Pleural Disease

Chapters 3 and 4 concentrated on the wide variety of diseases that can affect the lung parenchyma and the diversity of the intrapulmonary shadowing that they cause. Many diseases also involve and invade the pleura but, when they do, the variety of radiographic shadowing that results is limited. This chapter describes the radiographic appearances that result from the presence of air (pneumothorax), fluid (pleural effusion), pus (empyema) and solid tumour within the pleural cavity. Combinations of these ‘fillings’ occur (e.g. hydropneumothorax and pyopneumothorax) and pleural fluid may be composed of transudate, exudate, blood and, rarely, chyle. There are also characteristic patterns of pleural calcification and these are discussed at the end of the chapter.

The management of pleural disease can be difficult. There are serious potential diagnostic pitfalls and accurate radiographic interpretation is paramount in avoiding these. Clinical management and radiographic diagnosis are intimately interwoven when dealing with pleural disease and this interplay provides much of the emphasis of this chapter. Please note the ‘Hazard’ icons, highlighting potential mistakes that can have severe clinical consequences.

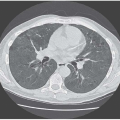

PNEUMOTHORAX (SEE FIG. 1.21, PAGE 16)

There is a little respiratory physiology to start with because it helps in understanding the management and prognosis of pneumothorax.

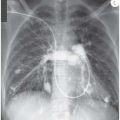

Intra-alveolar pressure is greater than intrapleural pressure. It follows that if an alveolus ruptures, air will pass into the pleural space until the pressure equalizes. The pressure changes that occur within the affected hemithorax result in depression of the hemidiaphragm and shift of the mediastinum to the opposite side. If the degree of mediastinal shift is sufficient to compromise the normal lung and/or the rise in intrapleural pressure sufficient to impair venous return to the right side of the heart (and therefore systemic cardiac output) the pneumothorax is said to be under ‘tension’. This is a medical emergency – the radiographic hallmark is significant mediastinal shift and the clinical hallmarks are tracheal deviation on palpation in the suprasternal notch and cardiovascular compromise.

Even relatively small pneumothoraces can result in tension, the reason probably being that the visceral pleura creates a flap over the leak and operates as a ball valve, allowing air to pass into the pleural space on inspiration but preventing its escape during expiration. A dramatic increase in intrapleural pressure can subsequently occur, sometimes with relatively small volume change. Always check clinically and radiographically for mediastinal shift.

Once the air leak seals and accumulation of the pneumothorax ceases, re-expansion will take place at a the rate of 1.25 per cent of the volume of the hemithorax per day. This natural reabsorption is speeded by administering oxygen.

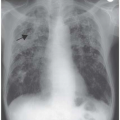

Pneumothoraces are either spontaneous or traumatic. Spontaneous pneumothoraces can be primary or secondary depending on the presence or absence of underlying lung disease. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax is a common condition, particularly in young men (the male:female ratio is 3:1). It results from rupture of a surface bleb towards the apex of the lung. Tall people are more prone to developing such blebs as the distance from the apex to the base of their lungs is greater and a more negative intrapleural pressure therefore exists at their lung apices.

A number of conditions predispose to secondary spontaneous pneumothorax. These include, commonly, emphysema and asthma, and also tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis and staphylococcal pneumonia (probably as a result of its propensity to cavitate). Uncommon pathologies that are complicated by recurrent pneumothoraces are histiocytosis X, pulmonary neurofibromatosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan’s syndromes and congenital lung cysts. The patients with eosinophilic granuloma and a congenital lung cyst depicted in Figs 4.41 and 4.42 respectively (pages 100 and 101) each suffered pneumothoraces, recurrent in the first case.

The physiological effects of a pneumothorax are exaggerated in the presence of underlying lung disease, as are the symptoms that the patient experiences. From a management point of view, it follows that the threshold for inserting an intercostal drain is lower in those with underlying lung disease.

A small primary spontaneous pneumothorax probably requires no treatment but the problem lies in the definition of ‘small’. Much research effort has been exerted in attempting to provide protocols for the management of pneumothorax, including the relative merits of pleural aspiration and pleural drainage. A detailed discussion is inappropriate here and I refer the reader to the British and American Thoracic Society guidelines. However, factors that do influence invasive management will be the degree of symptomatology and physiological derangement, the presence of underlying lung disease and, in my view, the length of the history (if a lung has been collapsed for a period of time its visceral pleura becomes thickened and less compliant to lung re-expansion).

Catamenial pneumothorax. This condition is associated with intrapleural endometriosis with fragments of endometrial tissue probably finding their way into the pleural space through diaphragmatic defects. The fact that such congenital defects are commoner in the right hemidiaphragm explains why almost all documented cases of catamenial pneumothorax have been right sided. At the onset of menstruation, the endometrial patch breaks down and a pneumothorax results. Consider this diagnostic possibility in a young woman with recurrent pneumothoraces – a history that reveals a connection with menstruation should clinch the diagnosis.

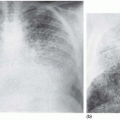

The radiographic appearances do not, of course, help in distinguishing the cause of a pneumothorax unless there is evidence of underlying lung disease. There is little difficulty in recognizing a classical pneumothorax with a rim of air surrounding a partially collapsed lung (see Fig. 1.21, page 16), but small leaks can be challenging as can atypical appearances, with localized or unusual accumulation of air, perhaps because of pre-existing pleural adhesions.

Before inserting a chest drain, be absolutely certain that any abnormal collection of air is in the pleural space – it is not ideal to insert a drain into a bulla or a lung cyst. If in any doubt, discuss further imaging.

PLEURAL EFFUSION

Table 5.1 lists causes of pleural effusion, categorized according to prevalence and on the basis of their being either a transudate or an exudate.

Table 5.1 Causes of pleural effusion | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||