Muscle Tumors

Muscle tumors of the soft tissue are uncommon. It is difficult to establish their prevalence, but it is estimated that benign muscle tumors make up less than 2% of all benign soft tissue tumors (1), while rhabdomyosarcoma and leiomyosarcoma account for approximately 2% to 12% and 8% to 9%, respectively, of all classified soft tissue sarcomas (2, 3, 4). This chapter discusses the spectrum of benign and malignant muscle tumors, including leiomyoma, rhabdomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Although not considered a musculoskeletal lesion, the gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is also discussed briefly.

BENIGN MUSCLE TUMORS

Leiomyoma

Leiomyomas are quite unusual outside of the uterus and gastrointestinal tract (5, 6). In a study by Farman (7) of 7,748 lesions, approximately 95% of leiomyomas occurred in the female genital tract. The remainder were scattered over various anatomic locations, although almost 75% of these occurred in the skin. These results, based on surgical material, likely underestimate the large number of asymptomatic gastrointestinal and genitourinary lesions identified at autopsy (8). When in the soft tissues, leiomyomas are usually small and cutaneous or subcutaneous; consequently, they are not the subject of radiologic imaging. Rarely, leiomyoma may be encountered in the deep soft tissue. These deep lesions are much larger than their superficial counterparts and much more likely to be confused with leiomyosarcoma, which is considerably more common.

It is difficult to estimate the incidence of soft tissue leiomyoma accurately, but in the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) experience, these tumors accounted for approximately 1.7% of 18,667 benign soft tissue tumors (1). Hachisuga et al. reported an incidence of 4.4% in a review of 12,663 benign soft tissue tumors in the pathology registry of Kyushu University (9).

Classification

Smooth muscle is widely distributed throughout the body, to include the skin (10). Soft tissue leiomyomas are usually subdivided into several distinct clinical groups (8, 10). The most common form is the cutaneous leiomyoma (leiomyoma cutis). This lesion arises from the arrector pili muscle of the skin and the deep dermis of the scrotum (dartoic muscles), labia majora, and nipple (8). Lesions arising from the deep dermis of the genital regions are collectively termed genital leiomyomas (8). The second group of leiomyoma is the angioleiomyoma, also

known as angiomyoma or vascular leiomyoma. This lesion is differentiated from the cutaneous form by its subcutaneous location and histology, which is dominated by a conglomeration of thick-walled vessels associated with smooth muscle tissue (8). The leiomyoma of deep soft tissue is the final type and the one that more typically presents as a musculoskeletal mass. This lesion is much larger than the cutaneous and subcutaneous forms and the most likely to be confused with a leiomyosarcoma (8).

known as angiomyoma or vascular leiomyoma. This lesion is differentiated from the cutaneous form by its subcutaneous location and histology, which is dominated by a conglomeration of thick-walled vessels associated with smooth muscle tissue (8). The leiomyoma of deep soft tissue is the final type and the one that more typically presents as a musculoskeletal mass. This lesion is much larger than the cutaneous and subcutaneous forms and the most likely to be confused with a leiomyosarcoma (8).

KEY CONCEPTS

For musculoskeletal purposes, leiomyoma is classified into three groups, although others are described:

Leiomyoma cutis (cutaneous leiomyoma): small lesions arising in skin.

Vascular leiomyoma (angioleimyoma): small to moderate size lesions arising in subcutaneous tissue.

Deep leiomyoma of soft tissue: large lesions in deep soft tissue.

Weiss and Goldblum (8) also noted that leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata and intravenous leiomyomatosis are also classified as benign leiomyomas. They noted that the former is considered a metaplastic response of the peritoneal surface, characterized by multiple smooth muscle nodules, whereas the latter represents intravenous extension of uterine leiomyoma. These lesions are clearly outside the realm of the musculoskeletal radiologist and are not discussed here. The term lipoleiomyoma may be used to describe the rare lesion characterized by mature smooth muscle and mature adipose tissue. This lesion is discussed in Chapter 4, under the section entitled myolipoma.

Cutaneous leiomyomas are superficial and usually removed without preoperative imaging. The subsequent discussion mentions these superficial lesions only briefly, emphasizing the deep leiomyoma and the typically subcutaneous angioleiomyoma, which are more likely to be confused with a sarcoma and imaged.

Superficial Leiomyoma

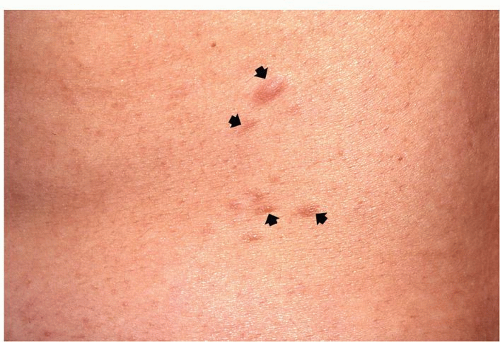

Superficial (cutaneous) leiomyomas typically arise in association with the smooth muscle of the skin. Those lesions arising from the pilar arrector muscles are termed piloleiomyomas. They typically occur as clustered papules or, less commonly, as single nodules ranging in size from a few millimeters to 2 cm (Fig. 7.1) (10, 11). Single lesions tend to be larger (11). Pilar leiomyomas are most common in young adults, on the hair-bearing extensor surfaces of the arms and legs (10, 11, 12). Lesions are typically painful, eliciting a burning or pinching sensation (8, 11, 12). Two or more body areas are usually involved in the majority of patients (10). Superficial leiomyomas may also arise from the deep dermis of the scrotum, nipple, areola, and vulva, and in these areas they are termed genital leiomyomas (8). In contrast to piloleiomyomas, genital leiomyomas are usually asymptomatic, with pain and tenderness possibly associated with touch, trauma, emotion, or pressure (10). Superficial leiomyomas are usually dermatologic lesions and uncommonly evaluated radiologically (13).

Angioleiomyoma (Angiomyoma, Vascular Leiomyoma)

Angioleiomyoma is a solitary lesion, probably arising from the tunica media of the vein (12, 14), composed of a conglomerate of thick-walled vessels, which are associated with smooth muscle (8). Angiomyoma is subcutaneous and represents approximately half of all superficial leiomyomas (8). The term vascular leiomyoma was adopted by Stout (15) in 1937 to distinguish these subcutaneous lesions from the cutaneous form, which is characterized histologically by thin-walled, inconspicuous vessels (8). In 2013, the WHO reclassified angioleiomyoma as a pericytic (perivascular) tumor noting that a morphological continuum exists between angioleiomyoma and myopericytoma, a perivascular myxoid neoplasm (16).

Angioleiomyoma is most common in adults, with two-thirds occurring in patients in the fourth through sixth decades of life (9), although they have been reported in children (16, 17). Women are reported to be affected more commonly than men (1.7-2.2:1) (9, 14); however, there is a male predilection (2.1:1) in the AFIP experience (1). The lesion is typically small, less than 2 cm, and located in the extremities in 89% to 94% of cases, with the lower extremity most frequently involved (approximately 50% to 75% of extremity cases) (1, 9, 14, 18). Because the foot is a common location, patients may present with complaints related to problems with footwear (19, 20). Pain and tenderness are found in more than half of the patients and may be initiated with changes in temperature, pressure, pregnancy, or menses (18, 21). Symptoms may be initiated by light touching or scratching (18). Lesions are often slowly growing and may be present for 10 to 15 years prior to presentation (19, 22).

Grossly, angioleiomyoma is typically a well-defined, circumscribed, gray-white nodule (8). It is composed of smooth muscle tissue with prominent thick-walled vessels. Areas of myxoid change, hyalinization, calcification, and fat can be seen (8), although it has been our experience that these histologic features are not well-delineated on imaging.

Leiomyoma of the Deep Soft Tissue

Leiomyoma of the deep soft tissue is quite uncommon in comparison to the superficial forms. The existence of this rare entity has been questioned because long-term follow-up studies revealed that some lesions initially diagnosed

as leiomyoma subsequently proved to be malignant (4, 8). Although current evidence supports the existence of this lesion, the diagnosis must be made in accordance with strict adherence to established histologic criteria (4). Soft tissue leiomyomas are of two distinct types: somatic and gynecologic (8). Only the former is discussed here.

as leiomyoma subsequently proved to be malignant (4, 8). Although current evidence supports the existence of this lesion, the diagnosis must be made in accordance with strict adherence to established histologic criteria (4). Soft tissue leiomyomas are of two distinct types: somatic and gynecologic (8). Only the former is discussed here.

Leiomyoma of the deep soft tissue is a lesion of adults and is typically located in the deep soft tissue of the extremities or retroperitoneum (8, 23). Billings et al. (23) reviewed their experience with 36 cases of leiomyoma seen in consultation at Emory University. These investigators confirmed that deep leiomyoma occurs in two distinct locations: the deep somatic soft tissue of the extremities (n = 13) and the retroperitoneum (n = 23; 3 of which occurred in the abdomen). They also noted that extremity lesions affected both sexes equally, whereas retroperitoneal lesions occurred almost exclusively in women (22 women, 1 man), suggesting two distinct subtypes: the deep leiomyoma of somatic soft tissue and the retroperitonealabdominal leiomyoma. This latter form likely arises from hormonally sensitive smooth muscle and is similar to uterine leiomyoma. Deep leiomyomas are usually large at presentation, suggesting that they produce few symptoms (8).

In a review of the literature in 2000, Misumi et al. (24) found 21 previously reported cases. They found a mean patient age of 25 years (range: 3 to 62 years), with men affected twice as often as women. Almost half of the lesions (48%) were located in the extremities and only a single patient had multiple lesions.

Grossly, leiomyoma of the deep soft tissues is a welldefined, circumscribed, nodular, gray-white mass that may have a gelatinous appearance (25, 26, 27). Microscopy shows a lesion composed of smooth muscle that may demonstrate rich vascularization (25). The lesion is histologically similar to its superficial counterparts, except it is larger and more prone to undergo regressive change, including fibrosis, calcification, and, rarely, ossification (8). It must be emphasized that most deep smooth muscle tumors are leiomyosarcomas, and the diagnosis of leiomyoma requires the absence of microscopic evidence of significant cellular pleomorphism or mitotic activity (8). Although the distinction between leiomyoma of the deep soft and leiomyosarcoma can usually be made on the basis of histologic criteria, there are some retro-peritoneal lesions which will demonstrate sufficiently increased mitotic activity to warrant the classification of uncertain malignant potential (4).

Imaging of Leiomyoma

Superficial Leiomyoma

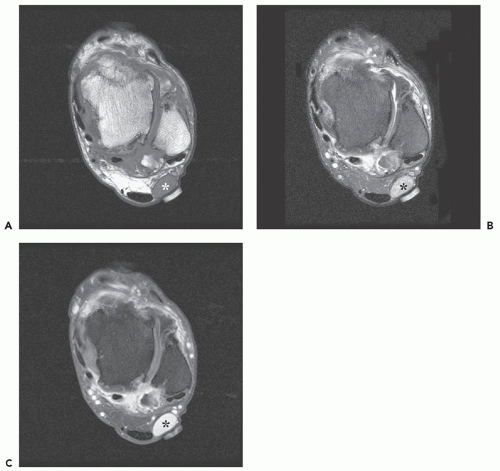

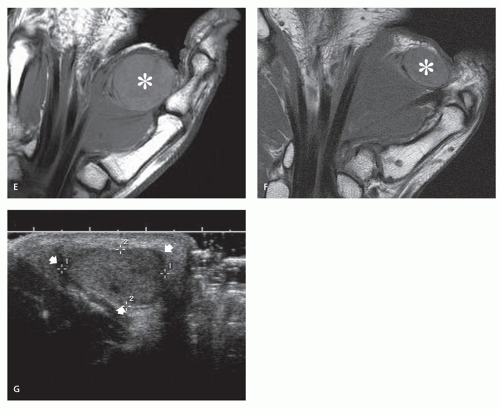

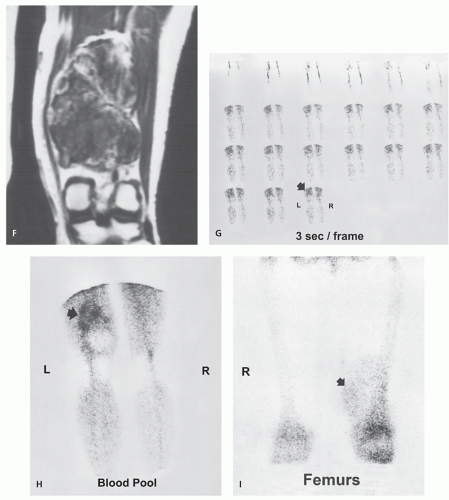

As previously noted, the superficial piloleiomyoma and genital leiomyoma are rarely imaged. A few case reports document the appearance of genital leiomyoma of the testis as a nonspecific, solid, hypoechoic mass with moderate color Doppler flow (Fig. 7.1) (28, 29). In contrast, the imaging appearance of angioleiomyoma is well-documented. Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging shows the lesion to be a well-defined, round to oval, subcutaneous, or dermal mass with signal intensity similar to or slightly hyperintense to that of skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images. On T2-weighted images, lesions demonstrate heterogeneous high signal intensity or mixed signal intensity with areas isointense to mildly hyperintense to that of skeletal muscle (17, 18, 19, 22, 30, 31, 32). Yoo and colleagues, in a report of eight cases, noted a peripheral rim of low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images which corresponded to a fibrous pseudocapsule on pathologic examination (17). Prominent homogeneous and heterogeneous enhancement following contrast administration is reported (18, 19, 22, 30), with Yoo et al. (17) also reporting an enhancing tubular structure adjacent to the mass in seven of eight cases (88%), thought to represent an associated vessel (Figs. 7.2, 7.3, 7.4). Multiple vascular tubular and round signal voids have also been noted (18, 33). The vascular nature of the lesion may also be identified on Tc-99m red blood cell perfusion and blood-pool scintigraphy (34).

KEY CONCEPTS

Typical MR imaging:

Well-defined mass.

T1-weighted images show intermediate signal intensity, similar to or slightly hyperintense to that of skeletal muscle.

T2-weighted images show variable heterogeneous signal intensity, with areas ranging from hypointense to hyperintense to that of skeletal muscle.

Prominent enhancement following intravenous contrast.

CT imaging:

Well-defined mass when subcutaneous; variable margin when deep.

Attenuation similar to that of skeletal muscle.

Enhancement following intravenous contrast.

Radiographs:

Radiographs typically show a nonspecific mass.

Calcification is more common in deep than in superficial lesions.

Three patterns of calcification have been described in deep soft tissue leiomyoma: scattered small flecks or sand-like calcification, plaque-like calcification, and large mulberry-like calcification (similar to fibroid).

Large calcifications within the lesion will appear as signal voids within the mass.

Ultrasound of angioleiomyoma will show a solid, ovoid, well-defined mass with a relatively homogeneous, hypoechoic echotexture and a small amount of posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 7.4G) (35, 36). Evaluation with color Doppler will demonstrate prominent hypervascularity and may demonstrate associated feeding vessels (35, 36). A thickened capsule with increased vascularity on power Doppler has also been described (32). Radiographs in patients with angioleiomyoma are typically

nonspecific. Calcifications have been reported, and may be extensive, but are more characteristically seen in deep leiomyoma of soft tissue (see next paragraph) (Fig. 7.5) (37). Cortical scalloping of the adjacent bone has also been reported (16).

nonspecific. Calcifications have been reported, and may be extensive, but are more characteristically seen in deep leiomyoma of soft tissue (see next paragraph) (Fig. 7.5) (37). Cortical scalloping of the adjacent bone has also been reported (16).

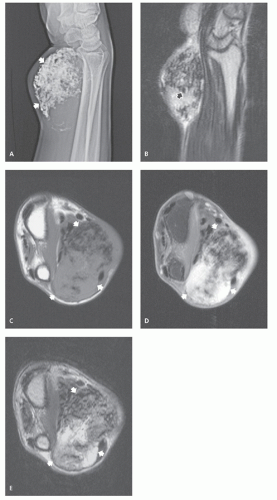

Deep Leiomyoma of Soft Tissue

There is little radiologic literature on the appearance of deep soft tissue leiomyoma. Scattered calcification, which is likely dystrophic (38, 39) and secondary to involutional change, is not uncommon and is seen in approximately 70% of cases, reported by Misumi et al. in 7 of 10 cases (24) and by Miki and colleagues in 12 of 17 cases (26). Three distinct patterns of calcification are noted, although they may coexist within a single lesion (5): scattered small flecks or sand-like calcification, plaque-like calcification, and large mulberry-like calcification (similar to that noted in uterine leiomyoma) (Fig. 7.6). Lubbers et al. (5) suggested this may represent a spectrum of regressive change, with the sand-like calcification representing the earliest change and the mulberry-like calcification representing more advanced degeneration. The mulberry-like calcification is the most common and the most characteristic (24). Although radiographically detectable calcification is common in adults, it is rare in patients younger than 16 years, but has been reported (40, 41). Extensive metaplastic ossification, which is assumed to be rare, has also been noted (42, 43).

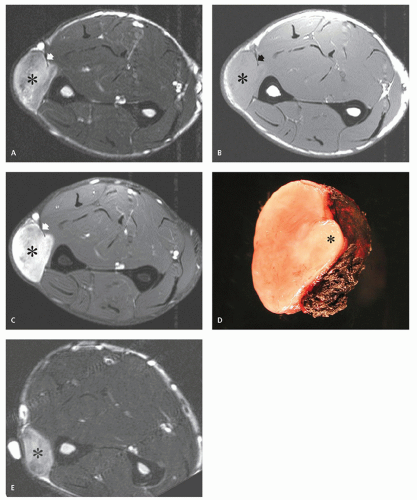

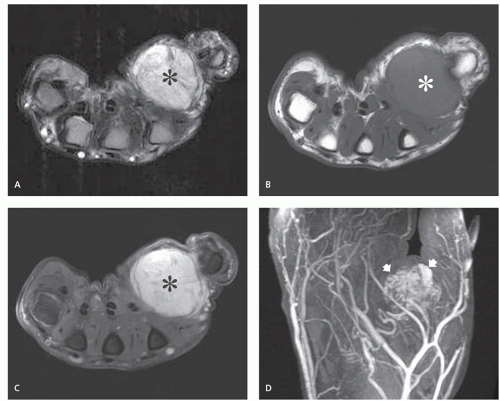

MR experience with this lesion is extremely limited, with MR demonstrating a nonspecific, well-defined soft tissue mass. On T2-weighted sequences, a deep leiomyoma may demonstrate a variable appearance with low, intermediate, and high signal intensities noted (19, 24, 26, 40, 42). The lesion markedly enhances following contrast administration (24, 26, 39, 42). Enhancement is usually, but not necessarily, homogeneous, and a pattern of peripheral enhancement has also been reported (44). Miki et al. reported the dynamic enhancement features in a lesion of the great toe, noting a rapid ascending slope followed by gradually descending slope, reflecting the vascularity of the lesion (26). Large calcifications within the lesion appear as signal voids within the mass. This great variability

in MR appearances parallels that seen in uterine smooth muscle tumors (Fig. 7.6) (45).

in MR appearances parallels that seen in uterine smooth muscle tumors (Fig. 7.6) (45).

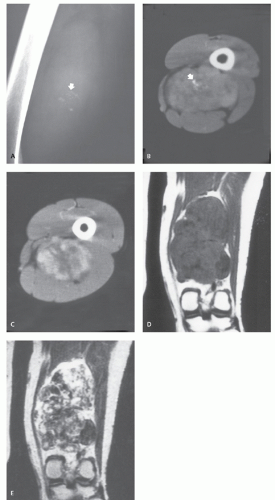

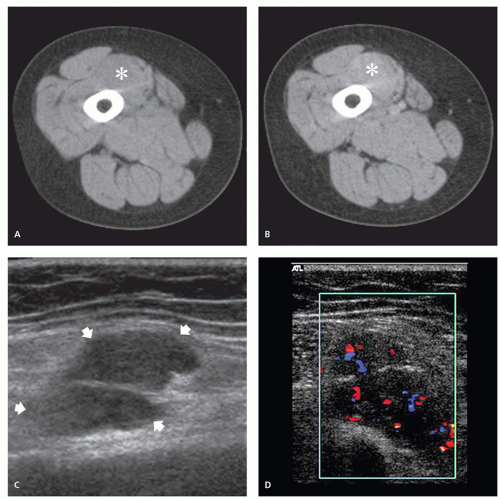

On computed tomography (CT), the lesion has soft tissue attenuation. Margins are variable, with some well-defined and others poorly delineated; the latter is more likely when the lesion arises within muscle (5, 24, 25). Following intravenous contrast enhancement, the lesion may show irregular or peripheral enhancement

(Fig. 7.7) (24, 25). Calcification within the lesion is well seen on CT. Large conglomerate calcifications may mimic mineralization in cartilage lesions (39). Our limited experience with the ultrasound appearance of deep leiomyoma has shown that it is similar to that of angioleiomyoma, showing a solid, relatively well-defined mass with a relatively homogeneous, hypoechoic echotexture, and a small amount of posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 7.7).

(Fig. 7.7) (24, 25). Calcification within the lesion is well seen on CT. Large conglomerate calcifications may mimic mineralization in cartilage lesions (39). Our limited experience with the ultrasound appearance of deep leiomyoma has shown that it is similar to that of angioleiomyoma, showing a solid, relatively well-defined mass with a relatively homogeneous, hypoechoic echotexture, and a small amount of posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 7.7).

Rhabdomyoma

Originally described in 1864 and termed rhabdomyoma purum, rhabdomyoma is a rare benign tumor composed of striated muscle cells (46, 47). Although rhabdomyomas make up approximately 2% of muscle tumors (47), only 115 extracardiac rhabdomyomas were reported in the literature through 1988 (48). In a review of 18,677 benign soft tissue tumors at the AFIP, only 15 (0.1%) rhabdomyomas of soft tissue (extracardiac) were noted (1).

Classification

Rhabdomyoma is classified into cardiac and extracardiac types on the basis of location (49). More than half of those patients with cardiac rhabdomyoma have tuberous sclerosis (50), and it is this association that suggested to some investigators that cardiac rhabdomyoma is

a hamartomatous lesion (51). Unlike cardiac rhabdomyoma, extracardiac rhabdomyoma is not associated with tuberous sclerosis and likely represents a true neoplasm (49, 52). Because only the extracardiac type may present as a musculoskeletal mass, cardiac lesions are not addressed here.

a hamartomatous lesion (51). Unlike cardiac rhabdomyoma, extracardiac rhabdomyoma is not associated with tuberous sclerosis and likely represents a true neoplasm (49, 52). Because only the extracardiac type may present as a musculoskeletal mass, cardiac lesions are not addressed here.

Extracardiac rhabdomyoma is primarily subclassified into adult and fetal types, depending on the degree of differentiation (49, 53). Rarely, rhabdomyoma may occur in the genital tract (genital rhabdomyoma) (51). Although it is convenient to subclassify extracardiac rhabdomyoma, lesions may show overlapping microscopic features, suggesting that they are a single group with a spectrum of rhabdomyoblastic differentiation (54).

KEY CONCEPTS

Classified into cardiac and extracardiac types.

Extracardiac rhabdomyoma further classified into adult, fetal, and genital types.

Extracardiac rhabdomyoma is not associated with tuberous sclerosis.

Adult Rhabdomyoma

The adult rhabdomyoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor with mature skeletal differentiation (49). Although it may occur at any age, the tumor is found most often in middleaged men, with a mean age in the sixth decade. The male predominance is strong at 2 to 5:1 (47, 48, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56, 57). Adult-type rhabdomyoma is rare in children (58).

Adult rhabdomyomas are most commonly seen in the head and neck (90%) and may derive from the musculature of the third and fourth branchial arches (59, 60, 61), because they are reported most frequently in the larynx, pharynx, and mouth (47, 57, 62, 63, 64). Less frequent sites of involvement include the cheek, orbit, tonsil, and lip (63, 65, 66, 67); rare cases are reported in the somatic skeletal muscles. Rhabdomyoma may present as a circumscribed intramuscular mass of the tongue or lateral

muscles of the neck (47, 62). A lesion presenting in the somatic skeletal muscle may mimic a soft tissue sarcoma. Osseous structure may be remodeled from the adjacent soft tissue mass, but osseous destruction is absent (68).

muscles of the neck (47, 62). A lesion presenting in the somatic skeletal muscle may mimic a soft tissue sarcoma. Osseous structure may be remodeled from the adjacent soft tissue mass, but osseous destruction is absent (68).

The lesion is typically a slow-growing, solitary, asymptomatic, polypoid mass. Symptoms may include upper airway obstruction and are often long standing, with a median duration of 2 years (49).

Multiple tumor nodules in the same anatomic site are seen in approximately 25% of cases (69); however, true multifocal lesions are unusual, representing approximately 4% of lesions (1, 48, 70). Bilateral pharyngeal wall lesions are reported (71). Surgery is curative (48, 56), although recurrence following surgery may be caused by incomplete excision or a second lesion arising in the same location (70). Local recurrence rates as high as 42%

are reported (60). There are no reported cases of malignant transformation (49, 71).

are reported (60). There are no reported cases of malignant transformation (49, 71).

Grossly, lesions are typically brown, lobulated masses (72). Microscopically, lesions are composed of round to polygonal cells with abundant clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm. Adult rhabdomyomas are strongly periodic acid-Schiff positive, reflecting a high glycogen content (72). Thin and thick filaments (myosin and actin) are dispersed randomly, and the lesions have features of disorganized skeletal muscle cells (72). Cross-striations are readily detected (6). Immunohistochemistry is useful to identify myoglobin, desmin, or both (48), with desmin being the most reliable marker to identify smooth or skeletal muscle differentiation (48).

Fetal Rhabdomyoma

The fetal rhabdomyoma, less common than the adult form, is a tumor that exhibits immature skeletal muscle differentiation (47, 48, 49, 54). It was first described in 1972 by Dehner and colleagues in a report of nine cases from the AFIP (73). Fetal rhabdomyoma is usually seen in children, with a median age at presentation of 4 years (47, 48, 49, 54). Congenital cases are reported, but are rare (74). Boys are affected much more commonly than girls, approximately 2.4:1 (49, 51, 53, 54). As is the case with adult rhabdomyoma, the lesion is most common in the head and neck, most often presenting as a welldefined, subcutaneous nodule in the posterior auricular region (54, 55, 75); however, it may also be located in a distribution similar to that of the adult form (55). Lesions are treated by surgical excision and local recurrence is rare but well-documented. Walsh and Hurt reported a case of a superficial chin lesion in a 1-year-old, excised with positive microscopic margins, which remained stable without progression over 54 months of observation (76). Metastases are not reported (49).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree