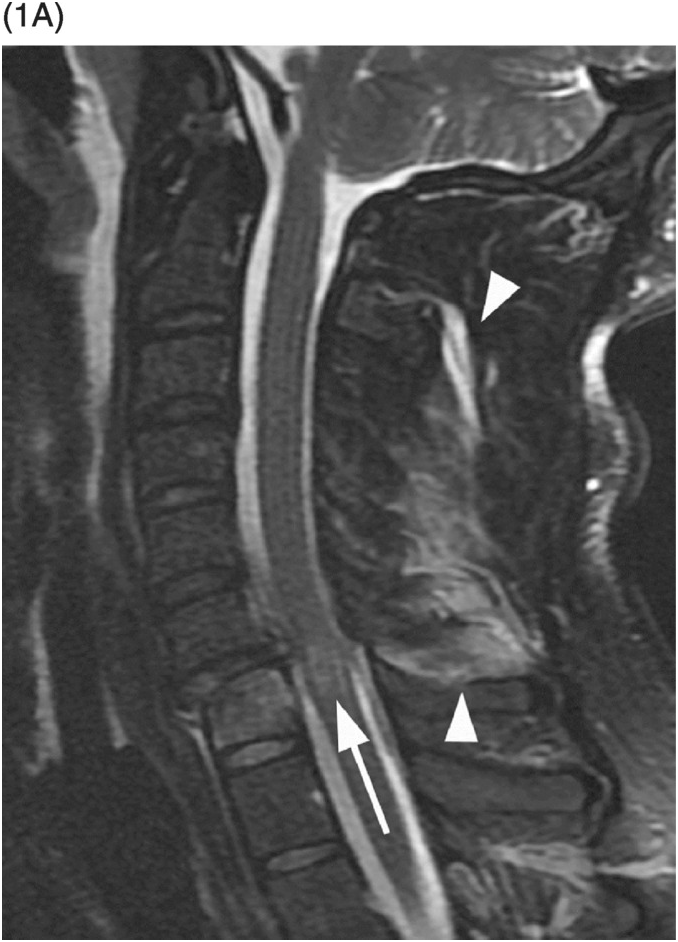

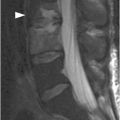

Figure 34.1 Midsagittal T2w (SE) (A) and T2*w (GRE) (B) MR images shows traumatic subluxation of C6 over C7 and traumatic C6–C7 disk herniation. There is spinal canal compromise with mild compression of the spinal cord and elevated intramedullary T2 signal consistent with edema (arrow). There are no focal areas of signal loss on the T2* images to suggest focal cord hemorrhage. Note posterior ligamentous injuries (arrowheads).

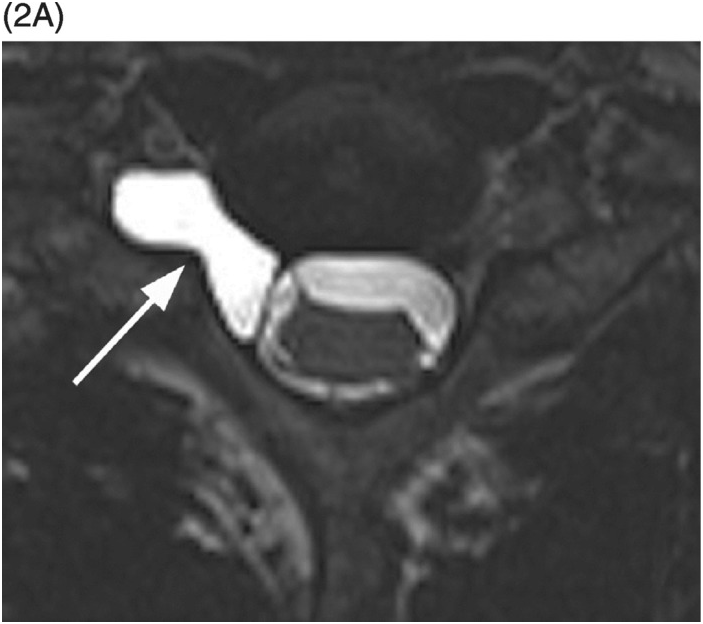

Figure 34.2 A) Midsagittal T2w (SE) MR image shows fracture of the odontoid. Posterior distraction of the superior fracture fragments contributes to the spinal canal stenosis and mild spinal cord compression. Areas of high and low T2 signal intensity (arrow) are consistent with hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic spinal cord injury, respectively. Intramedullary hemorrhage is clearly seen as an area of signal loss (arrow) on the corresponding T2*w (GRE) image (B).

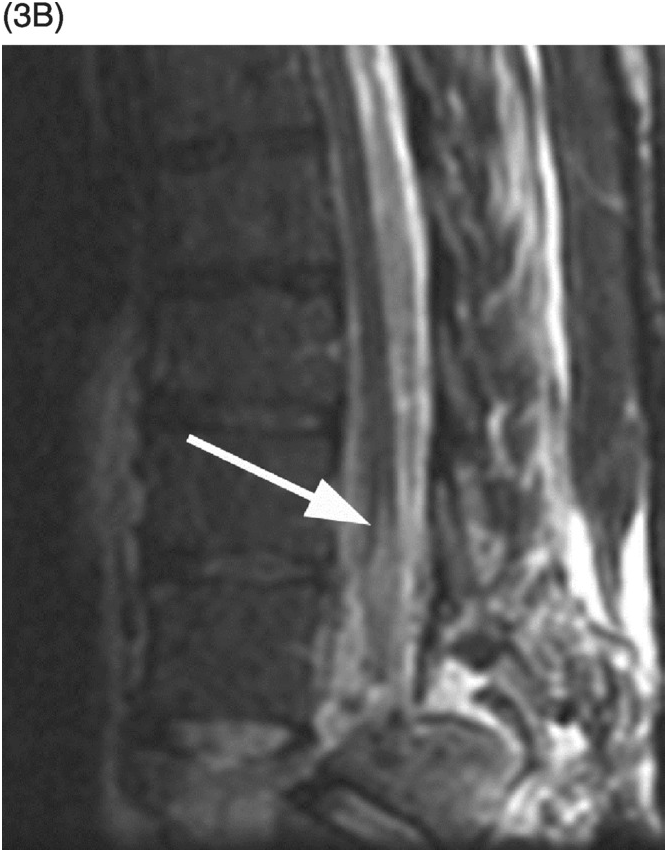

B) MRI confirms spinal cord transection at the T10–11 level and intramedullary edema (arrow) extending to T9 level.

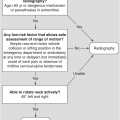

Imaging Findings

Acute injuries to the spinal cord can be classified as contusions or transections. Contusions can be hemorrhagic or non-hemorrhagic. Type I injuries represent intramedullary hematoma and demonstrate heterogeneous T1 and low T2 signal with rim of higher T2 signal related to edema. Intramedullary hemorrhage is best seen on T2*w (gradient-echo or susceptibility-weighted) images as a very dark lesion/an area of signal loss. Type II injuries reflect only edema within the spinal cord and are low to isointense on T1 and T2 hyperintense. Type III injuries are a mixture of hematoma and edema and are therefore low to isointense on T1 and show heterogeneous appearance on T2-weighted images. MRI demonstrates the level of spinal cord transection.

The presence of intramedullary hemorrhage and extended segments of edema have been associated with clinically complete spinal cord injury (SCI). An important prognostic imaging characteristic, in addition to intramedullary hemorrhage and edema, is the degree of spinal cord compression.

Differential Diagnosis

Nontraumatic Compressive Myelopathy

Degenerative disease resulting in severe spinal canal stenosis with spinal cord compression and edema.

Myelitis

Hyperintense T2 signal with or without contrast enhancement; mild fusiform enlargement of spinal cord without spinal canal stenosis.

Spinal Cord Infarction

Almost exclusively involves the gray matter, primarily the anterior horns, with the characteristic “owl’s eyes” appearance.

Syrinx

Cystic typically central cord lesion with longitudinal extension and variable spinal cord expansion.

Clinical Findings, Implications, and Treatment

SCI usually occurs in conjunction with bony and ligamentous traumatic lesions. Clinical findings will depend on injury location with C4–C6 being the most common level of adult spinal cord injury.

Patients with anterior cord syndrome present with variable impairment of motor function and pain and temperature sensation with relative sparing of propioception. It occurs with hyperflexion injuries, acute central disc herniation, and burst fractures with ventral cord compression.

Central cord syndrome is seen almost exclusively following cervical SCI. It is characterized by sacral sensory sparing and greater weakness in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs. This results from a lesion within the cord that afflicts the central gray matter and the surrounding fiber tracts. The peripherally located corticospinal lumbosacral fibers are spared, leading to relative preservation of lower extremity motor strength. Similarly, the laterally placed sacral spinothalamic tracts are preserved with preservation of sacral sensation. Posterior cord syndrome is uncommon.

Brown-Sequard syndrome is characterized by physiologic hemisection of the cord, producing ipsilateral motor weakness and impaired propioception with contralateral impairment of pain and temperature sensation. This syndrome usually occurs with other SCI or nerve root injury (or both) or brachial plexus injury. It is most often seen in cervical spine and less frequently in thoracic spine. This syndrome carries a favorable prognosis except when resulting from a penetrating injury.

Conus medullaris syndrome results from injury to the sacral spine segments and lumbar roots, at the T11 and T12 vertebral body levels. This part of the vertebral column is prone to injury because it lies in the transitional zone between the rigid thoracic spine and mobile lumbar spine. The patients can have a combination of upper and lower motor neuron paralysis. The deficit is usually symmetrical and involves the motor, sensory, and sphincter functions.

Cauda equina syndrome results from injury to the lumbosacral nerve roots of cauda equina in the canal from L2 vertebral body level downward. Clinical features include asymmetrical areflexic paralysis of lower extremities, sensory impairment in lumbar and sacral dermatomes, and lower motor neuron type bowel and bladder incontinence.

Type II spinal cord injuries are most common and will regress over 1–2 weeks, resulting in a more favorable prognosis. Type I and III spinal cord injuries are less common and have a poor prognosis, often without substantial neurological recovery.

Broad indications for surgical intervention following SCI include decompression of neural elements, stabilization of spine, and deformity correction. Stabilization is indicated for an “unstable” injury. Injury is considered unstable when there is progressive neurological decline, pain, or deformity of the spine under physiological loading. Surgery can range from simple decompression to instrumented fusion. Under most circumstances, some kind of stabilization would be required, as an isolated decompression can lead to persistent pain and late deformity.

Additional Information

Underlying degenerative disease predisposes older adults to spinal cord injury. Although more common in children, spinal cord injury can occur in the absence of bone or ligamentous injury and is referred to as SCIWORA (spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality, the more appropriate term would be spinal cord injury without CT evidence of trauma – SCIWOCTET).

References

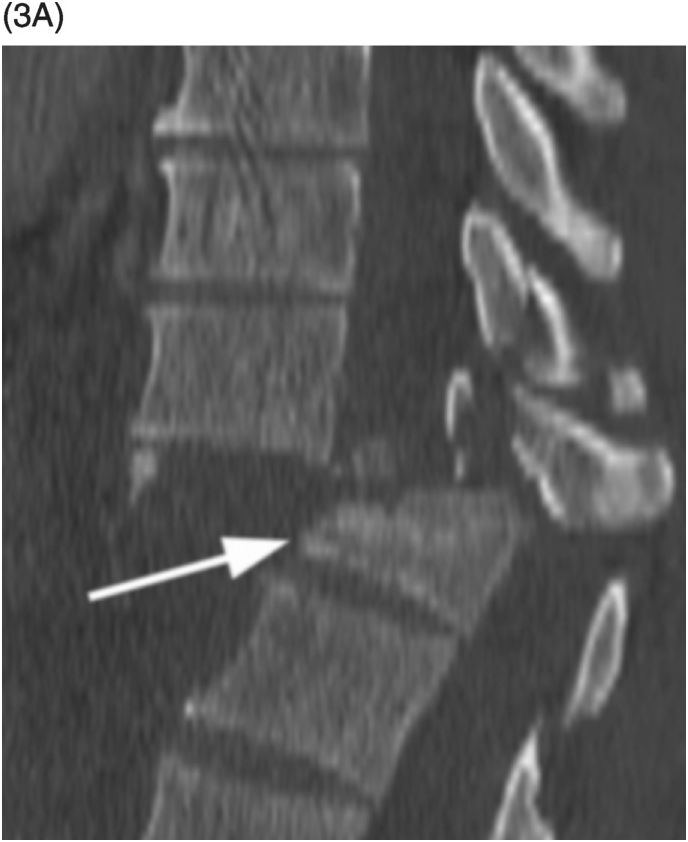

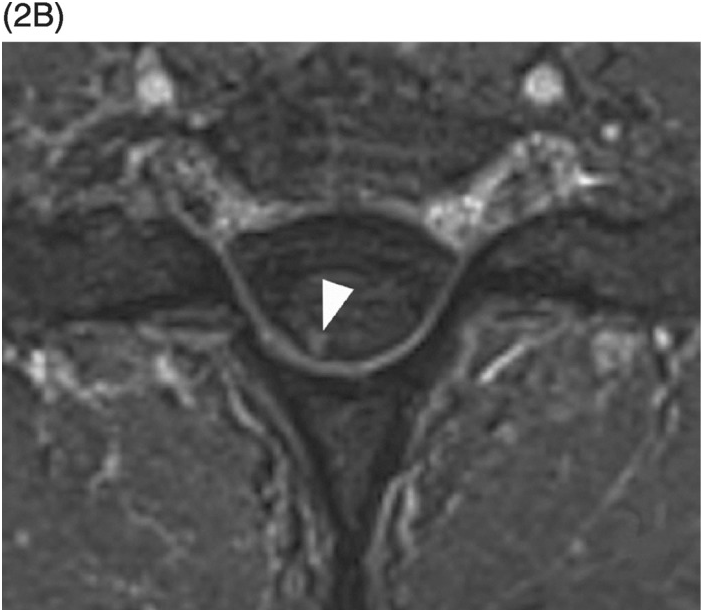

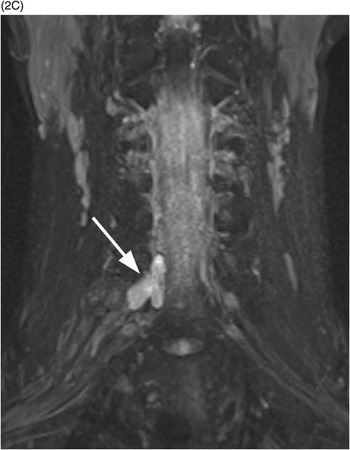

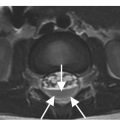

Figure 35.1 A) Axial T2* image shows a left C5–C6 CSF collection (arrow) consistent with pseudomeningocele and deviation of the spinal cord to the right. Axial (B) and coronal (C) CT-myelogram images confirm the pseudomeningocele (arrows) and show lack of visualization of the avulsed left dorsal C6 nerve root. Note normal adjacent nerve roots (arrowheads).

A) High-resolution axial T2w image shows a large pseudomeningocele at C6–C7 on the right (arrow) related to right C7 nerve root avulsion.

B) Fat-saturated post-contrast axial T1w image demonstrates enhancement of the right C7 dorsal nerve root stump (arrowhead).

C) Coronal MIP reformatted STIR image depicts the pseudomeningocele (arrow). The right brachial plexus shows subtle thickening and increased signal due to stretching injury of nerve roots.

Imaging Findings

Nerve root avulsion is typically seen as a pseudomeningocele – an extra-dural CSF pouch within and/or extending to the neural foramen, sometimes with mass effect on the dural sac. The spinal cord may be displaced contralaterally. Dedicated high-resolution 3D heavily T2w MRI (MR myelography) or CT myelography are very accurate for assessment of the pseudomeningoceles. MR myelography without intrathecal contrast administration is superior to CT myelography for small meningoceles, which do not fill with contrast when there is little or no communication with the dural sac, although its spatial resolution for detailed visualization of intradural nerve roots is lower. However, visualization of rootlets in the absence of pseudomeningocele may not be helpful in detection of complete nerve root avulsion. MRI also shows contrast enhancement of the injured intradural nerve roots, suggesting functional impairment despite morphologic continuity, which is seen in approximately 20% of patients with preganglionic injuries. Furthermore, abnormal enhancement of paraspinal muscles on post-contrast fat-suppressed T1w images, consistent with acute denervation injury, is an accurate indirect sign of nerve root avulsion.

Differential Diagnosis

Spinal Extradural Arachnoid Cyst (Extradural Meningeal Cyst)

Outpouchings of the arachnoid through a congenital or acquired dural defects usually located in the mid-to-lower thoracic spine, which may protrude into the neuroforamen and remodel it. The signal within the cyst may appear T2 hyperintense compared to the CSF due to higher protein content. CT myelography is helpful in establishing communication of the cyst with the subarachnoid space.

Meningocele

CSF-filled protrusion of the dura mater and arachnoid that extends through an enlarged intervertebral foramen, most commonly seen in patients with mesenchymal disorders such as neurofibromatosis, Marfan’s syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Clinical Findings, Implications, and Treatment

Nerve root avulsion, including neonatal brachial plexus palsy, results from stretch injuries. This type of injury is seen most commonly in cervical and upper thoracic region involving the brachial plexus, but is rare in the thoracolumbar region. Meticulous clinical examination, supplemented by electrodiagnostic and imaging studies, can establish the level (roots involved), extent (partial or complete), and nature (avulsion or rupture) of injury. The primary objective of imaging is to identify nerve root avulsion indicative of preganglionic injury. Treatment of nerve root injuries, usually referred to as brachial plexus injuries, may be either conservative or surgical: surgical procedures include neurolysis, nerve grafting, and nerve transfer.

Additional Information

Preganglionic nerve root avulsions are subdivided into peripheral and central: peripheral lesions occur when a traction force avulses the fibrous supporting tissues around the nerve rootlets; central mechanism of root avulsion is the result of displacement of the spinal cord, as cord bending induces avulsion of the rootlets without a rupture of the epidural sleeve. Extremely rare cases of transdural spinal cord herniation into the pseudomeningocele have been described. Postganglionic lesions involve the nerve distal to the sensory ganglion and are further classified into nerve ruptures and lesions in continuity. Differentiating preganglionic from postganglionic lesions is crucial to the management of plexus injuries. In preganglionic injuries, function of some of the denervated muscles may be restored with nerve transfers. Postganglionic lesions generally have better prognosis and can be repaired with neurolysis, nerve grafting, nerve transfer, or managed conservatively.

References

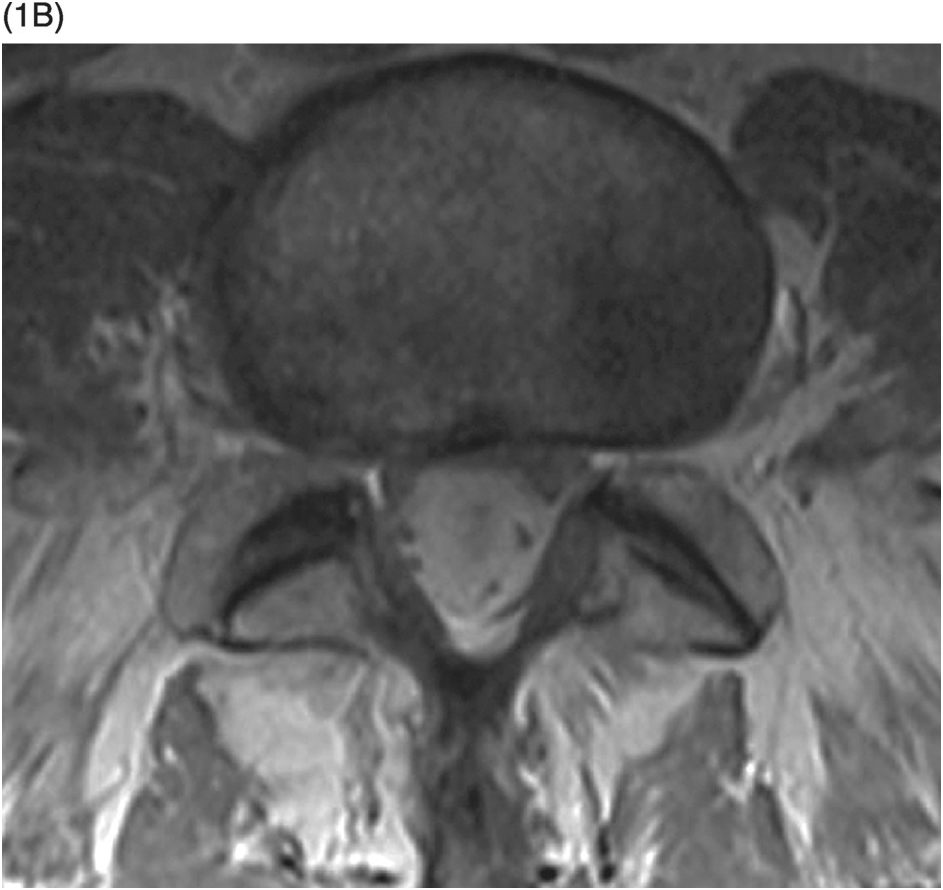

B) Axial T1-weighted image at L5–S1 level has the appearance of a T2-weighted image within the spinal canal showing dark nerve roots on the background of bright CSF.

A) Sagittal T1-weighted reveals as a bright lesion (arrow) along the posterior aspect of the thecal sac centered at S1 level. The lesion is separated by a dark line of dura from the posterior epidural space.

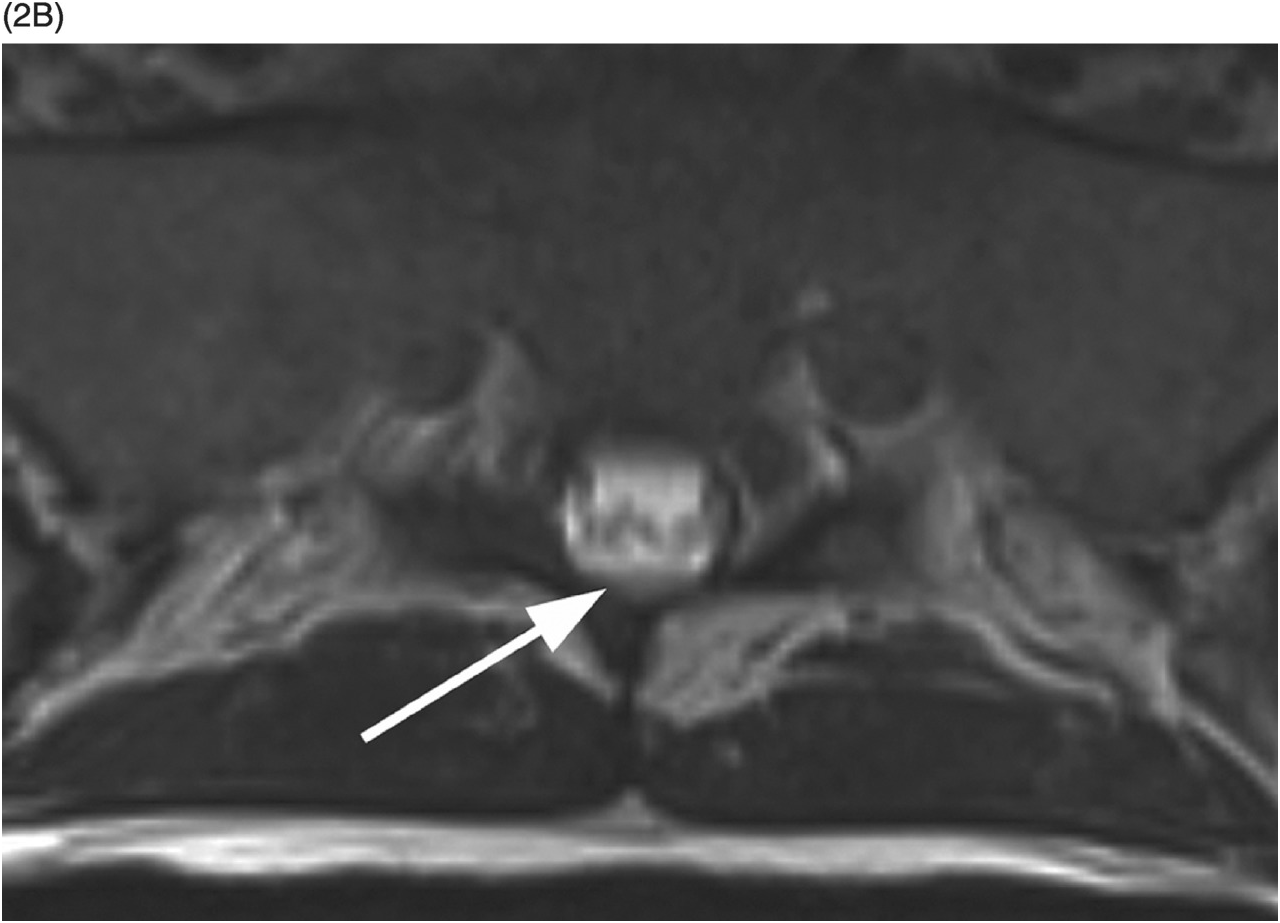

B) Axial T2-weighted image shows a small area of relatively lower signal (compared to the CSF, isointense to the cauda equina nerve roots) with layering along the posterior aspect of the dural sac (arrow) with a fluid–fluid level. The findings are consistent with a small amount of spinal SAH, which has presumably migrated from the intracranial SAH.

Imaging Findings

Spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SSAH) is found within the thecal sac in an intradural extramedullary location, either diffusely extending over a number of spinal levels and/or as a focal clot. The hematoma may show a fluid–fluid level, typically at the inferiormost aspect of the dural sac or at other dependent portions (thoracic spine in supine position), but may also be ventral to the spinal cord/cauda equina. Compared to the CSF, SSAH is hyperintense on T1-weighted images and usually of lower T2 signal intensity, although it may be T2 isointense and even hyperintense (in the hyperacute stage). It is rarely of very bright T1 and very dark T2 signal, presumably due to dilution with a relatively large volume of the CSF; however, a substantial amount of diffuse subarachnoid blood may lead to a misleading “T2-like” intradural appearance on T1-weighted images. The subarachnoid clot does not enhance with contrast and may displace the nerve roots of the cauda equina, frequently periferally. Larger amounts of SSAH may sometimes be seen on CT as intradural focal hyperdense masses and/or increased attenuation of the CSF.

Differential Diagnosis

Subdural Hematoma

The blod clots are separated from the CSF usually by a number of septations, giving the peripheral crescentic “Mercedes star” sign on the axial MR images; there are no fluid–fluid levels and dark signal of the dura separates these collections from the epidural fat. Spinal subdural hematoma and SAH may be coexistent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree