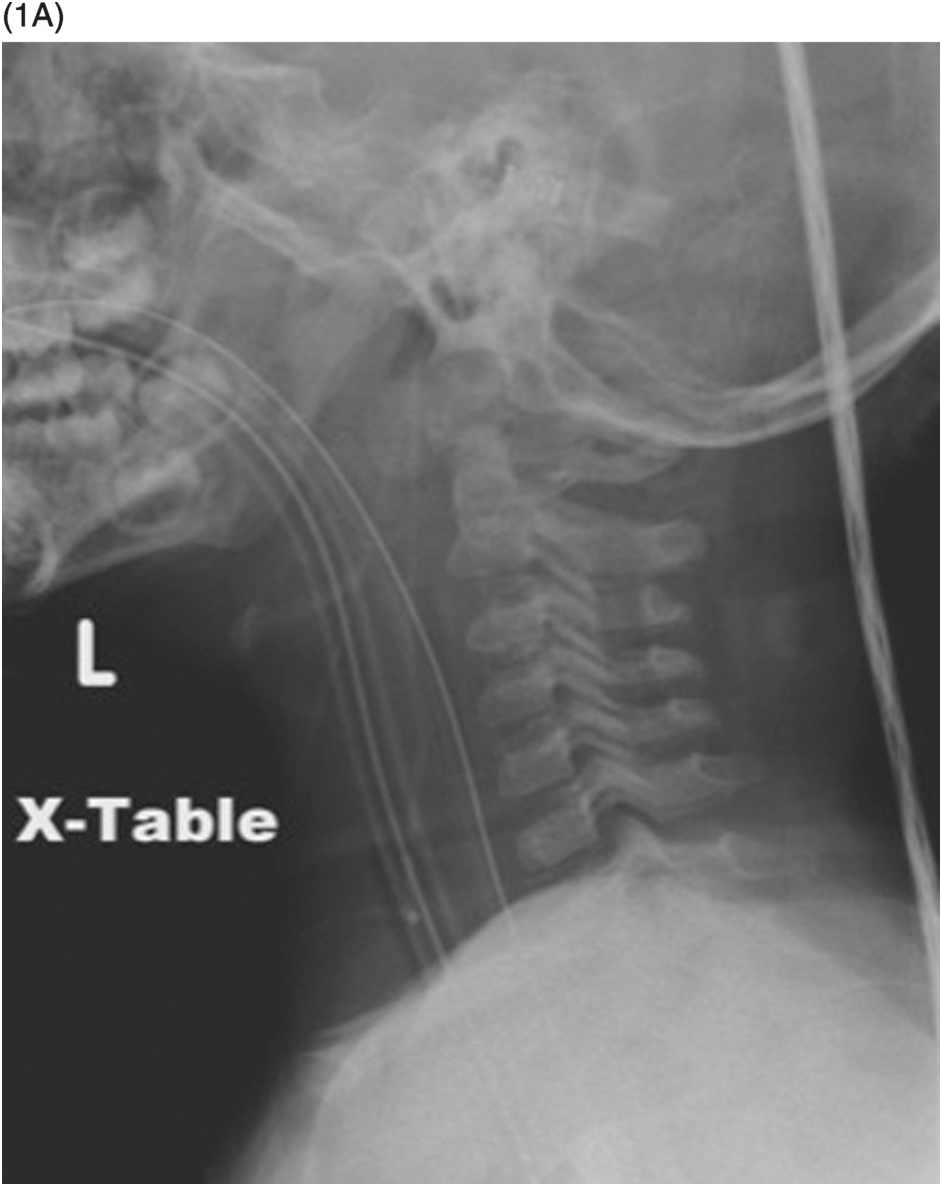

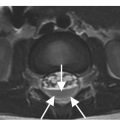

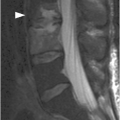

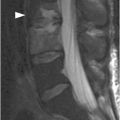

B) Midsagittal T2-weighted MR image reveals edema in the posterior soft tissues with disruption of the posterior ligamentous complex, disruption of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments, as well as spinal cord injury centered at the C5–C6 level.

Imaging Findings

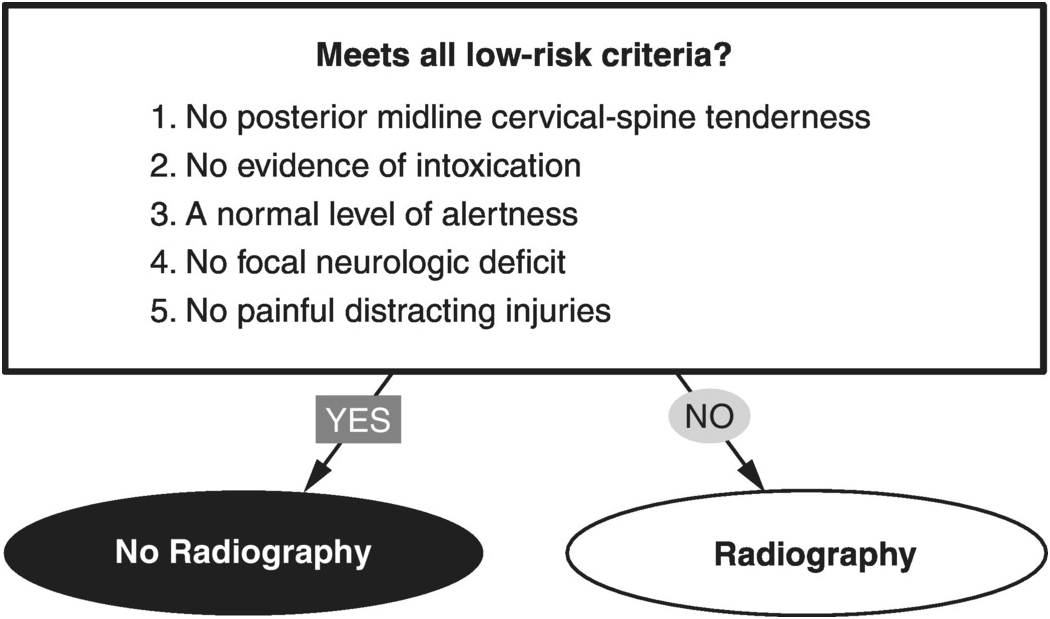

Two sets of clinical decision rules serve as guidelines for determining whether patients should have imaging of the cervical spine in the setting of trauma. NEXUS (National Emergency X-Ray Utilization Study) and the Canadian C-Spine rule identify individuals with a low probability of injury and therefore not warranting imaging. For those patients who do not meet the low-risk criteria, multidetector spiral (helical) non-contrast CT is the primary screening study. Coronal and sagittal reconstructions help improve detection of fractures and malalignment that can be difficult to visualize in the axial plane alone.

MRI allows evaluation of the spinal cord and other soft tissues, but it has a suboptimal sensitivity for fractures. With regards to spinal cord injury, MRI can offer prognostic information regarding potential recovery. Protocols should include sagittal T2w and STIR, as well as axial and/or sagittal gradient echo T2* sequences. Contrast agent is not required. While its role in the setting of acute trauma is controversial, it is the study of choice for determining the cause of neurological symptoms after a negative CT.

In contrast to the cervical spine, there are no established validated criteria for imaging the thoracolumbar spine in the setting of trauma. CT is routinely performed as first-line imaging to evaluate for acute injury. Given that trauma patients often undergo CT imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, data obtained from these scans can be used to evaluate the thoracolumbar spine avoiding the need for additional scan. MRI offers the same advantages as in the cervical spine, and is valuable for scoring the thoracolumbar spine injuries, as far as ligamentous injury is concerned.

Clinical Findings, Implications, and Treatment

Patients who have experienced blunt trauma and meet all five of the NEXUS criteria are classified as having a low probability of injury. The criteria are: (1) no midline cervical tenderness; (2) no focal neurologic deficit; (3) normal alertness; (4) no intoxication; and (5) no painful, distracting injury. The Canadian C-spine rule only applies to alert and stable trauma patients where cervical spine injury is a concern, and asks the three questions: (1) Is there a high-risk factor (age > 64, dangerous mechanism of injury, or paresthesia in extremities) mandating radiography? (2) Is there a low-risk factor (a simple rear-end motor vehicle collision, sitting position in Emergency Department, ambulatory since injury, delayed onset of neck pain, or absence of midline tenderness) that allows safe assessment of motion? (3) Is the patient able to actively rotate the neck 45° to the left and right? Imaging is not needed when there are no factors in question 1 present, at least one factor in question is 2 present, and the patient is able to complete the task in question 3.

Although less than 3% of blunt trauma patients have clinically important cervical spine injuries, the consequences of missed or delayed diagnosis are disastrous. Up to one-third of fractures involving the thoracolumbar spine are associated with spinal cord injury. The thoracolumbar junction (T10–L2) is especially vulnerable to injury in part related to the biomechanical transition from thoracic kyphosis to lumbar lordosis. The high sensitivity and specificity of CT warrants its use despite higher cost and radiation dose. Plain films have low accuracy and therefore should be abandoned.

Additional Information

The ACR appropriateness criteria for imaging in cervical spine trauma draw from both the NEXUS and Canadian C-spine rule. The recommendations are that no imaging is required in alert patients who have never lost consciousness, are not under the influence of drugs or alcohol, have no distracting injuries, have no cervical tenderness, and have no neurologic findings. Patients not fulfilling these criteria should proceed straight to CT.

References

Figure 10.1 A 2-year-old patient following an MVA. A) Lateral view radiograph seems negative. The patient is comatose, and MRI (B) is then performed, demonstrating spinal cord transection (arrowheads) and disruption of the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments as well as posterior ligamentous complex at C6–C7 level.

Adult Patients

One of the first questions when facing a patient with spinal trauma is whether the injury is stable or unstable. Stability is defined as the capacity of the spine to limit the segmental motion so as to not damage the neural structures and is provided by intact bones and ligaments. Radiographic images can answer this basic question in certain cases: plain films are a widely available, quick way to evaluate the spine. The question is: How to clear the cervical spine nowadays – with CT or plain films? Unfortunately, radiographs, even with the best possible technique, may underestimate spine injury. The main limitations of plain films are generally low sensitivity (65–85%), low accuracy for the craniovertebral junction, and poor visualization of C6 through T1 levels; also, linear or nondisplaced fractures can be difficult to detect, and fractures of the pedicle and uncinate process may not be seen. In the cervical spine, radiographs detect only 60–80% of fractures; a significant number of fractures are not visible, even when multiple views are performed. An advantage of plain films over CT or MRI is the relative ease of obtaining flexion-extension images, which can be active, when allowed by pain, or passive. Discussion over the safety and adequacy of this technique remains open.

CT has become the primary and only imaging modality in high-risk adult patients and can be simply added to the trauma CT protocol together with the evaluation of other anatomical regions.

Pediatric Patients

Plain films still play an important role for pediatric patients. There is currently insufficient data to support the routine use of NEXUS or CCR criteria in pediatric patients. It is generally agreed that imaging is necessary in symptomatic pediatric patients, but there are no current consistent guidelines on specific imaging indications or modalities. The absence of validated clearance protocols and controversy surrounding appropriate imaging result in significant variation in practice patterns. The current American Association of Neurological Surgeons consensus guidelines for symptomatic pediatric patients recommends screening radiographs followed by focused CT if abnormalities are present on the radiograph. In the setting of normal radiographs and pain with range of motion, a neurological deficit, or if the patient is intubated, an MRI of the cervical spine is usually obtained.

The largest multicenter study performed to assess sensitivity of radiographs was through the PECARN (Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network), in which the radiology reports of 186 pediatric patients under the age of 16 years with known cervical spine injury were reviewed. The authors reported an overall sensitivity of 90% (95% CI 85–94%), which was lower for children 7 years of age or younger (83%, 95% CI 70–92%), compared with children between the ages of 8 and 15 years (93%, 95% CI 88–97%). Other small retrospective studies in pediatric trauma patients have reported similar sensitivities. On the other hand, there are many limitations in accurately assessing the radiation dose of a single CT examination, as well as interpreting the significance of this radiation exposure within the context of an individual patient’s overall risk for developing cancer. There is evidence that the tube current and tube potential can both be substantially decreased when performing CT of the spine, without significant detrimental effect on diagnostic utility. Iterative reconstruction instead of filtered back projection image reconstruction further decreases the dose. Whatever the present risk is, it will continue to decrease as CT hardware and software continues to develop and improve.

References

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree