EROSIVE OSTEOARTHRITIS (EOA)

Erosive osteoarthritis was first described by Kellgren and Moore in 1952 and reintroduced in 1961 by Crain, who called it interphalangeal osteoarthritis. He defined this disorder as a localized variant of osteoarthritis involving the finger joints, characterized by degenerative changes with intermittent inflammatory episodes leading to deformities and ankylosis. In 1966, Peter and Pearson coined the term erosive osteoarthritis, and Ehrlich in 1972 described it as inflammatory osteoarthritis, based on the clinical symptoms of swelling, tenderness, erythema, warmth, and limitation of function. It can be defined as a progressive disorder of the interphalangeal joints with severe synovitis, superimposed on the changes of degenerative joint disease. Although the cause is still unclear, several investigators have suggested hormonal influences, metabolic background, autoimmunity, and heredity as being involved.

Clinical Features

EOA is a progressive inflammatory arthritis seen predominantly in middle-aged women. Only rarely are men affected, with an estimated female-to-male ratio of 12:1. Patients’ ages range from 36 to 83 years, and mean age of onset is 50.5 years. This condition combines certain clinical manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis with certain imaging features of degenerative joint disease. Generally, involvement is limited to the hands, with the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints being the most commonly affected. Large joints, such as the hip or shoulder, are only rarely involved. The arthritis usually begins abruptly and is characterized by pain, swelling, and tenderness of the small joints of the hands. Also described are throbbing paresthesias of the fingertips and morning stiffness.

Pathology

Proliferative synovitis is the most common histopathologic feature of EOA and cannot be distinguished from that of seen in rheumatoid arthritis. Moreover, Peter et al. described findings in some patients consisting of degenerative cartilage with prominent subchondral granulation tissue, lymphocyte aggregates, plasma cell infiltration, and subsynovial fibrosis. Loose fibrin-like material was noted interstitially as well as villous hypertrophy, hyperemia and thickening of the blood vessel walls, and organizing amorphous exudates that overlaid the synovium. Generally speaking, the pathologic synovium of EOA exhibits features that are consistent with both RA and OA.

Imaging Features

In the early stage of the disease, the main feature is symmetric synovitis of the interphalangeal joints. Later, this is followed by articular erosions, which exhibit a characteristic radiographic feature named the “gull-wing” deformity by Martel. This configuration is seen as a result of central erosion and marginal proliferation of bone (

Figs. 6.2 and

6.3); Heberden nodes may also be present. Periosteal reaction taking the form of linear or fluffy bone apposition over the cortex near the affected joints is occasionally

observed. Swelling of soft tissue, usually fusiform, may be present around involved articulations (see

Figs. 6.2A and

6.3E, F); however, periarticular osteoporosis is rarely present. Later in the disease process, bone ankylosis of the phalanges may develop (see

Fig. 6.3G). Approximately 15% of patients with erosive osteoarthritis may have clinical, laboratory, and imaging manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (

Fig. 6.4). The exact relationship between these two conditions is still unclear. Some investigators believe that erosive osteoarthritis is actually rheumatoid arthritis originating in unusual sites but subsequently progressing to the articulations that are more typically involved. Others suggest that each is a distinct entity, citing as evidence the fact that the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis does not resemble that of patients with erosive osteoarthritis, that the immunologic abnormalities commonly seen in rheumatoid arthritis are absent in the latter condition, and that the serologic test for rheumatoid factor is negative.

Because imaging presentation of erosive and nonerosive osteoarthritis may be similar, the investigators were looking into the other means to distinguish these two conditions. The recent studies of serum biomarkers were very promising in this respect. They demonstrated elevation of myeloperoxidase,

C-reactive protein, and serum levels of nitrated form of a marker of type II collagen denaturation (Coll2-1NO2) in patients with EOA.

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS (RA)

Rheumatoid arthritis is a progressive, chronic, systemic inflammatory disease affecting primarily the synovial joints, leading to synovial inflammation and proliferation, loss of articular cartilage, and erosions of subchondral bone. The pathophysiologic hallmark of this condition is formation of pannus, which refers to hypertrophied synovium that develops as inflammatory response. The destructive action of pannus is responsible for progressive erosions and joint surface damage and ligament and joint capsule tearing, all leading to joint deformities and instability. Women are affected three times more often than are men. The course of the disease varies from patient to patient, and there is a striking tendency toward spontaneous remissions and exacerbations.

Although it is much enigmatic, most rheumatologists also include under the rubric of “rheumatoid arthritis” a condition called

seronegative rheumatoid arthritis (see text below), in which patients present without rheumatoid factor or antibodies to CCP but with the clinical and imaging picture of rheumatoid arthritis. Currently, rheumatoid arthritis is considered to be a heterogeneous autoimmune disorder, with genetic factors playing an important role in the disease expression. Multiple genome-wide association studies have been conducted, but the results have generally been disappointing. The genetics is complex and multifactorial and varies between ethnic populations. The best association is with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), but the data have yielded no practical clues that can be translated to the bedside. Although the association with the susceptibility loci of

HLA-DRB1 (which encodes the β-chain of HLA-DR) and

PTPN22 genes is better understood, several non-HLA loci have been linked to this arthritis, including the 18q21 chromosome region of the

TNFRSR11A gene, which encodes the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB. In addition, a common genetic variant at the

TRAF1-C5 locus on chromosome 9 is associated with an increased risk of anti-CCP-positive rheumatoid arthritis. Allelic variants of

HLA-DRB1 associated with risk for rheumatoid arthritis encode a similar sequence, namely, amino acids 70 to 74, known as the shared epitope (SE). The detection of antibodies to citrullinated proteins (CCP), representing specific autoantibodies in the patient’s serum, is an important diagnostic finding.

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology in collaboration with European League Against Rheumatism established new classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Their work “focused on identifying, among patients newly presenting with undifferentiated inflammatory synovitis, factors that best discriminated between those who were and those who were not at high risk for persistent and/or erosive disease—this being the appropriate current paradigm underlying the disease construct ‘rheumatoid arthritis.’” The main advantage of this new classification is focusing on features at earlier stages of rheumatoid arthritis rather than defining the disease by its late-stage features, as it was practiced in the past. In the established new criteria, classification as “definite RA” was based on the presence of synovitis in at least one joint, absence of alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis, and achievement of a total score of 6 or greater (out of possible 10) from the individual scores in four categories: number and site of involved joints (score range from 0 to 5), serologic abnormality (score range from 0 to 3), elevated acute-phase response (score range from 0 to 1), and duration of symptoms (two levels; range from 0 to 1).

Serology of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid factors, so widely used by clinicians, are anti-gamma globulin antibodies that are generally IgM and combine with their antigens (immunoglobulin G [IgG]) to form immune complexes. These complexes activate the complement system, which releases mediators responsible for producing inflammation within the joint structures. Because rheumatoid factors can be found in the serum and in joint fluids of patients with nonrheumatoid disorders, their presence alone is not diagnostic of rheumatoid arthritis. They have been studied for decades and were once thought to be the only critical serologic marker of rheumatoid arthritis; this, however, is not the case, because rheumatoid factors can be found in the joint fluid of patients with nonrheumatoid disorders. Although the rheumatoid factor is still widely used, it has lost much of the luster of the past. Nevertheless, finding high titers of these factors in a joint effusion strongly suggests the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Early in the course of disease, rheumatoid factors may be demonstrated in the synovial fluid before they are positive in the serum, allowing early diagnosis. Rheumatoid factors do participate in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis through the formation of local and circulating antigen-antibody complexes. In synovial fluid, IgM and IgG rheumatoid factors can combine to form immune complexes. The complement system is activated, resulting in the attraction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the joint space. Discharge of their hydrolytic enzymes causes the destruction of joint tissues. The process initiating these events is as yet unknown. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis with subcutaneous nodules almost always will have positive rheumatoid factors, generally in high titer. Interesting, however, is the fact that frequency and severity of rheumatoid nodules has greatly deceased in population and the disease is strikingly different in this respect from two generations ago.

As already discussed in the text above, autoantibodies against the group of citrullinated proteins (CCPs) are more pathognomonic for rheumatoid arthritis than rheumatoid factors. The second-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) tests for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide 2 (anti-CCP2) antibodies have specificity for RA as high as 97%. These antibodies are directed at one or all of the following proteins: alpha enolase, fibrinogen, and vimentin. In all cases, the arginine in these proteins has been replaced by the plant amino acid citrulline. In people with a genetic predisposition to loss of tolerance, autoantibodies to these CCPs appear and may be detected many years before the clinical onset of rheumatoid arthritis. There are several factors known to accelerate this loss of tolerance, including smoking and infections, particularly Proteus infections of the gums.

Clinical Features

Articular and periarticular manifestations include joint swelling and tenderness to palpation, with morning stiffness and severe motion impairment in the affected joints. The clinical presentation varies between the patients, but an insidious onset of pain with symmetrical swelling of the joints of the hands is the most common finding. Some patients may present with palindromic onset, monoarticular presentation, extra-articular synovitis (such as tenosynovitis and bursitis), and general symptoms such as malaise, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and low-grade fever.

Imaging Features

Rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by a diffuse, usually multicompartmental, symmetric narrowing of the joint space associated with marginal or central erosions, periarticular osteoporosis, and periarticular soft tissue swelling; subchondral sclerosis is minimal or absent and formation of osteophytes is lacking.

Large Joint Involvement

Any of the large weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing joints can be affected by rheumatoid arthritis. Regardless of the size of the joint and the site of involvement, certain imaging features can be identified that are characteristic of this inflammatory process.

Osteoporosis

In rheumatoid arthritis, unlike osteoarthritis, osteoporosis is a striking feature. In the early stage of the disease, osteoporosis is localized to periarticular areas (juxta-articular osteoporosis), but with progression of the condition, a generalized osteoporosis can be observed.

Joint Space Narrowing

This is usually a symmetric process with concentric narrowing of the joint. Concentric narrowing in the hip joint leads to axial migration of the femoral head, which in more advanced stages may result in acetabular protrusio (

Figs. 6.5 and

6.6). Similar concentric joint space narrowing is observed in the shoulder joint (

Fig. 6.7). In

addition, cephalad migration of the humeral head may be seen secondary to destructive changes in the shoulder joint and rupture of the rotator cuff (

Fig. 6.8A); resorption of the distal end of the clavicle, which assumes a pencil-like appearance, may also be observed. Tear of the rotator cuff in this condition (

Fig. 6.8B, C) must be differentiated from the chronic traumatic form of this abnormality (

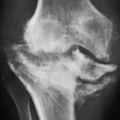

Fig. 6.9). In the knee joint, all three compartments are commonly narrowed in a uniform manner (

Fig. 6.10). The loss of the articular cartilage is caused by inflammation and pannus formation. There is little evidence of bone repair or osteophyte formation, and there is invariably associated joint effusion (

Fig. 6.11). In the elbow and ankle, uniform joint space narrowing is observed (

Figs. 6.12,

6.13,

6.14).

Articular Erosions

Erosive destruction of a joint may be central or peripheral in location. As a rule, reparative processes are absent or very minimal; thus, there is no evidence of subchondral sclerosis or osteophytosis (

Fig. 6.15), which may be present only if secondary degenerative changes are superimposed on the underlying inflammatory process (see

Fig. 5.11).

Osseous Erosions

Loss of the normal radiolucent triangle between the postero-superior margin of the calcaneus and the adjacent Achilles tendon is consistent with the presence of inflammatory fluid within the retrocalcaneal bursa (

Fig. 6.16A), commonly associated with erosion of the calcaneus (

Fig. 6.16B-D). In the hands, the carpal bones are commonly affected (

Figs. 6.17,

6.18,

6.19).

Synovial Cysts and Pseudocysts

These radiolucent defects are usually seen in close proximity to the joint (

Fig. 6.20). They may or may not communicate with the joint space.

Baker Cyst

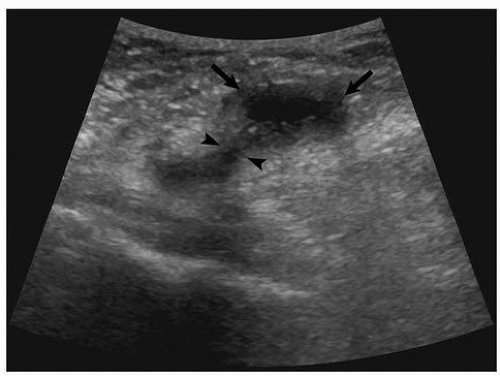

Popliteal cyst is a common finding, seen in ˜48% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and can be detected with ultrasound (

Fig. 6.21, see also

Fig. 2.76A) or with MRI (

Fig. 6.22, see also

Fig. 2.99). It extends posteriorly and may be directed inferiorly or superiorly in the soft tissues in the posterior aspect of the knee joint. Rupture of the Baker cyst leads to extravasation of the inflammatory content into the soft tissues of calf, producing pain and swelling that may be mistaken for thrombophlebitis (see

Fig. 2.77).

Joint Effusion

Fluid can be best demonstrated in the knee joint on the lateral projection (see

Fig. 6.10B). Fluid in the other large joints such as the shoulder, elbow, and hip can be best demonstrated by MRI (see

Figs. 6.13 and

6.16).

Rice Bodies

Bearing macroscopic similarity to grains of polished white rice, these small, usually uniform in size intra-articular

or intrabursal loose bodies are commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis and are thought to represent a complication of chronic inflammatory process. Occasionally, they also may be seen in seronegative inflammatory arthritis and even in tuberculous arthritis. These particles contain collagen, fibrinogen, fibrin, reticulin, elastin, mononuclear cells, blood cells, and some amorphous material (

Fig. 6.23). On radiography (

Fig. 6.24), this condition occasionally can be mistaken for synovial chondromatosis (see

Chapter 10). On MR T1-weighted images, rice bodies exhibit intermediate signal intensity, whereas on T2 weighting, they are only slightly hyperintense relative to muscle (

Figs. 6.25 and

6.26).

Rheumatoid Nodules

They are relatively common, with a reported frequency of ˜25%. They usually develop over pressure areas such as elbow (

Fig. 6.27) or ischial tuberosities.

Small Joint Involvement

Rheumatoid arthritis characteristically affects the small joints of the wrist, as well as the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands and feet. As a rule, the distal interphalangeal joints in the hand are spared, although in advanced stages of the disease even these may be

affected. This latter point, however, is controversial, because some investigators believe that if the distal interphalangeal joints are involved, the condition may represent juvenile idiopathic arthritis or another form of polyarthritis, not classic rheumatoid arthritis.

In addition to the characteristic changes exhibited in large joint involvement, the small joints may also show radiographic features specific for these sites.

Soft Tissue Swelling

This earliest sign of rheumatoid arthritis usually has a fusiform, symmetric shape. It is periarticular in location and represents a combination of joint effusion, edema, and tenosynovitis. Although it can be seen on the radiographs (see

Fig. 6.34), the MRI provides a more effective way of demonstration of this critical feature of pre-erosive rheumatoid arthritis (

Fig. 6.28). MRI also is a modality of choice to show early changes of tenosynovitis (

Fig. 6.29), although ultrasound may effectively demonstrate soft tissue abnormalities at the joints (

Fig. 6.30) as well as tenosynovitis in the hands and feet (

Fig. 6.31, see also

Figs. 2.80 and

2.81).

Loss of Articular Cortex

This is another early radiographic sign of inflammatory arthritis: the so-called articular (or subchondral) cortex becomes indistinct or completely lost (

Fig. 6.32).

Marginal Erosions

Other early radiographic signs of articular abnormalities manifest as marginal erosions at so-called bare areas. These are the sites within the joint capsule that are not covered by articular cartilage (

Fig. 6.33). The most common locations for these erosions are the radial aspects of the second and third metacarpal heads and the radial and ulnar aspects of the bases of the proximal phalanges (

Fig. 6.34). Synovial inflammation in the prestyloid recess, a diverticulum of the radiocarpal joint that is intimate with the styloid process of ulna, as Resnick pointed out, produces marginal erosion of the styloid tip.

Articular Erosions

In more advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis, articular erosions are commonly seen. In the hand, the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are usually affected (

Fig. 6.35) as well as joints of the wrist (

Figs. 6.36 and

6.37, see also

Fig. 6.35A). In the foot, the metatarsophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints are commonly affected (

Figs. 6.38 and

6.39). The subtalar joint may be affected as well (

Fig. 6.40).

Joint Deformities

Although not pathognomonic for rheumatoid arthritis, certain deformations such as the

swan-neck deformity and the

boutonniére deformity are more often seen in this form of arthritis than in other inflammatory arthritides. The first of these represents hyperextension in the proximal interphalangeal joint and flexion in the distal interphalangeal joint, a configuration resembling a swan’s neck (

Fig. 6.41, see also

Fig. 1.3C). In the boutonniére deformity, the configuration is just the opposite, with flexion in the proximal joint and extension in the distal interphalangeal joint (

Fig. 6.42, see also

Fig. 1.3A, B). The word

boutonniére is French for “buttonhole,” the term for this deformity deriving from the configuration of the finger while securing a flower to a lapel. A similar deformation of the thumb is called

hitchhiker’s thumb (see

Fig. 1.2).

Moreover, subluxations and dislocations with malalignment of the fingers are common findings in advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis. Particularly characteristic are ulnar deviation of the fingers in the metacarpophalangeal joints and

radial deviation of the wrist in the radiocarpal articulation (

Fig. 6.43). In far-advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis, shortening of several phalanges may be encountered secondary to destructive changes in the joints associated with dislocations in the metacarpophalangeal joints. This deformity appears as a “telescoping” of the fingers, hence its name,

main en lorgnette, from the French name for the telescoping type of opera glass (

Fig. 6.44). An abnormally wide space between the lunate and the scaphoid may also be encountered in advanced stages of the disease secondary to erosion and rupture of the scapholunate ligament (

Fig. 6.45); this phenomenon is known in the literature as the Terry-Thomas sign. Joint deformities are also often seen in the foot, and subluxation in the metatarsophalangeal joints often leads to deformities such as hallux valgus and hammer toes (

Fig. 6.46).

Joint Ankyloses

A rare finding that may be observed in advanced stages of rheumatoid arthritis is joint ankylosis, which is most commonly encountered in the midcarpal articulations (see

Figs. 6.43 and

6.44). Ankylotic changes in the wrist are more common in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and with so-called seronegative rheumatoid arthritis.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access