The Mediastinum and the Hila

The mediastinum is a real challenge.

First, radiographic appearances vary considerably in their range of normality here, making it difficult to decide what is normal and what is not.

Second, the mediastinum is a complex structure; abnormalities in specific areas are often subtle and will be missed unless a systematic and sequential approach is adopted as discussed in Chapter 1.

Third, the differential diagnosis of abnormal mediastinal shadowing is diverse and complex.

For these reasons, I like to divide the mediastinum into four ‘geographic departments’ – superior, anterior, middle and posterior – and combine this with a knowledge of the normal anatomical structures that exist within each. This facilitates a structured approach to the differential diagnosis of abnormal shadowing within each compartment. However, before expanding on this approach, it is useful to consider the hilar shadows separately.

THE ‘BULKY’ HILUM

There are a few basic points to consider first:

In a healthy person, the hilar shadows are created by the pulmonary arteries and veins with a small contribution from the major bronchi. The latter appear as narrow line shadows outlined on the one hand by the air contained within them and on the other by adjacent, aerated lung.

The normal hilar shape is derived from the upper lobe vessels meeting the basal artery and it therefore resembles a letter ‘y’ lying on its side. The normal shape will be distorted if one limb of the ‘y’ disappears as a result of collapse of an upper or lower lobe or if additional structures are present, especially abnormal hilar lymph nodes.

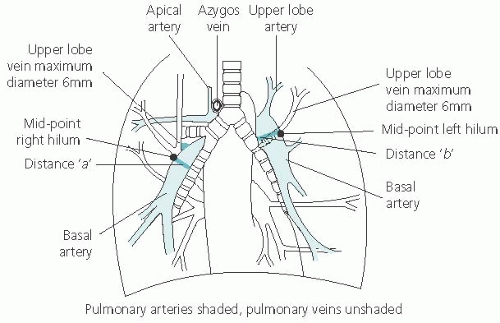

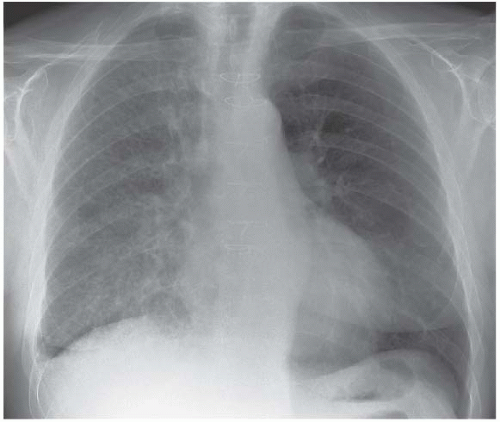

The size of each hilum is best assessed from the size of the respective basal artery, which can usually be identified on a well-penetrated radiograph (Fig. 2.1). The basal artery commonly tapers before it divides into the basal segmental arteries and a convenient and relatively reproducible means of measuring its diameter is at its mid-point. This can be arbitrarily considered to represent the mid-point of the hilum and is the point where the most lateral upper lobe pulmonary vein crosses the basal artery (arrowed). With practice, the lateral upper lobe vein can usually be identified from its typical orientation.

Starting at the mid-point of the basal artery, measure from its lateral wall to the clearly defined transradiancy of the intermediate bronchus. This is shown in Fig. 2.1 as distance ‘a’ and varies in healthy middle-aged adults between 7 and 19 mm with a mean of 14 mm (the measurement ‘a’ includes the lateral wall of the intermediate bronchus but this is only about 2 mm and is relatively constant).

The left basal artery is roughly the same size (but commonly 1-2 mm smaller in diameter) when measured at its mid-point, where the most lateral upper lobe vein crosses it (distance ‘b’ in Fig. 2.1).

Quantifying the size of the hilar shadows in this way may seem complicated at first but the exercise becomes much easier with practice and it does add far more objectivity to the assessment of hilar enlargement.

Clear landmarks are also necessary for identifying the normal position (vertical level on a radiograph) of each hilum. The mid-point of each hilum is identified as described above (arrowed in Fig. 2.1). The mid-point of the right hilum is then opposite the horizontal fissure which meets the sixth rib in the axilla and is also roughly at the level of the third rib anteriorly on deep inspiration. The centre of the left hilum is 0.5-1.5 cm higher. The centre point on each side will be 2-3 cm higher in upper lobe shrinkage and 1-2 cm lower in lower lobe shrinkage.

An abnormally prominent hilum is either caused by exaggerated vascular shadowing or by pathological enlargement of non-vascular structures and it is important to attempt to distinguish between the two possibilities. First, the area medial to the mid-point of the right basal artery is the lumen of the intermediate bronchus and it should be radiolucent. Any distortion suggests abnormal pathology, especially lymphadenopathy. Second, identify obvious vascular shadows in the central lung fields and trace them into the hilum. Continue to dissect the hilum in this way and if any component is not obviously vascular in nature, it may well be pathological.

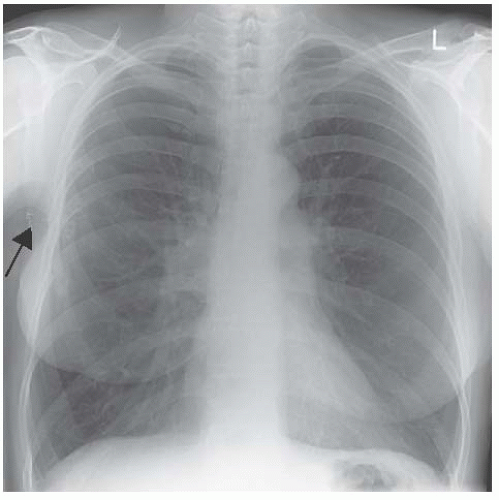

Although neither of these tips is infallible they do help in deciding if further investigation such as a mediastinal computed tomography (CT) scan is indicated. Figure 2.2 is the chest radiograph of a woman with Eisenmenger’s syndrome.

Employing the principles just discussed, we can be confident of the vascular nature of the huge hilar shadows (‘a’ measures 50 mm and ‘b’ 45 mm).

A final word regarding normal measurements. Each upper lobe pulmonary vein is 4-6 mm in diameter where it meets its respective basal artery and enlargement occurs in pulmonary venous congestion due to heart failure or mitral valve disease.

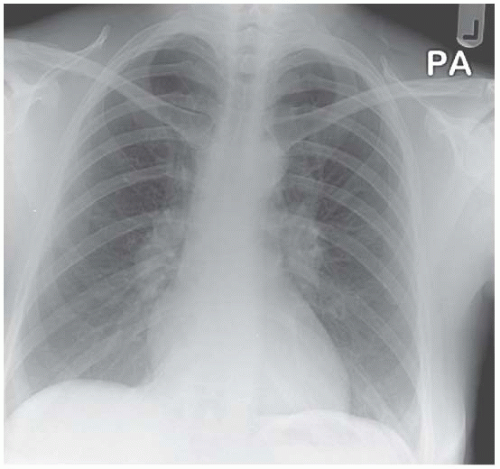

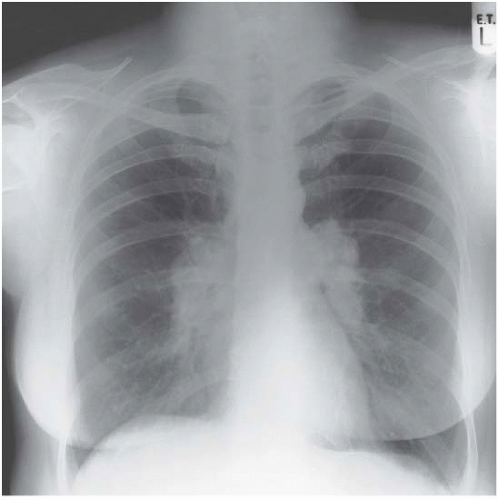

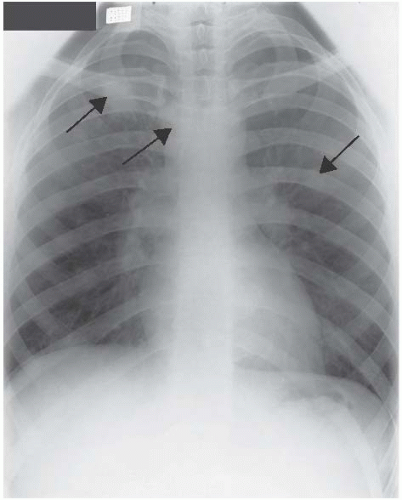

Figure 2.3 also shows prominent hila due to vascular enlargement. This woman had pulmonary hypertension as a result of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Figure 2.4 is an example of bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy in sarcoidosis. Although the medial border of the right basal artery is still outlined, the general ‘lumpiness’ of both hilar shadows isn’t comfortably explained by vascular enlargement. Figure 2.5 emphasizes this point as a more florid example of sarcoid-related bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.

Note the abnormal shape of the right breast and the metal clips in the right axilla in Fig. 2.3. This woman had undergone surgical treatment for carcinoma of the breast with lumpectomy and axillary lymph node clearance. There are also healing fractures of ribs 3, 4, 5 and 6 on the right, which were fortunately traumatic, not metastatic. Only a systematic approach will ensure that all of these abnormalities are detected.

If you think the hila may be abnormal, search for additional clues on the radiograph. In Fig. 2.6 paratracheal lymphadenopathy and multiple patches of consolidation can be seen in the lung fields as well as right hilar enlargement – the diagnosis was long-standing sarcoidosis. A mass in the lung fields in addition to an abnormal hilum is highly suggestive of malignancy. Exclude small pleural effusions and look for evidence of a pulmonary infiltrate in association with hilar enlargement (Fig. 2.7).

These are examples of enlarged hilar shadows but sometimes one or other hilum may appear to be smaller than normal. This is seen (together with hyperlucency of the right lung) in Macleod’s syndrome and occasionally in other situations (Fig. 2.8).

Figure 2.6 Chronic sarcoidosis – paratracheal lymph node enlargement and areas of pulmonary infiltration (both arrowed) in association with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. |

Figure 2.8 An apparently small right hilum, which is pushed downward (the ‘y-on-side’ is distorted) by a large emphysematous bulla. |

Macleod’s syndrome: Swyer and James in 1953 and then Macleod, in 1954, described unilateral hyperlucency of one or other lung field and the condition was ascribed to severe neonatal or childhood bronchiolitis, resulting in destruction of lung units during the active period of their development. The chest X-ray is diagnostic with a normal-sized or small lung in association with a small hilum and pulmonary vessels that are distributed sparsely throughout the respective lung field.

CAUSES OF HILAR ENLARGEMENT