The Bony Pelvis, Muscles and Ligaments

The pelvis ( Fig. 6.1 ) is a bony ring consisting of paired innominate bones , the sacrum and coccyx . The innominate bones articulate with each other anteriorly and with the sacrum posteriorly. Each innominate bone is composed of three parts – the ischium, ilium and pubis – which fuse at the acetabulum, at the Y-shaped triradiate cartilage , visible in the immature skeleton (see Fig. 8.9 ).

- 1.

Spinous process of L5 vertebra

- 2.

Transverse process of L5 vertebra

- 3.

Spinous process of the first sacral segment

- 4.

Lateral sacral mass

- 5.

Ilium

- 6.

Sacroiliac joint

- 7.

Sacral foramen of S2 vertebra

- 8.

Spinous process of S3 vertebra

- 9.

Coccyx: first segment of three

- 10.

Iliac crest

- 11.

Anterior superior iliac spine

- 12.

Anterior inferior iliac spine

- 13.

Pelvic brim

- 14.

Ischial spine

- 15.

Body of ischium

- 16.

Ischial tuberosity

- 17.

Ramus of ischium

- 18.

Inferior pubic ramus

- 19.

Body of pubic bone

- 20.

Pubic symphysis

- 21.

Superior pubic ramus

- 22.

Acetabulum

- 23.

Head of femur

- 24.

Fovea

- 25.

Neck of femur

- 26.

Greater trochanter of femur

- 27.

Lesser trochanter of femur

- 28.

Intertrochanteric femur

- 1.

Subcutaneous fat

- 2.

Rectus abdominis muscle

- 3.

Iliacus muscle

- 4.

Psoas muscle and tendon

- 5.

External iliac vein

- 6.

External iliac artery

- 7.

Inferior epigastric vessels

- 8.

Sartorius muscle

- 9.

Tensor fasciae latae muscle

- 10.

Gluteus minimus muscle

- 11.

Gluteus medius muscle

- 12.

Gluteus maximus muscle

- 13.

Piriformis muscle

- 14.

Obturator internus muscle

- 15.

Acetabulum

- 16.

Lower sacral segment: S4 vertebra

- 17.

Bladder: full of layering urine and contrast

- 18.

Perivesical fat

- 19.

Seminal vesicle

- 20.

Rectum containing air, faeces and contrast medium

- 21.

Wall of rectum

- 22.

Perirectal (mesorectal) fat

- 23.

Perirectal fascia (known as Denonvillier’s fascia anteriorly)

- 24.

Pararectal fat

- 1.

Pectineus muscle

- 2.

Obturator externus muscle

- 3.

Iliacus muscle

- 4.

Obturator internus muscle

- 5.

Pubic bone

- 6.

Ischial tuberosity

- 7.

Gluteus maximus muscle

- 8.

Levator ani

- 9.

Anus

- 10.

External anal sphincter

- 11.

Vagina

- 12.

Urethra surrounded by external urethral sphincter

- 13.

Sciatic nerve and inferior gluteal vessels

- 14.

Ischiorectal fossa

- 1.

Ischium

- 2.

Transverse perineal muscle

- 3.

Obturator internus

- 4.

Levator ani

- 5.

Attachment of levator to the tendinous arch of the fascia overlying the obturator muscle

- 6.

Body of the uterus

- 7.

Endometrial cavity

- 8.

Peritoneum reflected to the pelvic side wall

- 9.

Uterine vessels entering the broad ligament (deep to fascia)

- 10.

Internal iliac vessels

- 11.

Sigmoid colon

- 12.

Levator ani contributing to the external anal sphincter

- 13.

Sciatic nerve

- 14.

Ischiorectal fossa

The ilium is a flat curved bone and bears the iliac crest superiorly. The anterior and posterior superior iliac spines are on either end of the iliac crest, with the anterior and posterior inferior iliac spines below them. The inner surface of the bone is smooth and has a sharp crest at its base – the arcuate line – running from the sacroiliac joint to the iliopectineal eminence . This line extends anteriorly to the pubic tubercle as the anatomic iliopectineal line and delineates the inner margin of the pelvic inlet .

The pubic bone consists of a body , and inferior and superior rami . The body of the pubic bone articulates with its fellow at the symphysis pubis . It bears the iliopectineal eminence on its superolateral aspect and the pubic tubercle on its superomedial aspect. The iliopectineal line is a ridge on the superior pubic ramus. The articular surfaces of the symphysis pubis are covered in hyaline cartilage with a fibrocartilaginous disc between them. The pubic bone is strengthened on all sides by dense ligaments.

The ischium is composed of a body and an inferior ramus, which joins the inferior pubic ramus. The body bears the ischial tuberosity inferiorly and a spine posteriorly. The ischial spine defines the greater and lesser sciatic notches above and below.

The obturator foramen is bounded by the body and rami of the pubic bone and the body and ramus of the ischial bone.

PELVIC INLET

The pelvic inlet (also known as the pelvic brim or ring) is the division between the true and false pelvis. It passes through the anterior aspect of the sacral promontory and the upper part of the pubic symphysis. The arcuate and pectineal lines are visible as the iliopectineal line on plain radiographs (see Fig. 6.2 ).

The Sacrum

Five fused vertebrae comprise this triangular bone, which is curved posteriorly. The anterior part of its upper end is termed the sacral promontory. It articulates with the lumbar spine superiorly and with the coccyx inferiorly. Anteriorly the sacrum has four pairs of sacral foramina , which transmit nerves from the sacral canal . Lateral to these are the lateral masses or alae of the sacrum. The sacrum also bears four pairs of posterior sacral foramina and the canal ends posteriorly in the sacral hiatus – a midline opening that transmits the fifth sacral nerves.

The Coccyx

This is composed of three to five fused vertebrae. The first segment is often separate. It articulates at an acute angle with the sacrum.

The Sacroiliac Joints

The sacroiliac joints are covered with cartilage. The anterior aspect of the joint is lined with synovium. The joint surface is flat and uneven, and this irregularity helps lock the sacrum into the iliac bones. Ligaments support the front and back of the joint. There are dense interosseous sacroiliac ligaments (see Fig. 6.3 ) which further lock the sacrum to the iliac bones, limiting movement in all planes.

The sacrospinous ligament runs from the ischial spine to the sides of the sacrum and coccyx. It defines the inferior limit of the greater sciatic foramen .

The sacrotuberous ligament runs from the ischial tuberosity to the sides of the sacrum and coccyx. It defines the posterior limit of the lesser sciatic foramen .

The iliolumbar ligament runs from the transverse process of L5 to the posterior part of the iliac crest, further stabilizing the joint.

The pelvic muscles are shown in Figs. 6.4 and 6.5 . At the level of the iliac crest the paired psoas muscles lie on either side of the spine (see Fig. 6.4 ). They descend anteriorly, fusing with the iliacus muscle , which arises from the inner surface of the ilium. The fused iliopsoas muscle passes anteriorly under the inguinal ligament to insert into the lesser trochanter of the femur.

The aponeurosis of the abdominal wall muscles inserts into the superior surface of the pubic bone. A thickening of the aponeurosis is the inguinal ligament , which runs from the pubic tubercle to the anterior superior iliac spine. All the muscles of the anterior, lateral and posterior abdominal walls insert, to some degree, into the iliac crest, inguinal ligament and pubic bone.

The gluteal region is an anatomical area located posteriorly in the pelvic girdle. The muscles of the gluteal region move the lower limb at the hip joint and can be broadly divided into a superficial group that abducts and extends the femur and deep group that laterally rotates the femur (see Fig. 6.6 ).

Hip muscles: see Figs. 6.6 and 6.7 .

The superficial abductors and extenders comprise the glutei and tensor fascia lata (see Figs. 6.6 and 6.7 ).

The gluteus maximus is the largest, the most superficial and the most posterior gluteal muscle, covering the posterior part of the ilium and the sacroiliac joints. It arises from the posterior ilium, sacrum and coccyx, and inserts into the gluteal tuberosity of the femur. The gluteus medius and minimus are more anteriorly placed, the gluteus minimus being the smallest and the most deeply placed. Both originate from the gluteal surface of the ilium and insert into the greater trochanter; the gluteus medius inserts into the lateral part and the gluteus minimus inserts into the anterior part. The tensor fascia late is a small superficial muscle originating for the anterior superior iliac spine and inserts onto the lateral condyle of the tibia.

The deep lateral rotators comprise the piriformis, obturator internus, gemellus superior and inferior and quadratus femoris (see Figs. 6.6 and 6.7 ). These are smaller muscles that mainly rotate the femur laterally. They also stabilize and help to hold the femoral head in the acetabulum. The piriformis is the most superior and arises from the anterior surface of the sacrum. It travels inferolaterally through the greater sciatic foramen, inserting into the greater trochanter. The obturator internus forms the lateral wall of the pelvic cavity. It originates from the pubis and ischium around the rim of the obturator foramen as well as from the inner surface of the obturator membrane. It passes through the lesser sciatic foramen, inserting into the greater trochanter. The superior gemellus arises from the ischial spine and the inferior gemellus arises from the ischial tuberosity. The gemelli are two small triangular muscles and insert into the greater trochanter. The quadratus femoris is a flat, square muscle and is the deepest of the gluteal muscles, located below the obturator and gemelli muscles. It arises from the lateral side of the ischial tuberosity and inserts into the intertrochanteric crest of the femur.

RADIOLOGY OF THE PELVIC RING

Plain Films (see Fig. 6.2 )

Bony landmarks may be identified on plain radiograph (see Fig. 6.2 ). The sacral promontory and superior part of the pubic bone define the pelvic inlet and the iliopectineal line , running between and separating the true pelvis below from the false pelvis above. The sacroiliac joints are not optimally seen on the frontal view owing to their obliquity. Special views may be performed so that the X-ray beam passes through the joint to demonstrate it clearly.

Anomalous Lumbosacral Anatomy

Some variations of the lower lumbar spine and sacrum occur. The first sacral segment may be partially or completely separate – so-called lumbarization of the sacrum. Similarly, the lowest lumbar vertebra may be partially or completely fused to the sacrum – known as sacralization of the lumbar spine. The posterior elements of the lower lumbar vertebra or the sacral vertebrae may not be fused in some people, with no apparent sequelae.

In radiology reports it is important to identify disc levels clearly. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the usual convention is to count from the lowest disc. The lowest full disc level is designated L5/S1 even if there are six lumbar vertebrae. This must be clearly stated in the report.

Differences between the Male and Female Pelvis

- ■

The muscle attachments are more prominent in the male.

- ■

The pelvic inlet is heart-shaped in the male and oval in the female.

- ■

The angle between the inferior pubic rami is narrow in the male and wide in the female.

Cross-Sectional Imaging

The muscles of the pelvis may be seen on computed tomography (CT) and MRIs (see Figs. 6.6 and 6.7 ).

The Pelvic Floor

This is a sling of muscles and fascia attached to the pelvic bones that closes the floor of the pelvis (see Fig. 6.8 ). It provides static support of the pelvic and abdominal contents against gravity and increased intra-abdominal pressure. It also permits active control of the urethra and rectal sphincters, permitting both continence and evacuation. The urethra and rectum in the male, and urethra, vagina and rectum in the female, pierce the pelvic floor. The floor is composed of two muscular layers, the levator ani/coccygeus complex and the perineum .

The levator ani muscle is the principal support of the pelvic floor. It provides muscular support for the pelvic organs and reinforces the urethral and rectal sphincters (see Fig. 6.9 ). The levator ani arises in a line from the posterior aspect of the superior ramus of the pubis to the ischial spine. Between these bony points, the muscle arises from the fascia covering the obturator internus muscle on the inner wall of the ilium in an arc known as the tendinous arch or white line . Its fibres sweep posteriorly, inserting into the perineal body (a fibromuscular condensation behind the urethra in males and behind the urethra and vagina in females) (see Fig. 6.10 ), the anococcygeal body (a fibromuscular condensation between the anus and coccyx) and the lowest two segments of the coccyx. The midline raphe (fusion) of the levator ani anterior to the coccyx is also known as the levator plate . The fibres of the levator ani sling around the prostate gland or vagina and rectum, blending with the external anal sphincter . The components of the levator ani are named according to their attachments. Pubococcygeus , the main component, arises from the inner surface of the body of the pubis and the tendinous arch running posteriorly to the sacrum and coccyx. The puborectalis , the thickest and most medial aspect of the muscular sling, arises from the inner surface of the pubic bone and forms a sling behind the anorectal junction. The iliococcygeus is the posterior part of the muscle and runs from the posterior tendinous arch and the ischial spine to the coccyx.

- 1.

Bulb of penis

- 2.

Corpus cavernosum

- 3.

Perineal body

- 4.

External anal sphincter

- 5.

Puborectalis

- 6.

Adductor longus

- 7.

Adductor brevis

- 8.

Adductor minimis

- 9.

Obturator externus

- 10.

Gluteus maximus

- 11.

Inferior pubic ramus

- 12.

Ischioanal fossa

The coccygeus muscle is in the same tissue plane as the levator ani. It arises from the ischial spine and sacrotuberous ligament and inserts into the side of the coccyx and lower sacrum. It aids the levator ani in supporting the pelvic organs.

The perineum is the diamond-shaped space between the pubis, the ischial tuberosities and the coccyx. It is divided into two compartments by the transverse perineal muscles , which arise from the ischial tuberosity and run medially to insert into the perineal body.

The anterior compartment is the anterior urogenital triangle . The anterior urogenital triangle contains a tough sheet of fascia – the perineal membrane – which is pierced by the urethra and in females by the vagina as well. The external urethral sphincter is reinforced by this layer. Its inferior surface gives attachment to the bulb and crura of the penis or clitoris ( bulbocavernosus and ischiocavernosus ).

The posterior compartment is the anal triangle . It contains the anus and its sphincters, with the ischiorectal fossa on either side. The ischiorectal fossa is the space below and lateral to the posterior part of the levator ani and medial to the inner wall of the pelvis. It is bounded posteriorly by sacrotuberous ligaments and the gluteus maximus muscle, laterally by the fascia of the obturator internus muscle and anteriorly by the perineal body. It contains mainly fat and is of importance in pathological conditions of the rectum. The anococcygeal body extends from the anus to the coccyx posteriorly. It receives fibres from the anal sphincter and levator ani muscles.

The perineal body (see Fig. 6.10 ) is a pyramidal fibromuscular structure that is widest inferiorly. It lies between the anus and bulb of the penis in males and between the anus and posterior vagina in females. It is important in maintaining the integrity of the pelvic floor, especially in females. The perineal body is the central crossroad for the intersection of different layers of fascia and muscle insertions. All layers of pelvic floor muscles – the bulbospongiosus, the superficial transverse perineal muscles, external anal sphincters, and the puborectalis and fibres from the external urethral sphincter – insert into this structure.

RADIOLOGY OF THE PELVIC FLOOR

Imaging of the pelvic floor is mostly required for evaluation of excessive pelvic floor laxity, leading to problems with urinary and bowel continence and rectal evacuation. This is most common in women as a result of childbirth injury.

Dynamic Proctography

Indirect imaging of the rectal floor is possible with defecating proctography, where the rectum, bladder and vagina are outlined with contrast and the subject is imaged in the lateral plane. Images are obtained at rest, during a ‘clenching’ or ‘Kegel’ manoeuvre to elevate the pelvic floor and during straining/evacuation to evaluate pelvic floor movement and the dynamics of rectal evacuation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (see Figs. 6.10, 6.11 )

The muscles of the pelvic floor can be directly imaged by MRI. Pelvic floor movement can be assessed dynamically (see section on dynamic MRI).

- 1.

Anterior wall of vagina

- 2.

Posterior wall of vagina

- 3.

External urethral sphincter

- 4.

Anal canal

- 5.

External anal sphincter

- 6.

Puborectalis

- 7.

Obturator internus

- 8.

Obturator externus

- 9.

Pectineus

- 10.

Gluteus maximus

- 11.

External iliac vessels

- 12.

Ischioanal fossa

- 13.

Pubic symphysis

- 14.

Coccyx

- 15.

Ischial tuberosity

The Sigmoid Colon, Rectum and Anal Canal

THE SIGMOID COLON

The sigmoid colon is extremely variable in length (12–75 cm, average 40 cm). It is covered by a double layer of peritoneum, supported on its mesentery, which is attached to the posterior and left lateral pelvic wall. It has the same sacculated pattern as the rest of the colon in young people. In older subjects it may appear featureless. The redundant sigmoid lies on the other pelvic structures.

- 1.

Rectum

- 2.

Mesorectal fat

- 3.

Mesorectal fascia

- 4.

Peripheral zone prostate

- 5.

Transition zone prostate

- 6.

Bladder

- 7.

Spermatic cord

- 8.

External iliac artery

- 9.

External iliac vein

- 10.

Obturator internus

- 11.

Lower fibres piriformis

- 12.

Pectineus

- 13.

Iliopsoas

- 14.

Rectus abdominus

- 15.

Gluteus maximus

- 16.

Femoral head

- 17.

Acetabulum

- 18.

Coccyx

- 19.

Coccygeus

- 1.

Rectum

- 2.

Anal canal

- 3.

Internal anal sphincter

- 4.

External anal sphincter

- 5.

Levator ani

- 6.

Puborectalis

- 7.

Obturator internus

- 8.

Mesorectal fat

- 9.

Mesorectal fascia

- 10.

Internal iliac vessels

- 11.

Iliac bone

- 12.

Sacroiliac joint

- 13.

Sciatic nerve

- 14.

Transverse perineal muscles

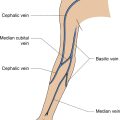

Blood Supply ( Figure 5.24 , Figure 5.25 )

Arterial supply is from the inferior mesenteric artery via the sigmoid arteries, which join in the arterial cascade of the large bowel. Venous drainage is to the portal system via the inferior mesenteric vein.

Lymph Drainage

This is via the blood supply to preaortic nodes around the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery.

THE RECTUM ( Figs. 6.12, 6.13 )

The rectum is about 12 cm long. It commences anterior to S3 and ends in the anal canal 2–3 cm in front of the tip of the coccyx. It forms an anteroposterior (AP) curve in the hollow of the sacrum. The rectum has no sacculations or mesentery. Its upper third is covered by peritoneum on its front and sides; its middle third has peritoneum on its anterior surface only, and its lower third has no peritoneum. The lower part of the rectum is dilated into the rectal ampulla. In the resting state, the mucosa of the rectum has three to four longitudinal mucosal folds, known as the columns of Morgagni . The taenia coli fuse in the rectum. Some longitudinal shortening of the rectum occurs, giving the rectum a slight S shape. This creates three transverse mucosal folds – left, right and left from above downward. These are known as the valves of Houston . The lowest part of the rectum, known as the ampulla, relaxes to store faeces until defecation occurs.

Posteriorly are the sacrum and coccyx. Anteriorly, loops of small bowel and sigmoid colon lie in the peritoneal cul-de-sac between the upper two-thirds of the rectum and the bladder or uterus. The lower third is related to the vagina in the female and to the seminal vesicles, prostate and bladder base in the male.

The rectum is surrounded by perirectal fat . Fascia known as the perirectal fascia surrounds the perirectal fat, and lateral to the perirectal fascia is the pararectal fat . The perirectal fascia separates the seminal vesicles and prostate from the rectum anteriorly.

Mesorectal Fascia (see Fig. 6.13 )

The mesorectal fascia is a continuation of the fascia of the sigmoid colon at the rectosigmoid junction and surrounds the rectum and perirectal fat, from the origin of the rectum to its lower end at the levator ani. The mesorectal fascia is continuous anteriorly with the rectovesical fascia (Denonvilliers fascia), separating rectum from bladder, seminal vesicles and prostate. Posteriorly it is fused with the presacral fascia (Waldeyer fascia). The mesorectum is perirectal fat surrounding the rectum and carries the vessels and nerves that supply it. It is delineated by the mesorectal fascia.

The mesorectum and mesorectal fascia can be recognized on MRI. In rectal cancer surgery, the fascia forms the surgical resection margin, which aims for total mesorectal excision. Distance of tumour from the fascia is of prognostic significance.

THE ANAL CANAL ( Fig. 6.14 )

This is directed posteriorly almost at right angles to the rectum. It is a narrow, muscular canal. It has an internal sphincter of involuntary muscle and an outer external sphincter of voluntary muscle , which blends with the levator ani. The internal (smooth muscle, involuntary) sphincter occupies the upper two-thirds of the anal canal. The external (striated, voluntary) sphincter occupies the lower two-thirds. Thus, the sphincters overlap in the middle third, with the internal deep to the external. The junction of the rectum and anal canal is at the pelvic floor where the puborectal sling encircles it, causing its anterior angulation.

- 1.

Endoanal probe

- 2.

Thin bright (echogenic) line is mucosal surface interface

- 3.

Subepithelial tissue deep to mucosa – intermediate signal

- 4.

Dark (hypoechoic) line is internal anal sphincter

- 5.

Thin bright (echogenic) line is longitudinal muscle outside the internal anal sphincter

- 6.

Intersphincteric space

- 7.

Striated intermediate signal thick outermost layer is external anal sphincter

Anteriorly, the perineal body separates the anus from the vagina in the female and the bulb of the urethra in the male. Posteriorly, the anococcygeal body is between it and the coccyx, and laterally is the ischiorectal fossa.

The anal canal is lined by mucous membrane in its upper two-thirds and by skin in its lower third. The mucosa of the anal canal has several vertical folds.

Radiology of the Anal Canal (see Figs. 6.13, 6.14 )

MRI, with its excellent soft-tissue resolution, is the imaging modality of choice for anal and perianal abnormalities.

The internal and external sphincters can be identified with the intersphincteric space between them. Images are obtained in the coronal plane and at right angles to the anal canal.

Endoanal ultrasound ( Fig. 6.14B ) is used to assess the integrity of the sphincters, mainly in the investigation of obstetric injuries. The internal and external sphincters, transverse perineal muscles and puborectalis can be evaluated longitudinally and axially at upper mid- and lower anal canal levels. The test can be combined with endoanal physiology using a pressure-sensitive catheter to assess pressures at rest and during squeezing and bearing-down manoeuvres. In the upper (proximal) anal canal, the U-shaped fibres of the puborectalis muscle may be identified sweeping posteriorly. At mid-anal canal level, where the internal anal sphincter (IAS) and external anal sphincter (EAS) overlap, the following layers can be identified from inside out: the echogenic mucosa, the intermediate signal subepithelial layer (submucosa), the hypoechoic internal anal sphincter, a thin higher signal longitudinal muscle layer outside the IAS, the intersphincteric space outside the longitudinal muscle and the striated EAS outermost. At mid-canal level, the EAS forms a complete ring. At distal anal canal level, the IAS has terminated and only the EAS is seen. At this level the EAS does not form a complete ring.

The mucocutaneous junction is known as the dentate line or Hilton’s white line. This defines a division between arterial supply and venous and lymphatic drainage.

Owing to the posterior angulation of the anal canal from rectum to skin, insertion of an endorectal ultrasound probe should be inserted with a slight anterior angulation, to follow the line of the anal canal.

Blood Supply ( Figs. 6.15, 6.16 )

The superior, middle and inferior rectal (haemorrhoidal) arteries form a rich submucous plexus supplying the rectum and anal canal. The superior rectal artery is a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. The middle and inferior arteries arise from the internal iliac artery. The plexus drains via a superior rectal vein to the inferior mesenteric vein and via middle and inferior veins to the internal iliac vein. This represents communication between the systemic and portal systems.

- 1.

Abdominal aorta

- 2.

Lumbar artery

- 3.

Right common iliac artery

- 4.

Left common iliac artery

- 5.

Left external iliac artery

- 6.

Left internal iliac artery

- 7.

Inferior mesenteric artery

- 8.

Median sacral artery

- 9.

Posterior trunk of right internal iliac artery

- 10.

Iliolumbar artery (branch of 9)

- 11.

Lateral sacral artery (branch of 9)

- 12.

Superior gluteal artery (branch of 9)

- 13.

Anterior trunk of right internal iliac artery

- 14.

Obturator artery (branch of 13)

- 15.

Vesical artery (branch of 13)

- 16.

Inferior gluteal artery (branch of 13)

- 17.

Deep circumflex iliac artery

Lymph Drainage

The rectum and upper anal canal drain to pararectal nodes . Lymph from the upper rectum drains to preaortic nodes around the inferior mesenteric artery and from the lower rectum to internal iliac nodes. The lower anal canal drains to superficial inguinal nodes.

RADIOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID AND RECTUM

Plain Films (see Fig. 5.2 )

The sigmoid colon and rectum may be identified on plain radiographs outlined by air, faeces or both. The sigmoid colon has a characteristic S-shaped curve as it joins the descending colon to the rectum, which lies anterior to the sacrum.

CT Colonography

The cleansed colon is insufflated with gas (CO 2 ) to achieve gaseous distension of the entire colon. Ingestion of a cup of contrast such as gastrografin the day before the scan coats residual stool and differentiates it from polyps (faecal tagging). This technique allows examination of the mucosa for polyps through a number of viewing techniques, including surface-rendered imaging, in which the interface between mucosa and air in the lumen is electronically rendered into a surface image of the lumen.

Computed Tomography

The rectum and perirectal tissues are readily assessed by CT. Detail is considerably enhanced by administration of intravenous contrast. The rectal wall, perirectal fat and fascia and pararectal fat may be identified. Images may be reconstructed in multiple planes.

Contrast Enema (see Fig. 5.23 )

The best detail is achieved by using a double-contrast barium technique. A small amount of thick barium is used to coat the mucosa, followed by sufficient air or gas to distend the bowel. The patient is rotated to allow the barium and gas to reach and coat all regions of the colon from the rectum to the tip of the caecum. Various projections are required to open up the overlapping loops satisfactorily, especially sigmoid colon, splenic and hepatic flexures. This ensures adequate views of all the large bowel. The valves of Houston are the transverse mucosal folds or indentations of the rectum seen on an anterior view and are usually less than 5 mm thick. The appendix may be seen as a long, blind-ending structure in the right iliac fossa if it fills (50%–70%). Above the appendix, an indentation from the ileocaecal valve may be identified on the medial wall of the right colon. This demarcates the transition from caecum to ascending colon. The longitudinal columns of Morgagni are best identified after evacuation of barium, when the rectum is not distended. These normally measure 3 mm in width. The posterior impression of the pubococcygeal fibres of levator ani may be identified at the lower limit of the rectum. The anal canal may be identified if outlined with contrast after removal of the enema catheter; it makes an acute, posteriorly directed angle with the rectum (see also Chapter 5 ).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging ( Fig. 6.13 )

MRI is highly useful for assessing stage and evaluating the mesorectal fat in rectal tumours, both for operative planning and to assess response to chemoradiation. The anal sphincter can also be evaluated for pathology such as perianal inflammatory conditions leading to fistulae and sinus tracts. It is important to image parallel to and at right angles to the plane of the structure being imaged. The rectum or anal canal are first identified on sagittal images. Coronal and axial images of the rectum and anal canal can then be acquired perpendicular and parallel to the structure being imaged. High-resolution T2 images are best for anatomy detail.

Heavily T2-weighted sequences that saturate fat (fat becomes dark) and show fluid as bright signal are used to demonstrate sinus tracts and fistulae from the anal canal using a clock face terminology to describe their anal origin (12 o’clock being anterior midline and 6 o’clock being posterior midline).

Dynamic Imaging ( Fig. 6.17 )

The rectum can be evaluated dynamically during straining or evacuation with dynamic MRI or barium defecography. During defecation, the rectum and anus descend with the pelvic floor and the acute anorectal angle increases (straightens out) as contrast material is evacuated. During contraction of the pelvis the rectum and anus ascend, the anorectal angle narrows and a posterior impression is seen at the lower end of the rectum owing to the action of puborectalis.

Blood Vessels, Lymphatics and Nerves of the Pelvis

OVERVIEW OF THE ARTERIES AND VEINS

The aorta bifurcates at the level of L4 slightly to the left of midline. At the level of the iliac crest the common iliac arteries are slightly anterior to the common iliac veins. Both vessels are located on the medial border of the psoas muscle as this passes anteriorly into the pelvis. The vessels pass behind the distal ureters. At the level of the pelvic inlet the internal iliac vessels run medially and posteriorly towards the sciatic notch, and the external iliac vessels continue down on the medial aspect of the iliopsoas muscle, passing under the inguinal ligament to enter the thigh.

INTERNAL ILIAC ARTERY ( Figs. 6.15, 6.16 )

This artery arises in front of the sacroiliac joint at the level of L5–S1 or the pelvic inlet. It descends to the sciatic foramen and divides into an anterior trunk, which continues down towards the ischial spine, and a posterior trunk, which passes back towards the foramen. Anterior to the internal iliac artery are the distal ureters, and in the female the ovary and fallopian tube. The internal iliac vein is posterior and the external iliac vein and psoas muscle are lateral. Peritoneum separates its medial aspect from loops of bowel.

Branches of the Anterior Trunk

These are as follows:

- ■

Umbilical artery : Before birth, this carries blood from the internal iliac artery to the placenta. It is obliterated after birth to become the medial umbilical ligament and usually gives rise to one or several superior vesical arteries .

- ■

Obturator artery: Passes anteriorly through the obturator foramen.

- ■

Inferior vesical artery (male) or uterine artery (female): Supplies the seminal vesicles, prostate and fundus of the bladder in the male. In the female, the uterine artery runs medially in the broad ligament to supply the uterus, cervix and fallopian tubes, with branches to the ovary and vagina.

- ■

Middle rectal artery : To inferior rectum with branches to the seminal vesicles, prostate or vagina.

- ■

Inferior gluteal artery : Passes through the greater sciatic foramen to supply muscles of the buttock and thigh.

- ■

Internal pudendal artery : Passes through the greater sciatic foramen and curves around the ischial spine or sacrospinous ligament to re-enter the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen, thence running anteriorly in the lateral aspect of the ischiorectal fossa. It passes through the pudendal canal (a fascial sheath derived from the obturator internus) in the lateral wall of this fossa, exiting the pelvis medial to the ischial tuberosity to form the dorsal and deep arteries of the penis or clitoris.

Branches of the Posterior Trunk

These are as follows:

- ■

Iliolumbar artery : This ascends in front of the sacroiliac joint. It supplies the psoas and iliacus muscles and gives a branch to the cauda equina.

- ■

Lateral sacral arteries : Usually two. These pass through the anterior sacral foramina and exit through the posterior sacral foramina. They supply the contents of the sacral canal and muscle and skin of the lower back.

- ■

Superior gluteal artery : A continuation of the posterior trunk. This passes through the greater sciatic foramen to supply the muscles of the pelvic wall and gluteal region.

EXTERNAL ILIAC ARTERY ( Fig. 6.16 )

This runs downwards and laterally on the medial border of the psoas muscle to a point midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. At this point it passes under the inguinal ligament to become the common femoral artery. In front of and medial to the vessel, the peritoneum separates it from loops of bowel. Its origin may be crossed by the ureter. In the female it is crossed by the ovarian vessels. In the male it is crossed by the testicular vessels and the ductus deferens. The external iliac vein is posterior to its upper part and medial to its lower part.

Branches of the Iliac Artery

Both branches arise just above the inguinal ligament and are as follows:

- ■

Inferior epigastric artery: This runs superiorly on the posterior surface of anterior abdominal wall to enter the rectus sheath.

- ■

Deep circumflex iliac artery: This ascends laterally to the anterior superior iliac spine behind the inguinal ligament and passes back on the inner surface of the iliac crest, supplying the abdominal wall muscles.

- •

The umbilical artery is the first branch of the internal iliac artery in the fetus (in fact, it is a continuation of the internal iliac artery). In the fetus, the paired umbilical arteries ascend on the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall to the umbilicus and into the cord, where they then coil around a single umbilical vein. After birth the umbilical arteries persist as fibrous cords covered by folds of peritoneum known as the medial umbilical ligaments . They may be identified if outlined by air on plain radiograph as in pneumoperitoneum and can also be identified on CT.

- •

The lateral umbilical ligaments are the folds of peritoneum covering the inferior epigastric arteries as they run from the external iliac arteries to enter the posterior aspect of the rectus sheath muscle. See below for the median umbilical ligament .

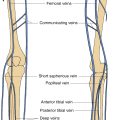

THE ILIAC VEINS (see Fig. 6.6 )

The external and internal iliac veins accompany the arteries. At the groin, the veins lie medial to the arteries. As the veins ascend, they become posterior to the arteries. The upper part of the left common iliac vein then passes to the right behind its artery to form the inferior vena cava by joining with its fellow to the right of and slightly posterior to the aortic bifurcation.

The tributaries of the iliac veins match the arterial branches, except for the gonadal (ovarian and testicular) veins. These drain to the left renal vein on the left and directly to the inferior vena cava on the right.

RADIOLOGY OF THE ILIAC VESSELS ( Fig. 6.16 )

Conventional Angiography

In conventional angiography contrast medium is injected under high pressure into the distal aorta via a pigtail catheter, which is inserted retrogradely through a common femoral artery. Images may be acquired using plain radiographs or using digital subtraction angiography, where information is acquired on an image intensifier and processed by computer.

CT Angiography

CT following the administration of intravenous contrast gives excellent cross-sectional information about the vessels in the pelvis and their relationship to surrounding structures. Acquisition of images is timed to optimize the contrast opacification of the vessels being imaged. The arteries have a round, even calibre whereas the veins are usually larger and more oval-shaped in the supine position. Reconstructions in coronal, sagittal and various oblique planes may be performed on the raw data to display the vessels optimally.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI of the iliac vessels can be performed without contrast, although contrast images are diagnostically superior. The vessels may be imaged in any plane.

Venography

The veins are identified on cross-sectional contrast imaging. Direct contrast opacification of the internal iliac veins would require intraosseous injection of contrast into the bodies of the pubic bones.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound may also identify the common and external iliac vessels, although visualization is somewhat dependent on unpredictable factors such as bowel gas and body habitus of the subject. The vessels are seen as anechoic linear structures. Colour and pulsed-wave Doppler techniques demonstrate the direction of blood flow and facilitate identification.

THE LYMPHATICS

Lymph drainage runs in lymphatic channels related to the blood vessels. Three chains accompany the external iliac vessels – one (antero)lateral to the artery, one (postero)medial to the vein, and a variable middle chain anteriorly between the vessels. The obturator node is part of the middle chain. These chains drain to the common iliac and para-aortic nodes. The internal iliac lymph vessels and nodes drain to nodes around the common iliac and from here superiorly to the para-aortic nodes. Sacral nodes drain to the internal chain.

RADIOLOGY OF THE LYMPHATICS

Lymphangiography

Direct lymphangiography can be performed using an oily contrast agent (Lipiodol) which is imaged with fluoroscopy. Lymphangiography is the only radiological method available for direct demonstration of the lymphatics, and the technique has been adapted to allow visualization of the lymphatics on MRI, for example in the study of lymphedema. Lymphatics in the foot can be identified by injecting a blue dye into the web spaces of the toes. A ‘blue’ lymphatic vessel is cannulated with a very fine cannula and lipiodol contrast injected for direct fluoroscopic imaging. A gadolinium agent may be injected for MR lymphography. The external iliac, obturator, common iliac and para-aortic nodes can be demonstrated. The internal iliac nodes are not visualized using this method as lymph from the lower limb does not drain to the internal iliac nodes (see also lymphography in Chapter 5 ).

Cross-Sectional Imaging

Lymph nodes are visible on ultrasound, CT and MRI, especially when over 5 mm. Lymph nodes enhance after contrast, aiding their visibility. In a normal node, the cortex should be smooth and uniform, and is usually less than 3 mm. Although a lymph node can be over 2 cm in length, its short-axis measurement should not be more than 1 cm in the abdomen and pelvis. A normal lymph node typically has a fatty hilum and a uniform cortical thickness. Measurements on cross-sectional imaging are always made on the short axis.

In MRI, sequences that suppress fat signal allow easier identification of nodes on conventional MRI. In a further refinement, injected super magnetic iron oxide particles (USPIO) accumulate in the normal reticuloendothelial structure of the lymph nodes, causing them to appear dark (due to iron) on MRI.

IMPORTANT NERVES OF THE PELVIS

The anterior divisions (rami) of the nerve roots from L1 to S3 form the lumbosacral plexus of nerves. The rami divide into several cords which then combine to form the peripheral nerves to the pelvis and lower limbs. The lumbar plexus is formed within the psoas muscles and anterior to the transverse processes by the anterior divisions (rami) of L1–L4. The sacral plexus is formed by the anterior divisions of L4–S3 on the sacrum and piriformis muscle. The lumbar plexus is joined to the sacral plexus by the fourth and fifth anterior lumbar roots, which combine to form the lumbosacral trunk.

The femoral , sciatic , obturator and pudendal nerves pass through the pelvis to supply the lower limb. They are formed by the union of various cords of the lumbosacral plexus of nerves.

The obturator nerve (ventral divisions of anterior rami of L2–L4 nerves) descends through and emerges medial to the psoas muscle, runs along the lateral pelvic wall and through the upper part of the obturator foramen into the thigh. It passes behind the common iliac vessels to lie posteromedial to the common iliac vein in the pelvis. It provides sensory innervation of the medial thigh and motor innervation of some of the anterior and medial thigh muscles.

The femoral nerve (dorsal divisions of anterior rami of the L2–L4 nerves), surrounded by fat, descends through the psoas, emerging between the psoas and iliacus muscles, passing under the inguinal ligament into the thigh and dividing into anterior and posterior divisions. It is separated from the femoral artery under the inguinal ligament by a portion of psoas muscle. It supplies the skin and muscles in the anterior thigh.

The sciatic nerve (see Fig. 6.7 ) is the largest in the body. It is formed from the lumbosacral plexus on the anterior surface of the sacrum and piriformis from ventral divisions of L4–S3. It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle into the gluteal region, then runs down into the back of the thigh. It supplies most of the skin of the leg, the posterior thigh muscles and muscles of the lower leg and foot.

The pudendal nerve arises from the ventral divisions of S2–S4. It passes between the piriformis and coccygeus, and exits the pelvis through the lower part of the greater sciatic foramen. It then hooks around the ischial spine/sacrospinous ligament and re-enters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen, running anteriorly in the lateral aspect of the ischiorectal fossa on the medial surface of the obturator internus muscle. It is accompanied by the pudendal artery and vein in a sheath of obturator fascia called the pudendal canal . It supplies the external genitalia in both sexes as well as the urethral and anal sphincters.

Nerves to the organs of the pelvis are also derived from the lumbosacral plexus.

RADIOLOGY OF THE NERVES OF THE PELVIS

The nerves of the pelvis can be identified along with their vessels in CT and MRI. Thin-section, high-resolution images with fat saturation in the coronal plane are used to demonstrate the lumbosacral plexus.