Abstract

The aggressive growth and high recurrence rate of juvenile ossifying fibroma pose significant challenges in diagnosis and treatment. The lesion can expand substantially, involving the orbit and causing tooth displacement, leading to complications. We present the case of a 9-year-old boy with a 1-year history of progressively enlarging, painless swelling of the left cheek, accompanied by significant molar tooth displacement and a hyperglobus sign in the left eye. Histopathological examination ultimately confirmed the diagnosis of trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma. This case highlights the importance of considering maxillary ossifying fibroma in the differential diagnosis of orbital and periorbital masses. In such cases, in addition to assessing orbital involvement, the location and alignment of teeth should be carefully evaluated, as severe dental displacement, like in the present case, can occur.

Introduction

Juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF) is a rare, benign fibro-osseous lesion characterized by rapid growth and a high potential for recurrence. Most patients are diagnosed before the age of 15, and the condition affects both sexes equally. Although the maxilla is more commonly involved than the mandible, cases have also been reported in the orbit and skull [ ]. Clinical presentations vary depending on the affected site and often include pain and swelling. As the tumor enlarges, it can alter the facial contour, leading to asymmetry or deformity. In cases with large lesions, normal oral functions such as chewing and speaking may be compromised. Involvement of the alveolar bone can result in mobility and displacement of teeth, while lesions in the maxilla may extend into the maxillary sinus, causing symptoms such as congestion, infection, and nasal discharge. Additionally, maxillary ossifying fibromas can expand into the adjacent orbital cavity, leading to proptosis [ ]. In this article, we report the case of a patient with a maxillary JOF who was misdiagnosed and referred to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at Shiraz Dental School. The patient had been under ophthalmologic supervision for nearly a year due to unexplained left hyperglobus.

Case presentation

A 9-year-old male patient was referred to the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery at Shiraz Dental School in December 2023 with a chief complaint of left cheek swelling and a hyperglobus of the left eye. Hyperglobus was the first symptom noted about a year ago, and the patient had been under ophthalmologic observation during that period. Six months later, swelling of the left cheek developed, with a marked increase in severity over the last 3 months. On extraoral examination, a painless swelling with a bony hard consistency was observed on the left cheek. The overlying skin appeared normal in texture and color; however, the patient reported numbness in the left cheek area and weakness in the movement of the left upper lip. No other neurological deficits were noted, and there were no visual disturbances or diplopia, with ocular motility remaining intact ( Fig. 1 ). Intraoral examination revealed an expansion of the left maxillary ridge along with mobility of primary teeth numbered c, d, and e.

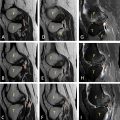

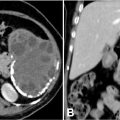

A panoramic radiograph and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) were obtained to evaluate the lesion further. Imaging demonstrated a significantly large, well-circumscribed, expansile, heterogeneous (mixed-density) mass—suggestive of both fibrous and osseous components—occupying the entire left maxillary sinus area. The mass affected the nasal cavity, causing deviation and destruction of the nasal septum; invaded the ethmoid sinus; and led to thinning, displacement, and perforation of the anterior wall of the sphenoid sinus. Additionally, the lesion extended into the pterygopalatine fossa with associated destruction of the pterygoid plates. Significant elevation and perforation of the left infraorbital rim were also evident. Extreme postero-superior displacement of the second molar tooth toward the inferior orbital fissure was observed, resulting in a blockage of the fissure. Furthermore, compromise of the nasopharyngeal space was noted ( Figs. 2 and 3 ).

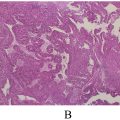

Before any invasive procedure—whether an incisional biopsy or the complete excision of the lesion—a detailed medical history was obtained and several blood tests were performed. The patient’s history revealed seasonal allergic reactions and G6PD deficiency, and his blood pressure was documented as 10/5 mmHg. Coagulation studies (PT, PTT, and INR) were within normal limits. The complete blood count (CBC) revealed the following: WBC: 19 × 10³/μl, RBC: 3.66 × 10⁶/μl, Hb: 10.6 g/dl, Hct: 33.2%, and MCHC: 31.9 g/dl. Other laboratory tests—including blood sugar, BUN, creatinine, calcium, serum sodium, serum potassium, albumin, and magnesium—were completely normal. An intraoral incisional biopsy was performed under local anesthesia. We selected mepivacaine to minimize the risk of methemoglobinemia due to the patient’s G6PD deficiency. The biopsy specimen was submitted for pathological evaluation with a differential diagnosis of fibrous dysplasia and ossifying fibroma based on clinical and radiologic evaluation. The definitive diagnosis of juvenile ossifying fibroma was established. Histological sections revealed a well-circumscribed tumor composed of trabeculae of bone embedded within a cellular fibrous connective tissue background, consistent with the trabecular form of juvenile ossifying fibroma ( Fig. 4 ).