Probably Benign Findings Appropriately Managed with Short-Interval Follow-up

One of the most controversial topics in mammography is the classification and management of a finding that is probably benign (1). These are lesions that are almost always benign but on rare occasion prove to be cancer. The probability of cancer is <2% to 5%, but not zero. Many physicians believe that, based on cost and benefit, these lesions do not require biopsy but can be followed, and, if they change with time, intervention can be instituted with little documented detriment to the patient. Some would argue that the chance that these represent breast cancer is so small that short-interval follow-up is unnecessary, and they return these women to annual screening. Our routine has been to follow patients with probably benign findings at 6 months (unilateral), 12 months (bilateral mammography), 18 months (unilateral) and 24 months (bilateral). In our unpublished review of these patients, we found a few cancers had changed at 6 months, several at 1 year, and still others at 18 months. In addition, we occasionally find a cancer that is not the lesion that is being followed, but develops in another location. It is intuitively obvious and modeling has shown (2) that screening more frequently will pick up an additional number of cancers at a smaller size, so that this is a somewhat undefined advantage of short-interval follow-up. Based on our experience, we have retained short-interval follow-up as every 6 months for a total of 2 years. It may be shown that this is not particularly cost effective, but there is no contraindication to short-interval follow-up.

The principle of short-interval follow-up lies in the fact that probabilities are fractions and multiplicative. A lesion that has probably benign characteristics has a very low probability of being malignant to begin with. Although there are cancers that can be stable for many months to even years, these are extremely uncommon, and the probability of a cancer being stable is also a low probability. If a lesion begins with a low probability of being cancer and is then stable for several years, the low probabilities multiply, making an extremely low probability that the lesion is malignant. For example: If a lesion has 1 chance in 50 of being malignant based on its appearance, and if 1 in 100 cancers are stable over time, the chance of the lesion being cancer and being stable = 1/50 × 1/100 = 1 chance in 5,000. This forms the basis of the short-interval follow-up.

By definition, patients placed in a short-interval follow-up category should have a low risk of having breast cancer (3). The advantage is that a large number of women are spared a biopsy that would produce benign results, while the few who have breast cancer still have a good chance of having it detected earlier. One of the problems with short-interval follow-up is that short-interval follow-up can produce anxiety among some women. In at least one study, however, the anxiety produced by an immediate biopsy was greater than that produced by short-interval follow-up (4). When clinicians raise concern over a request for short-interval follow-up, we point out that most breast surgeons will not merely dismiss a clinically evident breast problem that they believe is probably benign, but they will request that the patient return for a short-interval follow-up, which in our experience is “after 1 or 2 menstrual cycles,” or 3 months. If the clinical examination is stable, then they extend

the follow-up interval. The precedent for short-interval follow-up comes from this clinical practice.

the follow-up interval. The precedent for short-interval follow-up comes from this clinical practice.

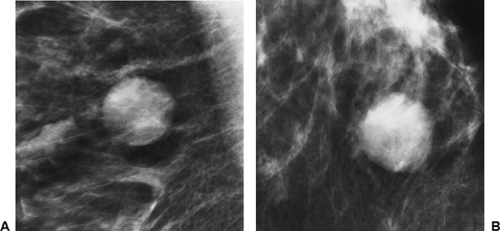

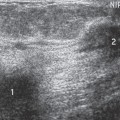

Most observers now accept the definition of probably benign lesions set by Sickles (5) in a landmark paper. Included in his categories were round or oval circumscribed masses (Fig. 15-1); smooth, round, clustered microcalcifications (Fig. 15-2); and focal asymmetric densities that did not represent masses. Magnification mammography was used to evaluate the margins of these lesions and the morphology of the calcifications. If the circumscribed lesions retained their sharp margins over 75% of the border, the remainder was obscured by normal tissues, the calcifications were round and regular, and the asymmetries did not form centrally dense masses fading toward their edges, Sickles found that these lesions together had only a 0.5% chance of malignancy over a 3-year follow-up period. For solitary circumscribed masses, there was a 2% chance that they were malignant. Focal asymmetries proved to be cancers only 0.4% of the time, while rounded calcifications were associated with malignancy in only 0.1% of the cases.

Varas et al (6) had similar results. Of the 21,855 who had been screened, they followed up, at short interval, 558 women with findings that were probably benign. Among those followed for an average of 26 months, 9 were found to have breast cancer (1.6%).

Sickles (7) has argued that management by mammographic surveillance is justified because (a) probably benign lesions indeed have a very low likelihood of malignancy; (b) mammographic surveillance will identify those few lesions that change in the interval that actually are malignant; and (c) these cancers will still be diagnosed early in their course, while they still have a favorable prognosis. It has become fairly well accepted that it is reasonable to fol-low a lesion that has a 2% or lower probability of cancer.

The MGH Approach to Short-Interval Follow-Up

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree