The Breast Imaging Report: Data Management and the Breast Imaging Audit

The accurate and clear communication of breast imaging results to the patient and her physician become a major issue in the 1980s. Although the communication of results from all imaging studies is important, because of the high visibility and public concern over breast cancer and mammographic screening, and the fact that mammography, unlike most other imaging studies, is principally used in asymptomatic, healthy individuals, attention has been focused on these communications.

The Push for Immediate Interpretation

There has been a great deal of emphasis on providing women with immediate reports on their mammograms. This is probably not a good idea. The medical reality is that mammography is essentially a Papanicolaou (Pap) smear of the breast. The issues surrounding breast cancer screening are identical to those surrounding screening for cancer of the uterine cervix. Both tests are designed to evaluate healthy individuals in the search for a cancer that is common but still only affects a relatively small number of individuals each year. Although it is a common malignancy, the vast majority of women will not have breast cancer in a given year or even a lifetime. The mammography screening effort is designed to find the few women (1 to 5 per 1,000) who do have breast cancer each year.

Although the medical realities are similar (both mammography and cervical testing have a fairly high recall rate of approximately 10%, with most recalls ultimately being false positives), the psychological issues surrounding breast malignancies appear to differ dramatically from any other cancer. Even though lung cancer kills more women each year, and despite the fact that most women who are diagnosed with breast cancer do not die from it, breast cancer evokes greater emotions than virtually any other malignancy. There are significant anxieties associated with just having a mammogram and even higher anxieties associated when suspicion is raised, and very high anxiety occurs when cancer is detected. Women apparently accept the fact that it may take weeks to learn the result of their Pap test, but waiting several days for the result of a mammogram is almost intolerable for some women.

A number of years ago, a television exposé revealed a practice where women who had cancers seen on their mammograms were not informed by the radiologist, and they did not hear from their own doctors. Thinking “no news is good news,” they assumed that everything was alright. Consequently, their diagnosis was delayed. As a result the expose urged women to be sure that they received their screening report before they left the screening center. Other centers, as a public relations maneuver, publicized the fact that they were willing to provide immediate interpretations of their screening studies. Unfortunately, these, in conjunction with the media stories urging women to require immediate analysis, brought great pressure to bear on many centers to read screening mammograms online. The pressure continues today, despite the fact that this is probably not the best idea from a medical perspective.

Online Reading Is Not a Good Idea

Despite the psychological issues, from a scientific and medical perspective, reading online is probably not a good idea. A number of years ago we performed a study to evaluate the use of double reading in reducing the false-negative rate of mammography. We had a main reader read the mammograms slowly and methodically, and then had a second reader quickly review the cases, looking for cancers that the first reader might have missed. In a study of several thousand women, 39 cancers were detected on the screening mammograms. The first reader was slow and methodical and took over an hour to read 40 mammograms set up on a multiviewer. The second reader then rapidly reviewed the same studies spending only a few minutes looking at the same cases. The second reader detected 3 cancers that were missed by the main reader, confirming the fact that cancers can be overlooked by even a slow and methodical review. Although the second reader found cancers missed by the first reader, the second reader, who went very quickly, not surprisingly missed 8 cancers that had been detected by the main reader. This study not only confirmed the value of double reading, but it illustrated the fact that rushing the interpretation of a screening mammogram increases the chances of overlooking a cancer.

For a period of time, based on complaints from some of our patients, our administration insisted that we provide immediate reports for screening studies. This produced a new stress: some women would grow impatient in the waiting room while they awaited their results. Their impatience was conveyed to the technologists who then conveyed it to the radiologists who felt pressured to read the studies quickly. Forcing us to read online also complicated our effort to provide a second reading by a staff radiologist, which we showed consistently increased our cancer detection rate by 3% to 5%. Since double reading is not reimbursed and we were providing this as a free service, it needed to be done efficiently, and providing an immediate interpretation made it much less efficient to also provide a second reading. Fortunately, reason prevailed, and we no longer provide immediate interpretations of screening studies and have been able to double-read our studies efficiently. Spending the time to detect as many cancers as early as possible is far more important than providing an immediate interpretation when the latter increases the chance that the interpretation will be falsely negative.

Mammography Is Not Performed to Tell Someone She Does Not Have Cancer

It has been my experience that many, if not most, women have a mammogram to reassure themselves that they do not have breast cancer. The desire for an immediate interpretation is the need to learn as quickly as possible that they do not have this dreaded malignancy. Unfortunately, what many women fail to understand is that, even though their mammogram is negative, unfortunately, this does not guarantee that they do not have breast cancer. A significant number of women who have cancer have a negative mammogram. Thus, the desire for an immediate report is based on false assumptions. The fact that a woman can have a negative mammogram and still have breast cancer means that a negative mammogram should not be reassuring. The reason for doing the mammogram is to try to find some cancers earlier. The effort should be directed toward this goal. The goal of mammography is not to provide a woman with rapid and potentially false reassurance. There should be no urgency to find out that the mammogram is negative. The time should be spent trying to find the cancers that can be detected earlier by mammography. It is well established that mammography misses 5% to 15% of cancers that are present and palpable at the time of a screening. What is frequently forgotten or not appreciated is that as many as an additional 20% of cancers become clinically evident within 1 year of a negative mammogram (1). Mammography cannot tell a woman that she does not have breast cancer. The only benefit from mammography is the potential to detect cancers earlier. The process of mammographic review should be to maximize the detection of small cancers and not to be rushed to provide immediate, and potentially false, reassurance.

Women will be denied access to screening if the costs are not kept low. The best way to keep the cost low and increase the likelihood of detecting cancer earlier is to have screening centers where the resources are used to obtain high-quality images in a cost-effective manner. This generally means that the radiologist is off-site, where his or her time can be managed more efficiently through batch interpretation of films. This may delay the interpretation, but it permits a less hurried review of the images and offers the opportunity to provide cost-effective double reading. Furthermore, radiologists who interpret mammograms are under a great deal of stress when interpreting these studies. Many are leaving the field, or unwilling to interpret mammograms because of this stress (2) and concerns over the high risk of being accused of negligence for the failure to diagnose breast cancer. The death rate from breast cancer declined by 25% in the decade of the 1990s, in large part due to screening. Radiologists should be encouraged to continue to provide this service. If they are driven from the field, then the benefit will be lost. Forcing radiologists to read online increases their stress. It decreases the chance that the practice will be able to provide free double-reading. Since a negative mammogram does not exclude cancer, rushing to provide false reassurance makes no sense. Online reading should be discouraged.

General Principles for Reporting Breast Imaging Studies

Analysis of the mammogram should be clear and concise. Conclusions should be decision oriented and provide guidance, when appropriate, for the next course of action.

Mammography Is Primarily a Screening Technique

When a lesion is detected, it is usually no more than an educated guess as to its true histology. The reader must decide whether it has a significant probability of malignancy and whether a biopsy is indicated. Some radiologists try to speculate on the histology of a finding. This speculation contributes little to overall management. Unless pathognomonic signs are present, cysts, fibroadenomas, metastatic lesions, primary breast cancers, and other pathologic processes may have identical mammographic appearances. The differentiation of benign lesions from malignant is greatly improved using digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), but, until the accuracy of the technique has been proved in large studies, the radiologist should continue to use descriptive terminology rather than attempt to define true histology. Some believe that they can distinguish benign lesions from malignant ones, but it is not clear that this is the case, and it only applies to a limited number of benign lesions that have all of the benign features.

Mammography is an excellent technique for finding small masses or microcalcifications in the breast, many of which prove to be malignant or associated with malignancy. Mammography, however, is poor at determining which of these is benign and which is malignant, so attempting to make a histological determination based on the imaging findings is of little value. The interpreter should be well aware of this and choose appropriate descriptive terms and summary assessments. It serves no useful purpose and, in fact, may be misleading to overinterpret breast imaging studies.

Because there is a significant overlap in the appearance of varying histologies in the breast, including those that are benign and those that are malignant, it is preferable to describe findings using appropriate imaging terms. There is no good support for the belief that histology can be accurately inferred from the mammogram, with the exception of benign, pathognomonic lesions such as intramammary lymph nodes, calcified fibroadenomas, vascular calcifications, and the fat-containing lesions. The terms fibrocystic disease, fibrocystic changes, fibrocystic tissues, dysplasia, and hyperplasia are inappropriate for imaging descriptions and should be eliminated from imaging interpretations. Histopathologic terms should be reserved for the pathologist and should be avoided in the clinical evaluation.

Similarly, when a physical examination is performed, the terminology should be appropriate for that test. Stating that a woman with lumpy breasts or mammographically dense tissue has fibrocystic disease does little more than frighten the patient and create the unsubstantiated prejudice that she is more likely to develop breast cancer. This may unfairly influence recommendations for management, and, from a practical point of view, it may even affect health insurance premiums. Many, if not most, normal breasts are lumpy by their design. Women and physicians should be educated to this fact and should be taught to look for new lumps. To call a lumpy breast fibrocystic is grossly inaccurate. In fact, in breasts that are lumpy, there may be little fibrosis and no cysts (Fig. 25-1). The normal breast is a heterogeneous organ with varying tissue composition, and many breasts feel extremely heterogeneous on clinical examination. This is what should be described in these terms, but most examiners cannot tell a lumpy breast that is composed almost exclusively of fat from one that actually contains a great deal of fibrous tissue and even numerous, nondistended, cysts.

Radiographically, breasts are as varied as are individual facial features. There is a broad spectrum of tissue patterns found on mammograms that are determined by the relative concentrations of the various tissue types in a given individual. In 1976 John Wolfe described four basic breast tissue patterns evident by mammography, and he expressed his belief that they were associated with varying risks for the development of breast cancer (3). The experienced radiologist knows very well that these patterns are a gross oversimplification. We once tried to develop even more refined comparative patterns and gave up at 46! Arguments followed over the accuracy of Wolfe’s observations with regard to cancer risk. Boyd has spent years studying the relationship of mammographically determined patterns and cancer risk and has concluded that women with dense tissue patterns had 1.8 to 8 times the risk of developing breast cancers as do women with fatty patterns (4,5). This has raised many research questions, but it is not, at this time, of any clinical value since breast cancer is fairly common among women, regardless of their tissue patterns.

It is well established that, although many cancers are detected by mammography among women with dense breast tissues, the denser patterns can hide some cancers. Since there is not yet a practical way to apply tissue patterns in advising women based on risk, most radiologists ignore the risk associated with various patterns but indicate the tissue pattern as a measure of the possible reduction in sensitivity for an individual case. Since dense tissue patterns can obscure a breast cancer, the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends that the breast imaging report provide a measure of the density of the breast, as an indication of the sensitivity of mammography for the patient.

Wolfe’s system was succinct, and a similar system has been adopted by the ACR in the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS). As with clinical examination, there is a broad spectrum of radiographic appearances of breast tissue, and, based on our current level of knowledge, it is impossible to determine which of these patterns are normal and which represent significant pathologic changes. Consequently, the four patterns are all considered normal. The mammographic report should contain only findings that are of significance in patient management and that reflect the level of sensitivity for detecting small cancers that mammography has in a given individual. At the current level of understanding, overall radiographic density is significant only for the fact that small cancers are harder to detect in the dense breast.

Birads: The American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

The importance of high-quality mammography has been established and federally mandated in the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) of 1994. A component of quality is the clear and concise transmission of the results of the interpretation of the mammogram. Recognizing the need to provide clear and accurate reports, the ACR developed BIRADS. Originally developed for screening mammography, BIRADS has now been extended to include ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast (BIRADS-US and BIRADS-MRI) (1). The rationale behind the development of these systems is to reduce confusion and increase the clarity of breast imaging reports, and to develop a common language so that data can be pooled and image interpretation refined.

The ACR approach encourages the use of a standard language for reporting these studies and a framework for the breast imaging report. BIRADS urges a concise and clear description of findings (6), with a decision-oriented final assessment that provides guidance for future care. Conveying important medical information is actually quite difficult. There is a great deal of debate as to what constitutes a clear imaging report. Some feel that they should provide extensive descriptions with a list of pertinent negatives as well as the positive findings. Others feel that the report should be telegraphic with just the conclusions provided, and there is a wide spectrum in between. BIRADS was developed to try to reduce the complexity and confusion of the breast imaging report by constraining the language and providing a dictionary of terms known as the lexicon (which I suggested as a fancy name for a dictionary), so that the use of the words would have the same meaning in all reports. It provides a report outline to try to reduce the long, confusing, and often rambling reports of the past, and it requires that the radiologist make an interpretive decision that clearly indicates what, if any, additional evaluation is needed, based on the imaging findings.

Since the early detection of breast cancer is the primary reason for imaging the breast and mammography is the only technology that has been shown to be efficacious for screening, BIRADS-Mammography remains the most important component of BIRADS. The US and MRI modules are becoming increasingly important, but as the newest components they will likely undergo some significant changes over the next several years, as the use of both technologies evolves. It is for this reason that this chapter will concentrate on the mammography report, with some attention to US and MRI.

BIRADS for mammography encourages a decision-oriented image review and requires that each mammography report fit into 1 of 7 final report categories (a change from the original 6 categories). These final assessment categories have also been adopted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as required summaries for each mammography report under the MQSA (the FDA requires a final assessment summary at the end of each report). The goal of BIRADS is to standardize breast imaging interpretation so that reports are clear, understandable, and decisive (with unambiguous guidance for the next step, if one is indicated). Not only is BIRADS a good idea for providing clear,

unambiguous reports, but if all groups collect data in a standardized fashion, then the data can be pooled to permit greater statistical power and perhaps greater insight into the breast cancer screening effort.

unambiguous reports, but if all groups collect data in a standardized fashion, then the data can be pooled to permit greater statistical power and perhaps greater insight into the breast cancer screening effort.

The History of BIRADS

A wide variation in mammographic quality in the United States, demonstrated by the FDA’s Nationwide Evaluation of X-Ray Trends study in 1985 (7,8), and an interest on the part of the American Cancer Society (ACS) to designate sites for the ACS National Breast Cancer Awareness Screening Programs, as well as a desire on the part of the ACR to encourage quality mammography and mammography reporting, led to the development of the ACR’s Mammography Accreditation Program in 1986 (9). This program was initially voluntary and established a process for the certification of mammographic equipment; training requirements for radiologists, technologists, and medical physicists; and maintenance of rigorous quality control measures. This process was eventually adopted by the FDA under the MQSA, and accreditation has become a requirement for all mammography facilities.

The ACR recognized that part of a strong quality assurance program was the accurate formulation and communication of the mammography interpretation. Concerns had been raised by medical organizations. such as the American Medical Association (10), that mammography reports were often ambiguous and interpretation was indecisive, leaving the referring physician in a quandary as to what to do. Much of the problem was due to the lack of a universally accepted set of descriptive terms and a structured, decision-oriented reporting system.

As a quality assurance measure, the Breast Task Force of the ACR appointed a committee of experts in breast imaging to develop standardized mammographic terminology and an organized reporting system, in an effort to reduce confusing breast imaging interpretations. In addition, although screening services had proliferated, the diversity of health care delivery in the United States and the lack of comprehensive databases had made it difficult to assess the effect of screening nationally to help determine where improvements could be made. Consequently, an additional goal of the ACR committee was to develop a database that would permit pooling of screening results from across the United States to facilitate outcome monitoring. The overall goal was to improve the quality of breast cancer screening.

Primarily composed of experts in mammography, the committee that developed the ACR’s BIRADS was a cooperative effort, with assistance and input from several groups, including representatives of the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control, the FDA, the American Medical Association, the American College of Surgeons, the College of American Pathologists, and other ACR committees. Such a broad base of support insured that the system would be adopted nationwide.

BIRADS Is Born

BIRADS was originally based on, and adapted from, the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Reporting System (11) which I had developed, along with a lesion-analysis approach that was developed by Carl D’Orsi et al (12) in conjunction with Bolt, Beranek, and Newman. BIRADS was conceived as a system that would evolve over time as new data emerged, permitting refinements of the system, and has now undergone several revisions. Below is a summary of the BIRADS approach. The reader is cautioned that the following does not constitute an official copy of the system. Although I am a member of the ACR BIRADS committee, I disagree with several of the more recent modifications to the system. These, and the reasons for disagreement, will be provided. The reader is encouraged to contact the ACR to obtain the latest copy of BIRADS or to go to the ACR website (http://www.acr.org/).

The BIRADS guide for mammography is composed of six major sections:

Introduction

The breast imaging lexicon (dictionary)

The reporting system itself

A section on follow-up and outcome monitoring

A guidance chapter to further explain the rationale behind parts of the system

A data collection chapter

Appendices with various data collection forms

The introduction to BIRADS provides general principles in breast cancer detection and diagnosis. It establishes the differences between screening (the evaluation of asymptomatic patients in the search for unsuspected cancers) and diagnostic evaluation (symptomatic patients requiring additional evaluation because of an abnormal screening study). Not only is BIRADS important for radiologists, but the distinctions between these functions and their definitions are important for all physicians to understand. The introduction emphasizes the need for coordinated breast care and defines the role of imaging in that care.

Screening

It is stated that the major role for mammography is the earlier detection of breast cancer in asymptomatic women. Although mammography can detect the majority of breast cancers, there are some that are palpable yet elude mammographic detection (13). BIRADS reinforces the fact that physical examination remains an important component of screening. In addition, although mortality reduction has not been objectively shown, breast self-examination is encouraged in the document.

Breast Evaluation (Diagnostic Imaging)

Although mammography is primarily a screening technology, when it is used in conjunction with other breast imaging techniques, such as sonography, it may be helpful in the evaluation of women who have a sign or symptom that suggests breast cancer. BIRADS clearly states that breast cancer cannot be excluded on the basis of mammographic evaluation. Just as management decisions must be made on the basis of abnormal mammographic findings among women with normal findings on clinical examination, there are many decisions that must be based on the clinical evaluation when the mammogram is negative.

Although some legal sources suggest that disclaimers will not protect a radiologist from a lawsuit, statements indicating the somewhat lower sensitivity of mammography in the dense breast or suggesting the further disposition of a clinical finding with normal mammographic findings may be added, as a source of information to the clinician. Although BIRADS acknowledges the fact, even without BIRADS it has long been established that mammography does not demonstrate all breast cancers and that the clinician should pursue any significant clinical concern, even if the mammogram is negative.

BIRADS acknowledges that screening is appropriately practiced in two major settings. In many centers there is a radiologist on-site, and additional imaging is performed immediately when a possible abnormality is detected. In an effort to reduce the cost of screening, so that it can be available for all women, screening is increasingly being performed in high-quality and highly efficient screening centers or using mobile units, where there is no radiologist on-site and the mammographic interpretation is not rendered immediately. This means that the patient may be recalled for additional study to evaluate possible abnormalities detected at screening. Regardless of the approach, until tomosynthesis has been validated, screening should include two-view mammography, incorporating the mediolateral oblique and craniocaudal (CC) projections, because single-view mammography has been shown to overlook as much as 25% of breast cancers (14).

These two approaches to screening are acknowledged in the reporting system. In the BIRADS report approach, it is required that all mammograms have a final assessment that is decision oriented. The lack of a decision in the final assessment is not acceptable. Consequently, women who require additional imaging after a screening mammogram are considered as having an incomplete evaluation. The evaluation is incomplete until a final assessment can be reached.

The 4th edition of BIRADS can be misinterpreted as supporting screening with US. In fact, the ACR does not support screening with US. In the introduction to BIRADS, the work by Kolb et al is cited where they claim to find cancers, using US, that are not visible by mammography. Unfortunately, in these studies, since the US examiner was not blinded to the mammography results, the true sensitivity of US remains undetermined. Furthermore, the detection of cancers alone using US has not been shown to reduce mortality. The suggestion that this was an adjunctive use of US (mammography was the screening test) ignores the facts. It is screening when a test is used to find occult breast cancer, no matter how many studies have been done first. US should not be used for screening unless it is within the context of a legitimate scientific trial.

The Breast Imaging Lexicon

Lexicon is just a different name for a dictionary. The lexicon that is included in BIRADS is to be used in breast imaging interpretation. The cases at the end of this chapter provide some images to help to clarify definitions, but the reader is directed to the ACR BIRADS Breast Imaging Atlas for examples provided by the ACR. The terms chosen in BIRADS are defined in the lexicon and are intended to be used to provide clear, unambiguous, and accurate communication of the mammographic findings. BIRADS has been expanded from its original application for x-ray mammography and now includes US and MRI, although the latter two are still being modified. Definitions in the lexicon were arrived at by the BIRADS committee after lengthy discussions and input from radiologists and clinicians across the country. In the interest of clarity, some familiar terms like stellate were dropped. The terms that were ultimately included were chosen and carefully defined to provide clear and accurate communication of the findings detected by mammography. The effort has been to reduce ambiguity in imaging interpretation whenever possible.

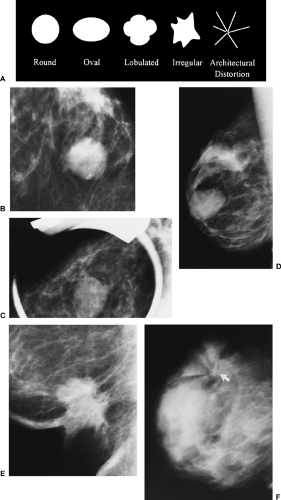

The interpreter of the mammogram should use these terms to provide a description of any significant findings in the body of the report. For masses this includes the size (maximum diameter) and shape (round, oval, lobular, irregular). The 4th edition of BIRADS drops the description of architectural distortion from the category of shape and makes it a distinct and separate entity. It is unclear why this was done. It does provide for subcategories of architectural distortion that are not always spiculated. Regardless, when only architectural distortion is seen, this should be reported and carefully evaluated. The only architectural distortion that does not require further evaluation is that caused by prior surgery or trauma.

The BIRADS descriptors also include margin characteristics (circumscribed or sharply defined, microlobulated, obscured, indistinct or ill-defined, and spiculated). A common problem has been clarified. A margin is sharply demarcated when at least 75% of it is well defined, with the remainder no worse than obscured by overlapping normal-appearing tissue.

BIRADS provides terminology for the relative x-ray attenuation of a lesion by defining its density. These are high, equal density or isodense, low density (not fat containing), or fat containing/radiolucent.

One of the changes in the 2003 Atlas is the suggestion

that “if a potential mass is seen in only a single projection it should be called an ‘asymmetry’ until its three-dimensionality is confirmed [or excluded].” This is probably a reasonable change, but I am concerned that it might be misinterpreted by lawyers, who carefully scrutinize our literature and try to twist our semantics to mean something unintended. Since all radiologists know that the term a density (this is a noun only among radiologists!) means an area of nonspecific increased x-ray attenuation, I prefer to use the term a density for something that is evident on the mammogram that cannot be more accurately categorized but does not require a biopsy. Unless a mass can be accurately determined to be benign, most masses should probably should be biopsied since the term mass is too easily misconstrued, or the term should not be used, given it has a pejorative sound in lay language.

that “if a potential mass is seen in only a single projection it should be called an ‘asymmetry’ until its three-dimensionality is confirmed [or excluded].” This is probably a reasonable change, but I am concerned that it might be misinterpreted by lawyers, who carefully scrutinize our literature and try to twist our semantics to mean something unintended. Since all radiologists know that the term a density (this is a noun only among radiologists!) means an area of nonspecific increased x-ray attenuation, I prefer to use the term a density for something that is evident on the mammogram that cannot be more accurately categorized but does not require a biopsy. Unless a mass can be accurately determined to be benign, most masses should probably should be biopsied since the term mass is too easily misconstrued, or the term should not be used, given it has a pejorative sound in lay language.

There is now a separate BIRADS category for architectural distortion. BIRADS defines this as:

thin lines or spiculations radiating from a point and focal retraction or distortion of the edge of the parenchyma. Architectural distortion can also be associated with a mass, asymmetry, or calcifications. In the absence of appropriate history of trauma or surgery, architectural distortion is suspicious for malignancy or radial scar and biopsy is appropriate.

These are the characteristics that most experts acknowledge as useful for the general characterization of noncalcified lesions.

BIRADS Special Cases

Some findings are fairly typical in appearance and, as such, they have been defined separately. The lexicon includes definitions for these special situations, such as a tubular density, which may also be called a dilated duct. The typical intramammary lymph node is also defined as such. These require no further description.

Asymmetries

I have found that many radiologists have some difficulty with defining the various asymmetries that occur when one breast is compared to the other. BIRADS has tried to organize the definitions. In 1989 we defined asymmetric breast tissue in our article that concluded that most were normal variations (15). BIRADS has tried to further clarify the topic by calling asymmetric breast tissue global asymmetry while using our definition that there is “a greater volume of breast tissue [in one breast relative to the other] over a significant portion of the breast,” and reaffirming our definition by stating that with global asymmetry, “There is no mass, distorted architecture, or associated suspicious calcifications.” I would add that it should also not be a new change that has developed since a previous study (assuming that old images are available). BIRADS also includes the conclusion of our study that global asymmetry (asymmetric breast tissue) is a normal variation and is only of concern if it “corresponds to a palpable abnormality.”

BIRADS tries to explain a focal asymmetry with varying success. I think the BIRADS approach may add to the confusion since asymmetric breast tissue, as we studied it, did not require that it involve “at least a quadrant,” as BIRADS defines global asymmetry, and our study showed that asymmetric breast tissue can be a fairly small, focal volume. I prefer to use the term focal asymmetry when I first note an asymmetry. Then, based on closer inspection, I try to determine if it represents a mass or just asymmetric breast tissue. If I do not believe it is a mass, but I believe it is a benign finding and wish to follow it at short interval, I call it a vague density to indicate that it is likely an island of normal tissue and I want to follow it at short interval to increase my confidence in the diagnosis. BIRADS, however, defines a focal asymmetry as:

a finding that does not fit the criteria of a mass. It is visible as a confined asymmetry with a similar shape in two views, but completely lacking borders or the conspicuity of a true mass. It could represent an island of normal breast tissue, particularly when there is interspersed fat…

My preference is to divide asymmetric tissues in the following manner:

A focal asymmetry is noted. Further inspection should characterize it as one of the following:

The asymmetry is actually a mass that is evident three-dimensionally and is centrally dense, with the density fading toward the periphery.

The asymmetry is likely an island of breast tissue, and does not have the characteristics of a mass. Nevertheless, the radiologist is not happy completely dismissing it. I would term this a vague asymmetry that is probably benign and would follow it at 6-month intervals for 2 years to be sure that it remains stable.

If there is no mass formation, no associated architectural distortion, no significant associated calcifications, and it has not developed since a previous study, then I would classify it as a normal variation, benign asymmetric breast tissue, and would not recommend any further investigation unless there was a corresponding palpable asymmetry.

Calcifications

The various types of calcium deposits are defined in the BIRADS lexicon. They are divided into those that are typically benign and distinguishable as such, such as skin deposits and vascular calcifications, as well as the coarse, popcornlike appearing calcifications of an involuting fibroadenoma and the rodlike calcifications of secretory deposits. BIRADS has added round calcifications to those that are typically benign and allows the use of the term punctate when round calcifications are very small (under 0.5 mm).

Also included among the typically benign calcifications are lucent-centered deposits, such as those caused by fat necrosis. Other benign deposits include eggshell or rim calcifications, which form from fat necrosis, in the walls of cysts, and occasionally at the periphery of fibroadenomas. The classic appearance of precipitated calcium in milk of calcium, the typical knots and curvilinear deposits formed by sutures, and the large dystrophic calcifications that are commonly found in the irradiated breast are also included in the typically benign group.

Also included among the typically benign calcifications are lucent-centered deposits, such as those caused by fat necrosis. Other benign deposits include eggshell or rim calcifications, which form from fat necrosis, in the walls of cysts, and occasionally at the periphery of fibroadenomas. The classic appearance of precipitated calcium in milk of calcium, the typical knots and curvilinear deposits formed by sutures, and the large dystrophic calcifications that are commonly found in the irradiated breast are also included in the typically benign group.

The next BIRADS group of calcifications are those that are of “Intermediate Concern—Suspicious.” These have a high enough likelihood of malignancy that a biopsy is indicated to determine their etiology. Amorphous or indistinct calcifications are included in this group. I believe that, when analyzing amorphous calcifications in particular, the distribution of the deposits is even more important. When amorphous calcifications are scattered over large volumes of breast tissue they are invariably benign. When they are in an irregular cluster, they become of greater significance.

I believe that BIRADS has made a mistake by suggesting that coarse calcifications be included in the group of those with intermediate concern. Any kind of benign calcification can be found coincidentally with a cancer. In my experience cancer never produces only coarse calcifications. When these have been associated with cancer, there have always been other, more suspicious calcifications. To avoid confusion I would urge that the term coarse calcifications be reserved for benign deposits. Coarse calcifications are those whose particle size is usually more than 1 mm in diameter (certainly greater than 0.5 mm). I would have no objection to placing any borderline cluster of coarse calcifications into short-interval follow-up, but I do not believe that the data support the biopsy of coarse calcifications unless they are associated with more suspicious deposits.

The third BIRADS classification of calcifications includes those with a higher probability of malignancy. These are the pleomorphic or heterogeneous calcifications, or those that are fine linear and/or branching calcifications.

Some BIRADS Changes That Should Not Have Been Made

As noted above, there have been several changes in the 4th edition of BIRADS that I believe should not have been made. Under section B, the atlas now states: “When vascular calcifications are noted, especially in women under 50 years of age there are data to suggest potential risk of coronary artery disease.” This should not have been included in BIRADS since the data are actually quite weak and heavily compromised by selection biases in the studies cited. In fact, the arterial calcifications that appear in the breast are a totally different etiology than those found in the coronary arteries. In the breast the calcifications are due to Mönckeberg’s cystic medical necrosis. This process is unrelated to the atherosclerotic, intimal calcifications found in the coronary arteries. Until there are strong data supporting a true risk relationship, the presence of vascular calcifications in the breast should not be described as suggesting any increased coronary risk.

BIRADS, 4th edition, is also less stringent in defining punctate calcifications. As the term suggests, I believe the term punctate should be reserved for pinpoint (very tiny) calcifications. On film/screen images, punctate calcifications have the appearance of someone literally puncturing the film with a sharp pin. I would urge the term be reserved for pinpoint calcifications.

Amorphous calcifications are considered by BIRADS, 4th edition, to be of “Intermediate Concern.” This is fine, but, in my experience, amorphous calcifications are almost always due to benign processes. The term amorphous suggests to me that the particles are fuzzy, roundish, and indistinct. This should be distinguished from pleomorphic, irregularly shaped calcifications that are indistinct (more worrisome). I have no data to prove it, but I believe that amorphous calcifications are usually due to powdery particles that are suspended in the fluid of very small cysts. As a suspension, rather than a precipitate, they are indistinct on the mammogram. Another possible explanation is that amorphous calcifications might be due to adenosis. The lobular acini increase dramatically in number so that the lobule, three-dimensionally, looks like a porcupine. If calcifications form in the quill-like acini, then the mammographic appearance of these collected calcifications (which are too small to be individually resolved by mammography) will be amorphous. In my experience the calcifications associated with breast cancer are only very rarely amorphous.

BIRADS, 4th edition, has also permitted the use of the term “coarse” when describing calcifications of intermediate concern. I believe this is a mistake. In my experience coarse calcifications are large (greater then 0.5 mm and usually 1 mm or larger) and virtually always due to a benign process. Cancer can rarely develop coarse calcifications, but these lesions invariably contain many small pleomorphic calcifications that indicate the lesion is a problem. Cancers can also coincidentally develop alongside, or even around, a benign process, so that the benign calcifications appear to be due to the cancer when they were actually “innocent bystanders.” I do not believe the term coarse should be used to describe suspicious calcifications. I believe that the guidance chapter in BIRADS, 4th edition, is incorrect when it suggests that “as an isolated cluster ‘coarse heterogenous’ calcifications, however, have a small but significant likelihood of malignancy…” I do not believe that this is substantiated, and the remainder of the sentence explains the situation as I have noted above: “… especially when occurring together with small, pleomorphic calcifications.” It is the small pleomorphic calcifications that raise the suspicion, not the coarse calcifications.

I will suggest that these be corrected in the next edition of BIRADS.

Distribution Modifiers

Although the morphological characteristics of individual calcifications is important for determining their significance, the distribution of the particles in the breast is also an important criterion. The description of calcifications should be qualified by the use of the distribution modifiers, as follows:

Grouped or clustered. Although most calcifications are benign when they form in a group or nonspecific cluster, if they are pleomorphic and there are 5 or more, then suspicion is warranted.

Linear. A linear distribution is just as it suggests: the calcifications are arrayed in a distribution that approximates a line. Since this suggests a ductal distribution, and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) forms in ducts, deposits that form a line are suspicious.

Segmental. These are calcifications that appear to be forming in a lobe or segment or portion of a lobe or segment. The inference is that they are in a ductal distribution, and, since DCIS can spread in the ducts as they branch to form a lobe or segment, this is a suspicious distribution of calcifications.

Regional. These are calcifications that are distributed over a large volume of the breast, but do not appear to be segmental in their distribution (the first example in BIRADS, 4th edition, actually is not a good one in that it shows calcifications that are clearly in ducts and segmental, as are the malignant calcifications in the example on page 115). Regionally distributed calcifications are invariably benign (see diffuse/scattered below).

Diffuse/scattered. These are calcifications that are distributed throughout most of the breast. They are virtually always due to a benign process or processes. In the few cases that we have seen where cancer calcifications have been distributed regionally or diffusely, the calcifications have been so pleomorphic that the diagnosis has been obvious.

The total evaluation of calcifications includes their number, size, morphology, and distribution. All of these are defined in BIRADS.

Lesion Location

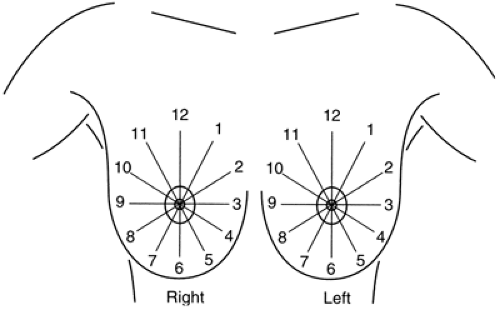

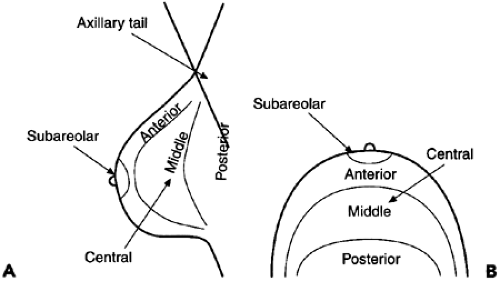

As with masses, the location of significant calcifications should be included in the report. To facilitate the clinician’s understanding of the location of an imaging-detected lesion, BIRADS has adopted the clinical reference system that uses the face of a clock to define location (Fig. 25-2) and divides the breast into anterior, middle, and posterior (deep) tissues (Fig. 25-3). This does require that the radiologist convert the location, as determined on the mammogram, into the clinical reference system.

Associated Findings

With the detection of smaller and smaller cancers, associated findings such as skin retraction and thickening have become much less common. Additional definitions are provided in the lexicon for associated findings, including skin or nipple retraction, skin or trabecular thickening, adenopathy, and others, so that the descriptive portion of the report is complete. A thorough discussion of the descriptors can be found in an article by D’Orsi and Kopans (16).

BIRADS, 4th edition, includes BIRADS for US and BIRADS for MRI. The terminology for these is discussed in Chapters 17 and 20.

BIRADS as a Reporting System

In addition to the lexicon that defines the terminology, the heart of BIRADS is the reporting system (17). This defines

the report organization and requires the interpreter to decide on the significance of the mammographic findings. A vague report is not permitted. There are now 6 specific categories of assessment that include category 0 (used in the autonomous screening setting, which means that additional evaluation is required), and the interpreting physician must be decisive in determining which category is appropriate. The report should include:

the report organization and requires the interpreter to decide on the significance of the mammographic findings. A vague report is not permitted. There are now 6 specific categories of assessment that include category 0 (used in the autonomous screening setting, which means that additional evaluation is required), and the interpreting physician must be decisive in determining which category is appropriate. The report should include:

Figure 25-3 The breast is divided by depth into anterior, middle, and posterior tissues, as seen in the lateral (A) and craniocaudal (B) projections. |

A brief description of the reason for the examination.

Mention of comparison with any pertinent previous studies.

A brief description of the type of breast tissues being analyzed, to provide the referring physician an estimate of the expected sensitivity of the mammogram (the sensitivity of mammography is diminished if the tissues are dense).

A description of any pertinent findings.

For masses:

Size (generally the largest diameter—spicules are not included if there is a visible mass).

Shape.

Margin characteristics.

X-ray attenuation.

Associated calcifications.

Associated findings and location in clinical terms (using the face of a clock).

For calcifications:

Morphology.

Distribution.

Associated findings.

Location (based on the clinical location).

One of six decision-oriented assessments outlining a course of action.

The Breast Imaging Report

In addition to noting any comparison to previous studies, BIRADS requires that the report should include a statement of the general breast tissue type, with four categories that are similar to those originally described by Wolfe:

“The breast is almost entirely fat. (Less than 25% fibroglandular).”

“There are scattered fibroglandular (approximately 25% to 50% fibroglandular).”

“The breast tissue is heterogeneously dense which could obscure detection of small masses (approximately 51% to 75% fibroglandular).”

“The breast tissue is extremely dense. This may lower the sensitivity of mammography (greater than 75% fibroglandular).”

If an implant is present, it should be stated in the report (2).

These descriptions of tissue patterns are provided as an indication of the likely sensitivity of the test (3,4), acknowledging (18,19) that mammography is less sensitive in the dense breast and alerting the referring physician as to the type of breast being evaluated.

The body of the report should include a description of significant findings using the appropriate descriptors, any associated findings, the size of the abnormality, and its location. Any findings should be described in the report using BIRADS terminology provided by the BIRADS lexicon.

The following language is taken from BIRADS. The accompanying figures are my interpretation of those descriptions:

Masses are space-occupying lesions seen in two different projections. If a potential mass is seen in only a single projection, it should be called an asymmetry (I believe that it should still be called a density) until its three-dimensionality is confirmed.

Shape (Fig. 25-4A).

Round (Fig. 25-4B): a mass that is spherical, ball shaped, circular, or globular.

Oval (Fig. 25-4C): a mass that is elliptical or egg shaped.

Lobular (Fig. 25-4D): a mass that has contours with undulations.

Irregular (Fig. 25-4E): the lesion’s shape cannot be characterized by any of the above.

Architectural distortion is now a separate category (Fig. 25-4F). The normal architecture is distorted with no definite mass visible. This includes spiculations radiating from a point and focal retraction or distortion of the edge of the parenchyma. Architectural distortion can also be an associated finding.

Margins (these modify the shape of the mass) (Fig. 25-5A).

Circumscribed (well-defined or sharply defined) margins (Fig. 25-5B) are sharply demarcated with an abrupt transition between the lesion and the surrounding tissue. Without additional modifiers, there is nothing to suggest infiltration.

Microlobulated margins (Fig. 25-5C) undulate with short cycles producing small undulations.

Obscured margins (Fig. 25-5D) are hidden by superimposed or adjacent normal tissue and cannot be assessed any further.

Indistinct (ill-defined) margins (Fig. 25-5E) are poorly defined and raise concern that there may be infiltration by the lesion that is not likely because of superimposed normal breast tissue.

Spiculated margins (Fig. 25-5F). The lesion is characterized by thin lines radiating from the margins of a mass. If there is no visible mass, the basic description of architectural distortion

with spiculation as a modifier should be used.

Special cases.

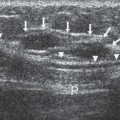

An asymmetric tubular structure or solitary dilated duct (Fig. 25-6) is a tubular or branching structure that likely represents a dilated or otherwise enlarged duct. If unassociated with other suspicious clinical or mammographic findings, it is usually of minor significance.

Intramammary lymph nodes (Fig. 25-7) are typically reniform or have a radiolucent notch due to fat at the hilum and are generally 1 cm or smaller in size. They may be larger than 1 cm and normal when fat replacement is pronounced. They may be multiple, or marked fat replacement may cause a single lymph node to look like several rounded masses. This specific diagnosis should be made only for masses in the lateral half and usually upper portion of the breast.

Global asymmetry is the term for what we described as asymmetric breast tissue (see discussion earlier) (Fig. 25-8). This is judged relative to the corresponding area in the other breast and includes a greater volume of breast tissue, greater density of breast tissue, or more prominent ducts. There is no focal mass formation, no central density, no distorted architecture, and no associated calcifications. Asymmetric breast tissue usually represents a normal variation but may be significant when it corresponds to a palpable asymmetry.

Focal asymmetric density (Fig. 25-9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree