Anal cancer represents a rare type of gastrointestinal malignancy with anal squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histologic type. This review aims to present up-to-date imaging recommendations for anal cancer, including for baseline staging and follow-up assessment after treatment, with an emphasis on the role of MR imaging. Treatment complications are also discussed, helping to familiarize radiologists to include them in their search patterns. Lastly, a short discussion on the future horizon of anal cancer imaging is presented.

Key points

- •

Anal cancer (squamous cell carcinoma) is a rare type of gastrointestinal malignancy with similar imaging features to its rectal neighbor (ie, rectal cancer); however, both entail distinct tumor, node, and metastasis staging systems and treatments.

- •

Many societies recommend MR imaging for staging anal cancer; however, the literature also suggests the benefits of PET/computed tomography particularly for evaluating the lymph nodes (N-staging) and for posttreatment follow-up.

- •

On restaging imaging, it is important to assess response in the primary tumor and lymph nodes as well as to be aware of complications from both the tumor itself as well as treatment.

Introduction

Anal cancer is considered an uncommon malignancy. In the United States, the American Cancer Society estimates only 10,540 new cases in 2024, equivalent to 0.5% of all new cancers. Based on data from 2017 to 2021, the annual incidence rate of anal cancer was 1.9 per 100,000 men and women in the United States, and based on data from 2018 to 2022, the annual mortality rate was 0.4 per 100,000 men and women. Anal cancer is seen more frequently in women than in men, with affected women outnumbering affected men by a ratio of approximately 2:1. Despite remaining rare compared with other malignancies, 20 years of data from 2001 to 2020 show an increasing annual incidence rate of anal cancer in adults aged older than 44 years, which is expected to rise even further in the future. Anal squamous cell carcinoma (ASCC) is the most common histologic type of anal cancer, with human papillomavirus infection as the most common risk factor for this histologic type, especially in the immunocompromised population. Other malignant and benign conditions can also arise from the anal canal, including anal adenocarcinoma (most commonly diagnosed after ASCC), primary anorectal melanoma, anal margin cancer, lymphoma, gastrointestinal tumor, and benign findings such as leiomyoma and schwannoma.

Until the late 1970s, the first-line treatment of anal cancer was abdominoperineal resection. The groundbreaking report by Nigro and colleagues in 1974, however, showed the feasibility of achieving pathologic complete response after preoperative treatment with chemotherapy and radiation (30 Gy with concurrent 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C). These findings set the foundation for treating ASCC primarily with chemoradiation therapy (CRT), without the need for surgery in patients who achieve a complete response, which is seen in 80% to 90% of cases. The efficacy of CRT rendered surgery necessary for only T1M0 disease or for salvage purposes when CRT has failed. Conventional radiotherapy was later replaced by intensity-modulated radiation therapy, which showed equivalent potency but with the added benefit of decreased acute and long-term toxicity.

This review aims to present up-to-date imaging recommendations for anal cancer, including for baseline staging and follow-up assessment after treatment, with an emphasis on the role of MR imaging. Treatment complications are also discussed, helping to familiarize radiologists to include them in their search patterns. Lastly, a short discussion on the future horizon of anal cancer imaging is presented.

Anatomy

The “anatomic anal canal” represents the terminal 3- to 5-cm portion of the intestine that extends from the anal verge to the dentate line/valves of Morgagni. The dentate line is an important anatomic landmark that serves as the transition between intestinal columnar cells and anal squamous epithelium. Different venous and lymphatic drainage patterns above and below the dentate line are responsible for the unique pattern of nodal and metastatic spread of anal cancer.

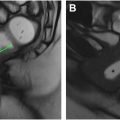

Because the dentate line is not readily visible on imaging and is not palpable on physical examination, physicians often describe findings related to the “surgical anal canal” rather than the “anatomic anal canal.” The “surgical anal canal” refers to the portion of the intestine that extends from the palpable anorectal ring formed by the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscles to the anal verge. The anal sphincter is made up of the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and the external anal sphincter complex (EAS; Fig. 1 ). The IAS is the extension of the thickened inner circular muscle of the rectal muscularis propria. The EAS comprises the levator ani, the puborectalis, and the external sphincter muscle, all of which are skeletal muscles under voluntary control. The intersphincteric plane, that is, the space between the IAS and EAS, is formed by the conjoint longitudinal muscle of the rectum and is an important landmark for determining potential surgical resectability of low rectal cancer involving the anal canal.

MR imaging technique

High-resolution MR imaging sequences provide superior soft tissue resolution to evaluate the anal canal, including identifying tumor location and accurately assessing the T-stage of anal SCC based on tumor size and any involvement of adjacent organs. The same MR imaging protocol may be used for baseline staging and restaging. A magnetic field of 1.5 T or greater with surface-based array coils is necessary for accurate local staging. Endorectal coils are not recommended due to patient discomfort, potential for bleeding, and the high risk of anal canal stenosis. , Specific patient preparation is unnecessary, but the use of a microenema and a spasmolytic agent (butylscopolamine or glucagon) can decrease imaging artifacts.

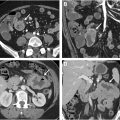

A large field-of-view extending from the aortic bifurcation to the anal margin, including the inguinal region, is essential to assess the locoregional and superior nodal stations. High-resolution, small field-of-view 2-dimensional T2-weighted imaging in 3 planes is essential to determine tumor size and assess the relationship of the tumor to adjacent organs. Coronal images are obtained parallel to the long axis of the tumor/tumor bed/anal canal while axial images are obtained orthogonally, all with a slice thickness of up to 3 mm. Axial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), with b-values of 0, 800, and 1500 s/mm 2 , is recommended in MR imaging protocols for anal and rectal cancer, improving the overall sensitivity of MR imaging in both baseline staging and restaging, especially in the setting of the smaller and recurrent lesions, and can aid in the detection of lymph nodes ( Fig. 2 A–D ). ,

There is no consensus on the application of intravenous contrast, which can sometimes aid the detection of tumor-related complications (eg, fistula and abscess), especially in the posttreatment setting.

Baseline staging

Clinical evaluation for the initial assessment of anal cancer includes the following :

- •

Physical inspection of the perianal region for visible and protruding parts of the tumor.

- •

Digital rectal examination to assess the approximate size of the tumor, sphincter status, local invasion, and perirectal adenopathy.

- •

Inguinal palpation to determine any inguinal nodal involvement.

- •

Vaginal examination to determine the presence of anovaginal fistula.

- •

Proctoscopy with tissue sampling under anesthesia.

Following clinical evaluation, imaging, most commonly MR imaging and/or PET/computed tomography(CT), is performed for the purpose of baseline staging. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging system is used to stage anal cancer based on tumor size and local organ involvement (T), regional nodal involvement (N), and the presence of distant metastasis (M; Table 1 ). The subsections below detail the T-staging, N-staging, and M-staging of anal cancer.

| Primary tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (previously termed carcinoma in situ, Bowen disease, anal intraepithelial neoplasia II–III, and high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia) |

| T1 | Tumor ≤2 cm |

| T2 | Tumor >2 cm but ≤5 cm |

| T3 | Tumor >5 cm |

| T4 | Tumor of any size invading adjacent organ(s), such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder |

| Regional lymph nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal, internal iliac, or external iliac nodes |

| N1a | Metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal, obturator, or internal iliac lymph nodes |

| N1b | Metastasis in external iliac lymph nodes |

| N1c | Metastasis in external iliac with any N1a nodes |

| Distant metastasis (M) | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| cM0 | No distant metastasis |

| cM1 | Distant metastasis |

| pM1 | Distant metastasis, microscopically confirmed |

T-staging

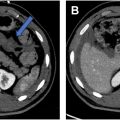

Typically, the tumor bulk of anal cancer is within the anal canal, with the tumor extending to the rectum and perianal region in some cases. Rarely, multifocal anorectal involvement can occur in patients with ulcerative colitis and immunodeficiency, with the tumor originating from condylomas or pre-existing anal intraepithelial neoplasms; also, additional rectal wall involvement can occur above the tumor bulk ( Fig. 3 A–C ). Anal cancer has a similar imaging appearance to the more common adjacent rectal cancer including intermediate T2 signal (higher than that of skeletal muscles and lower than that of ischioanal fat) and diffusion restriction, making a histologic report of SCC crucial before radiological staging.

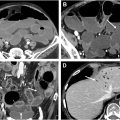

Stages T1 to T3 are assigned based on the largest size of the tumor measured on any plane, and stage T4 is assigned if there is any involvement of an adjacent organ (eg, vagina, urethra, uterus, prostate, or bladder) regardless of size ( Fig. 4 A–D ). Involvement of the anal sphincter complex, levator ani, puborectalis muscles, or the rectum does not affect T-staging. Tumor size larger than 5 cm and involvement of an adjacent organ have been found to be associated with a worse prognosis. ,