Suspicious Lesions and Lesions with a High Probability of Malignancy

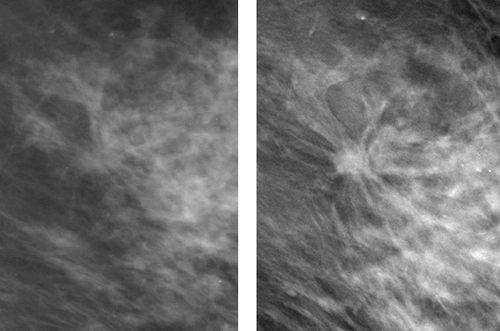

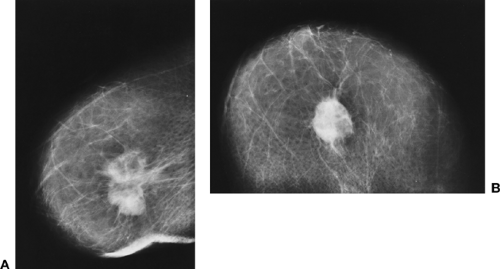

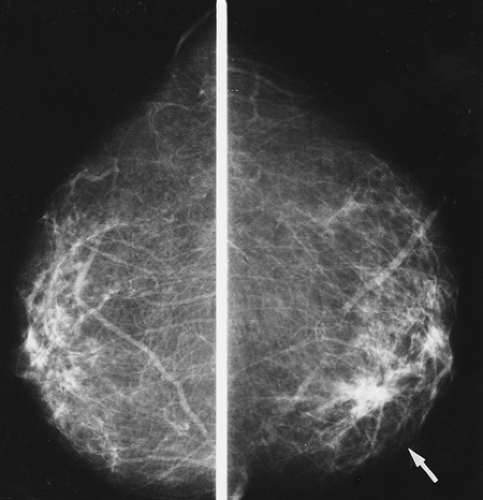

The classic description of a breast cancer is a mass with an irregular shape and spiculated margin (Fig. 16-1). It has been our experience that many cancers that appear ill-defined on conventional, two-dimensional mammography appear so because their spiculated margins are hidden by superimposed tissues. By eliminating the “noise” of superimposed normal breast structures, many more cancers appear to have spiculated margins on digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) (Fig. 16-2). Diagnosis would be greatly simplified if all cancers of the breast exhibited similar unique features, but unfortunately they do not. Although many cancers have specific recognizable morphologic characteristics, there is an unavoidable similarity among the shapes, margins, and densities of many benign and malignant lesions. Some cancers produce an appearance that is virtually pathognomonic of the disease, but many do not exhibit such specific morphology. Until there are accurate, noninvasive ways to differentiate benign lesions from those that are malignant, some benign lesions will necessarily be biopsied to maximize the detection of early cancers.

As with all of medicine, the likelihood that disease is present is a probability estimate. When a lesion has certain features, there is a high probability of cancer; other features carry a very low or even coincidental risk of cancer, and a great number of findings are intermediate and can be present in both benign and malignant processes. The analysis of findings can be divided into several general categories:

Those that are benign and do not require any intervention

Those that are probably benign and have a very low probability of being malignant, for which follow-up at short intervals is reasonable

Those that are significant when they support or are supported by other indications of cancer

Those that indicate moderate likelihood, should be considered suspicious, and should be biopsied

Those that indicate a high probability of malignancy and require a biopsy

Mammography Is A Screening Test, Not Really A Diagnostic Test

Mammography is unchallenged as a screening test for detecting early-stage breast cancer. No other imaging technique that does not require intravenous contrast agent approaches its ability to find small cancers. Because of the frequent morphologic similarity between benign and malignant lesions, however, mammography is less useful as a diagnostic test where such differentiation is paramount. The safety and low morbidity of a breast biopsy makes it difficult to postpone the biopsy of a lesion when a significant doubt exists. The increasing use of needle biopsy techniques, with their reduced morbidity and expense, permits an aggressive analysis of borderline lesions.

Mammography is not sufficiently accurate to rely on for diagnostic differentiation, although a superficial analysis might suggest the contrary. Mammography appears to be

highly specific in that a negative mammogram in an asymptomatic population of women appears to be extremely accurate. Statistical specificity, however, can be deceiving. Any test can seem to be very good at excluding cancers in a screening population because, despite the fact that breast cancer is very common, it is only diagnosed in a small fraction of the population each year. There are over 200,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States each year. Assuming these occur in the 60 million women over the age of 40, this means that only 1 cancer will be found in every 300 women screened. In other words, if a new test is always read as negative, it will be correct 299 times out of 300, making its specificity 99.6%.

highly specific in that a negative mammogram in an asymptomatic population of women appears to be extremely accurate. Statistical specificity, however, can be deceiving. Any test can seem to be very good at excluding cancers in a screening population because, despite the fact that breast cancer is very common, it is only diagnosed in a small fraction of the population each year. There are over 200,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States each year. Assuming these occur in the 60 million women over the age of 40, this means that only 1 cancer will be found in every 300 women screened. In other words, if a new test is always read as negative, it will be correct 299 times out of 300, making its specificity 99.6%.

Figure 16-1 The classic description of breast cancer is an irregular mass with a spiculated margin. This irregular mass with spiculations was a small invasive ductal carcinoma. |

When the prior probability of cancer is low, the importance of a negative test becomes less meaningful. If an asymptomatic (no signs or symptoms of breast cancer) woman has a negative mammogram, there is a >99% likelihood that she does not have cancer, but this is misleading since, on a purely statistical basis, it is highly unlikely that she would have cancer in the first place. Since only approximately 1 to 5 women among 1,000 develop breast cancer in a given year (depending on their age), a set of 1,000 mammograms could be interpreted as negative without even looking at them, and this would produce an extremely high specificity. Assuming five women would develop cancer among the 1,000, the specificity obtained by interpreting them all as negative would be 99.5% (specificity = the number of mammograms interpreted as negative minus those that actually had cancer, divided by all the women screened = [1,000 – 5/1,000 = 99.5%). In this hypothetical example, the test would have extremely high specificity, but, of course, all of the cancers would have been missed. Statistical measures can be misleading if they are not evaluated in the context in which they were obtained. Even in women who present with a problem (lump, thickening, etc.), the value of the negative mammogram is low. There are those who argue that they use mammography diagnostically in this setting with great success, but they are only deluding themselves. Because the likelihood of cancer is so low, even in women with lumps, in most situations using

a negative mammogram as indicative of no disease is successful simply based on the low probability of cancer being present to begin with, and not the test itself.

a negative mammogram as indicative of no disease is successful simply based on the low probability of cancer being present to begin with, and not the test itself.

The fact that mammography is not truly a diagnostic test does not mean that it is not valuable for evaluation of women who are suspected of having an abnormality. On occasion, a lesion may have highly suspicious characteristics and the mammogram can prompt earlier intervention. It is also useful as a screening test to evaluate the remainder of the breast in question and the contralateral breast in the search for occult disease.

Suspicion Prompting a Biopsy

The quest continues to find a noninvasive test that can reliably differentiate benign lesions from those that are malignant. Because biopsy of the breast is so safe and, if performed properly, so accurate, if a test is to be relied on to avoid a biopsy, it would need to approach near-perfect accuracy for differentiating a benign lesion from one that is malignant to be able to safely avoid a biopsy.

The accuracy of a test is determined by its false-positive (lesions called possible cancers that are not) and false-negative rates (cases called negative where cancer really exists). The thresholds at which intervention (making a tissue diagnosis) is set should be determined by the false-negative rate; false-positive rate; size, stage, and grade of cancers at detection; and ultimately the cost of making the diagnosis (physical and economic). The ideal screening test would not miss any cancers (no false negatives) and have no false positives. Unfortunately, since there is an overlap between the appearance of benign lesions and those that are malignant, the only way to maximize the detection of cancer would be to biopsy anything found by mammography that was not completely normal. This method, however, would result in an unacceptably high false-positive rate. What has evolved is the concept that it is reasonable to follow-up some lesions, and not biopsy them because the likelihood of their being cancer is so low, that biopsy is unreasonable. Sickles’ (1) analysis of lesions that had been classified as probably benign and followed at short intervals has been widely accepted. This review suggested that it is reasonable to follow lesions where the probability that the lesion is a cancer is 2% or less. Consequently, a test that could provide a 98% likelihood that a lesion is not cancer would be reasonable. This approach has become widely accepted despite the fact that there is a very small risk. Of the 17 cancers followed by Sickles that were finally diagnosed, 2 (12%) proved to be stage II when the diagnosis was made. This level of risk has been accepted around the world for probably benign lesions.

Mammography Can Be Diagnostic, But for Only a Few Benign Lesions

Mammography can be diagnostic for several types of benign lesions. For example, those that appear encapsulated, contain fat, and are radiolucent by mammography are virtually always benign and usually represent hamartomas. A densely calcified fibroadenoma is only associated with cancer coincidentally. Intramammary lymph nodes have a characteristic shape and location and need not cause concern unless they increase in size and lose their characteristic shape. Mammography, however, is unable to differentiate, for example, a cyst from a solid lesion, and, although statistically most lesions are benign, mammography can rarely be relied on to make a conclusive diagnosis of a benign process.

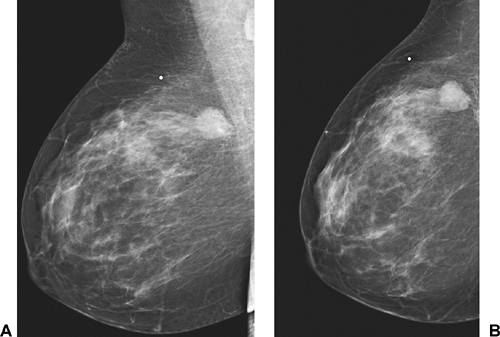

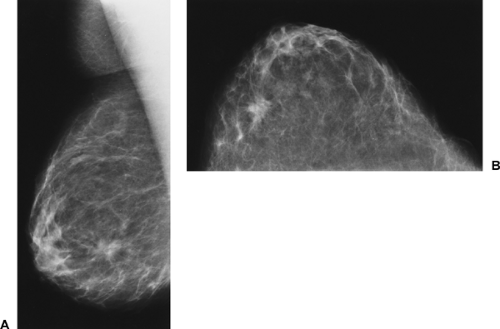

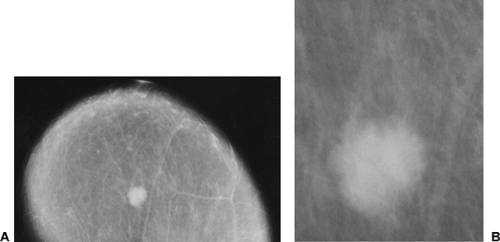

Conversely, mammographic criteria are also frequently insufficient to make an accurate diagnosis of malignancy. For example, most breast cancers are radiographically very dense for their volume, but, as with all signs, this is not a uniform characteristic, and some cancers are relatively low in x-ray attenuation (Fig. 16-3). Round or oval lesions

with smooth, sharply defined margins are usually benign, but some cancers appear smoothly marginated (Fig. 16-4).

with smooth, sharply defined margins are usually benign, but some cancers appear smoothly marginated (Fig. 16-4).

Despite the lack of specificity for particular lesions, criteria have evolved that should alert the radiologist to the possibility of malignancy. Although many of these signs are not definitive because they overlap significantly and are often exhibited by benign processes, and although mammography frequently cannot be relied on to differentiate benign from malignant lesions, when certain morphologic criteria are present, mammography can be extremely accurate.

Age and Probability of Cancer

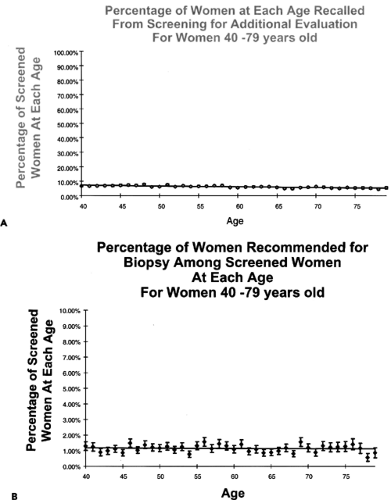

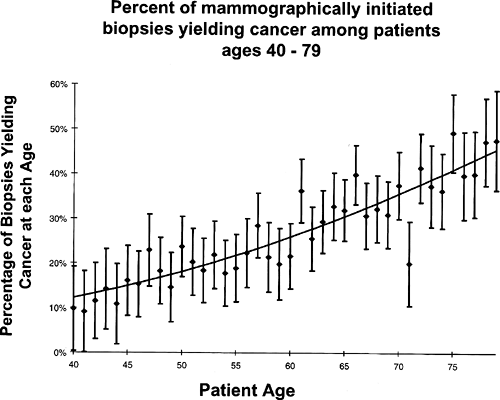

We reviewed the biopsy results for lesions detected at screening that were clinically occult and biopsied only on mammographic suspicion. The percentage of women recommended for biopsy at each year of age from 40 years to 79 years was 1% to 2% of the women screened at that age (2) (Fig. 16-5). The yield of cancer, however, increased steadily with increasing age beginning with a positive predictive value (cancers diagnosed divided by biopsies performed) of approximately 15% at 40 years to almost 50% by 79 years (Fig. 16-6). This increase is not surprising given that the prior probability of cancer (cancers available to be detected) increases steadily with increasing age. These results suggest that there are similar findings at each age that might indicate malignancy, but the likelihood that they represent cancer increases with increasing age.

Findings That Raise the Possibility of Malignancy

Cancer usually appears on a mammogram as a mass, architectural distortion, or cluster of pleomorphic calcifications. The majority of these, however, are benign, and the radiologist must separate these from lesions that have the possibility of being cancer. Table 16-1 is a list of findings that should raise varying degrees of concern.

Neodensity or New Calcifications

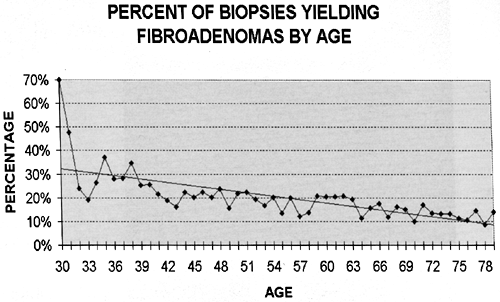

The breast is a fairly stable organ that does not change dramatically from year to year except with weight fluctuations (since it is a repository of fat). Cysts may come and go, but these are found in a minority of women. Fibroadenomas likely originate when the breast is developing, and, although possible, it is unusual for a fibroadenoma to suddenly appear. In a review of the percentage of biopsies relative

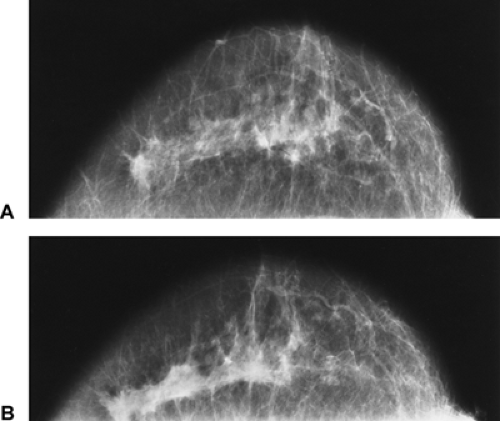

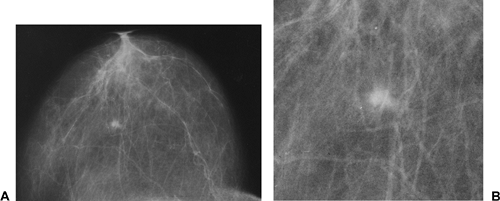

to age that proved to be fibroadenomas, there is a rapid decrease with increasing age (Fig. 16-7). Since the breast tissues of many women from age 30 years and older are likely to be undergoing involutional changes, it is very uncommon for normal fibroglandular breast tissue to suddenly appear. A small percentage of women who are on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may develop new breast tissue densities, but even this is uncommon. In an unpublished blinded study, we found that only approximately 13% of women who began to use HRT had any noticeable change on their mammogram. For these reasons, a new density on a mammogram should be viewed with suspicion (Fig. 16-8), and, unless the new density can be directly linked to the use of hormones, diagnostic evaluation is usually indicated.

to age that proved to be fibroadenomas, there is a rapid decrease with increasing age (Fig. 16-7). Since the breast tissues of many women from age 30 years and older are likely to be undergoing involutional changes, it is very uncommon for normal fibroglandular breast tissue to suddenly appear. A small percentage of women who are on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may develop new breast tissue densities, but even this is uncommon. In an unpublished blinded study, we found that only approximately 13% of women who began to use HRT had any noticeable change on their mammogram. For these reasons, a new density on a mammogram should be viewed with suspicion (Fig. 16-8), and, unless the new density can be directly linked to the use of hormones, diagnostic evaluation is usually indicated.

TABLE 16-1 MAMMOGRAPHIC FINDINGS THAT RAISE THE POSSIBILITY OF MALIGNANCY | |

|---|---|

|

Benign breast calcifications, on the other hand, commonly develop with increasing age. The vast majority of calcifications are due to benign processes. When new calcifications develop in clusters, however, they should be carefully evaluated to determine whether they should arouse concern.

Findings That Suggest a High Probability of Malignancy

Spiculated Lesion

A dense, irregular mass with a spiculated margin that is not related to prior surgery is one of two combinations of

features that is virtually diagnostic of malignancy (Fig. 16-9). Strands of fibromalignant tissues radiating out from an ill-defined mass, producing a spiculated appearance, can be considered virtually pathognomonic of breast cancer, because very few benign lesions produce a similar appearance. The spicules may extend more than several centimeters from the main tumor mass or appear as a fine “brush border” (Fig. 16-10). They may be easily visible when the cancer is surrounded by fat or barely perceptible when the tumor grows in dense fibroglandular tissue (Fig. 16-11). The spiculations represent fibrosis that is probably related to the generalized desmoplastic response that many cancers elicit in the surrounding tissue. On occasion, only fibrosis is seen on microscopic examination of these extensions,

but careful evaluation usually reveals tumor cells intimately associated with the spicules and probably stimulating the fibrotic process.

features that is virtually diagnostic of malignancy (Fig. 16-9). Strands of fibromalignant tissues radiating out from an ill-defined mass, producing a spiculated appearance, can be considered virtually pathognomonic of breast cancer, because very few benign lesions produce a similar appearance. The spicules may extend more than several centimeters from the main tumor mass or appear as a fine “brush border” (Fig. 16-10). They may be easily visible when the cancer is surrounded by fat or barely perceptible when the tumor grows in dense fibroglandular tissue (Fig. 16-11). The spiculations represent fibrosis that is probably related to the generalized desmoplastic response that many cancers elicit in the surrounding tissue. On occasion, only fibrosis is seen on microscopic examination of these extensions,

but careful evaluation usually reveals tumor cells intimately associated with the spicules and probably stimulating the fibrotic process.

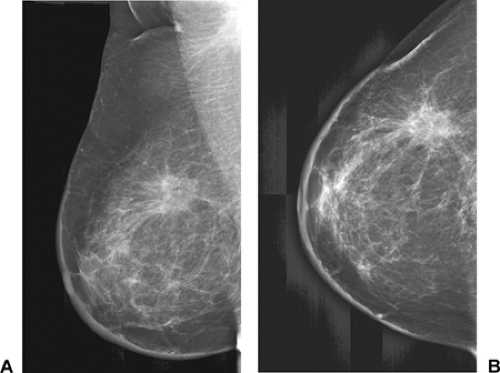

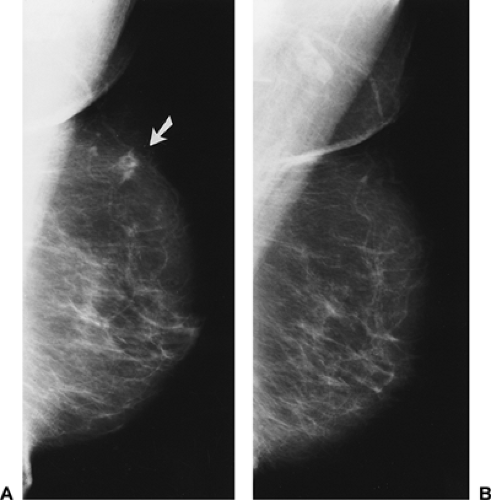

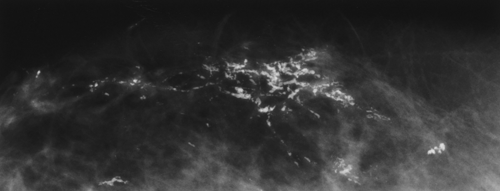

Figure 16-8 Neodensity. (A) The density in the upper left breast (arrow) developed since the previous mammogram (B). It proved malignant at biopsy. |

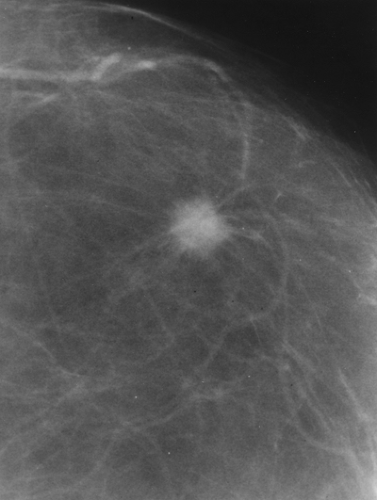

Figure 16-9 A spiculated mass that is unrelated to surgery is almost certain to be malignant. The appearance of this 1-cm invasive breast cancer is virtually pathognomonic. |

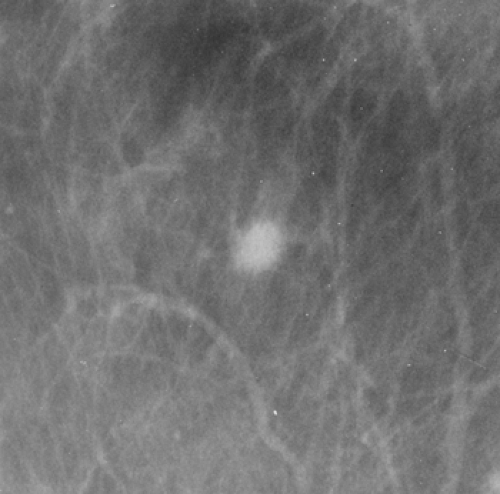

Figure 16-10 The very fine spiculations associated with cancer may produce a “brush border,” which causes the ill-defined border of this invasive breast cancer. |

A lesion with spiculated margins should be considered malignant even if it remains unchanged over time. Although rare, invasive cancers may remain unchanged on mammography for as long as 5 years (3). It is likely that cancer growth is a discontinuous process, fluctuating over time. Some lesions may exhibit slow or no growth and then suddenly accelerate their growth. A spiculated lesion that remains stable over time (up to 5 years) but cannot be explained by postsurgical change should still be considered suspicious and should be biopsied.

Major Mimics of Breast Cancer

Postsurgical scarring, fat necrosis, radial scars (idiopathic lesions also called elastosis or indurative mastopathy), and extremely unusual tumors, such as extra-abdominal desmoid lesions and granular cell tumors, may have spiculated margins that mimic those of malignancy. With the exception of radial and postsurgical scars, these other lesions are extremely rare, and a spiculated mass that is not clearly a scar should be biopsied.

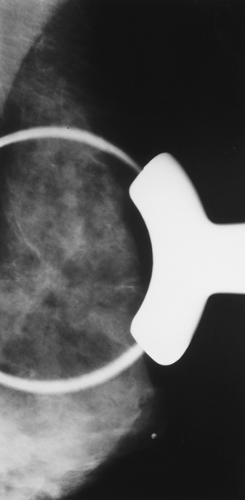

Differentiation of a Postsurgical Scar from Breast Cancer

A postsurgical scar rarely raises significant concern. After a biopsy with benign results, the breast usually heals within 12 to 18 months, with little or no visible evidence of the previous surgery on the mammogram (4). On occasion, particularly if the mammogram is obtained within 1 year of the surgery, the architecture may be distorted and spiculation may be present (Fig. 16-12). Postsurgical change will almost always resolve or greatly diminish over the subsequent 6 to 12 months when the surgery has occurred for a benign process.

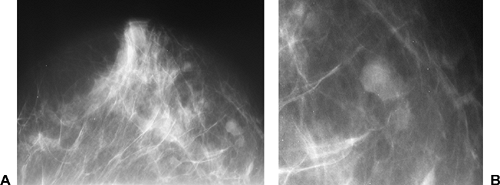

If the postsurgical nature of the distortion is not immediately clear, several observations can increase the confidence in the diagnosis. Postsurgical change frequently looks very different between the lateral and craniocaudal projections (Fig. 16-13). A postsurgical scar often appears spiculated in one projection and difficult to see in the other. Although there are occasional exceptions, cancer almost always looks worrisome regardless of the projection and, as a three-dimensional mass, similar in appearance on both projections.

On rare occasions, fat necrosis can look like a malignancy (Fig. 16-14). If there is a clear, encapsulated, lucent structure at the center of the spiculation, benign fat necrosis is the reliable diagnosis.

Markers can be placed on the cutaneous scar to relate the incision to the underlying distortion in postsurgical change, but this may be misleading because the tissue that is removed at biopsy and the subsequent postsurgical change is usually deeper in the breast and at a distance

from the skin incision. If there is a question, review of the preoperative mammograms, if available, provides a better comparison of the location of the distorted architecture with the location of the benign lesion as it appeared before its excision.

from the skin incision. If there is a question, review of the preoperative mammograms, if available, provides a better comparison of the location of the distorted architecture with the location of the benign lesion as it appeared before its excision.

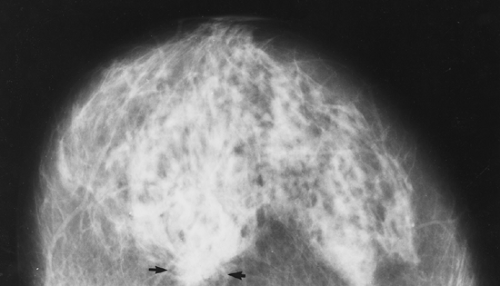

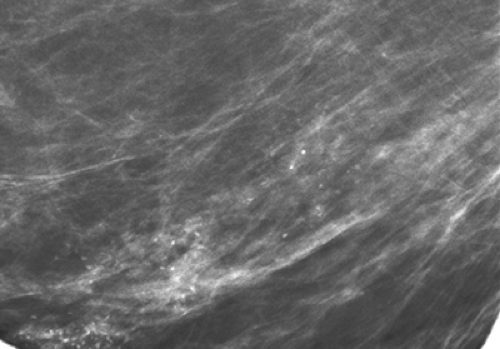

Figure 16-11 Cancer (arrows) may be hidden in dense fibroglandular tissue, as in this craniocaudal mammogram. |

A review of the pathology of the removed tissues can increase the confidence that the spiculated change is merely postsurgical. It is highly improbable that a sizable cancer would develop over a 1-year period in the exact same area as a benign biopsy with no clue to its presence in the excised tissue. If there is any remaining question, the pathology should be reviewed to be certain there is no suggestion that the tissue removed might have been at the edge of a cancer that was missed at surgery. We have seen three cases in which the biopsy revealed atypical hyperplasia, and a progressive increase in calcifications in the region of the biopsy led to a re-excision that revealed intraductal cancer. This is unusual and probably related to the uncertainty that may exist in differentiating atypical hyperplasia from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), but a high index of suspicion is reasonable when the biopsy reveals atypia and it is not clear that the lesion has been completely excised.

It is well established that the results of a needle biopsy should be reviewed and compared to the imaging findings to be certain that there is concordance between the two. If the imaging suggests probable malignancy and the biopsy is benign, then surgical removal is indicated. Similarly, it is also important to remember that surgery may miss a visible or palpable cancer. If the mammogram preceding the biopsy revealed a very suspicious lesion and the surgical biopsy result was benign, it is possible that the cancer was missed at the clinically guided biopsy (5). An early (2 to 3 weeks after operation) follow-up mammogram can determine whether the lesion seen by mammography was excised and whether re-excision is indicated.

Radial Scars

The radial scar is a fairly common benign lesion, characterized by often dramatic spiculation that is very similar to that produced by cancer. Because of its name, it is still confused by some with postsurgical change. They are, in fact, different lesions. The radial scar is idiopathic and unrelated to known trauma. It represents a scarring process, but its etiology remains unknown. This lesion is commonly found by the pathologist reviewing breast tissue at the microscopic level. As an increasing number of women are screened, more of the larger radial scars are being found by mammography. Their appearance is indistinguishable from malignancy. They frequently have long spicules that are conspicuous because they trap fat. They often lack a radiographically visible central mass (Fig. 16-15). Although the diagnosis can be suggested by these characteristics, their mammographic morphology is not sufficiently distinctive to permit them to be reliably differentiated from cancer, and they should be biopsied to make a secure diagnosis. Some believe that a vacuum-assisted needle biopsy is a reliable method of diagnosing these lesions. We prefer surgical excision. The number of radial scars that are biopsied is still relatively small, so that the biopsy of those detected by mammography represents a small percentage of breast biopsies. Furthermore, excisional biopsy provides a more reliable diagnosis, with a lower risk of sampling error than needle biopsy.

Calcifications Associated with a High Probability of Malignancy

The second lesion that is almost always due to breast cancer is the lesion that produces pleomorphic, fine, linear branching calcifications (Fig. 16-16). A wide variety of calcifications are demonstrated by mammography. Although the vast majority of calcifications are associated with benign processes, there are some patterns that are almost always due to cancer. The pattern of calcium deposition that is usually associated with comedonecrosis (central necrosis of cancer filling the center of a duct and calcifying) in high-grade intraductal cancer is virtually diagnostic. Fine, linear, irregular branching calcifications are practically always due

to malignancy (Fig. 16-17). Segmental, or even more extensive, calcifications that are extremely pleomorphic are virtually always due to extensive cancer, but these are, fortunately, not very common (Fig. 16-18).

to malignancy (Fig. 16-17). Segmental, or even more extensive, calcifications that are extremely pleomorphic are virtually always due to extensive cancer, but these are, fortunately, not very common (Fig. 16-18).

Findings That Should Arouse Suspicion

Other findings on mammography have a significant probability of being due to cancer, although many will prove to be benign. Spiculation of a mass or fine, linear, branching calcifications are the only signs that virtually always indicate cancer. All other signs can be found in association with benign lesions as well, and thus are considered suspicious. Nevertheless, suspicious findings carry a significant enough risk to warrant intervention.

Figure 16-17 Irregular, linear calcifications in a segmental distribution virtually guarantee malignancy. These proved to be high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ with comedonecrosis. |

Figure 16-18 Most breast cancers detected in screening programs are small. These segmentally distributed calcifications proved to be due to fairly extensive ductal carcinoma in situ. |

Lesions with Ill-Defined Margins

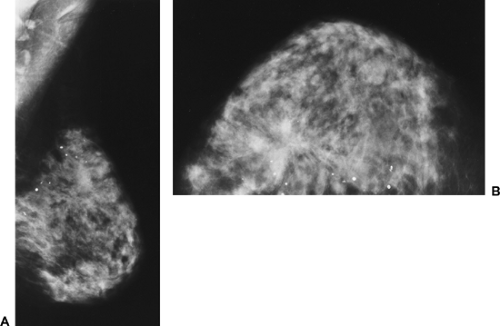

Ill definition of the margins of a lesion is a common, though nonspecific, characteristic that suggests a malignant process. Ill-defined margins are often due to superimposed normal breast tissues obscuring the margins of a lesion. With the introduction of DBT, more cancers will be found to have spiculated margins. Nevertheless, there will still be those that are simply ill-defined masses. Cancer should be considered when a three-dimensionally real volume of tissue with increased density is found whose borders are poorly demarcated from the surrounding tissue (Fig. 16-19).

Many cancers do not elicit the desmoplasia that produces spiculations, but even in these cases tumor infiltration generally is reflected in the lack of a mammographically well-defined border of the tumor as it invades the surrounding tissue.

Many cancers do not elicit the desmoplasia that produces spiculations, but even in these cases tumor infiltration generally is reflected in the lack of a mammographically well-defined border of the tumor as it invades the surrounding tissue.

A lesion with ill-defined margins may rarely present as a diffuse process over a large area and should be distinguished from asymmetric tissue density that is merely the accentuation of normal breast tissue. When any tumor (benign or malignant) is surrounded by dense normal fibro-glandular tissue, the distinction between an invasive margin and one that is merely obscured by normal tissue becomes difficult or not possible to make. This distinction will be easier to make with tomosynthesis, but even with cross-sectional imaging cancers and benign lesions can blend with the abutting tissue. If normal breast architecture is preserved and there are no significant, associated calcifications and no architectural distortion, an area of asymmetry is consistent with asymmetric breast tissue. If, however, the asymmetry corresponds to a palpable asymmetry, the area should be viewed with suspicion. If a focal area is palpable and contains no fluid on aspiration or represents a solid mass by sonography, biopsy should be considered. Increasing x-ray attenuation of an area of asymmetry over time is also a concern (Fig. 16-20).

Although some rare cancers do, breast cancer rarely contains fat. On rare occasions, we have seen cancers form a horseshoe configuration and appear to partially surround fat, but this is uncommon. Cancers are usually higher in attenuation centrally, with the density fading toward the periphery of the lesion. When this pattern is associated with distortion of the breast architecture, the probability of malignancy is increased (Fig. 16-21). Cancer generally has higher x-ray attenuation than the same volume of fibroglandular tissue (Fig. 16-22), which is a clue to the diagnosis. However, it is not unusual for a malignant lesion to be subtle and not cause increased attenuation (Fig. 16-23). Some cancers, particularly the colloid subtypes, have even lower attenuation than an equal volume of fibroglandular tissue, but these are unusual.

Lesions with a Microlobulated Margin

Many well-circumscribed lesions within the breast have a degree of lobulation. Fibroadenomas, for example, are frequently

not perfectly round and smooth but have undulating, lobulated margins. The more lobulated the lesion, however, the more likely it is to be malignant (Fig. 16-24). When the lobulations are multiple and measure only several millimeters or smaller, the degree of suspicion should increase. In the past, some have used the term knobby to describe these very small lobulations, but the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) suggests the term microlobulation. It is a strong indication of cancer but, once again, not pathognomonic, because benign masses can have similar margins.

not perfectly round and smooth but have undulating, lobulated margins. The more lobulated the lesion, however, the more likely it is to be malignant (Fig. 16-24). When the lobulations are multiple and measure only several millimeters or smaller, the degree of suspicion should increase. In the past, some have used the term knobby to describe these very small lobulations, but the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) suggests the term microlobulation. It is a strong indication of cancer but, once again, not pathognomonic, because benign masses can have similar margins.

Architectural Distortion

Breast cancer does not always produce a mammographically visible mass, but it frequently disrupts the normal tissues in which it develops. This distortion of the architecture may be the only visible evidence of the malignant process. This is an important, but often very subtle, manifestation of breast cancer. In general, the flow of structures within the breast is uniform and directed toward the nipple, along duct lines. On occasion, a malignant process will produce a cicatrization of tissue, pulling in the surrounding elements toward a point that is eccentric from the nipple (Fig. 16-25).

Although architectural distortion should be regarded with a high degree of suspicion and biopsy is indicated, there are also benign causes of architectural distortion.

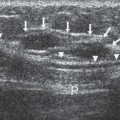

Postsurgical scarring (Fig. 16-26) and fat necrosis are the most common nonmalignant causes, although it is surprisingly uncommon for the breast to form a permanent, radiographically noticeable, scar (in spite of palpable scarring). Unless architectural distortion clearly coincides with a region of previous surgery, it should be investigated. In our experience, architectural distortion that is seen on two dimensional mammography is found to have a mass on DBT.

Postsurgical scarring (Fig. 16-26) and fat necrosis are the most common nonmalignant causes, although it is surprisingly uncommon for the breast to form a permanent, radiographically noticeable, scar (in spite of palpable scarring). Unless architectural distortion clearly coincides with a region of previous surgery, it should be investigated. In our experience, architectural distortion that is seen on two dimensional mammography is found to have a mass on DBT.

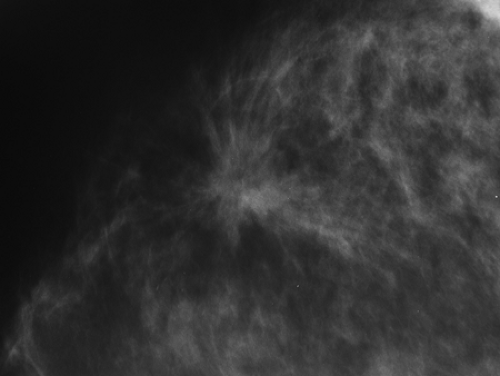

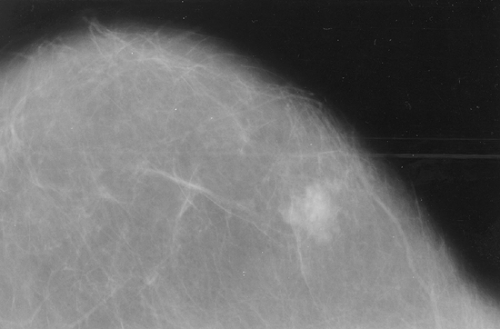

Figure 16-23 Cancer is not always highly attenuating. This invasive cancer is not very dense for its size, as seen on this craniocaudal projection. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree