This review discusses the ways in which the health care provider (or more broadly, the provision of medical care) can cause harm to the bowel and highlights the appearance of such untoward events on imaging. The etiologies are myriad, and as such, the radiologist must remain vigilant in identifying the presence of suspected and unsuspected injuries. Specific attention is given to complications from medication and external radiation therapy, as these interventions and their timing are often not known by the radiologist.

Key points

- •

Iatrogenic bowel injuries are uncommon, but given the sheer number of treatments and interventions, are frequently encountered on imaging.

- •

Iatrogenic bowel injuries may follow diagnostic or interventional procedures, as well as nonprocedural interventions, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other medication administration.

- •

The radiologist must remain vigilant in identifying and characterizing iatrogenic bowel injuries to allow for prompt, appropriate care, as they may be the first to suspect and identify such injuries.

Introduction

The term “iatrogenic” encompasses the undesirable pathologies that arise from an attempt at healing. Its definition of: “Induced unintentionally by a physician or surgeon or by medical treatment or diagnostic procedure” is almost always limited to the negative consequences of treatment. This term does not include harm from other unintentional, nonmedical causes and/or self-harm.

Iatrogenic bowel injuries are uncommon but are becoming more frequently detected by the radiologist due to increasing utilization of medical imaging. When these injuries are clinically suspected, the radiologist confirms the diagnosis and characterizes the extent of injury. Many injuries are detected on imaging before becoming clinically apparent, making the radiologist important in the immediate postprocedural period where imaging may detect unexpected injuries to the bowel. Perhaps even more important, changes to bowel from novel chemotherapy or other medications may be subtle but detection can allow for therapy change and mitigation of injury. These nonprocedural injuries to bowel—without the clear inciting event of surgery, percutaneous intervention, or endoscopy—can catch the radiologist unaware. In all cases of iatrogenic bowel injuries, the radiologist must be meticulous and attentive to enable early diagnosis and avoid subsequent morbidity and mortality.

This review discusses the ways in which the health care provider (or more broadly, the provision of medical care) can cause harm to the bowel and highlights the appearance of such untoward events on imaging.

Procedural injury

Not unexpectedly, the largest portion of recognized iatrogenic bowel injuries occurs during interventions by surgical/interventional teams, including open, laparoscopic, percutaneous, or endoscopic procedures. Accurate data concerning these complications is hard to come by, largely because of issues with standardized reporting and lack of a national database to track these events. If a bowel injury is recognized intraoperatively, it is likely not flagged the same way as an iatrogenic bowel injury detected on imaging after surgery. Moreover, there is great variability of risk of injury between interventions that is dependent upon many factors, including the experience of the provider, the specific intervention performed, and the comorbidities of the individual patient. The sheer number and types of interventions further compounds the complexity of quantifying these injuries. As such, the true incidence of postprocedural injury is unknown. This makes identifying the most common injuries or stratifying risk factors for injury difficult.

Risk Factors

Not surprisingly, prior abdominal surgery and its resulting adhesions are associated with iatrogenic injury to the bowel during open, laparoscopic, and endoscopic interventions. When adhesiolysis is required, enterotomies and seromuscular injuries both increase. A review by Khoury and colleagues reviewed 15,133 abdominal operations (9674 open and 5459 laparoscopic) and identified 32 patients (0.02%) as missed “inadvertent gastrointestinal tract injuries.” Of these patients, 84% had adhesions and 63% had undergone prior abdominal surgery.

All surgeries and interventions have specific risk factors for bowel injury and common sites of bowel injury. For example, colonic perforations from barium enema and computed tomographic (CT) colonography are rare, estimated to occur approximately 0.009% to 0.06% and 0.1% to 0.9%, respectively. There is an increased risk in patients with underlying inflammatory bowel disease, steroid use, malignancy, infection, prior radiation, prior bowel necrosis, or preexisting partial tear. Additional reported risk factors for perforation from colonoscopy include advanced colonoscopy technique, age greater than or equal to 70 years of age, inpatient status, low body mass index, and sedation status. These same risk factors reasonably may all play a role in elevating the risk of bowel injury in other interventions. Depending on intervention and the published report, obesity, malignancy, or prior radiotherapy to the abdomen and pelvis are commonly noted as increasing the risk of bowel injury.

Diagnosis and Timing of Diagnosis

In a meta-review of 329,935 laparoscopic procedures, the time of iatrogenic bowel injury was reported in only 250 patients. Two-thirds of injuries were discovered “early” (during or directly after surgery); while most of the remaining cases were diagnosed within 48 hours of laparoscopy. Ten percent of injuries were diagnosed “late,” occurring several days after surgery. Most of these were attributed to thermal injury. Estimates of “early” versus “late” bowel injuries are very opaque in the literature. Unlike van der Voort, many authors characterize “early” injuries as detected in the operating room; and “late” as after, further confounding data review. In general, patients diagnosed with bowel injury after leaving the operating room suffer significantly worse outcomes than those found intraoperatively.

Imaging and Bowel Injury in Open and Laparoscopic Procedures

The mobile bowel, occupying a large portion of the abdominopelvic cavity, has been reported as injured in 0.1% to 9.2% of intra-abdominal surgeries. The aforementioned meta-review of laparoscopic procedures found an incidence of gastrointestinal perforation of 0.22%. Approximately 40% of bowel injuries were related to introduction of the access needle or trocar, while 25.6% of injuries occurred during cautery. In the cases where the site of injury was reported, the small bowel was injured more commonly than the colon (55.8% vs 38.6%), with the duodenum injured 9% of the time (all during laparoscopic cholecystectomy). A recent review of minimally invasive surgeries reported that 0.27% of patients had a bowel injury due to initial port placement. Elsewhere in the abdomen and pelvis, the bowel closest to the region of intervention is often most injured, though the radiologist cannot isolate the search pattern to an individual location, as any part of the bowel may be injured, and the exact surgical technique is often not known at the time of image interpretation.

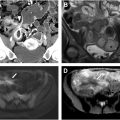

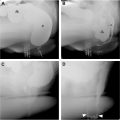

There is overlap between the imaging findings of “normal postoperative state” and the pathologic, iatrogenic injury after surgery. For example, the most salient finding of iatrogenic bowel injury is likely to be a persistent postoperative ileus, but this is a common finding in a postoperative patient. Free intraperitoneal gas, fluid collections, and peritoneal enhancement are commonly seen in the postoperative setting ( Fig. 1 A, B ). Pneumoperitoneum has been reported to be present on 87% of CTs and 53% of radiographs taken 3 days after surgery and 50% of CT and 8% of radiographs obtained 6 days after surgery. Extraluminal positive contrast material is diagnostic of perforation ( Fig. 2 A, B ), though this is not a sensitive finding, as has been shown in other cases of penetrating trauma to the bowel. Bowel injury during laparoscopic intervention may go undetected at the time of surgery and not manifest itself for several days. Other findings on imaging are dependent on many factors, including site and size of the injury and time since injury. Mesenteric or retroperitoneal gas should raise concern for perforation especially if that mesentery was not known to be involved with the surgery. Free intraperitoneal gas that does not decrease (or increases) over time or which is isolated in proximity to abnormal bowel loops should be considered at time of evaluation to be suspicious for occult perforation. The bowel should routinely be interrogated for focal thickening, focal defect, or focal nonenhancement.

Injury from Percutaneous Intervention

Percutaneous interventions offer minimally invasive approaches for diagnosis and management of a wide range of medical conditions. These procedures include solid organ interventions such as biopsy and ablation as well as the placement of enteral, biliary, and urinary tubes and stents. These interventions carry the risk of bowel injury which can arise from a variety of factors including proximity of the target organ to the bowel, anatomic variations, or inadvertent needle or catheter placement. For example, bowel injury during percutaneous kidney surgery occurs in less than 1% of cases and most commonly involves the colon, particularly with left-sided percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL).

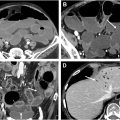

Radiofrequency and microwave ablation can unintentionally cause thermal damage to the bowel near a targeted tumor. In cases involving thermal ablative therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma, bowel injury rates are low (0.11%). Iatrogenic bowel injury from percutaneous cryoablation has also been reported. Imaging findings typically show wall thickening ( Fig. 3 A, B ), focal mucosal disruption, mesenteric stranding, and presence of free fluid or air. Chronic complications like abscesses or fistula formation can occur. Patients with extensive fibrosis, which reduces the distance between the tumor and bowel, and those needing larger treatment zones are at higher risk. In such cases, hydrodissection may be considered to minimize complications.

Percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy (PRG) and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement complications are uncommon, including bowel traversal and intraluminal malposition ( Fig. 4 A–C ), with the colon more commonly traversed compared with the small bowel. Colonic injuries following PEG and PRG have been reported in 0.11% and 0.2% of patients, respectively. Asymptomatic bowel traversal may be more common than expected and early detection before the tract matures has been associated with improved prognosis. Similarly, percutaneous jejunostomy catheter placement can result in complications (including bowel injuries) with a major complication rate of 5%.

In the early postprocedural period, a small amount of pneumoperitoneum is often present on imaging which can make detecting an early bowel injury challenging. A greater than expected or increasing volume of pneumoperitoneum should raise concern for a complication. A more delayed bowel injury from jejunostomy catheters is a pressure ulcer with jejunal perforation ( Fig. 5 ). When a complication is suspected, CT with contrast instilled through the gastrostomy or jejunostomy catheter is recommended to evaluate for wall thickening, pneumoperitoneum, extraluminal contrast, and confirm course and position of the tube.

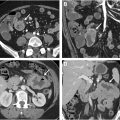

Rates of bowel injury associated with percutaneous biliary decompression techniques are low with bowel injury during percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement reported in 0.56% of patients. The transhepatic approach can help mitigate this risk. Migration of the catheter is the most common reported complication ; however, intraluminal bowel placement can occur ( Fig. 6 A, B ). Biliary stent migration, which can also result in bowel perforation, has an incidence of less than 1%. Perforations primarily happen in the duodenum, and less frequently in the colon. Research indicates that stent migration is more common in benign compared with malignant biliary disease, with plastic biliary stents being more frequently implicated than other types of pancreatic or biliary stents. ,

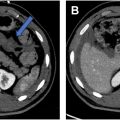

Bowel Injury Associated with Medical Devices

Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD) migration into the bowel ( Fig. 7 A, B ) is an extremely rare event, occurring in approximately 1.2 out of every 1000 insertions. Early detection and removal of the device is important to prevent complications which include obstruction, infarction, fistula formation, mesenteric injury, or perforation. Patients with late perforation may be asymptomatic or present with nonspecific abdominal pain. The sigmoid colon, as reported by Aliukonis and colleagues, is the most frequent site of injury. Ultrasound is the initial imaging choice to confirm the presence or absence of an IUD in the uterus, with CT used to further assess for uterine embedment versus perforation and visceral involvement.

Endoluminal enteric tubes are commonly placed for decompression and feeding and are a simple and safe procedure. Overall complication rates from nasogastric tube placement have been reported to be 0.3% to 15%, including rare duodenal perforation ( Fig. 8 ). Indwelling urinary catheters are commonly used for the management of urinary retention or incontinence, to measure urine output, and to deliver treatment to the urinary bladder. While infection, hemorrhage, and pain are the most common complications of urinary catheter placement, iatrogenic enterovesical fistula ( Fig. 9 A–C ) is a rare complication that has been reported.

Bowel Injury After Endoscopy/Colonoscopy

Upper endoscopic duodenal bowel perforation is uncommon, occurring in less than 0.5% of cases, with incidence increasing with therapeutic intervention. Retroperitoneal gas is present with perforation of the second and third portions of the duodenum ( Fig. 10 A ); with intraperitoneal gas visualized with perforation of the first and fourth portions of the duodenum. Duodenal wall hematoma ( Fig. 10 B) can also be present. Overall endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) complication rates are low and generally increase with intervention. An overall post-ERCP complication rate of 6.85% has been reported with a duodenal perforation rate of 0.08% to 0.6%. On CT, duodenal injuries most commonly manifest as paraduodenal fluid collections but can also show intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal gas and/or extravasation of enteric contrast ( Fig. 11 A–C ). Duodenal perforation from migration of a pancreatobiliary stent (see Fig. 11 ) is a rare complication reported in 0.04% of patients undergoing ERCP with stent placement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree