Sinonasal Cavities

CHOANAL NARROWING

KEY FACTS

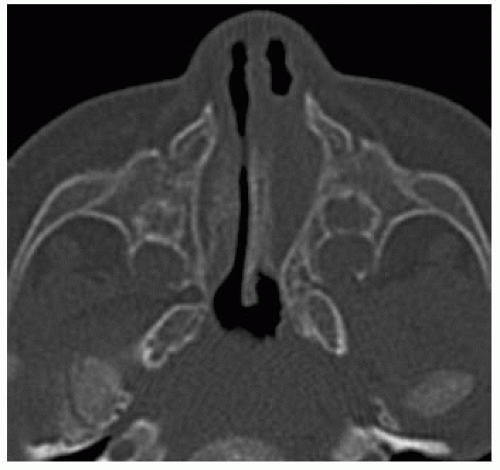

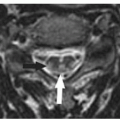

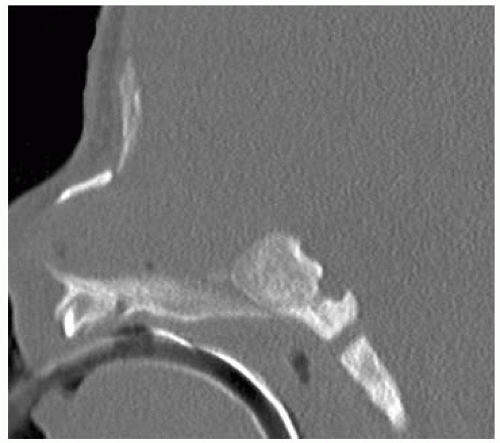

Can be of two types: stenosis and atresia (note: severe stenosis behaves clinically like atresia), further subdivided into bony or soft tissue (plugs); for bone stenosis, always measure the thickness of the palate, the diameter of choana (if any), and thickness of vomer; for soft tissue stenosis/atresia, always measure the thickness of plug and obtain computed tomography (CT) after administration of decongestants.

Bilateral is generally found in newborns, is accompanied by systemic abnormalities, is part of many syndromes, and needs immediate treatment regardless of type.

Unilateral presents later in childhood and even in adults; the most common symptom is chronic unilateral obstruction with or without infection; may require surgical treatment.

If accompanied by hypotelorism, always examine the brain for midline abnormalities.

Remember to obtain CT with high-resolution bone settings, angle images about 10 degrees cephalad to hard palate; give patients decongestants before and if need aspirate secretions.

Size of normal choanae: never <3.4 mm.

Size of normal vomer: never > 5 to 6 mm.

FIGURE 29-2. Midsagittal CT reformation, in a different patient, shows fusion of the hard palate with ventral clivus in severe stenosis (also called nasopharyngeal atresia). |

FIGURE 29-4. Parasagittal CT reformation, in a different patient, shows thin bone atretic plate (arrow). |

FIGURE 29-6. Nearly corresponding bone window in same patient as 29-5 shows the stenosis and plug better. |

SUGGESTED READING

Petkovska L, Petkovska I, Ramadan S, Aslam MO. CT evaluation of congenital choanal atresia: Our experience and review of the literature. Aust Radiol 2007;51:236-239.

DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES OF THE OSTIOMEATAL COMPLEX

KEY FACTS

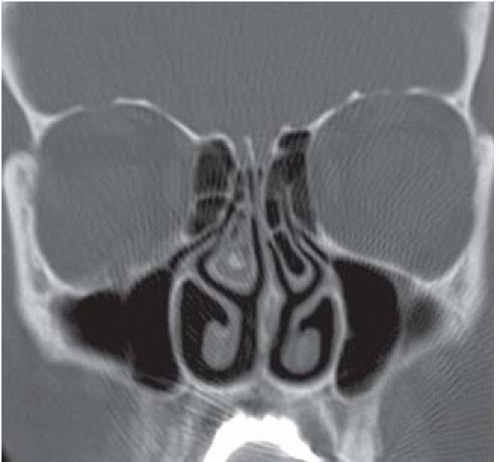

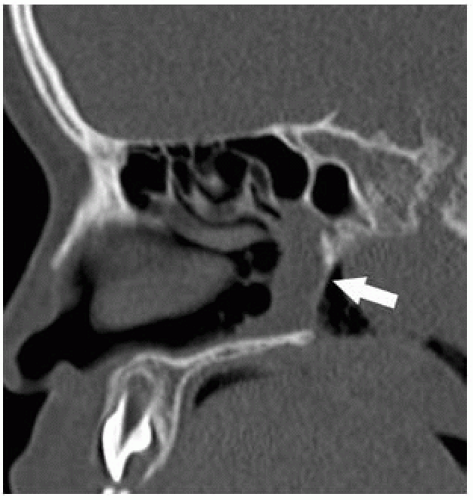

Developmental anomalies of the ostiomeatial unit include concha bullosa, paradoxical middle turbinates, septal deviation, enlarged ethmoid bullae, pneumatization of the uncinate process, and Haller cells (infraorbital extension of the ethmoid).

A concha bullosa (extramural middle turbinal cells) is present in 30% to 55% of the population; if large, it may deviate the nasal septum or become superinfected (concha bullitis, develop a mucocele or pyomucocele); if its ostium is occluded, a mucocele may form.

Paradoxical middle turbinates are common and diagnosed when their curvature is the reverse of the curvature of the inferior turbinates; if small, they are usually bilateral; if large, they are unilateral and may produce septal deviation.

Hypoplasia of the middle turbinates is uncommon and does not produce symptoms.

Enlarged ethmoid bullae and/or Haller cells may result in obstruction of the ipsilateral or contra-lateral infundibula.

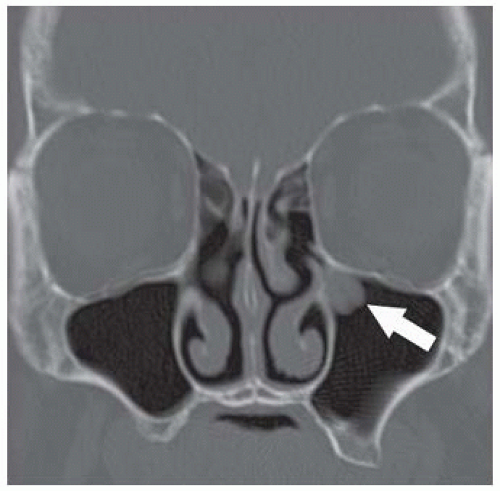

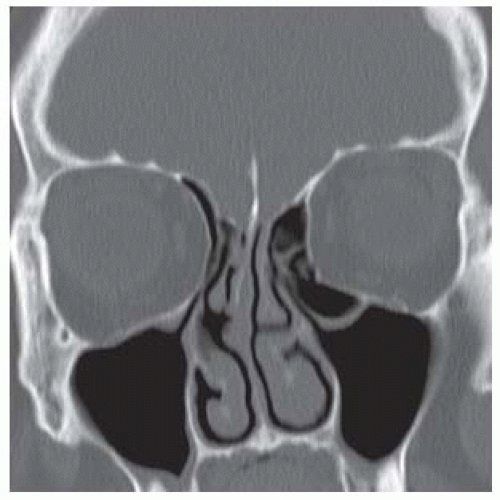

FIGURE 29-7. Coronal CT shows large left Haller cell with accompanying medial deviation of the ipsilateral uncinate process. |

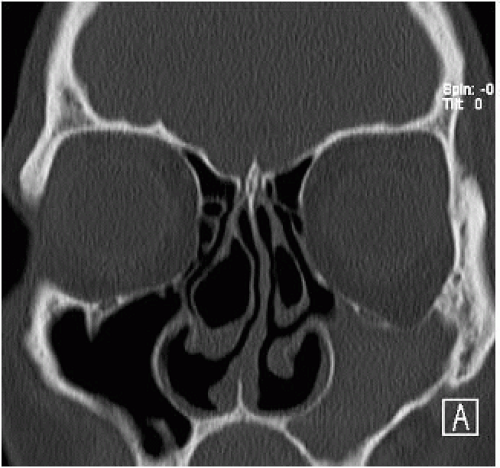

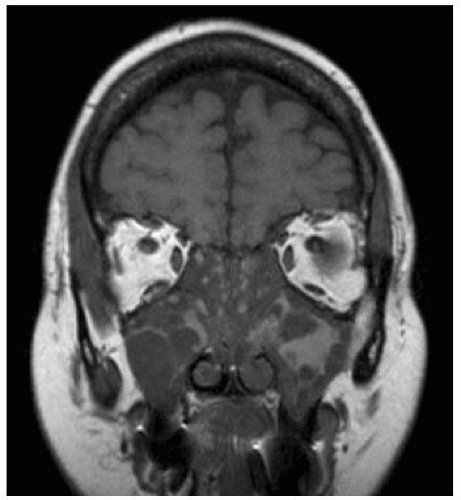

FIGURE 29-9. Coronal CT, in a different patient, shows large bilateral concha bullosae in middle turbinates with the left septal deviation and an opacified left maxillary sinus. |

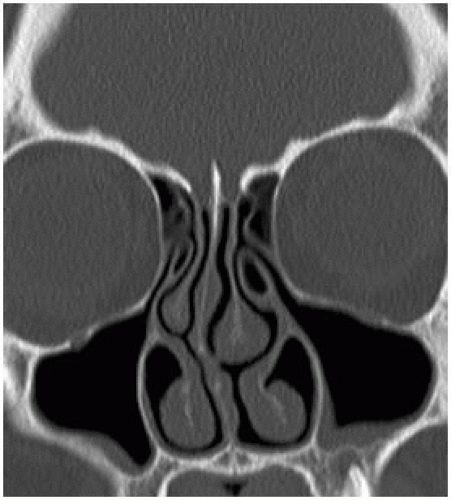

FIGURE 29-10. Coronal CT, in a different patient, shows an aereated left uncinate process. There is mild mucosal thickening in the alveolar recesses of both maxillary sinuses. |

SUGGESTED READING

Earwaker J. Anatomic variants in sinonasal CT. RadioGraphics 1993;13:381-451.

OSTIOMEATAL UNIT, OBSTRUCTION

KEY FACTS

The ostiomeatal unit (OMU) is formed by

Uncinate process: thin bone lamina belonging to the ethmoid bone, which begins anteriorly at the lacrimal bone and extends posteriorly to the inferior nasal concha.

Ethmoidal infundibulum: air space located superolateral to the uncinate process and inferior to the ethmoidal bulla.

Semilunar hiatus: air space above the uncinate process and inferior to the ethmoidal bulla, communicating the infundibulum with the middle meatus.

Ostia for the maxillary, anterior, and middle ethmoidal complex, and frontal recess form the medial aspect of infundibulum.

The OMU may be obstructed by mucosal thickening, polyps, enlarged or pneumatized uncinate process, deviated nasal septum with or without spurs, concha bullosa of the middle turbinate, large ethmoid bullae, and paradoxical middle turbinates.

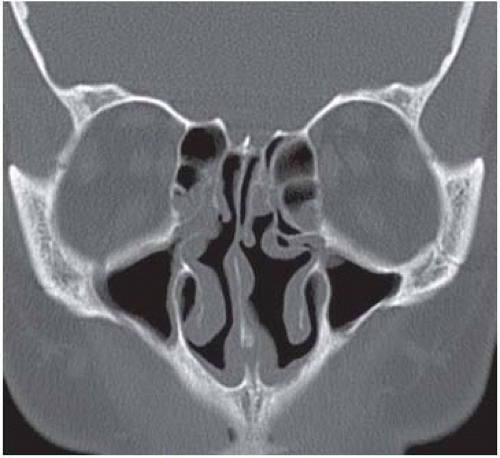

FIGURE 29-12. Coronal CT, in a different patient, shows polypoid mucosal thickening obstructing both infundibula. Middle turbinates are very hypoplastic. |

SUGGESTED READING

Kantarci M, Karasen RM, Alper F, Onbas O, Okur A, Karaman A. Remarkable anatomic variations in paranasal sinus region and their clinical importance. Eur J Radiol 2004;50:296-302.

MUCOUS RETENTION CYSTS

KEY FACTS

Generally, they are the sequelae of inflammatory sinusitis, allergy, or trauma and should be distin-guished from just polypoid mucosal thickening.

They represent obstruction of a minor salivary gland or a mucus-secreting gland.

They occur in more than 10% of population, most commonly in the maxillary sinus.

They are usually incidental and asymptomatic findings.

If small, they have an upward convex border; if large, their superior surface becomes flattened, and they may simulate a fluid level; if very large, they may obstruct the sinus ostia.

Caution: in adults, early paranasal sinus carcinoma may appear identical to a mucous retention cyst.

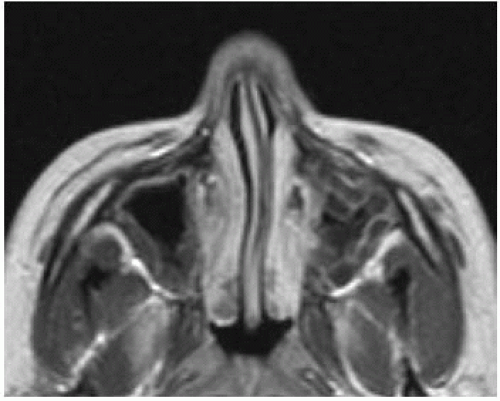

As with most inflammatory sinus disease, retention cysts are bright on T2 images.

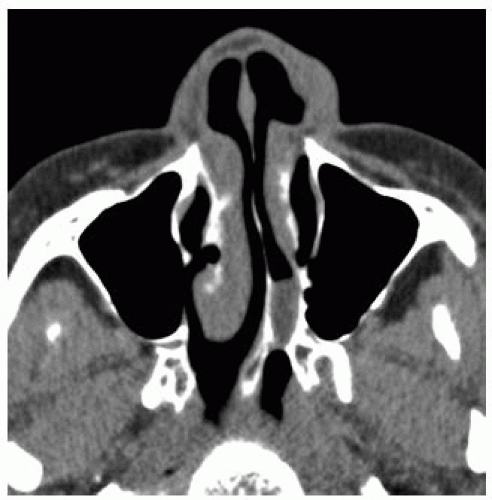

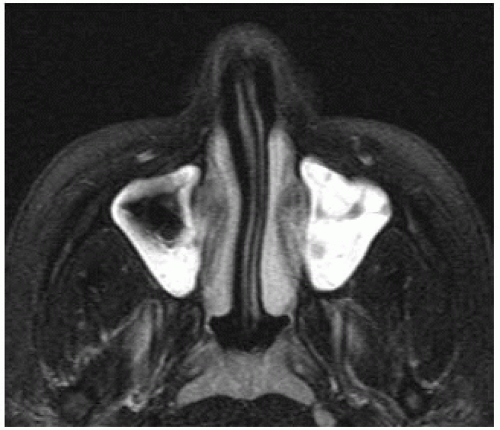

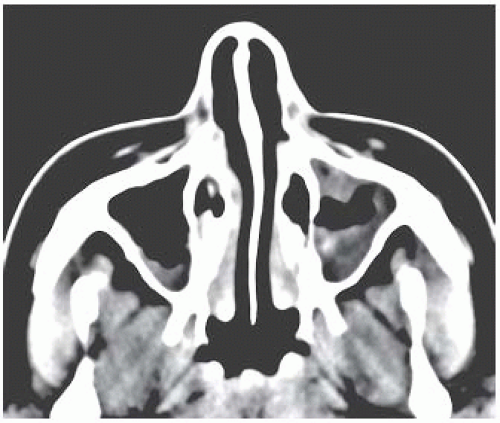

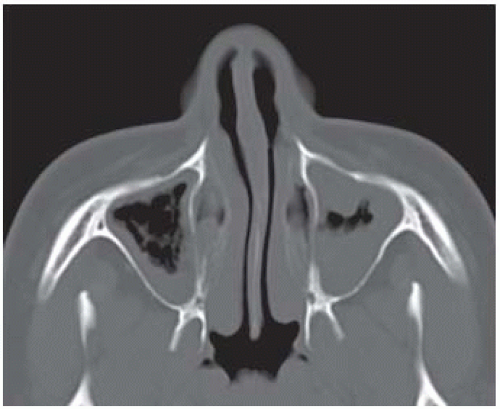

FIGURE 29-13. Axial CTshows mostly low-density mucosal thickening in both maxillary sinuses (left > right). |

FIGURE 29-14. Corresponding bone window setting better shows the “polypoid” nature of the mucosal thickening. |

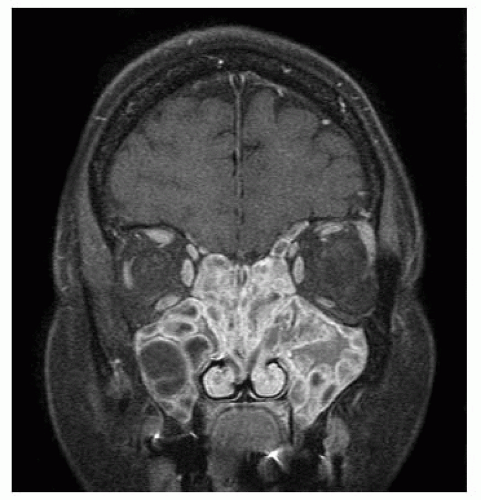

FIGURE 29-16. Corresponding postcontrast T1 shows that mucosa on surface of mucous retention cysts enhances, while the retained submucosal secretions do not enhance. |

SUGGESTED READING

Hudgins PA. Sinonasal imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 1996;6:319-331.

SINONASAL POLYPS

KEY FACTS

Polyps are usually the sequelae of inflammation, vasomotor and/or infectious rhinitis, diabetes, and cystic fibrosis.

Polyps in children are uncommon in the absence of cystic fibrosis; overall they are found in 4% of the population and are more common in males, and asthma is an important predisposing factor.

Polyps may occur in any sinus (but are more common in the maxillary sinus) and may enlarge and become a conglomerate mass, which expands the sinuses and the infundibula, erodes their septa, or results in loss of bone density in the ethmoid trabeculae, turbinates, and nasal septum.

Occasionally, they behave aggressively and erode bone (producing intracranial extension) particularly those arising the frontal and sphenoid sinuses.

Polyps may protrude from a sinus into nasal cavities (antrochoanal and sphenochoanal polyps).

Polyposis may be infected with fungi (generally Aspergillus) and by CT show high density and/or calcifications (25% to 50%, due to calcium phosphate and calcium sulfate in necrotic mycetomas).

Infarcted polyps may be hyperdense on noncontrast CT; the presence of low T2 signal intensity does not imply malignancy but correlates with desiccated secretions and/or fungal infection.

Main differential diagnosis: retention and mucosal cysts, allergic fungal sinusitis, Wegener granulomatosis.

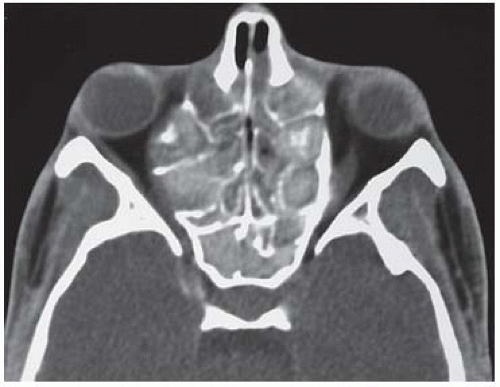

FIGURE 29-17. Axial CT shows expanded ethmoid sinuses that contain some residual thickened septa and are expanded. Most of the secretions contained are dense. |

FIGURE 29-18. Coronal CT, in the same patient, shows ethmoid sinus expansion and multiple areas of bone erosion. |

FIGURE 29-19. Coronal noncontrast T1, in the same patient, shows proteinaceous retained bright secretions and low-intensity polyps. |

SUGGESTED READING

Zeifer B. Pediatric sinonasal imaging: normal anatomy and inflammatory disease. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2000;10:137-159.

ACUTE (UNCOMPLICATED) SINUSITIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree