Management

Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH)

Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH)

Columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions (CAPSS)

Complex sclerosing lesion

Cribriform ductal carcinoma in situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Ductography

E-cadherin

False negative (FN)

False positive (FP)

Fibroadenoma

Hyperplasia

Incident cancer detection rate

Intracystic carcinoma

Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR)

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)

Lobular neoplasia

Local recurrence

Medical audit

Micropapillary ductal carcinoma in situ

Minimal breast cancer

Mucocele-like lesion

Multiple peripheral papillomas

Papilloma

Papillomatosis

Phyllodes tumor

Pneumocystogram

Positive predictive value (PPV)

Prevalent cancer detection rate

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH)

Radial scar

Regional recurrence

Sclerosing adenosis

Secretory carcinoma

Sensitivity

Specificity

True negative (TN)

True positive (TP)

In managing the various situations that arise in breast imaging, it is good to always be thinking not just relative to what the first step should be for your patient’s care, but what the second and third steps might be as well. Your patient? Yes, your patient. Know and consider the cascade of events you precipitate for patients based on what you say to them, how you word your report, and the recommendations you make. Are you sure enough about what you are saying to justify whatever ensues for the patient? Is your decision motivated by a defensive posture and the recognition, at some level, that the workup is incomplete (substandard) and that you are operating with inadequate or incomplete information, or one that is justifiably based on common sense, a complete workup, and what is good for the patient?

The need for correlation in every process undertaken is fundamentally important. If an ultrasound is done to evaluate a mammographic or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) finding, does what you see on ultrasound correlate with the mammographic or MRI finding? If the patient presents with a focal finding, does what you see mammographically correlate with the described clinical finding? When recommending an imaging-guided or excisional biopsy, consider what you will accept as a diagnosis and what you will recommend if the results are different from those expected. Are the imaging and histologic findings concordant? If the imaging and histologic findings are benign and congruent, patients can be returned to annual screening mammography. For patients diagnosed with a malignancy, MRI and surgical consultation are scheduled. If the findings are not concordant, repeat biopsy or excisional biopsy is recommended. For patients with a diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), possible phyllodes tumor, multiple peripheral papillomas, fibromatosis, or granular cell tumor, wide surgical excision is indicated following imaging-guided biopsies.

The management of several types of lesions diagnosed on core biopsies remains controversial. Included in this group are solitary papillomas, lobular neoplasia (atypical lobular neoplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ), complex sclerosing lesions, and mucocele-like

lesions. The current consensus is that excisional biopsy is appropriate when these lesions are diagnosed on core biopsies because of the reported incidence of associated malignancy and the frequency with which some of these lesions are upgraded to cancer when more tissue is examined histologically.

lesions. The current consensus is that excisional biopsy is appropriate when these lesions are diagnosed on core biopsies because of the reported incidence of associated malignancy and the frequency with which some of these lesions are upgraded to cancer when more tissue is examined histologically.

As mentioned previously, regardless of the type of study done, the title on the written description of what I do is worded as a “Breast Imaging Consultation” not a “Radiology Report.” The comprehensive evaluations that can be undertaken by breast imagers have put us in a consultative role. A general outline used for breast imaging consultative reports includes:

Type of study (e.g., screening or diagnostic mammogram, ultrasound)

Succinct description and location of findings

Impression, with your specific recommendations

Assessment category (required under the Mammography Quality Standards Act for all mammographic studies) with wording as provided by the American College of Radiology, Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS®) for mammography:

Category 1: negative

Category 2: benign finding

Category 3: probably benign finding; short-interval follow-up is recommended

Category 4: suspicious abnormality—biopsy should be considered

Category 5: highly suggestive of malignancy—appropriate action should be taken

Category 6: known biopsy-proven malignancy—appropriate action should be taken

Category 0: need additional imaging evaluation and/or prior mammograms for comparison

Category 4 lesions can be further subdivided at the discretion of the facility for their internal use into:

Category 4A: low suspicion for malignancy

Category 4B: intermediate suspicion for malignancy

Category 4C: moderate concern

I make every effort to generate descriptive but succinct reports that are clinically relevant and that provide specific direction and recommendations. I use no disclaimers in my reports, and I do not abdicate clinical correlation of anything to others. In considering the wording of reports, it is my contention that if, based on complete clinical and imaging evaluations, you have a high degree of certainty relative to the diagnosis, clear consultative reports with specific recommendations can be dictated easily and succinctly (e.g., “a spiculated mass measuring 7 mm is imaged at the 3 o’clock position, 5 cm from the right nipple. Biopsy is indicated. This is undertaken and reported separately.”). Make up your mind about what you are going to say before you start dictating. Hedges and disclaimers are used when we are uncomfortable and uncertain about a finding and its significance. In this situation, I would suggest that we need to do whatever it takes to increase our level of certainty so that we can be more definitive.

For potentially abnormal screening mammograms, I state what the potential abnormality is (e.g., mass, calcifications, distortion) and in which breast it is located; I also comment specifically on the other breast. The description and characterization of the lesion is deferred until a thorough evaluation is completed (e.g., for a mass, spot compression views, physical examination, and an ultrasound). The recommendation for a woman with a potentially abnormal screening mammogram is “additional evaluation is indicated and we will contact the patient directly to schedule the additional evaluation” (see the introduction to Chapter 2 for additional discussion). Consequently, the only assessment categories used for screening mammograms are 0, 1, and 2.

In the diagnostic setting, I issue one consultative report that includes the findings for the diagnostic mammogram, physical examination, and ultrasound. Based on the clinical and imaging features of a lesion, the findings are described and an impression with recommendations is generated. The impression is not used to repeat a description of the findings but rather is used to deliver the final, clinically relevant concept with what I think is indicated for the patient.

Read your reports critically. Strive for precision (e.g., give measurements for a lesion and avoid characterizations such as “small” or “large”) and eliminate unnecessary words (e.g., “clearly,” “appears to be,” “very,” etc.) that provide no relevant information and may serve to obscure your message. It is important to familiarize yourself with the mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging lexicons provided by the American College of Radiology, Breast Imaging and Reporting Data System (BI-RADS®), as these provide guidelines on what should be described for particular findings and suggests terminology to be used for relevant findings.

In breast imaging, accountability needs to be present every step of the way. Although quality control and data tracking are often relegated to the technologist, radiologists should be actively involved in these processes for their practice. It is only through monitoring results that problems can be addressed and much learning can take place. We need to know how well we are doing, and we want to identify potential problems that can be addressed so that patient care is improved. By tracking data and learning from the results, we can improve patient care. The numbers generated from the audit should be viewed not as one point in time but rather how they change as you gain more experience.

Data that should be collected include:

Date of audit

Number of screening studies (first-time study vs. repeat screen)

Number of diagnostic studies

Call-back (recall) recommendations (e.g., BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation)

Biopsy recommendations (BI-RADS® category 4 and 5: suspicious abnormality and highly suggestive of malignancy)

Biopsy results (e.g., benign vs. malignant; FNA vs. core biopsy vs. excisional biopsy)

Tumor staging: histologic subtype, grade, size, and nodal status

Data that you can calculate include:

True positive (TP): cancer diagnosed within 1 year of a biopsy recommendation for an abnormal mammogram

True negative (TN): no known cancer within 1 year of a normal mammogram

False negative (FN): cancer diagnosed within 1 year of a normal mammogram; these should be reviewed and analyzed

False positive (FP):

FP1 = no known cancer diagnosed within 1 year of an abnormal screening mammogram for which additional imaging or biopsy is recommended

FP2 = no known cancer diagnosed within 1 year of a recommendation for biopsy or surgical consultation based on an abnormal mammogram

FP3 = benign disease diagnosed on biopsy within 1 year after recommendation for biopsy or surgical consultation based on an abnormal mammogram

Positive predictive value:

PPV1 = percentage of cancers diagnosed following an abnormal screening mammogram

PPV2 = percentage of cancers diagnosed when a biopsy or surgical consultation is recommended following a screening mammogram

PPV3 = percentage of cancers diagnosed on the actual number of biopsies done as a result of a screening mammogram

Cancer detection rate for asymptomatic women (i.e., true screening population)

Prevalent (rate of cancer detection among women presenting for their first screening mammogram)

Incident (rate of cancer detection among women with prior screening mammograms)

By age groups

Percentage of minimal breast cancers diagnosed

Percentage of node-negative breast cancers diagnosed

Call-back (recall) rate

Sensitivity =TP/(TP + FN), or the probability of detecting a cancer when a cancer is present

Specificity =TN/(FP + TN), or the probability of a normal mammogram when no cancer is present

Based on reports of audit data, obtainable goals include:

PPV1 (abnormal screens): 5% to 10%

PPV2 (biopsy recommendations): 25% to 40%

Stage 0 or 1 tumors diagnosed: > 50%

Minimal cancers (invasive cancer ≥ 1 cm or DCIS): > 30%

Node-positive tumors: < 25%

Prevalent cancers/1,000: 6 to 10

Incident cancers/1,000: 2 to 4

Call-back (recall) rate: ≥10%

Sensitivity: > 85%

Specificity: > 90%

Published sensitivity rates for mammography range between 85% and 90%. Recognize, however, that this is probably one of the harder statistics to obtain because of the difficulty of establishing an accurate false negative rate. Access to a statewide tumor registry can be helpful; however, if the patient moves (or seeks medical care) out of state, knowledge of a cancer diagnosis may not be readily accessible to the screening facility.

The effect of breast imaging and the role of radiologists in the management of women with breast cancer goes unstated and, in many ways, is often misrepresented. There is continued skepticism and criticisms relative to our contributions to patient care and the significance of what has already been accomplished: the routine identification of lymph node-negative stage 0 and stage I invasive cancers and ductal carcinoma in situ. Recently reported decreases in breast cancer mortality rates are attributed by many to more effective treatment, ignoring or relegating to a secondary role our ability to detect DCIS, stage 0, and stage I lesions in many patients. Is early detection possibly the more important factor, and does not our ability to identify small lesions increase available treatment options and render them more effective for patients?

Patient 1

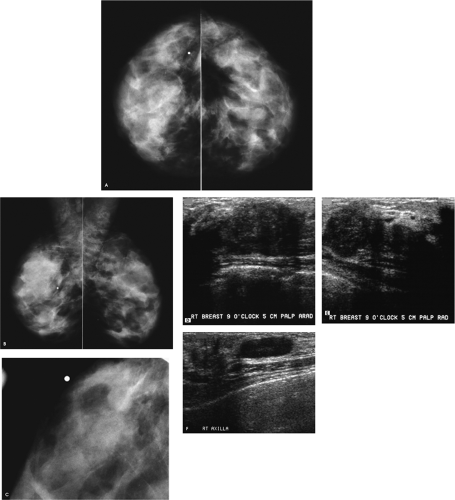

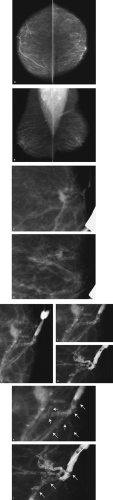

Figure 4.1. Screening study, 60-year-old woman. Craniocaudal (A) and mediolateral oblique (B) views, right breast. Craniocaudal (C) and mediolateral oblique (D) spot compression views, right breast. |

What do you think?

What would you do next?

A mass with a radiolucent center, associated distortion, and long spicules is present anteriorly in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. Given these features, fat necrosis related to a prior biopsy is one of the main considerations. As a starting point, prior films would be helpful in determining if this finding could be seen previously, and what, if any, evolution has occurred. A review of the patient’s history form, looking specifically to see if she has had a biopsy at this site, will also be helpful. Unfortunately, no prior films are available for this patient, and nothing is indicated on the history form relative to a prior biopsy in the right breast. Additional evaluation is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation.

The spot compression views confirm the presence of a mass with a low-density central area, distortion, and long spiculation. The differential for this finding includes fat necrosis related to prior surgery or trauma, complex sclerosing lesion, sclerosing adenosis, papilloma, focal fibrosis, an inflammatory process, invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, tubular carcinoma, and invasive lobular carcinoma. In discussing the findings with the technologist, she relates not seeing a scar at the site of the spot views. Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated next.

After introducing myself to the patient and briefly describing what we have seen so far and what I would like to do next, I specifically ask her about prior breast surgery or trauma. She has no recollection of having had surgery or trauma to the right breast. On close inspection of the periareolar region, however, a scar is apparent at the edge of the areola corresponding to the site of the mammographic finding. I palpate no corresponding mass, elicit no tenderness at this site, and the ultrasound is normal throughout the subareolar area extending into the upper outer quadrant of the right breast.

As I approached the patient, I remained open to all diagnostic possibilities; however, I had some skepticism relative to the information provided. In my mind, the mammographic findings (low

central density, distortion, and long spiculation), in the absence of a palpable finding, were highly suggestive of fat necrosis or a complex sclerosing lesion. So, rather than totally discard my initial impression, I examine the patient carefully, focusing my attention on the site of the mammographic findings. Although the patient has no recollection of prior surgery (patients do not always recall prior surgical procedures, trauma, or inflammatory processes; some may not even recall a breast cancer diagnosis), and the technologist reported no scars, by spending 2 minutes closely examining the patient, the diagnosis of postoperative change is established and no additional intervention or follow-up is recommended.

central density, distortion, and long spiculation), in the absence of a palpable finding, were highly suggestive of fat necrosis or a complex sclerosing lesion. So, rather than totally discard my initial impression, I examine the patient carefully, focusing my attention on the site of the mammographic findings. Although the patient has no recollection of prior surgery (patients do not always recall prior surgical procedures, trauma, or inflammatory processes; some may not even recall a breast cancer diagnosis), and the technologist reported no scars, by spending 2 minutes closely examining the patient, the diagnosis of postoperative change is established and no additional intervention or follow-up is recommended.

Given our total fascination with technology and images, we often dismiss or underestimate simple and inexpensive tools such as physical examination, and yet this often provides the correct answer expeditiously. I cannot emphasize enough how many times direct communication with the patient and a thorough physical examination provide an efficient means of arriving at the correct answer for a given patient. As clinical breast imagers, we are in a unique position to integrate clinical, physical, imaging, and histologic findings to provide accurate, optimal patient care. Do not sell yourself or your patients short by passing up an opportunity to examine and talk to the patient directly. Do not relegate physical examination and the performance of ultrasound studies to others.

Patient 2

What do you think?

What would you do next?

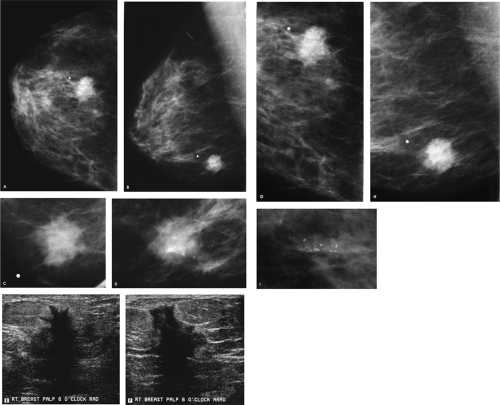

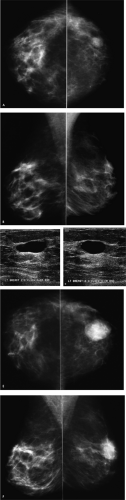

There is dense fibroglandular tissue, and no focal abnormality is apparent on the spot tangential view. Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated for further evaluation.

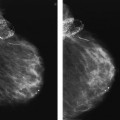

On physical examination, a hard, fixed mass is palpated at the 9 o’clock position, 5 cm from the right nipple. On ultrasound, (Fig. 4.2D, E), an irregular mass with a heterogeneous echotexture, indistinct margins, and areas of shadowing and enhancement is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. This mass measures at least 5 cm. The clinical and sonographic findings are consistent with a malignant process, most likely an invasive ductal carcinoma. A biopsy is indicated.

What else should you do to evaluate this patient further?

For patients in whom we suspect a malignancy, we examine the ipsilateral axilla for potentially abnormal lymph nodes. If any potential abnormality is identified in the axilla, a fine-needle aspiration or a needle biopsy is also done. Patients with metastatic disease to the axilla will undergo a full axillary dissection at the time of the lumpectomy, bypassing the need for a sentinel lymph node biopsy.

In this patient, an oval hypoechoic mass is imaged in the right axilla (Fig. 4.2F). Given the thickening of the cortex and the lack of a hyperechogenic hilar region, this is a potentially abnormal lymph node. Biopsies of the right breast and axillary masses confirm the suspected diagnoses. At the time of her definitive surgery, a grade III invasive ductal carcinoma with extensive lymphovascular space involvement measuring at least 5.7 cm in size is reported histologically. Tumor is also reported in the dermal lymphatics surrounding the right nipple [pT3, pN2, pMX; Stage IIIA].

In patients with palpable findings and normal-appearing dense glandular tissue mammographically, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated for further evaluation. In this group of patients, ultrasound is an excellent adjunctive tool in evaluating the clinical findings. If our focus is optimal, efficient, and expeditious patient care, then clinical, mammographic, and sonographic evaluations and, when needed, imaging-guided biopsies of the breast and axilla, are done in one visit. With a 24-hour turnaround time on core biopsy results, histology findings are available the following day and the patient is scheduled to see the surgeon for definitive treatment. As clinical breast imagers, we are in a unique position to affect the care our patients receive. Evaluations, which in many communities take weeks, with significant associated anxiety for the patient and her family, can be accomplished accurately in 24 hours. By providing this type of service, we also effectively eliminate the fragmentation of care (and with that the potential for miscommunication) among providers that can result when evaluations are carried out over several weeks (e.g., one radiologist doing the initial mammogram, another doing the ultrasound, and possibly a third doing the biopsies).

Patient 3

What do you think?

A round, solid, 2-cm mass with spiculated, indistinct, and angular margins and associated shadowing is imaged in the right breast, corresponding to the area of concern to the patient. Although no calcifications are identified associated with the mass on the craniocaudal spot compression view, or on the ultrasound, a cluster of pleomorphic calcifications is evident on the mediolateral oblique spot compression view. Why are these not seen on the spot craniocaudal view? Did you see them on the routine craniocaudal view, or was your eye drawn to the clinical finding? Remember, do not let yourself be distracted by obvious benign or malignant mammographic/clinical findings. Even when you are presented with an obvious finding, make sure to evaluate the remainder of the mammogram and the contralateral side thoroughly.

What do you think now?

What is your recommendation?

The calcifications project on the mass in the mediolateral oblique view, but they are medial in location on the craniocaudal view and at a distance from the mass. On the magnification views, the calcifications are pleomorphic and there are associated linear forms consistent with ductal carcinoma in situ with central necrosis, likely high-nuclear-grade. Biopsies of the mass and calcifications are indicated because if these confirm the suspected diagnoses, this represents multicentric disease and a mastectomy is probably indicated for this patient.

Histologically, a complex ductal carcinoma in situ is diagnosed, corresponding to the cluster of calcifications seen mammographically, and a 2.5-cm, grade III, invasive ductal carcinoma with associated lymphovascular space involvement is described for the mass. Micrometastatic disease is reported in the sentinel lymph node [pT2, pN1mi(sn) (i), pMX, Stage IIB].

Given the incidence of multifocal, multicentric, and bilateral lesions, thorough evaluation of patients who are likely to have

a malignancy is critical preoperatively. The mammogram needs to be reviewed carefully. Complete ultrasound evaluations of the breasts and ipsilateral axilla, as well as magnetic resonance imaging, are also helpful in evaluating patients diagnosed with breast cancer. With appropriate imaging protocols, magnetic resonance imaging also makes the evaluation of internal mammary, axillary, supraclavicular, and neck lymph nodes possible for our patients.

a malignancy is critical preoperatively. The mammogram needs to be reviewed carefully. Complete ultrasound evaluations of the breasts and ipsilateral axilla, as well as magnetic resonance imaging, are also helpful in evaluating patients diagnosed with breast cancer. With appropriate imaging protocols, magnetic resonance imaging also makes the evaluation of internal mammary, axillary, supraclavicular, and neck lymph nodes possible for our patients.

Patient 4

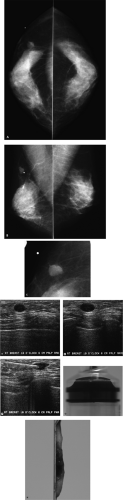

What do you think?

Is this a normal study, or is there a potential abnormality?

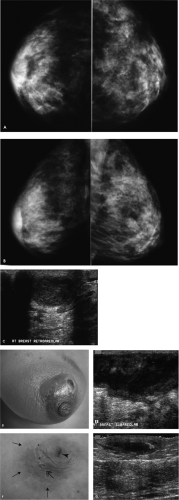

A lucent-centered, benign-type calcification is present in the right breast medially. In reviewing these images systematically, a potential abnormality is noted medially in the left craniocaudal (CC) view. Based on the expected location of this abnormality on the CC view, a low-density nodule is suspected inferiorly on the left mediolateral oblique view. If they are available, prior films would be helpful in assessing whether this finding is new, stable, or decreasing in size. If prior films are not available or this represents a new or enlarging mass, additional evaluation is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation.

What do you think now, and with what level of certainty can you make a recommendation?

Did you notice the fingerprint superimposed on the mass in the craniocaudal spot compression view? This is a plus-density artifact that reflects improper film handling after the film was exposed but before processing. An oval mass with indistinct and spiculated margins is confirmed on the spot compression views. Based on the mammographic findings, this mass requires biopsy. In planning the biopsy, an ultrasound is done because, if the lesion is identified on ultrasound, ultrasound guidance can be used to do the biopsy. If the mass is not identified sonographically, a stereotactically guided biopsy can be done.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

Based on the mammographic and sonographic findings, what will you accept as a diagnosis for this mass?

A hypoechoic mass is imaged at the eight o’clock position, 4 cm from the left nipple. Using ultrasound guidance, a biopsy of this mass is done. Fibrocystic changes are reported histologically. What do you think? What would you recommend for this patient? The imaging and pathology findings are not congruent. Given the mammographic features of this mass, the likelihood of malignancy is high and a benign diagnosis on the cores is not acceptable.

In assessing this situation and problem solving in general, it is helpful to go back to basics. The pathologist should be asked if additional sectioning of the cores can be done, because sometimes the lesion is deep in the cores and it is possible that the lesion has not yet been examined histologically. If all available tissue has been sectioned and examined, the mammographic and ultrasound images should be reviewed. Do the images obtained during the biopsy confirm adequate positioning of the needle through the mass? Ideally, orthogonal images of the needle are obtained during the biopsy to document final needle positioning. With small lesions it is particularly important to document that the needle is associated with the mass longitudinally as well as in cross section (Fig. 4.4F [I and III] and Fig. 4.4G, I). There are times when the needle appears to be through the mass longitudinally, but the needle is actually just at the edge of the mass (and not in it) when the needle is imaged in cross section (Fig. 4.4F [II] and Fig. 4.4H). Lastly, you have to ask yourself: Does what is seen sonographically correlate with the mammographic finding?

In this patient, the pathologist has reviewed all available material and the images during the biopsy document adequate needle positioning. What do you think relative to the correlation of the lesion seen mammographically with what is imaged on ultrasound? At what clock position would you expect to find the mammographic finding, and at what distance should this lesion be from the nipple? The lesion is expected at the 8 o’clock position; however, in measuring back from the nipple, this lesion is closer to 8 cm and not 4 cm (Fig. 4.4J–L) from the nipple. When the patient is scanned at the 8 o’clock position, 8 cm from the nipple, a 9-mm spiculated mass with angular margins and associated shadowing is imaged at this site (Fig. 4.4M, N). This corresponds with the mass seen mammographically and its ultrasound features suggesting a malignant process correlate closely with those seen mammographically. Ultrasound guidance is used preoperatively to localize the mass at the 8 o’clock position, 8 cm from the left nipple (Fig. 4.4O). A 0.8-cm, well-differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified is reported following the lumpectomy. No metastatic disease is identified in two excised sentinel lymph nodes [pT1b, pN0, pMX; Stage I].

Correlation is critically important. For clinical findings, does what is seen mammographically correlate with what the patient or the clinician is describing? In this situation, talking directly to the patient while doing a physical examination and the ultrasound study can provide the needed correlation. Specifically, ask the patient to show you the location of what she is feeling. For mammographic findings, is what is seen on the ultrasound the same thing as what is on the mammogram? If I am doing an ultrasound for a mammographic finding, I walk into the ultrasound room with an expected clock position in mind and an estimated distance from the nipple. This is my starting point for the physical examination and where I place the transducer. After I have evaluated this area fully, I scan the remainder of the quadrant or the breast as needed. For findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is what is seen on the ultrasound the same thing as what is on the MRI? Knowing slice thickness, the distance of the lesion with respect to the nipple can be estimated and used as the starting point for the ultrasound study. If an imaging-guided biopsy is done, are the imaging and histologic findings congruent? If they are not congruent, is the problem with the imaging or is there a possibility the lesion has not been evaluated histologically (i.e., has all tissue been sectioned?)?

Lastly, following excisional biopsies, is there correlation between clinical and imaging findings and the reported histology? Specimen radiography is used to confirm that a clinically occult, preoperatively (wire) localized lesion is excised and the location of the lesion in the specimen is marked for the pathologist, thereby assuring that the lesion is examined. However, for patients in whom preoperative localization and specimen radiography are not done, we have had situations in which a solid, water-density mass is reportedly excised based on palpable findings and a lipoma or other noncongruent lesion is reported histologically. In this situation either the lesion was not excised or the pathologist did not evaluate the lesion of interest in the specimen. In these patients, repeating the mammogram is helpful in determining whether the lesion of interest has been excised.

If we are methodical in our approach and provide the needed correlation at every step of the process, the clinical breast imager is a critical factor in optimizing patient care. We are in a unique position to provide the needed correlation among clinical, imaging, and histologic findings.

Patient 5

What are your observations?

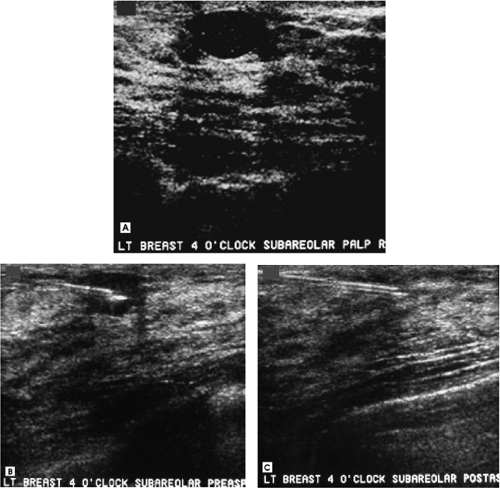

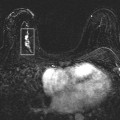

There is increased density in the right subareolar area corresponding to the site of concern to the patient. In looking at the technical factors, the right breast is less compressible and a higher kilovoltage and milliamperage were needed for exposure when compared with the left breast. Physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated for further evaluation.

On physical examination, erythema and peau d’orange changes are noted in the periareolar area. Significant tenderness is elicited with gentle compression. A mass is palpated in the right subareolar area. Sonographically, a mass with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged in the subareolar area, corresponding to the palpable finding (Fig. 4.5C). Based on the clinical presentation and the imaging findings, an ongoing inflammatory process is suspected. The patient is started on antibiotics.

The patient returns within 72 hours, describing progressive symptoms and purulent fluid draining from the periareolar area. On physical examination, erythema and peau d’orange changes are again noted, but these are now much more extensive and there is now a protuberant mass extending into the upper inner quadrant of the right breast. The overlying skin is thinned and there is a fistula draining purulent fluid at the areolar margin at the 1 o’clock position (Fig. 4.5D). On ultrasound, the abscess has increased in size (Fig. 4.5E). Given the rapid progression of symptoms, the formation of a fistula, and the subareolar location of this abscess, the patient is transferred to the hospital for consultation and surgical drainage.

When considering mastitis and abscess formation, what groups of patients should you consider?

Three different patient populations can be considered relative to mastitis and breast abscess formation. Most commonly, we associate these inflammatory conditions with women who are breastfeeding: This is puerperal mastitis. Reportedly, mastitis occurs in approximately 2.5% of women who breastfeed, and abscess formation affects >,1 in 15 of all women who breastfeed. In this patient population, Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative agent. Patients with mastitis alone are usually treated effectively with antibiotics. If an abscess develops, percutaneous drainage can be helpful, and surgical drainage may be required for some patients. These patients are usually treated by their obstetricians and are not usually referred for imaging.

The second group of patients to consider in terms of breast infections is those with recurring subareolar abscess formation unrelated to nipple piercing or nipple rings. These patients are nonlactating, premenopausal women, most with a history of heavy smoking. As seen in this patient, many of these patients develop periareolar fistulas spontaneously (Zuska’s disease). Squamous metaplasia involving the subareolar ducts is seen histologically in these patients, and it is postulated that this process leads to obstruction of the ducts, with inspissation of secretions, duct wall erosion, and the development of periductal mastitis and abscess formation. Antibiotic therapy alone is not usually effective in these patients. Although some have advocated percutaneous drainage, this also is not always effective, and wide surgical excision is required. Even in the patients who undergo surgical drainage, however, there is a high incidence of recurrence. With recurrent episodes, the nipple begins to flatten and some patients develop horizontal inversion centrally in the nipple (Fig. 4.5F, G). Bilateral abscess formation is seen in as many as a quarter of these patients, either simultaneously or at different times. A mixture of aerobic and anaerobic organisms is often cultured in these patients. It has been reported that these patients have a higher incidence of acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, and perineal inclusion cysts.

Lastly, peripheral mastitis or abscess formation can be seen unrelated to pregnancy and lactation. Rarely, some of these patients are diabetic; most of the women in this group, however, are otherwise healthy, with no identifiable source of infection. These patients respond well to antibiotic therapy and infection usually does not recur. They are also unlikely to present with bilateral findings.

Patient 6

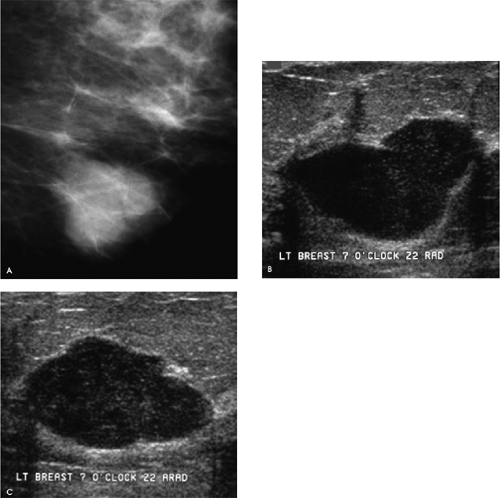

How would you describe the imaging findings?

A 2-cm, macrolobulated mass, with partially well circumscribed and indistinct margins, is seen mammographically. On ultrasound, a well-circumscribed, irregular mass with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged at the 7 o’clock position, zone 2 (Z2), corresponding to the mammographic finding. Although a cyst is suspected, the presence of internal echoes and the irregular shape of this mass are such that this cannot be called a simple cyst. A cyst aspiration is undertaken. In discussing this with the patient, I tell her that if I do not obtain fluid, or if there is a residual abnormality postaspiration, I will do a needle biopsy and obtain tissue for histologic evaluation.

After establishing an approach that allows me to advance the needle parallel to the transducer, I clean the skin and use lidocaine to anesthetize the skin. Then, using ultrasound guidance, I inject lidocaine into the tissue leading up to, but taking care to not go into, the lesion. I use ultrasound guidance for administering the anesthesia and for doing the aspiration, even in those patients in whom the mass is palpable. Commonly, the advancing needle displaces the mass, or indents the wall, but does not penetrate into the mass

(I think this explains many of the patients who present for evaluation of a palpable mass following attempted aspirations that yielded no fluid and yet we find a cyst corresponding to the palpable finding). By visualizing the trajectory of the advancing needle, I can gauge the amount of compression I need to apply to effectively immobilize the mass and the amount of controlled pressure I need to exert with the needle so that the cyst wall is punctured. Once the needle is in the mass, I pull the stylet out of the 20G spinal needle, attach a 10-mL syringe, and aspirate. I watch on real-time ultrasound as I aspirate to be sure there is no residual abnormality postaspiration. Also, in some patients, the needle may need to be redirected (i.e., the tip of the needle put against the cyst wall) during the aspiration to be sure that all of the fluid is aspirated. If I do not obtain fluid, I may try using an 18G spinal needle, and if I still do not obtain fluid, or if there is a residual abnormality postaspiration, I proceed with core biopsies using the 14G needle.

(I think this explains many of the patients who present for evaluation of a palpable mass following attempted aspirations that yielded no fluid and yet we find a cyst corresponding to the palpable finding). By visualizing the trajectory of the advancing needle, I can gauge the amount of compression I need to apply to effectively immobilize the mass and the amount of controlled pressure I need to exert with the needle so that the cyst wall is punctured. Once the needle is in the mass, I pull the stylet out of the 20G spinal needle, attach a 10-mL syringe, and aspirate. I watch on real-time ultrasound as I aspirate to be sure there is no residual abnormality postaspiration. Also, in some patients, the needle may need to be redirected (i.e., the tip of the needle put against the cyst wall) during the aspiration to be sure that all of the fluid is aspirated. If I do not obtain fluid, I may try using an 18G spinal needle, and if I still do not obtain fluid, or if there is a residual abnormality postaspiration, I proceed with core biopsies using the 14G needle.

In this patient, 8 mL of greenish fluid is aspirated and no residual abnormality is seen following the aspiration. At this point, I inject 4 mL of air (50% of the aspirated fluid volume) into the cyst cavity, because it has been suggested that by doing this we can lower the incidence of cyst recurrence. The air does not hurt the patient, and if it is helpful in minimizing the likelihood of a recurrence, it can be beneficial to the patient. If I am concerned about the presence of a mural or intracystic abnormality, spot compression magnification views of the mass are done following the injection of air in the cyst (i.e., a pneumocystogram) to further evaluate the wall of the cyst.

As a routine, I discard aspirated fluid. Intracystic carcinomas are rare (0.5% of all carcinomas and >,0.1% of cysts), and even when an intracystic carcinoma is present, negative cytology is obtained in more than half of patients. I submit fluid for cytology if I obtain bloody fluid following an atraumatic tap, if there is a residual abnormality postaspiration, or if requested by the patient. It has also been recommended that fluid be submitted for cytology when a repeat aspiration is done in a patient who presents with rapid reaccumulation of fluid. As mentioned previously, in addition to submitting aspirated fluid for cytology, when a residual abnormality is seen postaspiration, I do core biopsies through the residual lesion.

Cysts have a variable mammographic appearance. They are usually round or oval masses with marginal characteristics that range from well circumscribed to obscured, to indistinct (particularly when inflamed). Mural and intracystic calcifications (milk of calcium) may be present. On ultrasound, simple cysts are well-circumscribed, anechoic masses with posterior acoustic enhancement and thin edge shadows. Less common appearances include the presence of intracystic echoes that during real time are characterized by movement (e.g., “gurgling”), and persistent, nonmovable echoes that sometimes have an S-shaped (yin-yang sign) interface with the more anechoic portion of the cyst. If the cyst is small and deep in the breast, posterior acoustic enhancement may not be apparent.

Patient 7

What would you do to evaluate this patient?

When would you obtain a mammogram for a 20-year-old woman?

Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are our starting point in evaluating focal signs and symptoms in women under the age of 30 years or those who present during pregnancy or lactation regardless of age. A full mammogram is done only if breast cancer is suspected based on the clinical and ultrasound findings.

How would you describe the finding, and what is your differential?

What would you recommend next?

An oval, well-circumscribed complex cystic mass with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. Although the appearance is somewhat atypical for a cyst, this is the main diagnostic consideration. Alternative possibilities include a fibroadenoma, papilloma, and pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia. A galactocele, abscess, or posttraumatic or postsurgical fluid collection would be considerations in the appropriate clinical context. Although a cyst with atypical features is suspected, aspiration is undertaken.

The preaspiration image documents needle placement in the mass (Fig. 4.7B). A little less than 1 mL of serous fluid is aspirated. No residual abnormality is seen postaspiration (Fig. 4.7C). On ultrasound, simple cysts are described as anechoic, well-circumscribed masses with posterior acoustic enhancement and thin edge shadows. In some patients, however, cysts can be seen with internal echoes that shift in position as you image them in real time (i.e., gurgling cysts), persistent echoes that form an abrupt linear or S-shaped (yin-yang sign) interface with the cystic component of the mass, or high spicular echoes that do not shift in position. Gurgling cysts do not require aspiration unless the patient is symptomatic. Depending on your level of concern, relative to the latter two types of cysts, aspirations are not absolutely indicated.

Patient 8

What do you think?

A round mass is present in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast. The patient is called back for additional evaluation, which includes spot compression views and an ultrasound. Differential considerations at this point include cyst, fibroadenoma (complex fibroadenoma, tubular adenoma), phyllodes, papilloma, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, adenosis tumor, and focal fibrosis. Depending on the clinical context, sebaceous cyst, galactocele, postoperative or traumatic fluid collection, and an abscess are also in the differential. Given the seemingly circumscribed margins, malignancy is less likely; however, invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, medullary, mucinous, or papillary carcinoma, or metastatic disease, particularly if the patient has a known malignancy, are additional considerations.

Spot compression views (not shown) demonstrate a well-circumscribed mass with no associated calcifications. On ultrasound, a well-circumscribed, anechoic mass with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged, consistent with a simple cyst. In an asymptomatic patient, this requires no additional intervention or short-interval follow-up. The patient is reassured that what we are seeing is not cancer, that cysts do not turn into cancer, and that they are common, with many women developing them at various times.

BI-RADS® category 2: benign finding. Annual screening mammography is recommended.

What would you do next?

The mass in the left breast has enlarged. In determining the next appropriate step, I review the evaluation done the previous year. I focus on the ultrasound study. If, as in this patient, the ultrasound demonstrates a “classic” simple cyst, I do not call the patient back for a repeat evaluation. Cysts fluctuate in size, and as long the patient remains asymptomatic, I do not call the patient back. If, in reviewing the prior ultrasound there is any question about the diagnosis of a cyst (e.g., internal echoes, shadowing, or irregular margins), I will call the patient back for a repeat ultrasound.

BI-RADS® category 2: benign finding. Annual screening mammography is recommended.

Patient 9

How would you describe the findings, and what would you recommend next?

A well-circumscribed mass is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. On the tangential view, this appears to be a mixed-density lesion such that differential considerations include a lymph node, fat necrosis, hematoma, galactocele, or a fibroadenolipoma. The patient does not recall any recent trauma, and there is no history of a recent pregnancy.

How would you describe the findings, and what is your recommendation?

On physical examination a discrete, mobile, hard mass is palpated at the 10 o’clock position, 6 cm from the right nipple. A well-circumscribed, oval 1-cm mass that is nearly anechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. Although a cyst is suspected given the presence of internal echoes and following a discussion with the patient, an aspiration is undertaken.

The mass is atraumatically punctured using a 20G spinal needle and grossly bloody fluid is aspirated. Although several attempts are made to reposition the needle, no additional fluid is obtained and a residual abnormality persists. Core biopsies are done through the persistent abnormality. On inspection of the cores, a central area of hemorrhagic tissue (i.e., a lesion) is noted, on either side of which fatty tissue is seen. This correlates with what is seen mammographically: The lesion is surrounded by fat. The appearance of the cores, in conjunction with that of the aspirate, suggests either a hematoma or fat necrosis. The aspirated fluid is submitted for cytology and the cores are submitted for histologic evaluation. Predominantly blood and hemosiderin-laden macrophages are reported on the cytology. Fibroadipose tissue with granulation tissue, necrosis, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, chronic inflammation, fat necrosis, and foreign-body giant cells are reported on the cores. These findings are congruent with the clinical and imaging findings and the gross appearance of the cores. Annual mammography is recommended for this patient.

Patient 10

A round mass with partially well circumscribed margins is present in the right breast, corresponding to the site of clinical concern. The differential considerations for the mammographic findings in this patient include cyst, fibroadenoma (tubular adenoma, complex fibroadenoma), papillary lesion, focal fibrosis, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), adenosis tumor, and phyllodes tumor. Depending on the clinical context, galactocele, postoperative or traumatic fluid collection, and an abscess are also in the differential. Given the seemingly circumscribed margins, malignancy is less likely; however, invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, medullary, mucinous, or papillary carcinoma, or metastatic disease, particularly if the patient has a known malignancy, are additional considerations. An ultrasound is indicated for further evaluation.

How would you describe the findings, and what is your recommendation?

There is no history of a recent pregnancy, trauma, surgery, or significant tenderness. On physical examination, a hard but mobile mass is palpated at the 6 o’clock position, 2 cm from the right nipple. A well-circumscribed mass with internal echoes and posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding. Although a cyst is suspected, the echoes did not change in position during the ultrasound study and so an aspiration is undertaken. The mass is easily and atraumatically punctured, and approximately 8 mL of grossly bloody fluid is aspirated. No residual abnormality is seen postaspiration. The fluid is submitted for cytologic evaluation. Abundant red blood cells in a background of acellular debris are reported on the thin prep, and the cell block material is submitted for cytology. No malignant cells are identified.

The fluid reaccumulated in a matter of days. This, in combination with the bloody fluid obtained during the initial aspiration, suggests that further action is indicated. An excisional biopsy is performed, and an intermediate-grade, intracystic papillary carcinoma confined within a fibrous capsule (i.e., ductal carcinoma in situ) is reported on the excisional biopsy [pTis, pN0(sn), pMX; Stage 0]. There is no evidence of invasion. Atypical ductal hyperplasia is reported in the surrounding tissue.

Intracystic papillary carcinomas are rare, but they should be suspected if bloody fluid is aspirated following an atraumatic tap, if there is a residual abnormality following the aspiration, or if fluid reaccumulates rapidly. It is also important to emphasize that cytology is negative in a significant number (>.50%) of patients with intracystic carcinomas, so if there is a mural or intracystic component, core biopsies through these areas may be useful in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Patient 11

How should patients presenting with nipple discharge be evaluated?

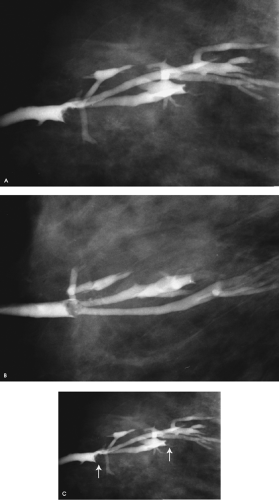

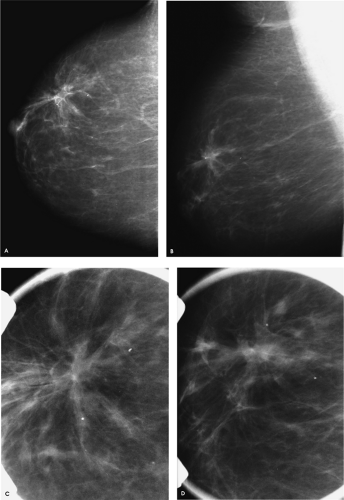

What do you think of this ductogram?

For patients presenting with nipple discharge, a full mammogram is done (images not shown for this patient), history is obtained, and a physical examination is done. If it is determined that the nipple discharge is spontaneous, a ductogram is done. In this patient, the cannulated duct is dilated (arbitrarily, we use the cannula as an internal reference for duct size; normal ducts are one to three cannulas in diameter) and there are two lesions in the duct. The anterior-most lesion is a filling defect; the second lesion is obstructing a side branch of the involved duct (Fig. 4.11C, arrows). These are likely to be papillomas, but excisional biopsy is recommended. Excisional biopsy in this patient confirms the presence of intraductal papillomas with no atypia or other associated proliferative changes.

Ultrasound is sometimes used to evaluate women with nipple discharge. It is important to recognize that this is useful when the lesion or lesions are close to the nipple and in a dilated duct. However, this is not always the situation. Intraductal lesions can be found several centimeters away from the nipple in nondilated ducts and therefore are not always identified by ultrasound.

Ductography can provide information relative to the course of the abnormal duct, the number and location of lesions, and the likely etiology of the lesions. It is not appropriate to assume, as many surgeons do, that lesions causing nipple discharge are in the subareolar area or that the ducts containing the lesions are dilated and therefore identifiable intraoperatively. Even if the abnormal duct is identifiable at the time of surgery, the number and location of potential lesions cannot be established reliably through visual inspection intraoperatively. When patients are taken to the operating room because of discharge but in the absence of preoperative evaluation, blind excisions are done, with no assurance that the cause of the discharge has been excised and evaluated histologically. Following duct excision, the discharge is usually eliminated. The patient may be relieved, but what have we accomplished if the underlying lesion, possibly a ductal carcinoma in situ, has not been excised?

What information is useful in evaluating women who present with nipple discharge?

Obtaining a good history is a helpful starting point in evaluating patients who present describing nipple discharge. We ask the patient: “How did you notice the discharge?” Invariably, patients with significant nipple discharge provide one, or all, of three descriptions: They notice dark brown spots in the cup of their bra, dark spots on their night clothes, or they have just gotten out of a hot bath or shower, dried their breasts, and notice fluid coming from their nipple. This is spontaneous nipple discharge, and regardless of its appearance (e.g., clear, serous hem-occult-negative or bloody), requires further evaluation. It should be contrasted with expressed nipple discharge that is physiologic in etiology and does not usually require additional evaluation. A variable amount of fluid is found in normal ducts, so nipple discharge can be obtained from multiple duct openings, bilaterally, in most women following vigorous breast and nipple manipulation.

The next step in evaluating women with nipple discharge is physical examination. A bright source of light (e.g., a halogen lamp) focused on the nipple and magnification of the nipple are helpful. I start by examining the surface of the nipple for any crusting or a duct opening that appears erythematous or more patulous than the others. These may be indicators of a duct opening that needs to be cannulated for ductography. I next use an alcohol wipe to clean the surface of the nipple (this clears any keratin plugs that may be partially or completely occluding the duct opening) and I examine the breast for any palpable mass. In doing the exam, I check to see if I am able to elicit discharge. In many patients with an intraductal lesion, it is possible to identify the trigger point described by Haagensen. When you apply pressure over the trigger point, discharge is elicited. As you move away from the trigger point, the discharge stops. In many patients with an intraductal lesion, the discharge is projectile (shoots out at you and can hit you in the eyes if you are not careful) and copious.

If the patient provides a history of spontaneous nipple discharge, and single-duct discharge is elicited on physical examination, a ductogram is undertaken even in women with hem-occult-negative discharge. If fluid is difficult to obtain, and it originates from multiple duct openings bilaterally, ductography is not indicated. We do not routinely submit nipple discharge for cytology, and we do not routinely do hem-occult testing. A negative cytology report does not exclude significant pathology, however, and if atypical cells are described, the issue of establishing the presence and location of a lesion in the duct remains.

There is a misconception that only bloody nipple discharge is significant. On the contrary, clear or serous hem–occult-negative discharge may reflect the presence of underlying ductal carcinoma in situ, so if nipple discharge is spontaneous, it warrants additional evaluation. Although ductography is not a perfect test and it is associated with a 15% false negative rate, ductography can be helpful in identifying the presence of one or multiple intraductal lesions, the location and course of the duct containing the lesions, and the extent of the lesion. It seems to be a more helpful study than doing cytology and blind surgical excisions that can potentially cut through tumor or leave a lesion in the breast while eliminating the presenting symptom. Duct openings are closely apposed on the surface of the nipple, so a 15% false negative rate for ductography is not surprising. If a normal ductogram is obtained in a patient with a history and physical examination that is highly suggestive of an intraductal lesion, I assume the normal ductogram is a false negative study and ask the patient to return in 1 week for a repeat study.

How is a ductogram done?

The secreting duct opening is cannulated using a blunt-tipped 30G straight sialography needle. As a starting point, 0.2 mL of contrast is injected into the duct. The cannula is left in the duct and taped onto the breast. Craniocaudal and 90-degree lateral magnification views of the breast are obtained. The initial amount of contrast injected is small, so that the subareolar portion of the duct can be evaluated. If more contrast is injected at the onset, the density of the contrast may mask small lesions close to the nipple, resulting in a false negative study. By leaving the cannula in the duct, additional contrast material can be injected as needed.

What are the common causes of spontaneous nipple discharge, and what are the more common findings on ductography?

Papillomas, fibrocystic changes, duct ectasia, and breast cancer (usually ductal carcinoma in situ) are the more common causes of spontaneous nipple discharge. Findings on ductography include one or multiple filling defects, duct obstruction, wall irregularity, displacement of the duct, extravasation, and duct dilatation.

What can be done preoperatively to assure excision of the abnormal duct, and how can we facilitate the histologic evaluation of intraductal lesions?

In addition to doing diagnostic ductograms to establish the presence, location, and extent of intraductal lesion, we also do preoperative ductograms. A methylene blue contrast (1:1) combination is injected into the duct on the day of surgery. The contrast allows us to verify that we have cannulated the previously evaluated duct (i.e., the duct with the intraductal lesions), and the methylene blue stains the duct for the surgeon and pathologist. Having the ability to identify the duct stained in blue intraoperatively can effectively limit the excision to the abnormal duct. Of equal importance is facilitating identification of the abnormal duct for the pathologist, because even if the duct is dilated intraoperatively, it collapses as the fluid drains out after excision. The methylene blue is used to identify the duct grossly and direct the dissection for identification of the lesion. Rarely, if the intraductal lesion(s) is peripheral in location (i.e., not in the subareolar area) or if it is in a small branch of the main duct, the ductogram is done the day of surgery and used to guide a mammographically guided preoperative wire localization.

Patient 12

What do you think?

What would you do next?

A predominantly fatty pattern is present, with axillary lymph nodes noted bilaterally. Scattered round calcifications, arterial calcifications, and a 1-cm mass with relatively well circumscribed margins and a round calcification are noted on the subareolar spot compression views. Given the described nipple discharge, a more detailed history of the discharge and a physical examination are indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree