Pediatrics

Jeanne G. Hill

Paul Thacker

Anil G. Rao

The authors and editors acknowledge the contribution of the Chapter 1 author from the third edition: Paula Keslar, MD.

Case 1.1

HISTORY: A 3-day-old infant with acute onset of bilious vomiting

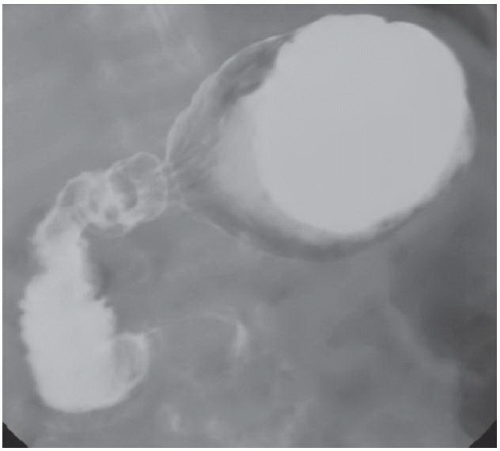

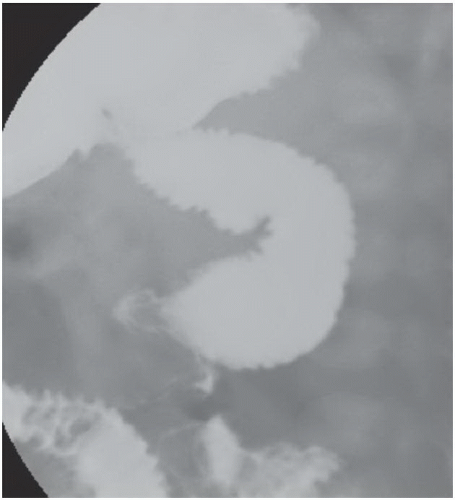

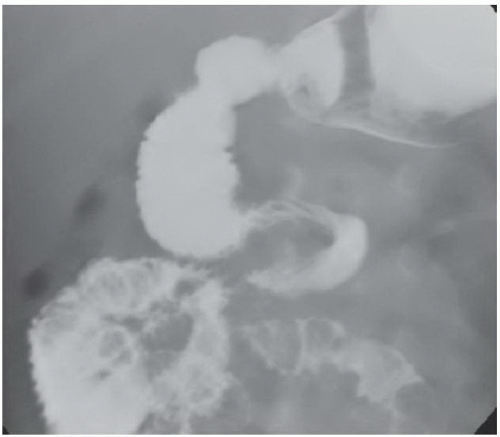

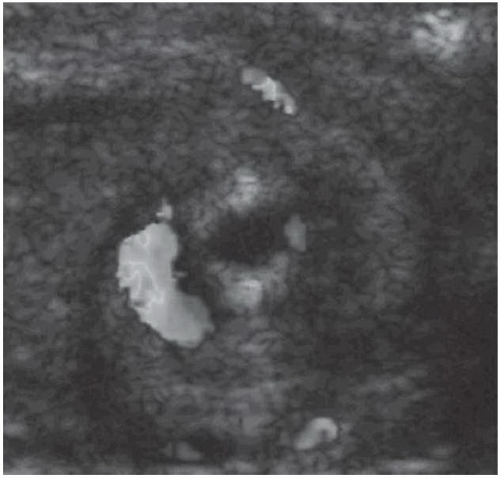

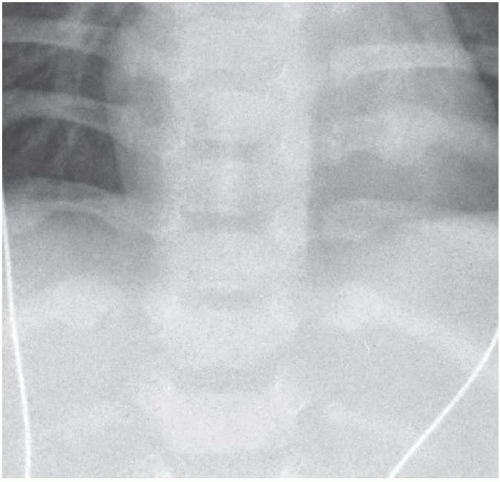

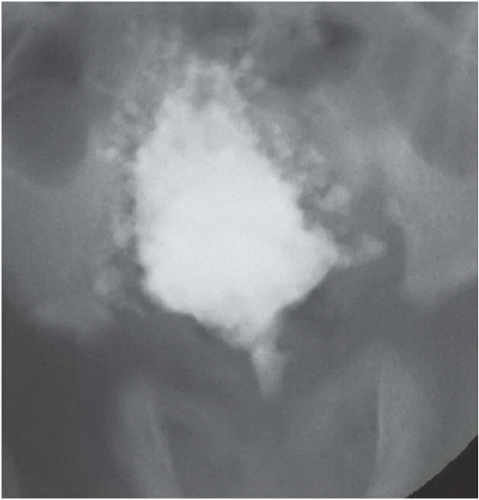

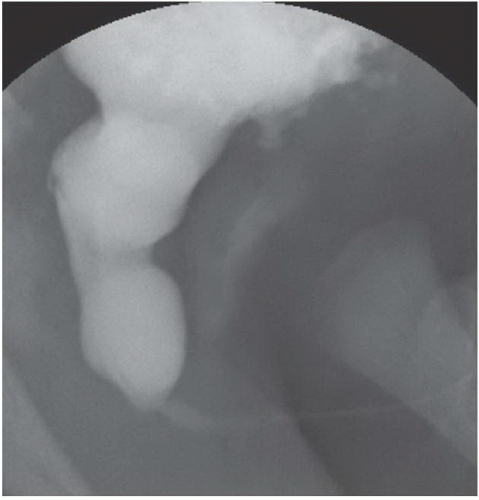

FINDINGS: Anteroposterior (AP; Fig. 1.1.1) and lateral (Fig. 1.1.2) views from an upper gastrointestinal series reveal partial duodenal obstruction, abnormal position of duodenal-jejunal junction (DJJ), and proximal small bowel in the right abdomen. A spiral or corkscrew configuration of the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum is also seen (Fig. 1.1.3). A sonographic image (Fig. 1.1.4) of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and vein (SMV) at the base of the small-bowel mesentery reveals a “whirlpool” pattern in which the SMV swirls around the SMA in a clockwise pattern.

DIAGNOSIS: Malrotation with midgut volvulus

DISCUSSION: Midgut malrotation complicated by midgut volvulus presents most frequently in the first month of life and is a true pediatric surgical emergency because of potential bowel ischemia and infarction. As plain films are unreliable for diagnosis or exclusion of midgut volvulus, an emergent upper gastrointestinal series with barium or nonionic water-soluble contrast medium is indicated to diagnose the duodenal obstruction and the abnormally positioned duodenal-jejunal junction (i.e., DJJ should be to the left of the spine and at the level of the bulb). The diagnosis of midgut volvulus may be made on ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) by identifying the characteristic “whirlpool sign” of the SMV wrapping around the SMA in a clockwise fashion. A Ladd’s operation is performed to diagnose and reduce the volvulus, resect any dead bowel, and lyse dense, aberrant peritoneal bands, also known as Ladd’s bands (1,2).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Bilious vomiting in a newborn is malrotation with midgut volvulus until proven otherwise.

Check for abnormal position and appearance of the DJJ and proximal small bowel on upper gastrointestinal series, which is the gold standard for diagnosis.

“Whirlpool sign” of twisted mesenteric vessels on sonography or CT indicates a midgut volvulus.

Case 1.2

HISTORY: Newborn with bilious vomiting, Down syndrome, and maternal polyhydramnios

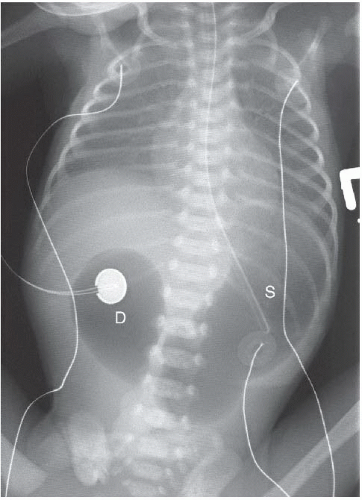

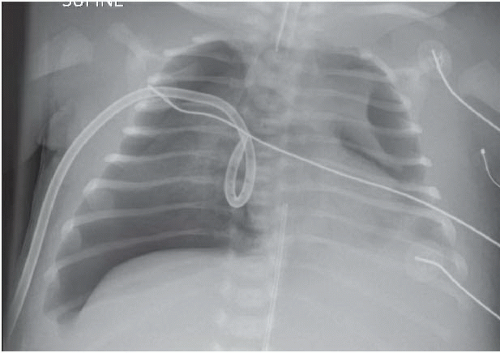

FINDINGS: The anteroposterior supine view of the chest and abdomen (Fig. 1.2.1) demonstrates a classic “double-bubble” sign: gaseous distention of the stomach (S) and an enlarged duodenal bulb or mega bulb (D). No intestinal gas is seen distal to the duodenum.

DIAGNOSIS: Duodenal atresia

DISCUSSION: Duodenal atresia is complete congenital intrinsic obstruction of the duodenum and is thought to result from failed recanalization. Approximately 30% of affected infants have Down syndrome (i.e., trisomy 21), 40% have maternal polyhydramnios, and 50% have some type of associated anomaly. Plain-film demonstration of the double-bubble sign is diagnostic and may be aided by injection of air through a nasogastric tube, as in the case presented. Upper gastrointestinal series is not indicated unless distal gas is present (i.e., partial duodenal obstruction exists). Distal gas requires further investigation for other etiologies of neonatal duodenal obstruction, such as duodenal stenosis or web, malrotation with Ladd’s bands or volvulus, annular pancreas, or duplication cyst (3).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

A double-bubble sign without distal bowel gas is diagnostic of duodenal atresia.

Case 1.3

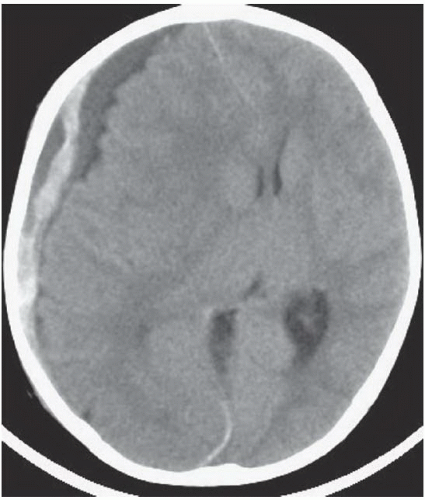

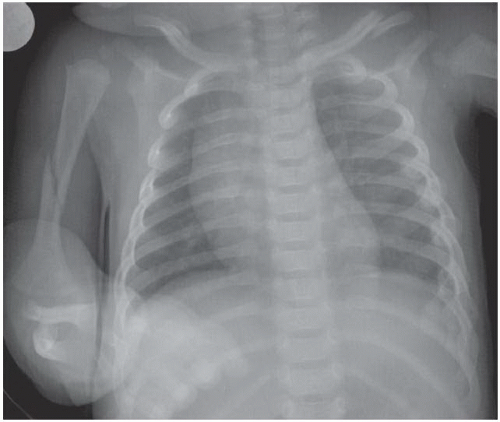

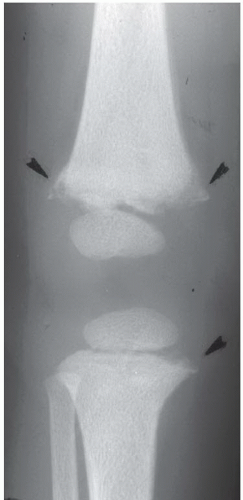

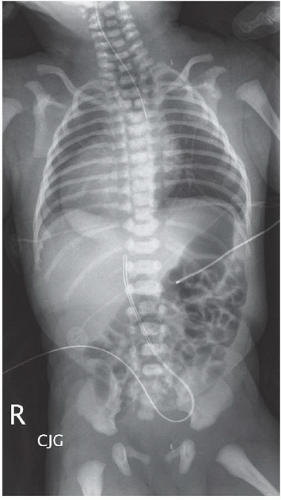

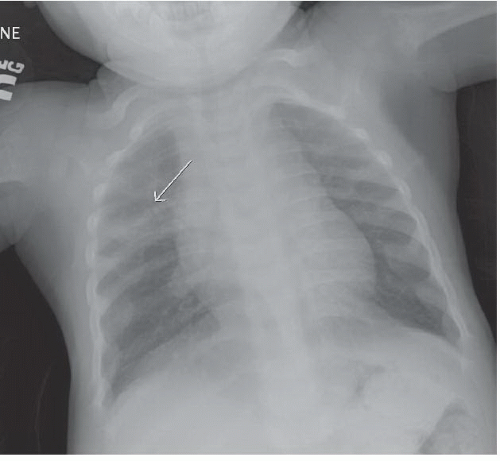

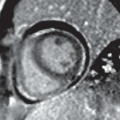

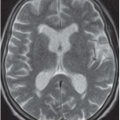

HISTORY: A 3-month-old infant with altered mental status

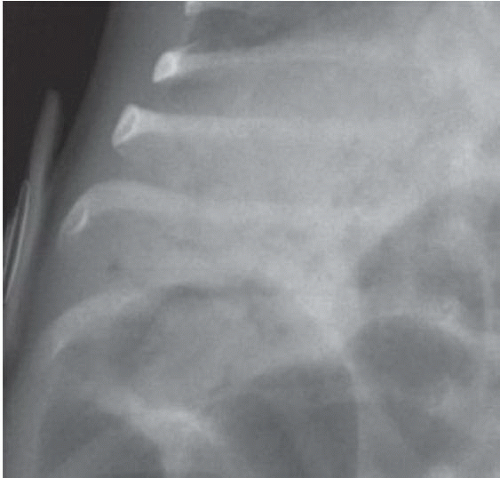

FINDINGS: An unenhanced axial CT reveals a right mixed-density subdural hematoma consistent with blood of varying ages (Fig. 1.3.1). The AP view of the chest reveals an acute spiral fracture of the right humerus, subacute fractures of the clavicles, and multiple healing rib fractures on the left (Fig. 1.3.2). Images from a skeletal survey reveal classic metaphyseal “corner” fractures of the medial proximal tibia (Fig. 1.3.3, arrowheads) as well as a “bucket-handle” fracture of the distal femoral metaphysis (Fig. 1.3.3, arrowheads). A coned down view of a follow-up chest x-ray (Fig. 1.3.4) obtained 2 weeks later reveals multiple healing posterior rib fractures that were not evident on the initial examination.

DIAGNOSIS: Non-accidental trauma

DISCUSSION: The classic metaphyseal corner and bucket-handle fractures are considered virtually pathognomonic of nonaccidental trauma (NAT) and result from indirectly applied shearing forces during shaking. These fractures are often subtle, and the case presented reinforces the importance of following suspicious areas on skeletal surveys with dedicated high-quality radiographs. On follow-up chest film (Fig. 1.3.4), multiple healing posterior rib fractures were identified in addition to the lateral fractures on the initial survey. Fractures of the posterior ribs at the junction of the transverse process of the vertebral body with the rib are highly specific for child abuse. It is thought that the forces generated by squeezing the chest of an infant while shaking are transferred along the course of the ribs, producing fractures in their lateral and posterior aspects. Shaken infants commonly present with seizures, lethargy, coma, retinal hemorrhages on funduscopic exam, and subdural hematomas caused by rupture of bridging veins from the cerebral cortex. All potentially abused infants with neurologic signs or symptoms should undergo an unenhanced CT of the brain (4,5).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Metaphyseal corner and bucket-handle fractures are virtually pathognomonic of nonaccidental trauma.

Fractures of the posterior ribs at the junction of the transverse process of the adjacent vertebral body with the rib are virtually pathognomonic of nonaccidental trauma.

Case 1.4

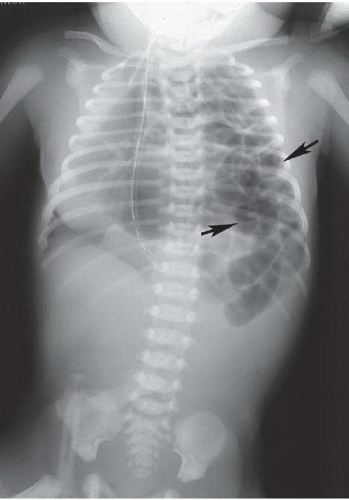

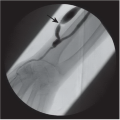

HISTORY: Newborn male infant with bilateral hydronephrosis detected in utero

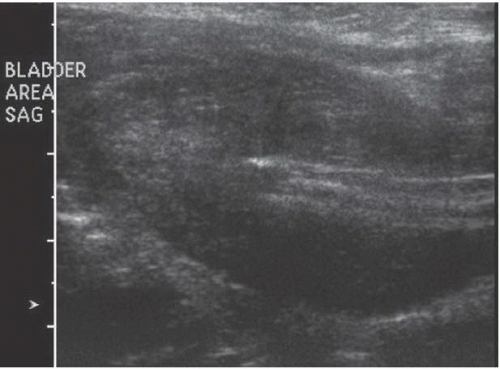

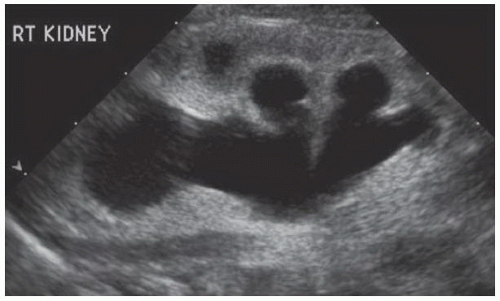

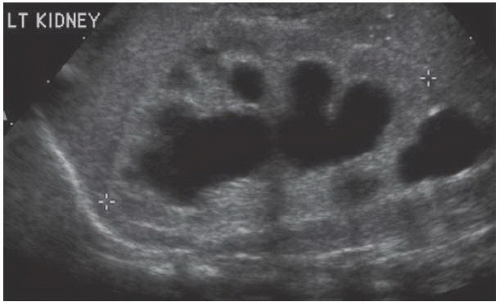

FINDINGS: Images during a voiding cystourethrogram demonstrate a thick-walled trabeculated bladder during filling (Fig. 1.4.1) and a bullet-nosed dilation of the posterior urethra (Fig. 1.4.2) with voiding. Shortly after birth, the patient had bilateral pneumothoraces and pulmonary hypoplasia (Fig. 1.4.3). Ultrasound examination reveals a markedly thickened bladder wall with a central catheter in place (Fig. 1.4.4) and bilateral hydronephrosis (Figs. 1.4.5 and 1.4.6) with loss of normal corticomedullary differentiation and cortical cysts.

DIAGNOSIS: Posterior urethral valves

DISCUSSION: Posterior urethral valves are the most common cause of bilateral hydronephrosis in a male infant. Affected infants may present with pulmonary hypoplasia and cystic renal dysplasia and a history of maternal oligohydramnios. Vesicoureteral reflux may be unilateral or bilateral and may lead to forniceal rupture, urinoma, and/or urinary ascites. Older children or adolescents may present with urinary tract infections, voiding difficulty, or end-stage renal disease. Type I valves are the most common and extend from the verumontanum distally, leaving a small eccentric opening posteriorly (Fig. 1.4.2) for the passage of urine. A voiding cystourethrogram is the test of choice for diagnosis. Treatment frequently involves early urinary diversion and subsequent valve ablation (6).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Bullet-nosed dilatation of the posterior urethra and bilateral hydronephrosis in a male infant = posterior urethral valves.

Case 1.5

HISTORY: A 1-year-old child with an abdominal mass, focal swelling of the right temple, anemia, and elevated urinary catecholamines

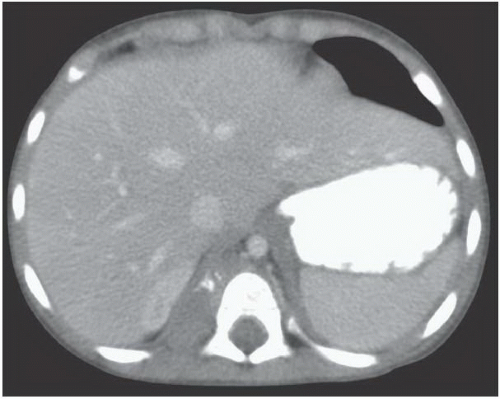

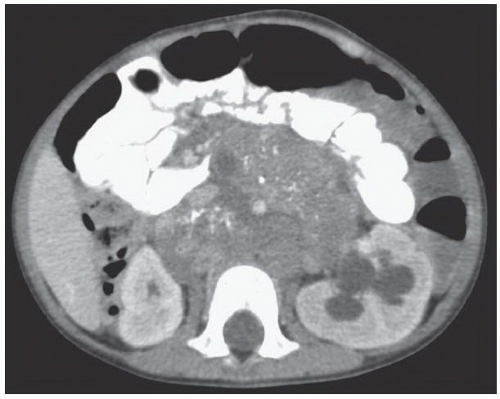

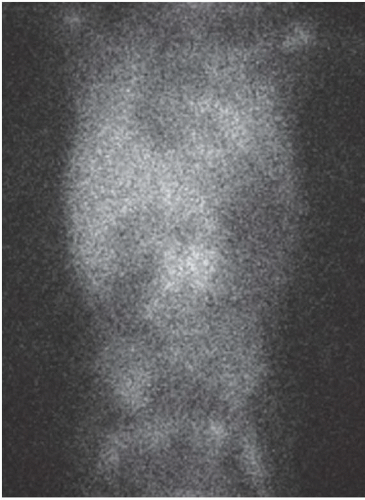

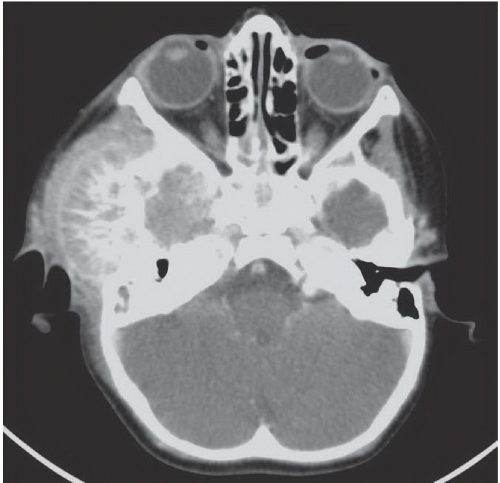

FINDINGS: IV contrast-enhanced CT images (Figs. 1.5.1 and 1.5.2) through the abdomen demonstrate a calcified right paraspinal mass; a large calcified retroperitoneal mass that crosses the midline, encasing the aorta and SMA; and left hydronephrosis. A delayed image from an metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan (Fig. 1.5.3) demonstrates increased uptake in the midabdomen corresponding to the retroperitoneal mass on CT. Head CT with IV contrast (Fig. 1.5.4) reveals a soft-tissue mass, with an epicenter in the right temporal bone, associated with bone destruction and a sunburst periosteal reaction.

DIAGNOSIS: Retroperitoneal neuroblastoma with skull metastases

DISCUSSION: Neuroblastoma is the most common solid extra-cranial malignant tumor of childhood. It is derived from primitive neural crest cells and, therefore, originates in the sympathetic chain ganglia and adrenal medulla. Two-thirds of cases arise in the abdomen, and two-thirds of abdominal tumors arise in the adrenal medulla. The most common sites of origin are adrenal medulla (35%), extraadrenal retroperitoneum (30%-35%), and posterior mediastinum (20%). Tumors in the neck and pelvis (3%-8%) are much less common. Peak age of presentation is 22 months. At diagnosis, 60% to 70% of patients have metastatic disease with spread to cortical bone (in particular the skull), bone marrow, liver, and lymph nodes. The main challenge in imaging these tumors is differentiating neuroblastoma from Wilms tumor. Calcification, suprarenal location with a displaced but normal ipsilateral kidney, vessel encasement, retrocrural adenopathy, and extension across the midline are features that allow a confident diagnosis of neuroblastoma. Paraspinal tumor may invade the spinal canal via extension through adjacent neural foramina and is best evaluated with CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although initial diagnosis is suspected when a calcified adrenal or paraspinal mass is identified on plain films and ultrasonography, CT of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, bone scans, MIBG scans, ± MRI are required for complete staging. MIBG (labeled with iodine-123) scintigraphy is sensitive and specific for catecholamine-secreting tumors; however, only 70% of neuroblastomas are MIBG-positive; therefore, normal results of MIBG do not exclude the diagnosis of neuroblastoma. Age and stage at diagnosis, N-myc oncogene amplification, DNA content, and Shimada histology are important prognostically and are used to stratify patients into high-, intermediate-, and low-risk groups. Treatment consists of chemotherapy and surgical debulking. Despite continued advancements in therapy, the prognosis remains poor (7).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

A childhood suprarenal mass with calcification that crosses the midline and encases the mesenteric vasculature and/or invades the neural foramina is almost certainly a neuroblastoma.

Case 1.6

HISTORY: Newborn with respiratory distress during feedings and failure to pass a nasogastric tube

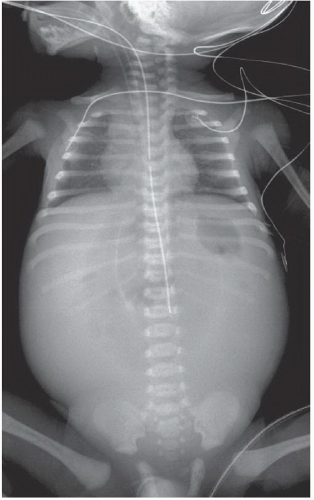

FINDINGS: Anteroposterior supine “babygram” (Fig. 1.6.1) reveals that the nasogastric tube terminates in a gas-filled proximal esophageal pouch. Bowel gas is present in the abdomen. The cardiac apex is in the right chest consistent with dextrocardia, and there are vertebral anomalies in the upper thoracic and sacral spine.

DIAGNOSIS: Esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula and vertebral and cardiac anomalies (VATER association)

DISCUSSION: The VATER association includes vertebral and cardiovascular anomalies, anorectal malformations, tracheoesophageal fistula, and renal and radial ray anomalies. The most common type of tracheoesophageal fistula is proximal esophageal atresia with a distal tracheoesophageal fistula, which is diagnosed on the basis of plain-radiographs demonstrating a feeding tube coiled in the proximal pouch with gas present distally. A barium “pouchogram” is not indicated, but the esophageal pouch can be made more conspicuous by injecting air through the nasogastric tube. Echocardiography and renal sonography are indicated to screen for congenital heart disease and renal anomalies, most commonly patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, and renal agenesis. Complications of esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula include aspiration pneumonia, postoperative leak and stricture, recurrent fistula, disordered esophageal motility, gastroesophageal reflux, congenital esophageal stenosis, and tracheomalacia (8).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

In the proper clinical setting, esophageal atresia is diagnosed by failure to pass a nasogastric tube and visualization of an air-containing proximal esophageal pouch.

Always look for the VATER association in patients with esophageal atresia.

Case 1.7

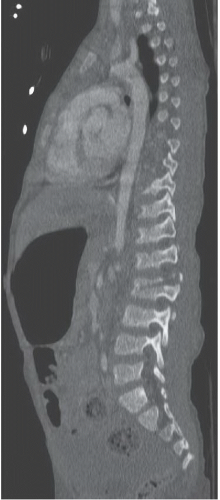

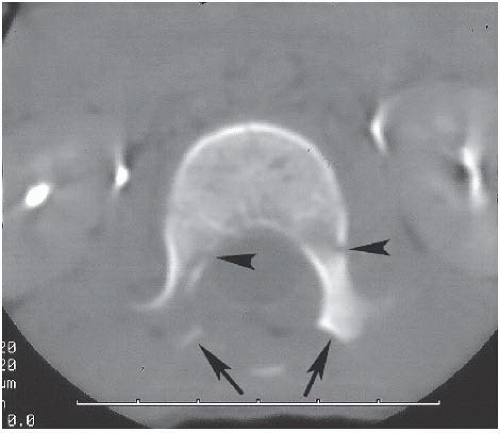

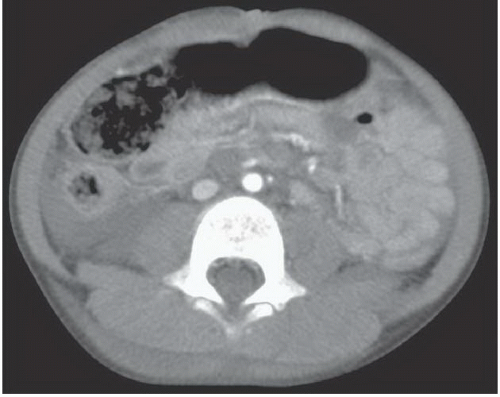

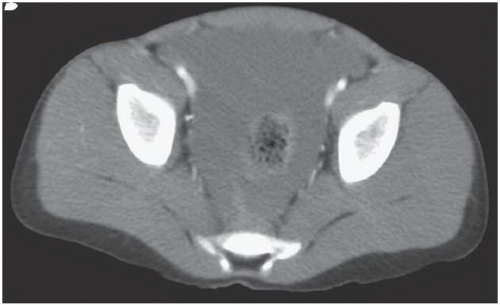

HISTORY: A 5-year-old child with a lap belt ecchymosis after a motor vehicle accident

FINDINGS: A transverse fracture through the body and posterior elements as well as distraction and separation of the posterior elements of L2 vertebra without anterior compression are seen on a lateral reconstructed CT image of the thoracolumbar spine (Fig. 1.7.1). Axial CT of L2 (Fig. 1.7.2) demonstrates the “naked facet” sign or lack of opposing facets at L2 (arrows) and bilateral pedicle fractures (arrowheads). Contrast-enhanced abdominal and pelvic CT reveals bowel-wall thickening and retroperitoneal fluid (Fig. 1.7.3) as well as extensive free intraperitoneal fluid in the pelvis (Fig. 1.7.4).

DIAGNOSIS: Lap belt injury complex (lap belt ecchymosis, distraction fracture of the lumbar spine, and bowel injury)

DISCUSSION: In a sudden-deceleration accident, hyperflexion around the axis of a lap belt disrupts the posterior spinal ligaments and distracts the posterior elements, resulting in the “naked facet” sign. The anterior vertebral body is not compressed, but a horizontal fracture through the vertebral body (i.e., Chance fracture) may also occur as in this case. Injuries to bowel and abdominal viscera may dominate the clinical picture, and the unstable spine injury may be overlooked without lateral radiography. Manifestations of bowel injury on CT scans include bowel-wall enhancement, bowel-wall thickening, free fluid, free air, and extraluminal oral contrast. In this clinical setting, unexplained intraperitoneal fluid on CT is a bowel injury until proven otherwise (9).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Lap belt injury complex = lap belt ecchymosis, distraction fracture of the lumbar spine, and bowel injury.

Case 1.8

HISTORY: Newborn infant with acute decompensation

FINDINGS: Frontal supine radiograph of the chest and abdomen (Fig. 1.8.1) reveals a large oval-shaped lucency overlying the epigastrium. There is a vertical soft-tissue density running through the lucency.

DIAGNOSIS: Pneumoperitoneum

DISCUSSION: A large amount of free intraperitoneal gas on a supine radiograph of the abdomen is manifested by an oval radiolucency in the epigastrium, reminiscent of an American football. The reflections of the parietal peritoneum demarcate the edges of the football. As air rises to the most anterior portion of the abdominal cavity, it surrounds the falciform ligament and may form a vertical line within the lucency in the upper abdomen. Similarly, the median umbilical fold containing the urachal remnant and the medial and lateral umbilical folds containing the umbilical arteries and inferior epigastric vessels, respectively, may produce additional caudal vertical lines. Although these vertical lines were not included in the original description, other authors have described them as the “laces” or “seams” of the football and thus, an integral part of the “football sign.” Typically, the football sign is seen in neonates and infants. The most common cause is spontaneous or iatrogenic gastric perforation, although it may be the consequence of a congenital bowel obstruction or necrotizing enterocolitis (10).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

The football sign, seen on a supine abdominal radiograph, is indicative of a massive pneumoperitoneum.

Case 1.9

HISTORY: A 6-month-old with fever, stridor, and dysphagia

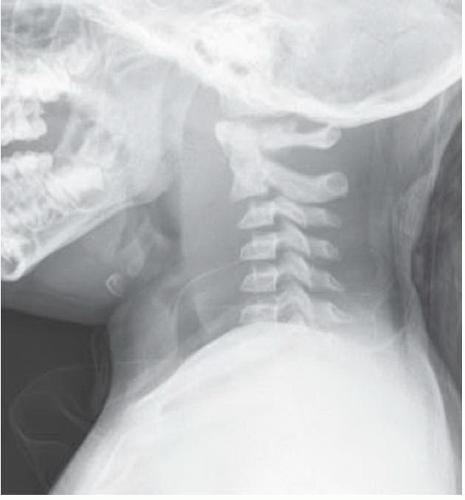

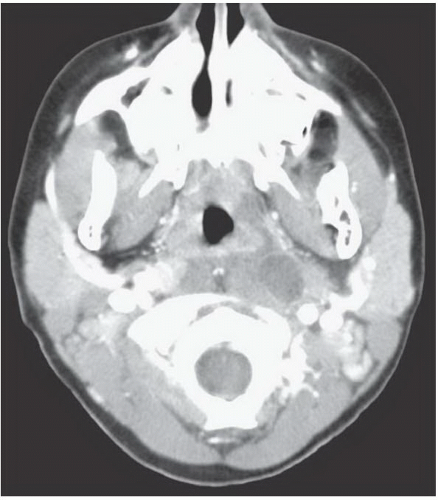

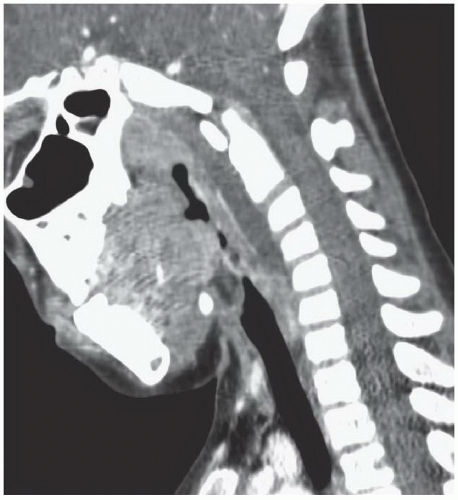

FINDINGS: Lateral radiograph of the neck reveals marked thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues with a convex anterior border (Fig. 1.9.1). Contrast-enhanced axial CT of the neck reveals a low-density, rim-enhancing region in the left lateral retropharyngeal soft tissues (Fig. 1.9.2) and a low-density region in the retropharyngeal soft tissues on the sagittal reconstruction (Fig. 1.9.3).

DIAGNOSIS: Retropharyngeal abscess and cellulitis

DISCUSSION: Typically, a retropharyngeal abscess is the sequela of a recent upper respiratory infection, most commonly Staphylococcus aureus or Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus. Less commonly, it may be caused by a foreign body. On lateral views of the neck, there is thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues and reversal of the normal cervical lordosis. The presence of gas in those tissues is diagnostic of an abscess; however, this is infrequent. The thickness of the soft tissues between the anterior edge of the cervical spine and the posterior aspect of the aerated pharynx should be no more than the AP diameter of the cervical vertebral bodies. Unfortunately, expiration and lack of extension can produce the appearance of thickening of the retropharyngeal soft tissues. Although repeat radiographs in full extension and inspiration can be helpful in differentiating true thickening from “pseudo-thickening,” fluoroscopy of the lateral neck definitively clarifies the difficult cases as pathologic soft-tissue thickening will persist throughout the respiratory cycle, and in all patient positions; however, pseudo-thickening will not. CT is used to differentiate cellulitis, characterized by soft-tissue swelling, from an abscess, characterized by a discrete, focal fluid collection with rim enhancement. CT also defines the extent of disease and involvement of adjacent structures, such as the airway and mediastinum, and enables localization of a fluid collection for subsequent drainage (11).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Retropharyngeal soft tissues should be no thicker than the AP diameter of the cervical vertebral bodies.

Retropharyngeal soft-tissue thickening with gas is pathognomonic of a retropharyngeal abscess.

Fluoroscopy may be useful in differentiating true thickening from “pseudo-thickening” of the retropharyngeal soft tissues.

Case 1.10

HISTORY: A 32-week-old, 1,500 g premature infant with abdominal distension, increased gastric residuals, and thrombocytopenia on day 6 of life

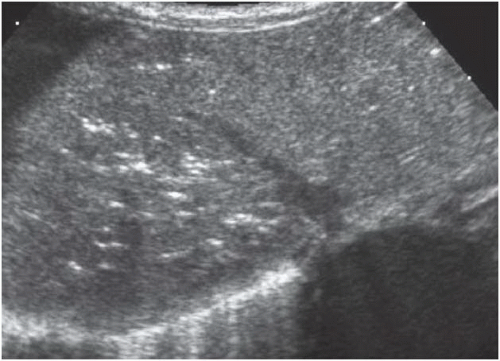

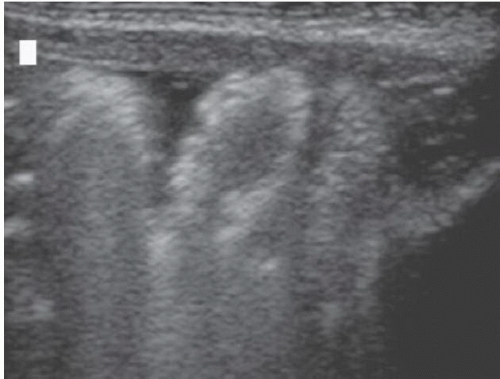

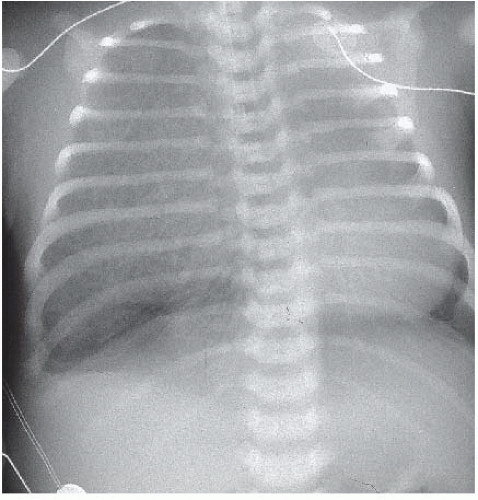

FINDINGS: Anteroposterior supine film of the abdomen (Fig. 1.10.1) demonstrates diffuse gaseous distention of bowel, linear and crescentic areas of pneumatosis intestinalis (Fig. 1.10.2), and branching lucencies of portal venous gas (Fig. 1.10.3). Sonography of the liver (Fig. 1.10.4) reveals echogenic foci bubbling through the liver. Sonography of the abdomen reveals free fluid between bowel loops with echogenic walls (Fig. 1.10.5).

DIAGNOSIS: Necrotizing enterocolitis

DISCUSSION: Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) most frequently affects premature infants or full-term infants with congenital heart disease. The underlying pathophysiology is multifactorial, but the mucosal injury probably results from ischemia compounded by hyperosmolar feedings and infection. The earliest radiographic signs are nonspecific dilatation and separation of loops. Pneumatosis and portal venous gas indicating severe disease appear subsequently. Submucosal air demonstrates a bubbly appearance. Subserosal pneumatosis manifests as crescentic rings and linear lucencies paralleling the bowel lumen. Sonographically, one may see thick-walled fluid-filled aperistaltic loops. Pneumatosis demonstrates intense intramural echoes with acoustic shadowing. Punctate echogenicities moving through the portal vein and its branches in the direction of blood flow are characteristic of portal venous gas. Pneumoperitoneum, ascites, or both signal perforation and the need for surgical intervention. The mortality rate in children with NEC approaches 40%. Colonic strictures, typically in the left colon, are a common late complication in survivors (12,13).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Necrotizing enterocolitis occurs in premature infants or full-term infants with congenital heart disease.

Plain-film findings of NEC are dilated bowel loops, pneumatosis, and portal venous gas.

Pneumoperitoneum, ascites, or both indicate bowel perforation and the need for immediate surgery.

Case 1.11

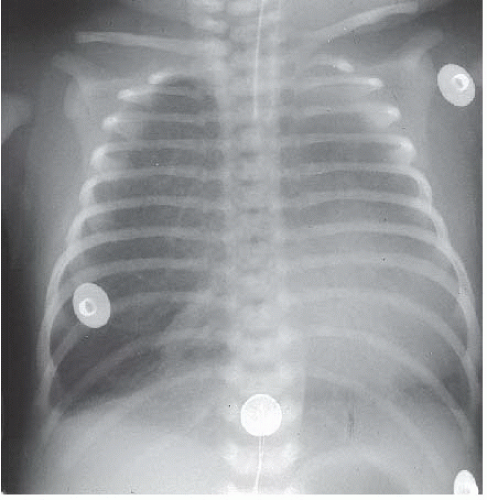

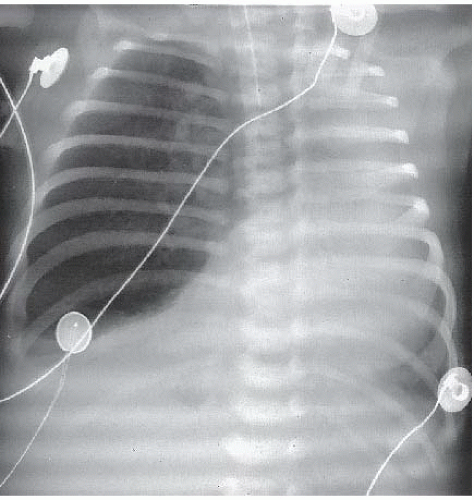

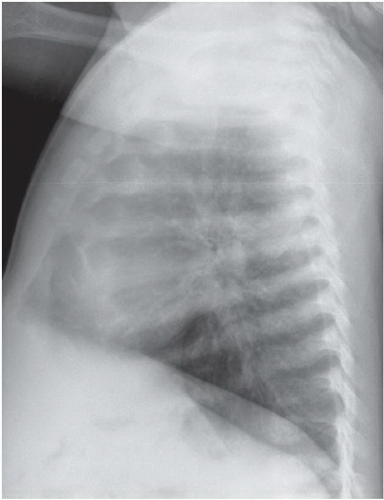

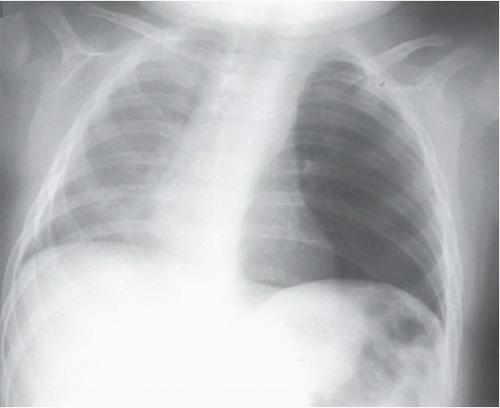

HISTORY: Full-term infant with progressive respiratory distress

FINDINGS: A series of chest films obtained from day 1 to day 4 of life demonstrate initial opacification of the right upper lobe (Fig. 1.11.1), which subsequently becomes interstitial or reticular (Fig. 1.11.2) and finally hyperlucent (Fig. 1.11.3). Right-to-left mediastinal shift and progressive right middle and lower lobe collapse are also identified.

DIAGNOSIS: Congenital lobar emphysema of right upper lobe

DISCUSSION: Mediastinal shift is the hallmark of “surgical” causes of neonatal respiratory distress. The etiology of congenital lobar emphysema remains unclear. In most cases, congenital lobar emphysema is associated with an intrinsic ball-valve obstruction in the affected bronchus. The result is progressive air trapping with mediastinal shift and compressive atelectasis of adjacent lobes. The initial opacification of the affected lobe results from impaired drainage of fetal lung fluid. The upper lobes and the right middle lobe are most frequently affected. Differentiation of congenital lobar emphysema from other surgical lesions of the lung in newborns (sequestration and cystic adenomatoid malformation) requires recognition of the characteristic location and temporal evolution of this abnormality. Infants with severe respiratory distress are treated by lobectomy, whereas functional assessment with ventilation-perfusion scanning and nonsurgical management may be indicated in less severely affected infants (14).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Progressive air trapping in the middle or either upper lobe in a newborn = congenital lobar emphysema.

Although it will become hyperlucent within days, the affected lobe may initially be opacified owing to retained fetal lung fluid.

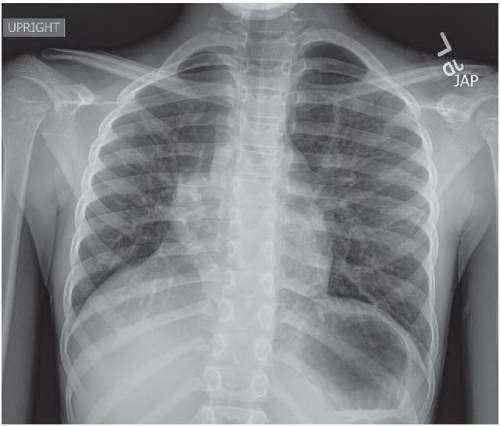

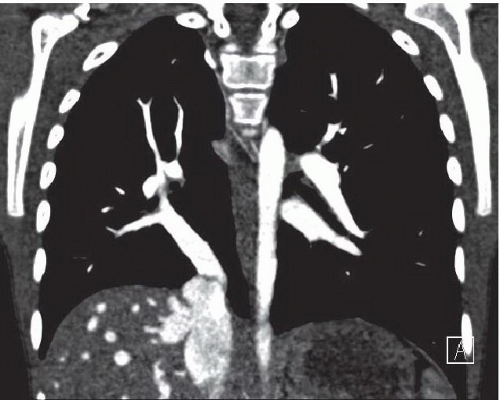

Case 1.12

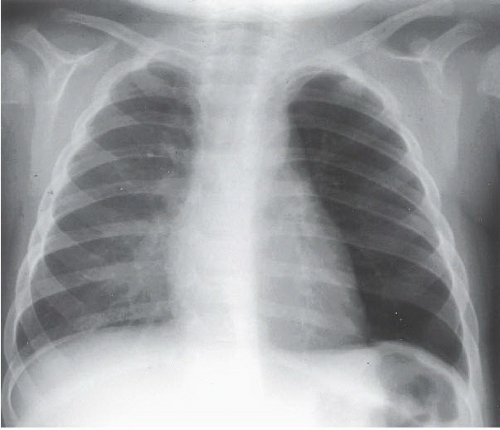

HISTORY: An 8-year-old female with history of recurrent right lung pneumonias that does not ever clear completely.

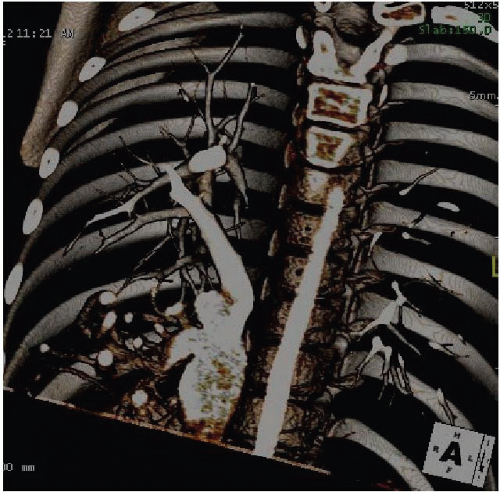

FINDINGS: Frontal radiograph of the chest (Fig. 1.12.1) reveals the heart to be shifted to the right, the right hemidiaphragm to be elevated, and the right heart border to be indistinct. There is a linear density pointing inferomedially in the right hemithorax to the medial right hemidiaphragm. Coronal (Fig. 1.12.2) and 3D reconstructions of chest CT with IV contrast (Fig. 1.12.3) reveal a large vessel draining the right pulmonary veins into the inferior vena cava (IVC) just below the hemidiaphragm.

DIAGNOSIS: Scimitar syndrome

DISCUSSION: Scimitar, or congenital venolobar, syndrome is a rare congenital anomaly classically characterized by right-sided anomalous pulmonary venous return below the diaphragm, right pulmonary hypoplasia, and dextroposition of the heart secondary to shift of the heart and mediastinum toward the hypoplastic lung. The eponym “scimitar” refers to the shape of the anomalous pulmonary vein on the frontal chest radiograph, which is reminiscent of the curved Turkish scimitar sword. In the majority of the patients with scimitar syndrome, the unilateral anomalous pulmonary venous drainage is total, whereas in approximately one-third, the anomalous vein drains only the lower portion of the lung. Typically, the anomalous vein drains into the subdiaphragmatic IVC, as in this example, but may drain into an hepatic vein, low in the right atrium, or even the portal vein. Seldom has the scimitar vein been described in the left lung.

Presentation is highly variable but has a bimodal distribution in infancy and later pediatric or adult life. The incidence is 2 per 100,000, and females are more commonly affected (2:1) than males. The infant with scimitar syndrome may present with tachypnea, recurrent pneumonia, failure to thrive, or heart failure. The infantile form has a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality secondary to numerous associated reported cardiovascular abnormalities (75% incidence in neonates as opposed to 36% in the older pediatric age group). The following cardiovascular anomalies in addition to the scimitar vein in order of descending frequency have been commonly reported: hypoplasia of the right pulmonary artery, systemic arterial supply to the right lung from infradiaphragmatic aorta, and secundum atrial septal defect. Noncardiovascular anomalies include pulmonary sequestration, right-sided diaphragmatic hernia, and horseshoe lung. The older child or adult may be relatively asymptomatic and the diagnosis made incidentally, have milder pulmonary symptoms or, as in this case, have a history of recurrent pneumonias.

Diagnosis is typically made by the characteristic plain-film findings. In cases with marked dextroposition of the heart, the scimitar vein, however, may be obscured or misinterpreted. CT is very helpful in delineating the anomalous venous drainage and other associated anomalies. In the symptomatic patients, cardiac catheterization is utilized to evaluate venous and arterial anatomy, potential areas of stenosis, and to measure pulmonary pressures.

For patients who are asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic, conservative medical management is appropriate. Patients with infantile scimitar syndrome, heart failure, or pulmonary hypertension may require surgical intervention, typically consisting of redirection of the scimitar vein to the left atrium. The presence of pulmonary hypertension may necessitate embolization or surgical ligation of anomalous systemic arteries, and, in the setting of recurrent pulmonary infections, resection of the affected portions of the right lung (15,16).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Scimitar syndrome is characterized by anomalous right pulmonary venous drainage (the scimitar vein), right pulmonary hypoplasia, and dextroposition of the heart.

The sine qua non of scimitar syndrome is the scimitar vein, which passes from superolateral position to inferomedial position in the right chest.

In general, the prognosis of the infantile form of scimitar syndrome is much poorer than that of patients who present in later childhood or even adulthood because of the increased incidence and severity of associated anomalies in the infantile form.

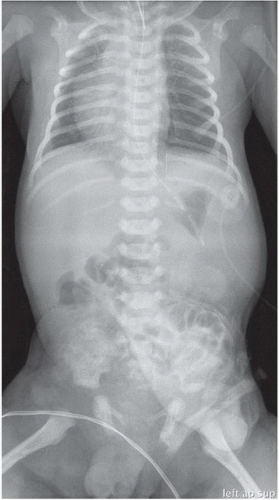

Case 1.13

HISTORY: Full-term neonate with the classic obstructive triad of bilious vomiting, abdominal distention, and failure to pass meconium.

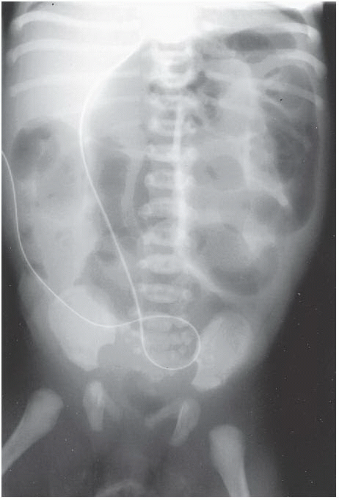

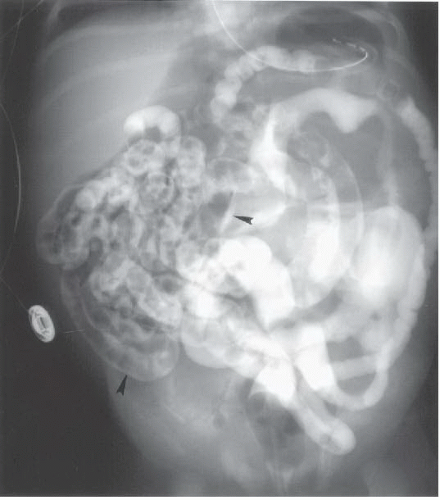

FINDINGS: Anteroposterior supine (Fig. 1.13.1) view of the abdomen demonstrates numerous dilated loops of bowel. A contrast enema (Fig. 1.13.2) reveals a microcolon and numerous filling defects in the ileum (arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Meconium ileus

DISCUSSION: Meconium ileus is the neonatal presentation of cystic fibrosis. Hydramnios and a family history of cystic fibrosis may be present. With simple meconium ileus, abnormally viscid meconium obstructs the ileum, and a water-soluble contrast enema with ileal reflux to the level of the dilated loops can relieve the impaction. This disorder is said to produce the smallest of all microcolons because the obstructing meconium causes the colon to be completely unused. In nearly half of cases, meconium ileus may be complicated by volvulus, atresia, stenosis, perforation, peritonitis, or pseudocyst formation. Complicated meconium ileus may present early, and severe abdominal distension and respiratory distress may require corrective surgery (17). A similar diagnosis may be made in older children with cystic fibrosis where viscid stool obstructs the ileum and cecum. This disorder is known as meconium ileus equivalent.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Meconium ileus is diagnostic of cystic fibrosis.

Meconium ileus produces the smallest of all microcolons.

A water-soluble contrast enema is diagnostic and therapeutic in uncomplicated cases.

Case 1.14

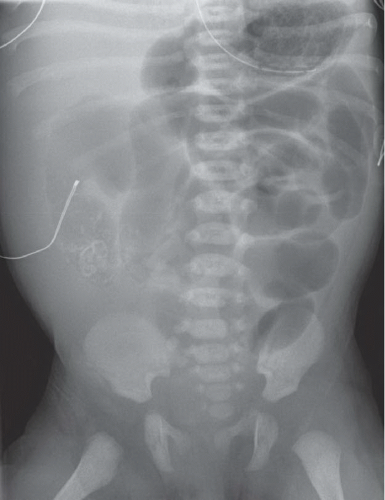

HISTORY: Newborn with abdominal distension

FINDINGS: AP supine radiograph of the abdomen (Fig. 1.14.1) reveals a collection of calcifications in the right lower quadrant and multiple dilated air-filled loops of bowel without definite gas in rectum, consistent with a distal bowel obstruction.

DIAGNOSIS: Meconium peritonitis

DISCUSSION: Meconium peritonitis is the result of in utero perforation and prenatal leak of meconium into the peritoneal cavity. The underlying etiology varies but includes obstruction or malformation, although obstructive lesions are identified in only 50% of the cases. Meconium peritonitis usually results in intraperitoneal calcification that may be focal or scattered, diffuse or punctuate, or may outline the walls of a pseudocyst, which contains meconium. Additional findings vary with the underlying cause but include bowel obstruction, mass, or distension. Sonographically, meconium peritonitis may be diagnosed prenatally or postnatally by the presence of focal or scattered areas of hyperechogenicity consistent with calcifications or of a cystic mass containing echogenic meconium with hyperechoic rim. Treatment and prognosis depend on the etiology. Calcification will gradually disappear over months or years (18).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Scattered or focal, punctuate peritoneal calcifications or a calcified pseudocyst in a newborn = shape in utero bowel perforation and meconium peritonitis.

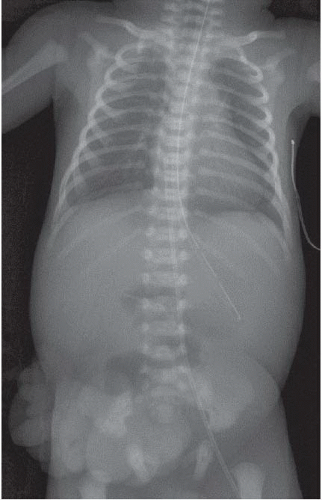

Case 1.15

HISTORY: A 1-year-old immigrant child with growth failure

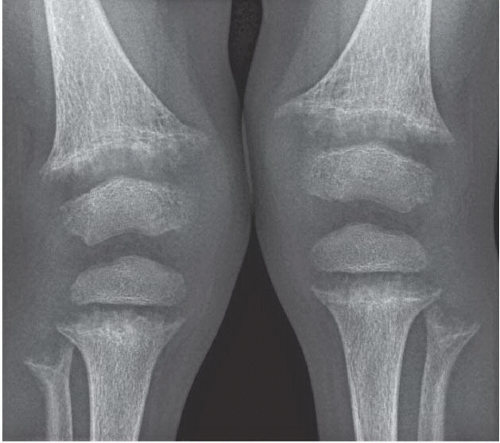

FINDINGS: Metaphyseal cupping, fraying, and splaying are demonstrated on AP views of the wrist (Fig. 1.15.1) and knees (Fig. 1.15.2). Also apparent is loss of the zone of provisional calcification—seen radiographically as widening of the physes and loss of the epiphyseal and metaphyseal margins. The visualized skeleton shows diffuse coarse demineralization. AP (Fig. 1.15.3) and lateral (Fig. 1.15.4) views of the chest reveal cupping and fraying of the costochondral junctions and proximal humeral metaphyses.

DIAGNOSIS: Rickets

DISCUSSION: Deficient mineralization of osteoid in children is known as rickets, whereas in adults the same pathologic process is osteomalacia. Many types and causes of rickets result in this classic Aunt Minnie appearance. Rachitic changes on radiographs reflect a relative or absolute deficiency of vitamin D or its hormonally active derivative 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. Remembering that the biosynthetic pathway of vitamin D involves skin, gut, liver, and kidney assists formulation of a basic differential diagnosis. Other pathologic processes in the gut or kidneys that result in calcium or phosphorus wasting can also result in rickets.

Because rachitic changes are best visualized at the ends of the most rapidly growing bones, a rickets survey routinely includes views of the wrists and knees. In addition to the metaphyseal cupping and fraying and loss of the zone of provisional calcification producing widened physes, long bones may demonstrate bowing deformities as well. Cupping and fraying of the costochondral junctions, which are metaphyseal equivalents, create palpable masses on the anterior chest wall likened to the beads of a rosary. Rickets is seldom encountered before 6 months of age in full-term infants, and most cases are diagnosed before the patient is 2 years old (19).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

In rickets, the metaphyses are cupped, frayed, and splayed.

Vitamin D deficiency causes poor osteoid mineralization and widening of the physes.

Case 1.16

HISTORY: Obese black male adolescent with pain in the right hip

FINDINGS: An AP view of the pelvis (Fig. 1.16.1) shows widening of the right proximal femoral physis, metaphyseal irregularity, and regional osteopenia. Lines drawn along the lateral femoral necks would intersect less femoral epiphysis on the right than on the left. The frog-leg lateral view (Fig. 1.16.2) reveals posterior and medial displacement of the epiphysis relative to the metaphysis, producing the classic appearance of “ice cream falling off the cone.”

DIAGNOSIS: Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

DISCUSSION: SCFE, a Salter-Harris type I fracture of the proximal growth plate of the femur, is usually encountered during the adolescent growth spurt. Black (male or female) and male (of any race) patients are most commonly affected. Children with SCFE are usually overweight and present with hip pain, limp, or referred knee pain. Younger and older presentations suggest hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, and prior radiotherapy. Both hips are affected in approximately 25% of patients.

Anteroposterior and frog-leg lateral radiographs of the hips should be obtained in suspected cases of SCFE. A line, also known as Klein’s line, drawn along the lateral edge of the femoral neck should bisect at least one-sixth of the femoral epiphysis on an AP view. If the line intersects less than this amount, SCFE should be suspected. As the primary direction of slippage is posterior and medial, the frog-leg lateral view may show the epiphyseal displacement to best advantage.

SCFE is a true orthopedic emergency, and the goal of treatment is to prevent further slippage by internal fixation. Complications of SCFE include avascular necrosis, chondrolysis, varus deformity with femoral neck shortening, and early degenerative osteoarthritis. The epiphysis is fixated in the position it is found in because attempts to reduce the epiphysis increase the risk of avascular necrosis (20).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

SCFE occurs most frequently in adolescent males, and 25% of cases are bilateral.

SCFE is an orthopedic emergency, and the epiphysis is pinned “as is” to prevent further slippage.

Case 1.17

HISTORY: A 1-year-old with acute onset of wheezing

FINDINGS: AP chest radiograph (Fig. 1.17.1) demonstrates slight increased lucency of the left hemithorax. A film obtained during expiration (Fig. 1.17.2) shows impressive left-to-right mediastinal shift and unilateral left-sided air trapping.

DIAGNOSIS: Foreign body (Palmetto bug) in the left main stem bronchus

DISCUSSION: Foreign bodies in the lower airway are a commonly encountered pediatric problem, particularly in children younger than 3 years. The child may present acutely with cough, respiratory distress, and wheezing or more insidiously with fever, cough, recurrent pneumonia, pneumomediastinum, or pneumothorax. Peanuts are the most common foreign body to be aspirated, and bronchial impaction occurs more frequently on the right than on the left. The affected lung may be collapsed, normally aerated, or emphysematous. Inspiratory views alone have a normal appearance in 20% of patients, necessitating an expiratory view of the chest or chest fluoroscopy. Decubitus views in the uncooperative child may replace inspiratory/expiratory views. In the presence of an obstructing foreign body, the dependent lung fails to collapse. Routine radiologic evaluation can still be normal in up to 30% of children with proven lower-airway foreign bodies, hence the need for bronchoscopy in any child with strong clinical suspicion and negative films. CT may reveal the presence and location of an aspirated foreign body when initial imaging studies and bronchoscopy are negative (21).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Foreign-body aspiration is most common in children younger than 3 years.

Unilateral air trapping during expiration is diagnostic in the appropriate clinical setting.

Chest fluoroscopy or decubitus views may be very useful in identifying air trapping in the uncooperative child.

Even in the absence of radiologic findings, bronchoscopy is recommended when there is a strong clinical suspicion of foreign-body aspiration.

Case 1.18

HISTORY: Newborn with severe respiratory distress

FINDINGS: AP chest and abdomen film (Fig. 1.18.1) shows marked left-to-right shift of the heart, mediastinum, and support apparatus. The left side of the chest contains multiple tubular radiolucencies (arrows), and the abdomen is gasless.

DIAGNOSIS: Congenital diaphragmatic hernia, Bochdalek type

DISCUSSION: Congenital Bochdalek-type diaphragmatic hernia is a common surgical cause of neonatal respiratory distress. Herniation of abdominal contents occurs through a posterolateral diaphragmatic defect or persistent pleuroperitoneal canal. It is convenient to remember that Bochdalek hernias occur in the back, are more common on the left than right, and are associated with a scaphoid, gasless abdomen. Intestinal malrotation is present in all cases. The degree of associated pulmonary hypoplasia and persistent fetal circulation from pulmonary hypertension determines prognosis and management. Delayed appearance of diaphragmatic hernias is often right-sided and may be idiopathic or may be associated with previous group B streptococcal pneumonia. Sonography is useful for both prenatal and postnatal diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia. On prenatal sonograms, the presence of the stomach bubble adjacent to the heart on a true transverse image should alert the radiologist to this diagnosis (22).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

The presence of bowel in the left chest in a newborn is diagnostic of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

Older infants with right-sided hernias often have a history of previous group B streptococcal pneumonia.

On a transverse obstetrical ultrasound image, look for the stomach bubble adjacent to the heart to suggest this diagnosis.

Case 1.19

HISTORY: One-hour-old newborn with abnormal prenatal ultrasound

FINDINGS: AP chest and abdomen radiograph (Fig. 1.19.1) reveals an endotracheal tube and enteric tube to be in appropriate position. The apex of the cardiothymic silhouette is on the right. The stomach is noted to be on the left. There is a soft-tissue mass overlying the mid abdomen with indistinct superior margins and sharply defined inferior and lateral margins. The mass appears to contain bowel gas. An umbilical clip is noted at the inferior extent of the mass. The bowel gas pattern is not distended, and there is no evidence of free intraperitoneal air.

DIAGNOSIS: Omphalocele

DISCUSSION: Omphalocele is a congenital ventral abdominal defect in which abdominal contents, primarily bowel and sometimes liver, are herniated outside the abdominal wall and are covered by a sac. The defect is in the midline and invariably the umbilical cord inserts into the omphalocele sac as this anomaly is the result of failure of bowel to return to the abdomen after its normal developmental herniation into the umbilical cord during gestation from 6th to 10th weeks . Although maternal serum alpha fetoprotein levels may be elevated, omphalocele is most commonly diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound. The incidence is 1 in 4,000 live births. There is a high association (50%-70%) of structural or chromosomal abnormalities, primarily trisomies. The most commonly associated structural abnormalities are cardiac (30%-50%) but other VATERL anomalies and the potentially life-threatening anomalies of the central nervous system—hydrancephaly and holoprosencephaly—have been reported. Omphaloceles may be small or gigantic, and they may occur in the setting of syndromes, the most common one being Beckwith Weideman syndrome, comprising macroglossia, organomegaly, and hypoglycemia in addition to the omphalocele. These patients are also at increased risk for Wilm’s, hepatoblastoma, and neuroblastoma in later childhood.

Surgical correction may be accomplished with primary (if small) or staged closure of the abdominal wall defect. Flaps, tissue expanders, and mesh patches have been utilized to achieve closure of the defect. The long-term outcome of the child with omphalocele is dependent on the type and severity of the associated anomalies (23,24).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Omphalocele is a midline ventral abdominal wall defect in which abdominal contents are herniated into the base of the umbilical cord.

Associated anomalies (both structural and chromosomal anomalies) are extremely common (50%-70%) and are the primary determinant of prognosis and outcome in patients with omphalocele.

Case 1.20

HISTORY: One-hour-old newborn with abnormal prenatal ultrasound

FINDINGS: AP chest and abdomen radiograph (Fig. 1.20.1) reveals an umbilical venous catheter with the tip overlying the right atrium and an enteric tube in the stomach. There is paucity of bowel gas in nondistended loops overlying the midabdomen. There is no evidence of free intraperitoneal air. There are well-circumscribed fingerlike masses overlying the right lower quadrant and pelvis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree