Pulmonary Infiltrates, Nodular Lesions, Ring Shadows and Calcification

Chapter 3 examined the relationship between the radiographic pattern of alveolar filling and the pathological process of consolidation. It sought to describe an analytical process whereby the differential diagnosis might be narrowed by systematic investigation of details and variations in the basic radiographic pattern. This chapter continues the theme of describing patterns of abnormal intrapulmonary shadowing and attempting to relate them to specific pathological entities – it concentrates on pulmonary infiltrations of various types, cystic shadows and the causes of intrapulmonary calcification. The diversity of abnormal intrapulmonary shadowing presents a huge challenge and is, at first sight, baffling. A fundamental aim of this chapter is to describe a systematic way of unravelling the complexities. Engaging a few simple rules when examining an abnormal pulmonary infiltrate can narrow the differential diagnosis to a few possibilities in many cases and result in a firm diagnosis in a significant proportion.

This approach is based on three lines of questioning:

1. The first asks whether a pulmonary infiltrate is actually present. This can be very difficult to decide when the abnormal shadowing is subtle and a useful arbiter is to question whether the normal vascular pattern is obscured. If it is, then it suggests that abnormal parenchymal shadowing is preventing clear definition of broncho-vascular structures in the lung fields because it has similar radiodensity unlike normal, aerated lung.

2. The second addresses the morphology of the abnormal shadowing.

3. The third concentrates on its distribution.

As with everything else in clinical medicine, there are no absolutes in these definitions and there will certainly be exceptions to the lists of differential diagnoses constructed from this approach. Nevertheless, the technique is useful because it is quick and practical and, most importantly, it is safe. This approach should be combined with other basic observations:

Are the lung volumes maintained?

Is cardiomegaly present?

Are there associated pleural, bony or mediastinal shadows?

Are there other specific radiographic appearances that give the diagnosis away? An example here is the close association between septal lines and the pathological diagnoses of left heart failure and lymphangitis carcinomatosa.

MORPHOLOGY OF THE SHADOWING WITH DEFINITIONS OF THE DESCRIPTIVE TERMS USED

It is essential to be absolutely clear about the meaning of the descriptive terminology. It is best to describe exactly what you see and avoid over-colourful terminology.

For example, describing a radiographic abnormality as ‘honeycombing’ is useful provided there is a strict understanding of what is meant by the terminology. The pathological causes of true generalized honeycombing are few and an accurate interpretation of its presence can be diagnostic.

For example, describing a radiographic abnormality as ‘honeycombing’ is useful provided there is a strict understanding of what is meant by the terminology. The pathological causes of true generalized honeycombing are few and an accurate interpretation of its presence can be diagnostic.

The definitions that follow are fairly standard and, although the measurements quoted are inevitably arbitrary, they are based on years of confirmed practical usefulness. It is important to practise using these terms, to become comfortable with them and to be strict about avoiding vague descriptions that are open to interpretation.

Circular shadows

These are best categorized according to size and all have well-defined borders.

Micronodular shadows. This is my preferred term and is better, I think, than the common synonyms ‘pinpoint’ or ‘fine mottling’. These rounded shadows are small – 1.5 mm or less in diameter).

Nodular shadows are larger, up to 2 cm in diameter.

Large circular shadows are 2 cm or more in diameter.

Ill-defined shadows

This is a descriptive term for poorly defined shadows. They may be reasonably defined and roughly circular or oval in shape, or have irregular boundaries in which case their appearance merges with that of patchy consolidation.

Linear and tubular shadows

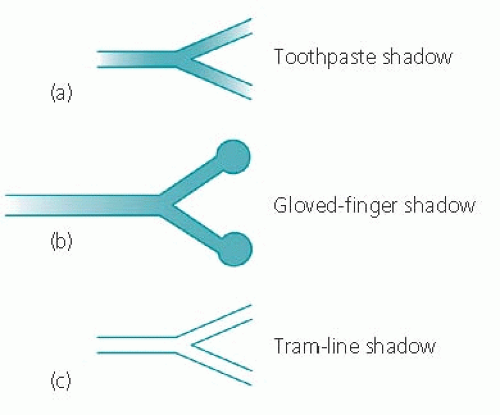

Linear shadows vary from ‘hair-line’ to 2 mm in thickness and include septal lines (see below) and the reticular component of reticulo-nodular shadowing. In his Principles of Chest X-ray Diagnosis (1978, Butterworth, London), Simon describes wider band-like shadows as ‘tooth-paste’ shadows and similar thickness linear shadows with bulbous ends as ‘gloved finger’ shadows (Fig. 4.1) – both probably represent mucus-filled bronchi. Tubular shadows are described as two more or less parallel fine lines that enclose a radiolucent area and the specific term ‘tram-line’ shadow can be used when the shadow is the expected size of a bronchus and occurs in a position and with the orientation to be expected of a bronchus. When this applies, the ‘tram-line’ represents a visible bronchus with thickened walls.

Figure 4.1 Diagram showing ‘toothpaste’, ‘gloved-finger’ and ‘tubular’ shadows (after Simon, G. Principles of Chest X-ray Diagnosis, 4th edn, 1978. Butterworth, London). |

The terms ‘toothpaste’, ‘gloved-finger’ and ‘tram-line’ are useful not only because the descriptions are clearly recognizable, but also because they point to a specific diagnosis – all three are usually associated with bronchiectasis.

Reticulo-nodular shadowing

The term ‘reticulo-nodular’ is used to describe a mix of linear and nodular shadowing in varying proportions. The nodular component is usually micronodular or small nodular in size.

Small ring shadows – the honeycomb pattern

I have used this term to describe thin-walled ring shadows each enclosing a relatively radiolucent zone and each measuring up to about 1 cm in diameter.

Larger ring shadows

Large ring shadows are usefully categorized according to two criteria: (1) their diameter; and (2) the thickness of their boundary wall. Bronchogenic cysts and congenital parenchymal cysts present radiographically as large ring shadows with thin walls.

A mycetoma classically presents as a large, thick-walled ring shadow. Cavitation within an area of consolidation can result in very similar appearances and definitions can become blurred under these circumstances.

Septal (interstitial or ‘Kerley B’ lines (see Fig. 4.2, page 79)

It is worth focusing on these particular linear shadows because they are diagnostically valuable when correctly identified. Septal lines are horizontally orientated, 1-3 mm wide and usually 1-2 cm in length. They are commonly multiple and most are seen in the area above the costophrenic recesses. They are particularly associated with left heart failure, lymphangitis carcinomatosa and coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis. The eponymous title, ‘Kerley B’ lines is commonly used, but I prefer to use the more descriptive terminology.

DISTRIBUTION OF ABNORMAL SHADOWING

The descriptions that follow are intended only as a guide. There are grey areas as far as the distribution patterns themselves are concerned and the differential pathological diagnosis listed against each is not exhaustive. Furthermore, the radiographic appearances of some disease processes are legion and it is almost pointless attempting to fit them into lists: leukaemia, lymphoma and drug-induced infiltrates are typical examples. Despite these qualifications, an attempt to distinguish basic patterns of distribution is a useful exercise in narrowing the disease possibilities for a particular pulmonary infiltrate, particularly when combined with a careful analysis of the component shadows as discussed above.

It is also important to realize that the radiographic appearances of the acute stage of a disease process may be very different from those that are typical of more chronic phases of the same condition – sarcoidosis and extrinsic allergic alveolitis both illustrate this point and examples follow.

The radiographic appearances of sarcoidosis have been usefully categorized into four stages:

stage 1 refers to hilar and/or mediastinal lymphadenopathy in the absence of pulmonary infiltration

stage 2 is the concurrent appearance of infiltration and lymphadenopathy

stage 3 occurs when lymphadenopathy has disappeared but the infiltrate remains

stage 4 is heralded by the advent of pulmonary fibrosis, usually manifest as upper zone shrinkage and increasing linear shadowing.

There are interesting epidemiological data from Sweden that record the relative frequency of these radiographic stages in individuals presenting with sarcoidosis or found fortuitously to have the disease on radiograph. The prevalence of presentation falls steadily from stage 1 through to stage 4, perhaps suggesting that the stages represent the natural history of the disease, which can spontaneously halt at any stage. Full spontaneous regression of the pulmonary appearance becomes progressively less likely as the stages advance.

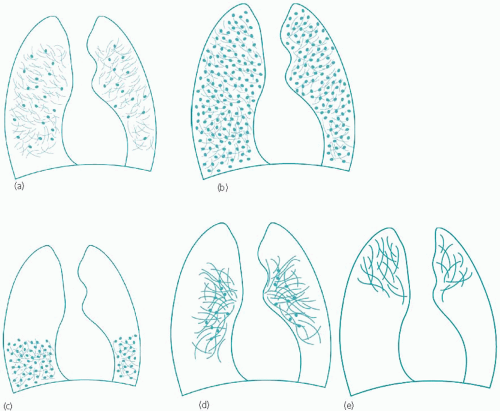

There are five schematic distribution patterns to consider and these are shown diagrammatically as reticulo-nodular infiltration in Fig. 4.2.

It is useful to consider these patterns in turn and in relation to the most likely pathological diagnoses that may be expected with each. The categories described below have been subgrouped according to the size of the nodular component.

All zones (Fig. 4.2b)

Micronodules:

miliary tuberculosis (see Fig 3.2, page 47 and Fig. 4.7); in Fig. 3.2, the backgound micronodules can still be distinguished although their profusion resembles widespread consolidation at first sight

coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis

sarcoidosis, a rare appearance (Fig. 4.8).

Small nodules:

pneumoconioses of various types including coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis (Fig. 4.9) and silicosis

pulmonary metastases, particularly from primary breast or thyroid malignancies (Fig. 4.10)

sarcoidosis (Fig. 4.11)

lymphangitis carcinomatosa (Fig. 4.12)

acute extrinsic allergic alveolitis (Fig. 4.13)

drug-induced (especially acute reactions, e.g. methotrexate lung – Fig. 4.14)

lymphoma (Fig. 4.15)

acute haemosiderosis

histoplasmosis

pulmonary eosinophilia (both Loeffler’s syndrome and tropical eosinophilia)

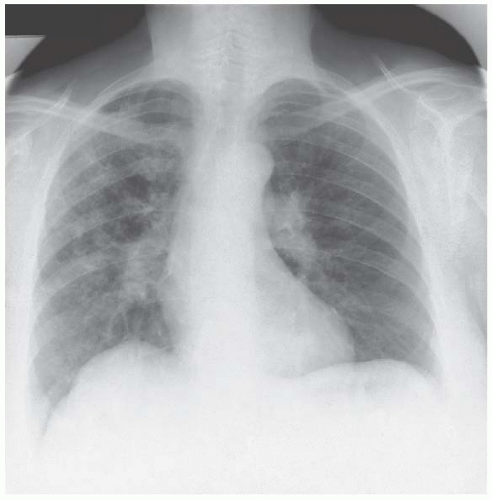

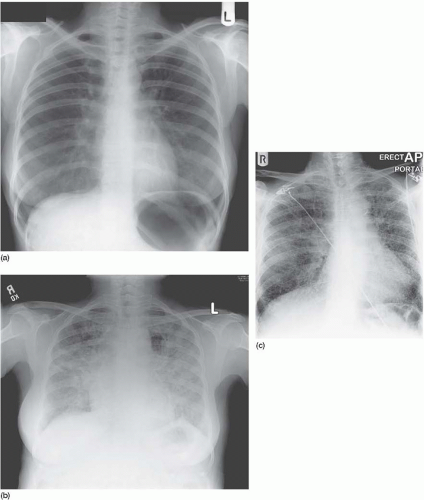

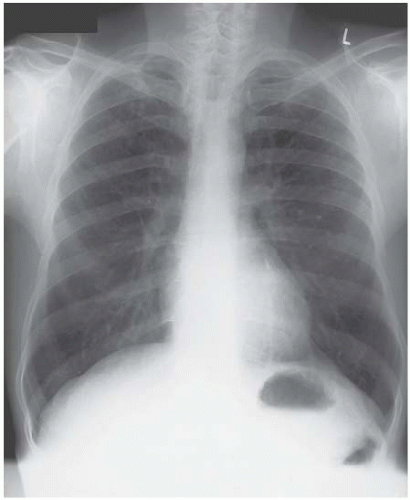

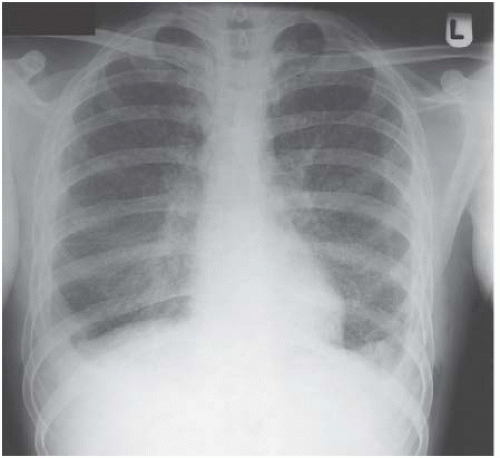

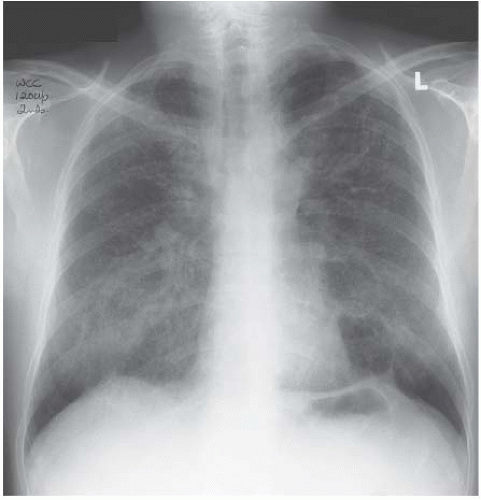

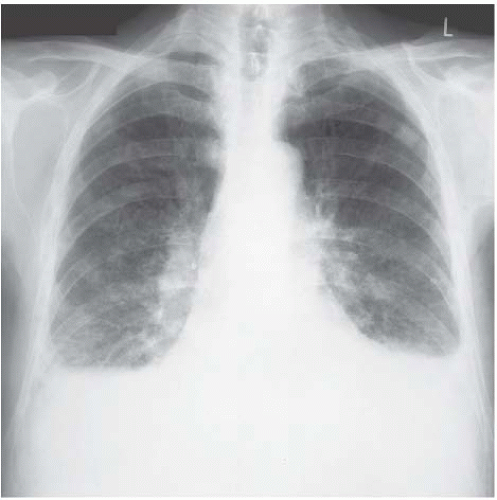

Figure 4.5 Coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis. The nodular infiltration in the mid-zones is subtle and the clue to its existence is the blurred outline of the vascular pattern.

Figure 4.6 Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia associated with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The mid-zone infiltrate is again given away by the obscured vascular pattern.

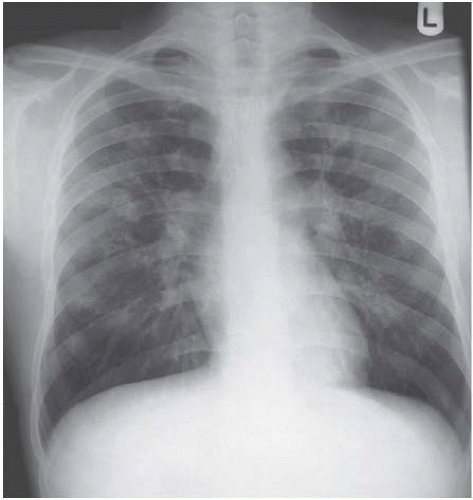

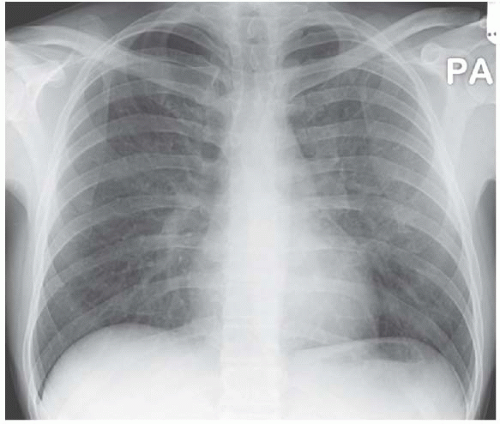

Figure 4.7 Miliary tuberculosis. The micronodules are everywhere, even infiltrating the apices, giving a big clue to the diagnosis.

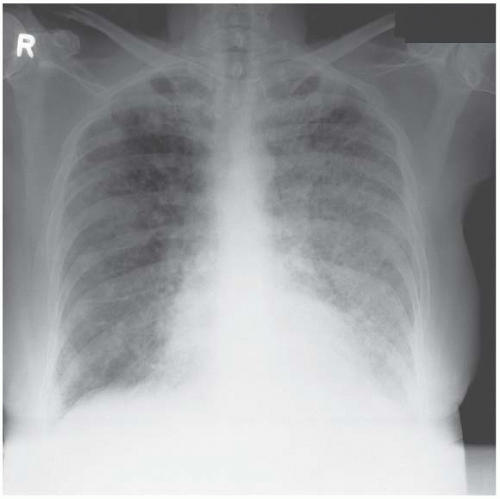

Figure 4.8 Widespread micronodular sarcoidosis is extremely rare and closely mimics miliary tuberculosis.

lymphangioleiomyomatosis/tuberous sclerosis (the infiltrate is a mix of nodules and micronodules, which may progress to develop classical honeycombing – Fig. 4.16, page 87).

Large nodules:

pulmonary metastases (Fig. 4.17, page 87).

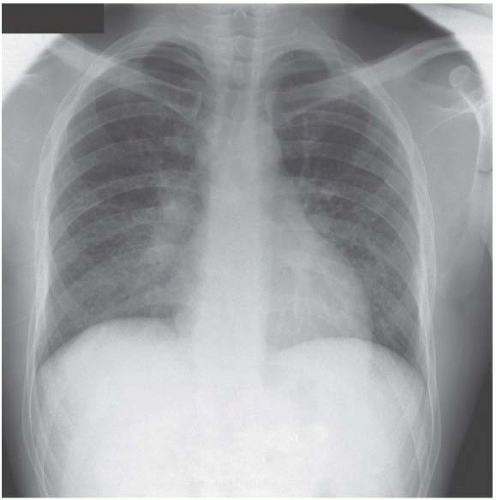

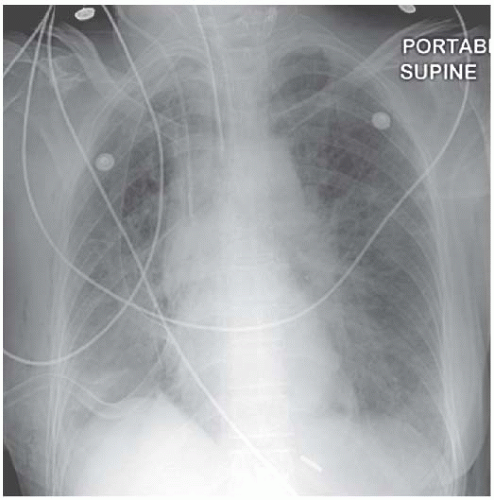

Figure 4.9 Coal-worker’s pneumoconiosis. The background nodulation is due to coal-dust deposition. The bilateral pleural effusions developed when this ex-miner developed nephrotic syndrome. |

Figure 4.12 Lymphangitis carcinomatosa from a breast primary. The chest drain was required to deal with a large right pleural effusion. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree