The Medical-Legal Problem and Breast Imaging

In our litigious society, the failure to diagnose breast cancer has become the leading cause of malpractice claims, and this is likely to increase. It is virtually impossible to be protected from a lawsuit, and, even if the physician performs at a very high level, a jury may still decide, based on pity for a woman dying of breast cancer, to find for the plaintiff against the physician. The contingency fee system, in which a lawyer stands to receive 30% or more of any monetary award, makes it attractive for lawyers to sue if there is any indication of possible success. The amount awarded by juries has been increasing. Jury trials are a contest that involves experts who are hired by the defendant and experts who are hired by the plaintiff. The plaintiff’s experts are there to try to convince the jury that the defendant was negligent by not living up to the standard of care in a given situation, and the defense experts are there to try to convince the jury that the defendant did live up to the standard and provided appropriate care. The plaintiff’s lawyers are there to buttress the testimony of the plaintiff’s experts and to try to discredit the defendant’s experts and their testimony, while the defendant’s lawyers are there to try to discredit the plaintiff’s experts and their testimony and to buttress the testimony of the defendant’s experts. Ultimately the jury decides whom they believe.

The failure to diagnose breast cancer has become the leading cause of medial malpractice claims. Radiologists are being sued at an increasing rate. The situation has deteriorated rapidly such that most residents are avoiding the subspecialty of breast imaging. In a survey of senior residents, Bassett et al (1) showed that, after “not an interesting field,” the greatest reason that residents were not going into breast imaging was the stress involved in interpreting the studies and the fear of being sued. Since the year 2000 there has been a marked decrease in applicants for breast imaging fellowships across the United States. Radiologists are trying to avoid reading mammograms in increasing numbers. This has all occurred at a time when the randomized controlled trials have shown that mammography screening can reduce the death rate by 25% to 30% (2). This benefit has been confirmed in service screening in Sweden (3) and the Netherlands (4), and the death rate from breast cancer in the United States has decreased by 20% with the onset of wide-scale mammographic screening (5). All of these gains will be lost if there are not enough radiologists to read the mammograms (6).

Despite the apparently discouraging situation there is some good news. Most malpractice cases that go to trial are decided in favor of the radiologist. In addition, there are things that radiologists can do to reduce the risk of a suit and to increase the likelihood of succeeding at a trial. Perhaps the most important, and obvious, approach is to be kind and considerate to the patient. A common reason why individuals sue is because they are angry at the way they feel they have been treated. Kindness and consideration should go without saying, but in a busy practice we are often stressed ourselves, and in our haste we may seem brusque and uncaring. This should be avoided. It is important that all members of the breast imaging team, from those scheduling the studies to the receptionists down through to the radiologists, be supportive, attentive, and friendly. We look for breast cancers everyday, going through the same steps over and over so that it becomes a routine. For the woman coming to us once a year, however, it is an unfamiliar and anxiety-provoking experience. She is anxious because she is actively “looking for cancer.” She will be exposing an intimate part of her body to a stranger who will unceremoniously pull and tug on it and place it in what is perceived as a vise, which squeezes what the

patient perceives as a delicate organ. She will not see the images, which will go somewhere else, and an impersonal report will be issued. As every mammography technologist will report, many patients manifest their anxiety in the form of hostile behavior and heightened sensitivity. The tense patient is primed for wanting to blame someone should there be an untoward outcome. Certainly, the patient, who is told that her mammogram is negative and subsequently finds she has breast cancer, is likely to be angry and to believe that something must have been done incorrectly, since all of the “propaganda” about mammograms suggests that they find all cancers early enough to result in a cure. Despite the fact that radiologists and others have been warning for years that this is not the case (7,8), the perception is that mammograms are perfect, so that, when a cancer is not detected, it is not surprising that the patient might assume that an error was made. If she is angry from the experience, she may well seek redress. The breast imaging staff should be sensitive to these facts and avoid arguments or conflicts of any kind with the patient. Efforts should be made to be sure that the patient is cared for in a friendly and supportive fashion.

patient perceives as a delicate organ. She will not see the images, which will go somewhere else, and an impersonal report will be issued. As every mammography technologist will report, many patients manifest their anxiety in the form of hostile behavior and heightened sensitivity. The tense patient is primed for wanting to blame someone should there be an untoward outcome. Certainly, the patient, who is told that her mammogram is negative and subsequently finds she has breast cancer, is likely to be angry and to believe that something must have been done incorrectly, since all of the “propaganda” about mammograms suggests that they find all cancers early enough to result in a cure. Despite the fact that radiologists and others have been warning for years that this is not the case (7,8), the perception is that mammograms are perfect, so that, when a cancer is not detected, it is not surprising that the patient might assume that an error was made. If she is angry from the experience, she may well seek redress. The breast imaging staff should be sensitive to these facts and avoid arguments or conflicts of any kind with the patient. Efforts should be made to be sure that the patient is cared for in a friendly and supportive fashion.

Tort of Negligence

Medical malpractice or negligence is covered by tort law. There are four elements that define the tort of negligence (9):

Duty. The physician must have established a duty toward the patient. This is generally implied when a service (interpreting a mammogram, etc.) has been rendered and there is an understood level of expectation for care on the part of the patient.

Breach of duty. This is the act of failing to appropriately fulfill the responsibilities implicit in the duty to the patient.

Causation. Causation means that the action or failure of the action by the physician was directly related to the injury to the patient.

Damage. This fourth element requires that the causation actually resulted in damage or loss to the patient.

What Is the Standard of Care?

A finding of negligence is based on the decision that a physician has not fulfilled his/her duty to a patient by performing as a reasonable physician in the same situation would have performed at the time the breach of duty is alleged to have occurred. In simple terms a jury finds a physician guilty of negligence if the physician failed to live up to the standard of care. The problem lies in the fact that there is no book that delineates the standard of care. There is no medical body that determines the standard of care. The standard of care that a physician practicing today will be held to will be decided by juries of the future, and the decision of one jury when a set of circumstances is reviewed carries no precedent for another jury faced with the same set of circumstances. For example, a jury may be asked to decide whether a radiologist should have used ultrasound to examine a patient who felt a lump in 1992. The question facing the jury is whether the use of ultrasound to examine a palpable abnormality was the standard of care in 1992. The jury will hear testimony from the defendant’s experts, who will argue that the use of ultrasound was not the standard of care in 1992, while the plaintiff’s experts will argue that it was the standard of care in 1992. If the jury in this case decides that the use of ultrasound, in this situation, was not the standard of care in 1992 and find for the defendant, acquitting the radiologist of negligence, this decision only applies to this one case. Despite the fact that a second case goes to trial that involving the same question, whether ultrasound was the standard of care in 1992, the results of the first case will have no bearing on the second. The jury in the second case might decide that they thought that the standard of care was to use ultrasound in 1992. Thus, in the second case, the jury could find the radiologist guilty of negligence. Given this situation, the idea that there is a legal standard of care that a physician can live up to today is simply nonsense when future juries can arrive at opposite decisions, considering the same questions. Legal experts will protest that this is because each case presents a unique set of circumstances and each case must be decided based on its merits. Clearly this often the case, but, if the question is “was the use of ultrasound to evaluate a palpable mass in 1992 the standard of care or not,” there cannot be more than one answer, except the legal system permits more than one answer. So what is the standard of care when two completely opposite answers are correct? The problem lies in the fact that there is no way of knowing what the standard of care actually is today. It will be decided when someone is sued in the future, and it will depend on each jury’s decision because one jury’s decision is not binding in any other case.

The decision of one jury as to what a physician should have done in a specific case has no bearing on the next case, even if the facts of the cases are identical. Trials do not set precedents for health care. The only precedents that may evolve in the American legal system have to do with the law itself. If a verdict is appealed, the appeal is generally based on a legal issue and not a medical question, and it is the appellate courts that determine legal precedents.

Expert Witnesses

As noted above, a malpractice trial usually involves the testimony of experts. These are individuals who are called to testify in support of a defendant or to promote the plaintiff’s

case. Although lawyers would argue to the contrary, in my experience just about anyone who has ever seen a mammogram can be considered an expert. I was once involved as an expert in a trial in which the plaintiff’s mammography expert had never heard of Dr. Daniel Kopans! In one trial, outside of Boston, where the jury found against the radiologist and awarded over seven million dollars, the plaintiff’s “expert” was a retired radiation oncologist who testified that the radiologist should have seen a cancer on a mammogram. He pointed to an area that was actually distant from where the cancer was later found (since it actually was not visible on the mammogram in question). When challenged that the cancer was found in a different location, he replied that “the cancer had grown.” The fact that this “expert,” who could not interpret mammograms was allowed, and the fact that he was able to lie with impunity points out another problem. Since experts are providing their opinions, they are not held to the standard of perjury to which the average witness must adhere, and, apparently, the expert system is so important that the legal system permits experts great leeway. Berlin (10) points out:

case. Although lawyers would argue to the contrary, in my experience just about anyone who has ever seen a mammogram can be considered an expert. I was once involved as an expert in a trial in which the plaintiff’s mammography expert had never heard of Dr. Daniel Kopans! In one trial, outside of Boston, where the jury found against the radiologist and awarded over seven million dollars, the plaintiff’s “expert” was a retired radiation oncologist who testified that the radiologist should have seen a cancer on a mammogram. He pointed to an area that was actually distant from where the cancer was later found (since it actually was not visible on the mammogram in question). When challenged that the cancer was found in a different location, he replied that “the cancer had grown.” The fact that this “expert,” who could not interpret mammograms was allowed, and the fact that he was able to lie with impunity points out another problem. Since experts are providing their opinions, they are not held to the standard of perjury to which the average witness must adhere, and, apparently, the expert system is so important that the legal system permits experts great leeway. Berlin (10) points out:

The thought of penalizing an expert witness for providing false testimony in a legal proceeding is generally viewed by the courts as abhorrent. Courts have consistently held that the expert witness should be immune to judicially administered penalties, repeatedly ruling that if experts are subjected to such action, qualified physicians and scientists will refuse to participate and assist in the administration of justice.

Compounding the problem is the fact that providing expert testimony can be very lucrative. An expert can charge whatever he or she wishes to charge for testifying, so that there is considerable financial pressure to provide expert testimony. There are Web sites that provide lists of physicians who are willing to be experts.

Failure to Diagnose

The radiologist is under unreasonable pressure to detect all cancers. The majority of lawsuits involving breast imaging are due to a failure to see a cancer on a mammogram that may or may not be visible in retrospect. The plaintiff can always find an “expert” who is willing to testify that the radiologist should have seen the lesion. This is remarkable in that there is no radiologist in the world who has not at some time failed to see a significant abnormality that is visible in retrospect, yet these experts are willing to determine that another radiologist was negligent for having made a similar oversight. The “truth” may not enter into the equation. I testified at a trial in which the plaintiff’s “expert” testified that the defendant had missed the cancer in the upper outer left breast. The only thing that was present on the mammogram in question was the normal scalloped edge of the parenchyma. Of course, the debate could have been my word against the plaintiff’s expert but for the fact that the cancer was in the medial aspect of the breast in a totally different quadrant. Despite the facts, this case still went to trial. Fortunately, the defense prevailed, seemingly vindicating the process (I am told that approximately 70% of cases that go to trial are won by the defense). What cannot be quantified, however, is the mental anguish and financial cost that is shouldered by the defendant and the defense in these cases.

The Hidden Costs of the Medical Malpractice Situation

Tort reform is an effort to reduce the financial costs of the medical malpractice situation by capping awards. What is missing from the discussions is the often grave psychological toll that occurs to a physician when he or she is accused of negligence. Physicians are trained from the first day of medical school to place the patient and the care of the patient above all else. Many, if not most, physicians often sacrifice their own personal relationships to care for their patients. There are certainly exceptions to the rule, but, in my experience, most physicians put the well-being of the patient above all else. To be accused of being negligent strikes at the core of being a physician. When a suit is filed and the physician is notified that he/she is being accused of a failure to diagnose a breast cancer, the first response is to pull the case and review it to see if a lesion was overlooked. Most of the time the case has already been removed from the file by the plaintiff’s lawyer. When the radiologist finally gains access to the case, the first impulse is to have others look at the images to see if the “missed” cancer should have been seen. This is the way radiologists practice. We are constantly showing cases to one another to get other opinions to refine the diagnosis to provide the best interpretation of the study for the patient. Unfortunately, in a malpractice case, the defendant is counseled to not do this. Anyone who is shown the images can be subpoenaed and required to testify. Thus, the radiologist is blocked from discussions with colleagues. The case usually takes a year or more before it is settled or goes to court, and the defendant must live with the uncertainty over that time, without having the ability to even show the case to others to gain some reassurance about not having “done something evil.” I know of a radiologist who was thin to begin with, lost 20 pounds, and needed psychiatric counseling while waiting several years for a trial that the radiologist won. Of course, it is important that 70% of the trials are found in favor of the radiologist, but, looked at another way, this means that 70% of radiologists sustained the trauma of being falsely accused. When I have discussed this with plaintiff’s attorneys and pointed out that the term negligence to a physician is one of the most serious accusations that could be made and is devastating, they respond that it is merely a legal term that suggests that an untoward, avoidable event took place, and the system just needs to determine how the plaintiff will be compensated.

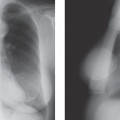

The system obviously allows for out-of-court settlements. This is one way to avoid the shame and embarrassment that many defendants experience when having to endure a trial by a jury. This is also a way for insurance companies to reduce the chance that they will lose a large amount in a jury trial. There are clearly cases where negligence has occurred. On occasion, it is also apparent that an avoidable problem did occur (although not necessarily negligence), and the patient should be compensated. Unfortunately, in the latter situation a compensation fund or insurance fund would be preferable to a suit, but this does not yet exist. Many of the cases that I have heard of where cases were settled out of court were cases where there was no negligence that occurred, but the insurance company or the radiologist did not wish to risk the possibility that a jury would find for the plaintiff, despite the absence of wrongdoing, because of the complexity of the issues involved. I remember one case in which the radiologist had gone beyond the standard of care and had even performed a clinical examination of the patient, who claimed she felt something in one of her breasts in the early 1990s. Both sides agreed that the mammogram was negative, and her own physician, as well as the radiologist, had been unable to feel anything on clinical examination. She returned several years later with a lump that all could feel in the same breast and had a new mass on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram (not visible on the craniocaudal (CC) mammogram), and ultrasound at that time revealed two masses. One turned out to be a fibroadenoma, while the other was an invasive breast cancer. She sued, accusing the radiologist of negligence for having not done an ultrasound at the first visit when there was nothing on the mammogram and nothing on clinical breast examination by two physicians. Not only was ultrasound in this situation, at that time, not the standard of care, but there are no data, even today, that prove that performing ultrasound on women who may have (or even have) palpable abnormalities has any impact on their survival. Nevertheless, facing a claim of over $1 million, the defendant’s insurance company decided to settle the case for $250,000. The radiologist, who had not been negligent, was happy to have the case behind him, but his name is now on a national list that identifies him as having had a settlement against him, and he must explain this every time he seeks new employment or relicensing. This is an outrage for an individual who had performed above the standard of care. Cases such as this amount to legalized extortion.

What About Science

The case outlined above also highlighted to me the fact that science is just beginning to enter into the legal decisions about these cases. During a sworn deposition I was asked by the plaintiff’s attorney whether the density that had appeared only on the second MLO mammogram (it was not visible on the CC) was the cancer that was later found at biopsy. Since there was also a fibroadenoma found at the same level but in another part of the breast, I replied, “No one in the world can tell you which of the lesions that is.” (It was not spiculated and was seen in only one projection.) There was a slight pause, and then it was as if I had dropped a bomb on the proceedings. The plaintiff’s attorney shouted “objection” and ordered the videotaping to stop. The lawyers began shouting at one another. Once things calmed down, I asked what had been the problem. I was told that I could not say that “No one in the world” could make that determination. I could say that I could not or that in my opinion, but I could not make such a blanket statement. Despite the fact that I pointed out that it is scientifically impossible for any individual to determine the three-dimensional location of a lesion from a two-dimensional image, I was told that I could only say that it was my opinion.

I do not mean to imply that science cannot be introduced into legal proceedings, but the courts are just beginning to accept real science. In a case known as Daubert, the courts have ruled that a judge can challenge an expert who is claiming science but is actually spouting nonsense and the judge can disqualify the expert (11). I have yet to see this happen in a breast cancer case, and experts have been allowed to tell the jury that a cancer moved from one part of the breast to another when “it grew” and that someone may be able to tell the three-dimensional location of a lesion from a single two-dimensional image.

Is There Medical Negligence?

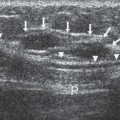

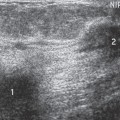

Unfortunately, there are clear cases of negligence, but, in my experience in being asked to review malpractice cases, these are the exceptions. The legal system correctly seeks to redress the wrong if a patient has been harmed because of negligence, but, in the cases that I have reviewed, this has rarely been the situation. In one of the cases that I was asked to review for a plaintiff, there had been a palpable mass. It was dense, irregular, and spiculated on the mammogram. The radiologist read the ultrasound, which was performed using an abdominal probe that did not focus to the near field, and the lesion appeared somewhat irregular and was hypoechoic (containing low-level internal echoes). The radiologist interpreted it as a benign cyst. This led to a delay in diagnosis. It would be very difficult to argue that this radiologist had not been negligent.

The standard of care can work against the patient. I was asked to review another case where a lesion deep in the breast was being localized for surgical excision using the free-hand method. The radiologist guesstimated the location of the lesion and put the needle into the breast from the front of the breast, so that the surgeon could do a circumareolar incision. The needle was positioned and mammograms were obtained in the lateral and CC projections. The needle tip was several centimeters from the lesion and was, apparently, repositioned to get it closer to the lesion,

and a wire was deployed. The next set of images show a wire traversing the breast to the chest-wall side of the film. The hook is beyond the edge of the film and is not visible on the images. It turns out that the wire ended up in the pericardium necessitating significant thoracic surgery, with the patient ending up in intensive care. On the surface this appears to be negligence. The only way the wire could have entered the pericardium was if the needle placed it there. The radiologist argued that the patient, against advice, had moved and bumped her breast, causing the movement. Regardless, I explained that this was a complication that could have been avoided if the parallel-to-the-chest-wall approach of needle localization was used (see Imaging Guided Needle Placement) instead of the free-hand approach. However, I pointed out that, given the fact that experts have taught the free-hand approach for years and have justified its use in the literature, this approach, it could be argued, was within the standard of care and could be defended. This is a case where, I believe, the standard of care was unnecessarily dangerous and not in the patient’s best interest.

and a wire was deployed. The next set of images show a wire traversing the breast to the chest-wall side of the film. The hook is beyond the edge of the film and is not visible on the images. It turns out that the wire ended up in the pericardium necessitating significant thoracic surgery, with the patient ending up in intensive care. On the surface this appears to be negligence. The only way the wire could have entered the pericardium was if the needle placed it there. The radiologist argued that the patient, against advice, had moved and bumped her breast, causing the movement. Regardless, I explained that this was a complication that could have been avoided if the parallel-to-the-chest-wall approach of needle localization was used (see Imaging Guided Needle Placement) instead of the free-hand approach. However, I pointed out that, given the fact that experts have taught the free-hand approach for years and have justified its use in the literature, this approach, it could be argued, was within the standard of care and could be defended. This is a case where, I believe, the standard of care was unnecessarily dangerous and not in the patient’s best interest.

Failure to Perceive an Abnormality

Finally, one of the most common problems that I have seen in suits against radiologists is for the failure to perceive a cancer that may or may not be visible, in retrospect, on a mammogram. Unfortunately, to the average juror it would seem simple. Either the cancer is visible, or not. Either it was missed, or not. As those who interpret mammograms know, the process is far from simple. The detection of all breast cancers by mammography is impossible, given that at least 5% to 15% of cancers are not visible, even in retrospect, on the mammogram. Furthermore, it is a well-established and unavoidable phenomenon that all observers periodically miss significant findings. Every radiologist, even the most expert in the field, occasionally fails to see an abnormality that, in retrospect, is evident on the film. This is true not only in the perception of cancer on a mammogram but has been documented in the review of chest x-rays for lung nodules (12,13), barium enemas for polyps, and bone films for fractures.

A radiologist must look at 1,000 studies, each containing at least 4 films (2 of each breast), to find between 1 and 10 cancers (depending on the age of the women screened and how frequently they are being screened). Every breast is unique in the appearance of its internal structures. It is not like a chest x-ray where everyone has a heart and ribs in the same place, and almost everyone has lungs in the same place. When reading a mammogram the radiologist is trying to look for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Sometimes the finding is clear and other times it is not. The task is complicated by the fact that benign changes can look like cancer, and cancers can have benign features. A truly fundamental problem is the fact that, as with any observational endeavor, radiologists are guaranteed to fail to perceive significant abnormalities periodically. It has been shown over and over again that even experts fail to recognize significant abnormalities on imaging studies at least as often as 30% of the time (14). Studies have shown that as many as 70% of breast cancers are visible in retrospect, but were overlooked, on a mammogram in the year, or even years, preceding the detection of the cancer (15).

Every radiologist who has spent more than a few years in the field will acknowledge that he/she has missed abnormalities on imaging studies that are visible, and even occasionally obvious, in retrospect. Are all radiologists negligent? Is this not a standard of care? How can someone, who has also missed cancers, condemn another for the same oversight when it is clearly an immutable human phenomenon? How can this be termed negligence? If all radiologists can be expected to fail to see a cancer that is visible in retrospect, then this is within the standard of care and should not be considered negligence (unless it can be shown that the error was, somehow, due to negligent behavior). Unfortunately, doctors can make a lot of money as experts by testifying that someone else should have seen a cancer.

The ability to perceive an abnormality is very complex. It is simple to relate to the problem. Every one of us has, at one time or another, looked for something familiar and not been able to find it, only to have someone else point to it in plain view. Looking for your keys in the morning is a common example. We are all expert in what our keys look like. We are focused and concentrating on looking for them. We are certainly not being negligent, yet we can look right at them and not see them, while someone else will point to them “right in front of your nose” (we even have a phrase that describes this common event). Is this negligence? This example seems to trivialize the interpretation of a mammogram, yet it is exactly what a radiologist does, only we do not know what the particular object looks like for which we are searching. Nor do we know that it “must be there,” as we do with our keys. This problem apparently affects every human involved in an observational endeavor, and it appears that there is no way of avoiding this periodic human frailty. If this is unavoidable, how can a radiologist be called negligent for being human?

When I have raised this issue at meetings, several lawyers have sanctimoniously invoked the stop sign analogy (leading me to wonder if this is a law school rationalization). They pointed out that missing a cancer on a mammogram is similar to failing to see a stop sign. There is certainly no excuse for driving through a stop sign, claiming that you did not see it. Superficially, this seems to be a compelling argument. However, it is really nonsensical and not a valid analogy. There are laws that pertain to stop signs. There are no laws that pertain to seeing a breast cancer. Stop signs all look the same, and there is no dispute as to their appearance. The same is not true for breast cancers. Stop signs are always found at intersections and, with few exceptions, are always on the right side of the road. I suspect that, if this

were not the case, we would be constantly failing to see these signs. Certainly, if the stop sign was hidden by trees or one encountered a stop sign only once in every 1,000 intersections, failing to stop would be defensible.

were not the case, we would be constantly failing to see these signs. Certainly, if the stop sign was hidden by trees or one encountered a stop sign only once in every 1,000 intersections, failing to stop would be defensible.

For those who remain skeptical, the following demonstration can be found on the Web (16). Count the number of Fs in the following text (this is not a trick question):

FINISHED FILES ARE THE RESULT OF YEARS OF SCIENTIFIC STUDY COMBINED WITH THE EXPERIENCE OF YEARS

Most observers will count three Fs in the paragraph. In fact, there are six Fs in the text. You are an expert in Fs. You were told that there are Fs in the text, you even suspected a trick, so you were extra diligent at looking, yet most everyone (who has not seen this before) will only see three Fs. Apparently, the brain does not process the Fs in the OFs. You have been provided with far more information than a radiologist has looking at a mammogram. You had a far simpler task to do, and you still missed three out of the six Fs. I would submit that it is not negligence when a human can look at something and not see it, since there is no way that we know of to prevent this from periodically happening. It is unfortunate but not negligence.

If we drop all of the sanctimonious pretense regarding our judicial system, we can acknowledge that it is probably one of the most fair in the world, but this does not mean that we cannot make it “more fair.” A mistake that I once made when discussing these problems with a lawyer was to suggest that our legal system was “designed to arrive at the truth.” He laughed and corrected me by pointing out that it was not designed to arrive at truth, but, as an adversarial system, it was designed to “see who wins.” Several, recent, highly visible cases have made this abundantly clear. The problem is that it is not just the legal system in isolation that is at stake. Complex scientific studies have shown that mammographic screening can reduce the death rate from breast cancer for women aged 40 and over by at least 30% (2). Studies in Sweden suggest that the potential for mammography to decrease the breast cancer death rate is as high as 63% (17). This is a dramatic change since the death rate from breast cancer in the United States had not changed in the 50 years preceding 1990. Since breast cancer screening began in the United States, in the mid-1980s, the breast cancer death rate has plunged. Mammographic screening can save a large number of lives. However, as noted earlier, as we begin to reduce the number of lives lost, we are facing an evolving crisis. Radiologists are shunning the interpretation of mammograms because of the fear of being sued for missing a cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree