition from the diaphragm to the greater trochanters after a 70-s delay for the portal venous phase. Finally, an optional third acquisition is obtained at 5 min from the diaphragm to the greater trochanters at the radiologist’s discretion. A pitch of 1.234:1 is used with 40 mm detector coverage with a peak kilovoltage of 120 kVp. Reconstructions are made in the sagittal and coronal planes of each acquisition. All of our images are obtained on a dual-energy CT (DECT) scanner, providing additional sequences that can aid the diagnostician including virtual noncontrast, calcium suppression, monoenergetic (40 keV), and high keV reconstructions.

Noncontrast

Noncontrast sequences at the time of examination are generally deferred since they increase the examination duration and radiation dose without significant contribution to the imaging findings, especially given the advent of virtual noncontrast reconstructions in DECT. This reconstructed sequence can be used for evaluation of bowel wall hematomas, confirm active contrast extravasation, or differentiate intraluminal enteric contents and calcifications without increasing the examination duration or radiation dose. ,

Oral Contrast

The use of oral contrast is another consideration especially when evaluating blunt bowel injuries. Currently, there is no proven benefit for the use of oral contrast agents in the emergency setting as CT with IV contrast alone is diagnostic for BBMI. , In a recent study by Golikhatir and colleagues , the authors compared the use of IV contrast versus IV and oral contrast in the assessment of blunt abdominal trauma and found that the sensitivity and specificity were similar, with sensitivities of each approximately 96% and specificities around 92%. Given the similarity in results of IV and oral contrast, oral contrast agents are deferred since they have a high risk of aspiration and increase the examination duration. Prior studies, including Stuhlfaut and colleagues , also confirmed that CT alone without oral contrast is adequate to identify bowel and mesenteric injuries.

Pathophysiology

The most common etiologies for BBMI include motor vehicle collision, physical assault, sports activities, and falls from a height. , 70% to 80% of blunt bowel injuries occur in the small bowel, 5% to 20% in the colon, and 10% in the duodenum. , Understanding the most common locations for injury and the underlying mechanisms related to these locations can improve diagnostic assessment in real-time.

BBMI results from 3 common mechanisms: shear, crush, and burst injury. , A shear injury arises from the location of mobile bowel segments alongside fixed non-mobile structures. At the ligament of Treitz, for instance, the retroperitoneal duodenum is adjacent to the freely moving proximal jejunum. Similarly, the ileocecal valve is where the distal ileum is fixed to the colon. When a rapid deceleration force occurs at these sites, there is a higher risk for shearing, which may lead to bowel laceration, mesenteric tears, and vascular injury causing hemorrhage and infarction. , ,

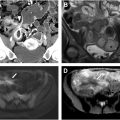

Crush injury results from compression of the bowel from an external force. , Seatbelts, dashboard injuries, or steering wheels are known forces that can compress the bowel against the spine. , Bowel compression can lead to hematomas, lacerations, and contusions with devascularization increasing the risk for bowel ischemia ( Fig. 1 A, B).

Lastly, bowel loops can have a rapid increase in intraluminal pressure resulting in burst injury. Burst injuries occur due to high intraluminal pressure causing full-thickness bowel perforations, classically within compressed or closed-off loops of bowel. Patients are predisposed to burst injuries if they have underlying pathology that increases the baseline intraluminal pressure, such as Crohn disease, ileus, or a pre-existing bowel obstruction. The force required to incur burst bowel injury is usually less than that of shear or crush injuries, and thus bowel injury can often be seen in isolation with this mechanism. These injuries usually occur in the small bowel, notably the proximal jejunum.

Dignostic signs of bowel and colonic injury

Unfortunately, the more specific signs have a lower sensitivity, and the more sensitive signs have lower specificity, which creates a diagnostic challenge for the radiologist. Therefore, careful consideration of the mechanism of injury and a combination of the following diagnostic signs can increase the radiologist’s suspicion and localization of blunt BBMI alongside clinical assessment.

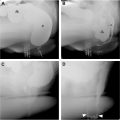

Highly specific diagnostic signs of bowel and colonic injury

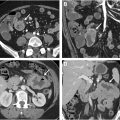

Bowel wall discontinuity in the setting of blunt abdominal injury is 100% specific for bowel injury, although it is not commonly seen overtly on CT. Bowel wall discontinuity is defined as a full-thickness defect of the bowel wall ( Fig. 2 A–D). Unfortunately, this finding has low sensitivity as bowel perforations are often too small for accurate detection by CT. Hypoenhancement of the bowel wall and spillage of enteric contents can help localize the injury site. Irregular circumferential enhancement can be seen in which an abnormally thickened loop of bowel has focal hypoenhancement along 1 margin of its circumference. The diagnostic Janus sign, with etymology arising from the dual-faced Roman god Janus representing transitions, is characterized by abrupt demarcation between devascularized hypoattenuating bowel and adjacent perfused hyperattenuating bowel ( Fig. 3 A, B). Additionally, DECT can prove helpful in exaggerating the attenuation differences between normally enhancing bowel wall and hypoenhancing injured bowel wall (see Fig. 2 ). Bowel wall discontinuity can also be diagnosed by active oral contrast extravasation; however, most institutions no longer include administration of oral contrast in their trauma protocol.

Extraluminal spillage of enteric contents is 100% specific for full-thickness bowel wall injury. The radiographic appearance of enteric contents differs depending upon their stage of digestion and can be a useful tool in localizing the site of bowel injury. Gastric contents are less digested and can appear as full food particles with interspersed gas. Small bowel contents are more digested and radiographically are fluid density with minimal gas. Colonic enteric contents are fecalized, presenting as a mottled mixture of solid food particles, fluid, and gas. In the era of oral contrast administration during trauma scans, free intraperitoneal oral contrast was 100% specific for bowel perforation.

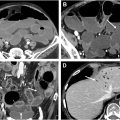

The presence of extraluminal air is highly suggestive of bowel perforation in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma with a specificity of 95%. Unfortunately, this sign has low sensitivity ranging from 18% to 32% and is seen in only about one-third of patients with confirmed surgical full-thickness bowel tears. Free air can be intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal, aiding in localization of injury to intraperitoneal bowel versus retroperitoneal duodenum or segments of the colon ( Fig. 4 A, B).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree