Abstract

Lemierre syndrome is a rare and life-threatening condition that typically arises secondary to an oropharyngeal infection, progressing to thrombosis of the internal jugular vein and dissemination of septic emboli, most commonly to the lungs. Diagnosis is confirmed via contrast-enhanced cervicothoracic CT imaging, which identifies the presence of internal jugular vein thrombosis. Immediate treatment involves broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, often utilizing a third-generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactam in combination with metronidazole. In select high-risk cases, anticoagulation may be warranted, and surgical intervention may be indicated in severe presentations. The prognosis hinges critically on the promptness of diagnosis and management, as untreated cases are associated with a significantly elevated mortality risk. We report the case of a 13-year-old girl with no significant medical history, who presented to the emergency department with perioral edema, necrotic lesions with signs of inflammation, right cervical swelling, fever, and progressive deterioration of her general condition in the context of a dental abscess. Clinical, laboratory, and imaging investigations confirmed the diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome. Given the rarity of this condition, maintaining a high level of clinical suspicion is essential to prevent misdiagnosis and delays in initiating appropriate management, which are critical for ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Introduction

Lemierre’s syndrome is a rare but serious condition characterized by septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, bacteremia, and metastatic septic emboli, often secondary to an oropharyngeal infection. The primary pathogen is Fusobacterium necrophorum. Although its incidence decreased after the introduction of antibiotics, a resurgence has been observed due to reduced tonsillectomies and evolving antibiotic stewardship practices [ ].

The clinical course typically involves 2 stages: an initial oropharyngeal infection followed by sepsis and metastatic complications, most commonly affecting the lungs (abscesses and septic emboli). Diagnosis is based on contrast-enhanced cervicothoracic CT imaging and microbiological testing, although culture results may be negative in some cases [ ].

Management includes broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as metronidazole, with anticoagulation reserved for specific cases. Early recognition and treatment are crucial to reducing mortality, which remains approximately 2%-10% with appropriate intervention [ ].

Case presentation

A 13-year-old female patient with no notable medical or surgical history presented to our facility with an oral abscess. The clinical presentation was marked by significant perioral edema and necrotic lesions, accompanied by right cervical swelling that had persisted for 4 days. Additionally, the patient exhibited signs of systemic involvement, including fever, fatigue, and progressive deterioration of her general condition.

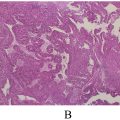

On clinical examination, the patient presented with severe perioral edema accompanied by necrotic black lesions and areas of inflammation characterized by erythema, local warmth, and visible exudates in the submental and perioral regions. The skin also displayed violaceous ecchymoses , suggestive of severe infection or ischemic processes ( Fig. 1 ).

A right-sided cervical swelling , tender on palpation, was noted, raising suspicion of infection spreading to the soft tissues of the neck. Examination of the oral cavity revealed tonsillar hypertrophy , while the lips were swollen and ulcerated .

Laboratory tests were conducted, including a complete blood count, inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and procalcitonin, and microbiological analysis of necrotic tissue samples, which involved bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. Additionally, a PCR panel was performed to detect specific pathogens, including Group A streptococci, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Fusobacterium necrophorum.

The complete blood count revealed lymphocytosis, with a lymphocyte count of 12,500 cells/mm³. Additionally, a significantly elevated C-reactive protein level of 230 mg/L and a procalcitonin level of 2 g/L were noted. Microbiological analysis of the infected tissue samples identified Fusobacterium necrophorum.

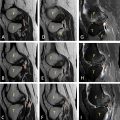

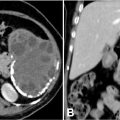

The contrast-enhanced cervical computed tomography revealed the presence of a peritonsillar abscess associated with a mild narrowing of the pharyngeal lumen. The cervical osseous structures and surrounding soft tissues appeared unremarkable, with no significant abnormalities detected ( Fig. 2 ). Additionally, the contrast-enhanced thoracic computed tomography demonstrated a thrombosis of the right internal jugular vein ( Fig. 3 ).

During the multidisciplinary consultation, taking into account the clinical signs, laboratory results, and imaging findings, the diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome was confirmed.

The emergency management strategy involved a combination antibiotic regimen, consisting of a third-generation cephalosporin at a dosage of 50 mg/kg/day and metronidazole at 10 mg/kg, specifically targeting anaerobic pathogens commonly associated with Lemierre’s syndrome, such as Fusobacterium necrophorum. Concurrently, therapeutic anticoagulation was initiated with enoxaparin, a low molecular weight heparin, administered subcutaneously at a dose of 1 mg/kg every 12 h. After 2 months of antibiotic therapy, the clinical course showed remarkable improvement, with follow-up imaging revealing a significant reduction in the size of the tonsillar abscess and substantial improvement in laboratory parameters. By the second month postdiagnosis, the patient’s white blood cell count had normalized, and there was a marked decrease in C-reactive protein levels, indicating resolution of the infection and attenuation of the systemic inflammatory response.

Discussion

The Lemierre syndrome (LS), also known as postanginal sepsis, is a rare but life-threatening condition characterized by internal jugular vein thrombophlebitis, septic emboli, and bacteremia primarily caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. Despite its rarity, LS poses significant risks of morbidity and mortality if not promptly treated. It predominantly affects healthy young individuals, typically between the ages of 15 and 25, with no predisposing medical history. The condition often originates from a pharyngeal infection, and complications may include pulmonary embolism and metastatic infections (musculoskeletal, neurological). Early detection and appropriate antibiotic therapy are essential for improving patient outcomes [ ].

Lemierre syndrome, first described by André Lemierre in 1936, is a rare but serious condition that has seen a slight increase in incidence in recent years. This increase may be associated with reduced empirical antibiotic use for pharyngitis and tonsillitis. A recent Danish epidemiological study reported an annual incidence of 3.6 cases per million people. However, the lack of long-term data makes it difficult to definitively assess trends over time [ ].

Recent studies have indicated that the median age of patients affected by Lemierre syndrome is 23 years, with a higher incidence in males (60%) compared to females (40%) [ ]. Additionally, the majority of cases have been linked to upper respiratory tract infections, such as tonsillitis or pharyngitis, suggesting a significant association between these conditions and the development of Lemierre syndrome [ ].

The disease results from a polymicrobial oropharyngeal infection, most commonly involving Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic commensal of the human upper respiratory tract. The pathogenesis begins with local mucosal injury, followed by bacterial invasion and an inflammatory response, leading to endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis. Dissemination occurs via septic emboli, primarily affecting the lungs, brain, and other organs [ ].

The positive diagnosis of Lemierre’s syndrome is based on clinical, biological, and imaging criteria. The clinical presentation typically begins with oropharyngeal infection accompanied by high-grade fever (≥38.5°C), neck pain, dysphagia, torticollis, and trismus. Physical examination often reveals a painful cervical induration along the sternocleidomastoid muscle, cervical lymphadenopathy, and occasionally signs of a peritonsillar abscess. The medical history frequently includes inadequately treated pharyngitis or tonsillitis [ ]. In advanced cases, systemic signs such as tachycardia, chills, sweating, and hypotension may develop. Additionally, patients may experience pleuritic chest pain, abdominal pain, or joint pain due to secondary septic emboli dissemination [ ].

Paraclinical diagnosis

Imaging : Contrast-enhanced cervicothoracic CT scan is the gold standard examination. It allows for the identification of internal jugular vein thrombosis, appearing as an intraluminal defect with inflammatory wall enhancement. Recent studies highlight its high sensitivity and specificity in detecting septic thrombophlebitis [ ]. In certain cases, it can also help determine the etiology, such as detecting a peritonsillar abscess, and identify complications like pulmonary abscesses or septic emboli [ ]. Cervical Doppler ultrasound can confirm thrombosis and monitor its progression, particularly in resource-limited settings [ ].

Microbiology: The diagnosis is supported by the isolation of Fusobacterium necrophorum in blood cultures or from abscess or blood samples. Advances in molecular diagnostic techniques have improved pathogen detection rates, especially in cases with negative culture results [ ]. In atypical cases, polymerase chain reaction and next-generation sequencing have shown high efficacy in identifying F. necrophorum and associated polymicrobial infections [ ].

Laboratory Findings: A significant elevation in inflammatory markers is commonly observed. Studies indicate that elevated CRP levels >150 mg/L are a strong indicator of disease severity [ ]. Signs of organ dysfunction, such as hypoxemia or renal impairment, are also frequently reported in advanced stages and correlate with worse outcomes [ ].

The differential diagnosis helps exclude various conditions with similar clinical presentations. Infective endocarditis, although associated with septic emboli, is distinguished by the presence of valvular lesions or a cardiac murmur. Chronic pulmonary infections, such as pneumonia or tuberculosis, are not typically linked to internal jugular vein thrombosis. Non-infectious jugular thrombosis may occur in systemic disorders without septic signs. Localized conditions like periamygdaloid abscesses or isolated cervical cellulitis generally do not cause systemic septic dissemination. Lastly, polymicrobial septicemia can lead to septic emboli without specifically involving the internal jugular vein [ ].

The treatment of this condition relies on a multidisciplinary approach, encompassing antibiotic therapy, management of thrombotic complications, and, in selected cases, surgical interventions.

Antibiotic Therapy Antibiotics are the cornerstone of treatment. Current guidelines recommend therapies targeting Fusobacterium necrophorum, the pathogen most commonly implicated in Lemierre’s Syndrome :

- •

Metronidazole, often employed as a first-line agent, either alone or combined with a beta-lactam such as penicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate [ ].

- •

Clindamycin, especially in patients with contraindications to beta-lactams.

- •

Carbapenems, reserved for severe cases or co-infections involving resistant organisms [ ].

Recent evidence confirms high susceptibility of F. necrophorum to these agents, although sporadic resistance to erythromycin has been observed [ ]. Prolonged antibiotic therapy, typically 4 to 6 weeks, is necessary to achieve complete eradication of the infection and to prevent recurrence.

The use of anticoagulants in the management of Lemierre syndrome remains controversial. Recent meta-analyses have not demonstrated a significant impact on thrombus recanalization or mortality. However, specific clinical scenarios may warrant their use, such as:

- •

Significant thrombus extension into critical structures.

- •

High risk of septic emboli migration.

- •

Inadequate response to antibiotic therapy alone [ ].

Low-molecular-weight heparins are commonly employed, whereas the use of direct oral anticoagulants remains limited. Decisions regarding anticoagulation should be individualized, carefully balancing the potential benefits against the associated hemorrhagic risks [ ].

Surgical procedures may be required to drain cervical or pulmonary abscesses and to excise or ligate thrombosed jugular veins in cases where conservative treatments fail [ ]. Early identification of metastatic abscesses through imaging modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging is critical for effective management planning.

With advancements in antibiotic therapy and earlier diagnosis, the mortality associated with Lemierre syndrome has decreased to below 5% [ ]. However, severe complications, particularly pulmonary and neurological, persist in approximately 30% of hospitalized patients. Optimal management, including early and targeted antibiotic treatment, significantly improves clinical outcomes [ ].

Conclusion

Lemierre syndrome is a rare but potentially fatal condition characterized by thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, septic emboli, and bacteremia, typically caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. It predominantly affects healthy young individuals, often following an upper respiratory tract infection like pharyngitis or tonsillitis. Early detection is critical, as delays in treatment can result in severe complications, including pulmonary embolism, neurological infections, and systemic sepsis. Diagnosis relies on clinical, microbiological, and imaging criteria, with contrast-enhanced CT scans being the gold standard. Antibiotic therapy targeting F. necrophorum, often using metronidazole or clindamycin, is central to treatment, with a prolonged course required for complete infection eradication. Although anticoagulant use remains debated, they may be beneficial in certain cases with extensive thrombus or high embolic risk. Despite advancements in antibiotic therapy, the condition still carries a significant risk of severe complications and requires a multidisciplinary approach for optimal management. Early intervention has reduced mortality rates to below 5%, but approximately 30% of patients experience persistent pulmonary or neurological sequelae.

Patient consent

The patient has provided informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments: We extend our gratitude to the otorhinolaryngology department team at the university hospital for their management and availability. This study did not receive any specific funding from public, commercial, or nonprofit funding agencies.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree