The Male Breast

Although it is extremely uncommon, breast cancer occurs in males, and its incidence is increasing (1). In 2005 the American Cancer Society estimated that 211,240 women would develop invasive breast cancer, while only 1,690 males would be diagnosed in the United States (2). Just as with women, the prognosis for men is related to the size of the cancer and its stage (axillary lymph node status) at the time of diagnosis. Just as the incidence of female breast cancer has been increasing steadily over the years, so has the incidence of male breast cancer (3). From 1973 to 2000, the incidence of male breast cancer rose from 0.85 to 1.3 per 100,000 men; among females it increased from 98 to 135 per 100,000.

Although some of the increase among women can be attributed to mammography screening, the facts that men are rarely screened and that the incidence of breast cancer among males has increased over time support that the increase in incidence among women is not due just to early detection. Anderson et al (3) observed the peak incidence among men was age 71, while women appear to have an “early-onset” peak at around age 52 and a later peak around age 71. Giordano et al reported (1) that the median age for breast cancer in men is 67, while in women it is 62. Among men the incidence increases steadily with increasing age, while in women the “premenopausal” incidence appears to increase more rapidly than the increase in incidence that appears at more gradual slope after menopause. Men also tend to have more indolent, lower-grade, estrogen receptor (ER)-positive tumors, similar to postmenopausal women (90.6% in men vs. 76% in women). Premenopausal women are more likely to have higher-grade, ER-negative, more aggressive cancers.

Giordano et al (1) reported that men rarely had lobular cancers (1.5%), while lobular cancers made up 11.8% of female breast cancers, likely reflecting the fact that men do not form lobules. The 5-year survival rate for men was 63%, the 10-year survival rate 41%.

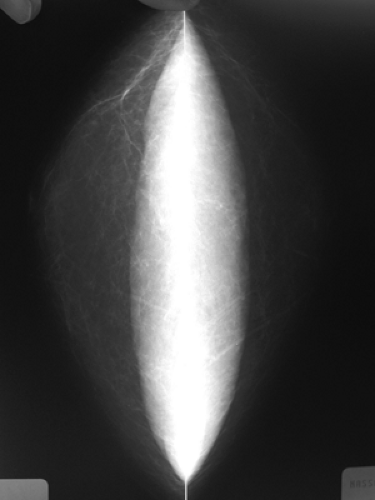

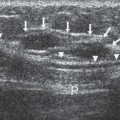

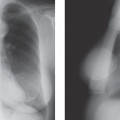

In our experience, most men are referred for breast imaging because the individual or his physician feels an asymmetric thickening or a mass in one breast that is not felt in the other. Pain and tenderness are not unusual. Rarely the breast is enlarged. These signs and symptoms are almost always caused by asymmetric gynecomastia (Fig. 19-1). Men with symmetric breast enlargement or symmetrical subareolar thickening are rarely referred for breast imaging because the diagnosis is evident by clinical examination. Even when gynecomastia is asymmetric on the clinical examination, the x-ray findings are usually apparent by mammography, although to a lesser degree, in the contralateral breast.

Figure 19-1 Asymmetric gynecomastia. Most mammograms in men are performed for asymmetric thickening or a mass. This 52-year-old man had asymmetric gynecomastia greater on the left than the right. |

Using mammography, Chantra et al, in a review of 118 cases at a referral center, observed bilateral gynecomastia in 66 male patients (55%), unilateral gynecomastia in 30 (25%), bilateral fatty enlargement (pseudogynecomastia) in 9 (8%), unilateral fatty enlargement (pseudogynecomastia) in 2 (2%), lipomas in 5 (4%), normal male breast tissue in 3 (3%), and breast cancer in 3 (3%) (4).

Anatomy, Histology, and Pathology of The Male Breast

At birth, the male and female breasts are the same. Histologically, the normal male breast contains subareolar ducts similar to those found in prepubertal girls. In most males these never develop further. However, when stimulated by hormones or a variety of drugs, the ducts in a male may elongate and branch. One of the prominent differences between gynecomastia and the female breast is that lobule formation in the male breast is extremely rare. This likely explains why lesions of the lobule (e.g., fibroadenomas) found in women are very rare in men. Cysts may develop, but they, too, are rare in men, and I suspect that cysts in men are actually cystic dilatations of the ducts and not the same as much of the cyst formation in females, which is due to apocrine metaplasia in the lobules. Because the male breast contains ductal epithelium, however, carcinoma can develop.

Gynecomastia

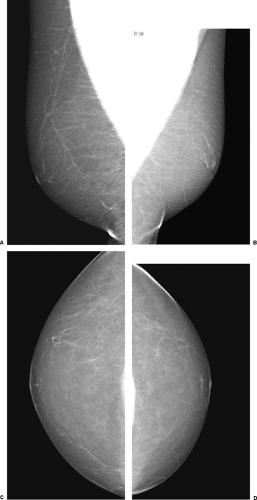

The normal male breast is very simple. The male has a small nipple, a small areola, and subcutaneous fat (Fig. 19-2). No fibroglandular tissue is visible under the nipple of the normal male.

Gynecomastia is simply defined as nonneoplastic enlargement of the male breast. This condition has a range of manifestations. The breast may enlarge predominantly due to fat deposition; this has been called “pseudo-gynecomastia” (Fig. 19-3). If the enlargement produces firm tissue under the nipple, this suggests the presence of actual breast tissue and not just fat. This may be a diffuse thickening or a disk-like formation under the nipple. With true gynecomastia the ducts increase in number and may become dilated. Proliferation of the epithelial and myoepithelial elements occurs, with the frequent development of epithelial hyperplasia. The surrounding stroma demonstrates increased vascularity and cellularity and may contain inflammatory cells. Edema is a common component of gynecomastia.

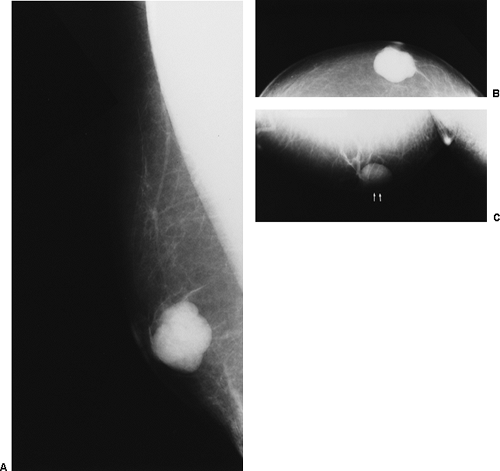

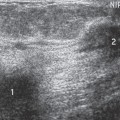

When the process becomes inactive, a hyalinized stroma may persist. Although uncommon, lobule formation can occur and secretions may be produced. This apparently is most common when exogenous estrogens are administered for prostate cancer therapy, although we have seen spontaneous cyst formation in an adolescent boy as well as in a 67-year-old man (Fig. 19-4). Although atypical hyperplasia and carcinoma in situ have been found in association with gynecomastia, there is no strong evidence that this predisposes the male to the development of breast cancer. Since the risk of developing gynecomastia increases with age, as does the risk of developing breast cancer, the likelihood of both occurring together also increases.

Clinically, breast enlargement may be unilateral or bilateral. There may be skin thickening, and soreness is a common complaint. Axillary nodal enlargement may be present, despite the benign etiology of the breast changes.

Gynecomastia has a bimodal prevalence first seen around the time of puberty, with a second peak beginning around age 50. This is likely due to the fact that these are periods of hormonal instability. Gynecomastia has been associated with endogenous hormonal imbalance, the use of exogenous hormones, hormone-producing tumors, hepatic disease (including hepatoma), renal disease, and hyperthyroidism. Numerous drugs have been associated with the development of gynecomastia.

Transient changes are fairly common in the adolescent male (Fig. 19-5), but these are usually self-limiting and regress as hormone activity stabilizes. Drugs such as reserpine, cardiac glycosides, spironolactone, cimetidine, and thiazides, as well as marijuana, are among the many that have been associated with gynecomastia.

Testicular tumors, such as embryonal cell carcinoma, seminoma, and choriocarcinoma, may result in gynecomastia (5), and the testes should be checked when breast enlargement occurs. Other conditions that affect the testes, including Klinefelter’s syndrome, have been associated with gynecomastia. Klinefelter’s syndrome also has an increased association with the development of breast cancer (6). Chronic hepatic disease may result in gynecomastia owing to the reduced ability of the liver to eliminate estrogen compounds normally produced by men. There are reports that link gynecomastia with lung diseases, including lung cancer. Finally, as might be expected, the use of exogenous estrogens produces breast development in the male.

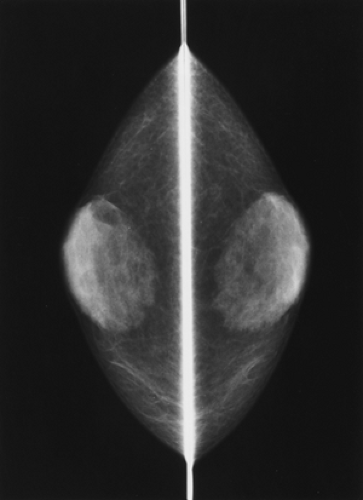

Breast Cancer in Men

As noted earlier, breast cancer in men is extremely uncommon: fewer than 1% of breast cancer cases diagnosed each year occur in men. As in women, its cause remains to be elucidated. Gynecomastia does not appear to increase the risk, although significant exposure to ionizing radiation does (Fig. 19-6), and there is an increased incidence in those with Klinefelter’s syndrome.

The mean age at which men develop breast cancer is approximately 5 to 10 years later than for women. In one series of 45 male cancers occurring over a 15-year period

in a health maintenance organization, the age ranged from 36 to 82, with a mean of 60 and a median of 61 (7). In another series, one man of the 16 subjects with breast cancer was age 27; the others were 60 or older (8).

in a health maintenance organization, the age ranged from 36 to 82, with a mean of 60 and a median of 61 (7). In another series, one man of the 16 subjects with breast cancer was age 27; the others were 60 or older (8).

A review of 1,429 cases of male breast cancer in the Nordic countries revealed that younger men tended to have better survivals than older men (9). Although some series have suggested a poorer prognosis for men with breast cancer than for women, this is probably due to case-selection bias, with more advanced disease being treated in the teaching institutions that report the data. It appears that for comparable stages, the prognosis for men is similar to that for women (10,11). In a review of 355 cases, the 5-year survival was 90% if lymph nodes were negative, 73% if one to three nodes were positive, and 55% if four or more nodes were positive, with corresponding 10-year survivals of 84%, 44%, and 14% (11).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree