Thoracic Radiology

Lejla Aganovic

Timothy Singewald

James G. Ravenel

The authors and editors acknowledge the contribution of the Chapter 7 author from the second edition: Caroline Chiles, MD.

Case 9.1

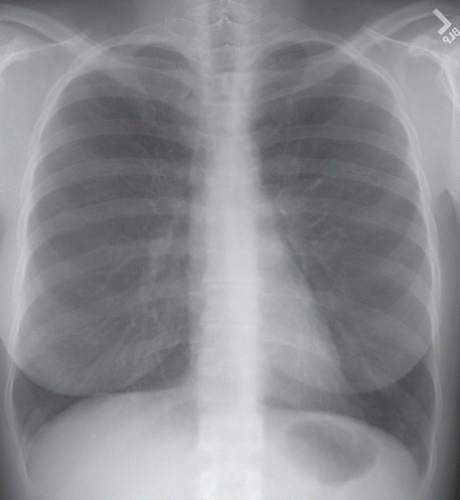

HISTORY: A 25-year-old woman with recurrent pneumonia

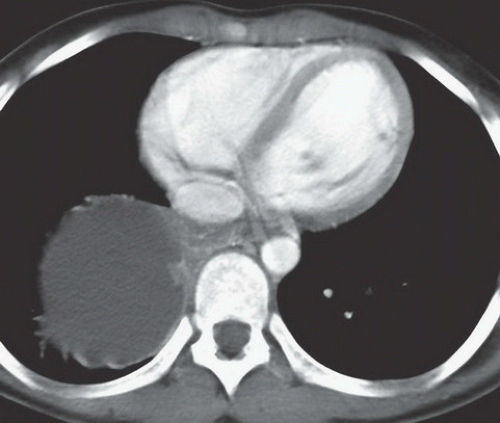

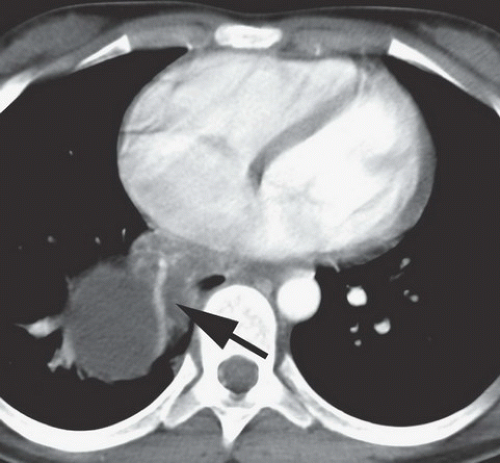

FINDINGS: A part-solid and cystic mass is visible in the posterior basal segment of the right lower lobe on contrast-enhanced CT (Figs. 9.1.1 and 9.1.2) of the chest. There is a large systemic vessel coursing through the mass (Fig. 9.1.2, arrow).

DIAGNOSIS: Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration

DISCUSSION: Bronchopulmonary sequestration is a rare pulmonary lesion in which a portion of lung is set apart from the rest of the lung and receives systemic arterial supply. There are two types of sequestration: intralobar and extralobar. Characteristics of intralobar sequestration include systemic arterial supply and pulmonary venous drainage from a portion of lung with no connection to the tracheobronchial tree, whereas an extralobar sequestration has a separate pleural covering, systemic arterial supply, and systemic venous drainage (1). Some believe that some intralobar sequestrations may be acquired rather than congenital lesions given that they are typically detected incidentally and at an older age than extralobar sequestration. Approximately 50% intralobar sequestrations are diagnosed before the age of 20 and the diagnosis is seldom reported after the age of 40 (2).

It is most common for the intralobar sequestrations to occur in the posterior basal segments of the lower lobes. Although the systemic supply is usually from the aorta, arteries to an intralobar sequestration may arise from the diaphragm, chest wall, or abdomen. Typical radiographic features include focal consolidation that may contain cystic areas or gas. In addition, there may be emphysema distal to the lesion (1). In most cases the systemic arterial supply is identifiable although CT angiography may be necessary to document the course and location of the vessel.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration has systemic arterial supply and pulmonary venous drainage and may be discovered as an incidental finding.

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration has a pleural covering, systemic arterial supply, and systemic venous drainage—usually in left lower lobe and generally associated with other congenital anomalies.

Case 9.2

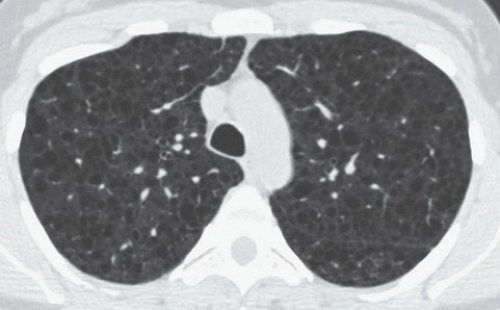

HISTORY: A 64-year-old farmer with shortness of breath

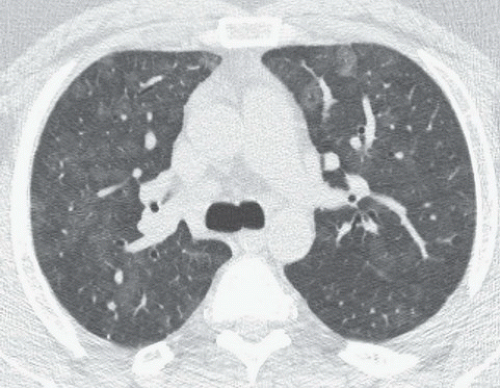

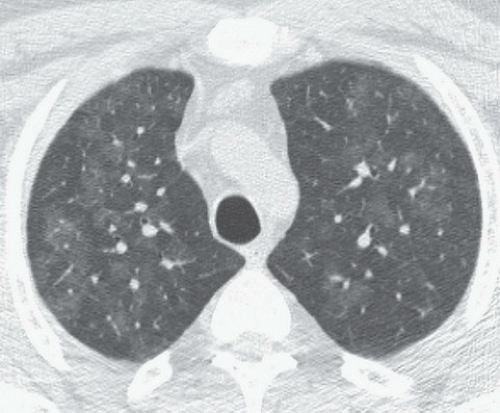

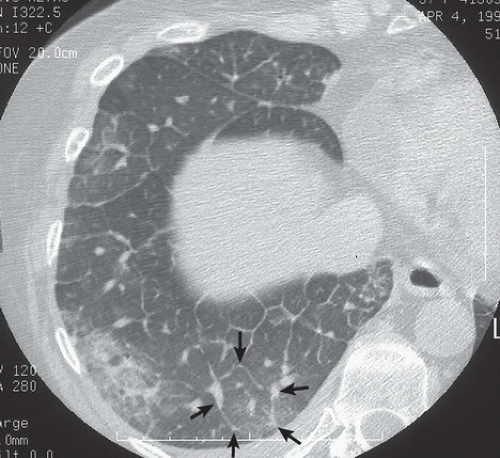

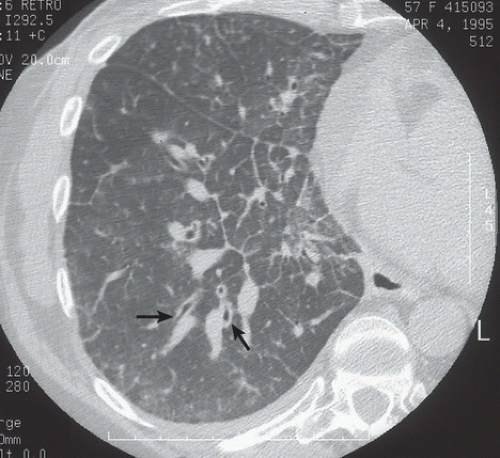

FINDINGS: Axial high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) images (Figs. 9.2.1 and 9.2.2) through chest demonstrate multiple ill-defined centrilobular nodules throughout the lungs.

DIAGNOSIS: Subacute hypersensitive pneumonitis

DISCUSSION: Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an allergic lung disease caused by inhalation of antigens contained in a variety of organic dusts (3). Radiographic and pathologic abnormalities that are seen in patients with hypersensitive pneumonitis (HP) are quite similar, regardless of the organic antigen responsible. These abnormalities can be classified into acute, subacute, and chronic stages. In the acute phase diffuse ill-defined airspace consolidation can be seen on chest radiograph and chest CT. After resolution of acute abnormalities a fine nodular pattern is often visible on radiographs. Typical findings of subacute HP on HRCT include patchy ground-glass opacities, small ill-defined centrilobular nodules, or both (4). The nodules are typically smaller than 4 mm and involve all lung zones to a similar extent with relative sparing of the fissures and pleural surfaces. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis is characterized by the presence of fibrosis, although findings of active disease may also be present. Findings in fibrosis include intralobular interstitial thickening, irregular interfaces, irregular interlobular septal thickening, honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Diffuse centrilobular nodules in a person exposed to organic dust are characteristic of subacute hypersensitive pneumonitis.

Nodules of subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis typically spare the periphery of the lung.

Case 9.3

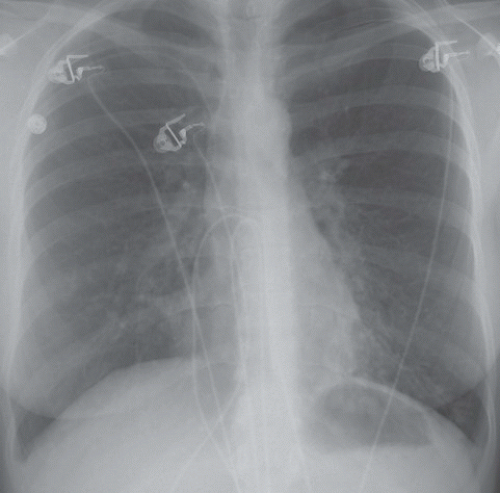

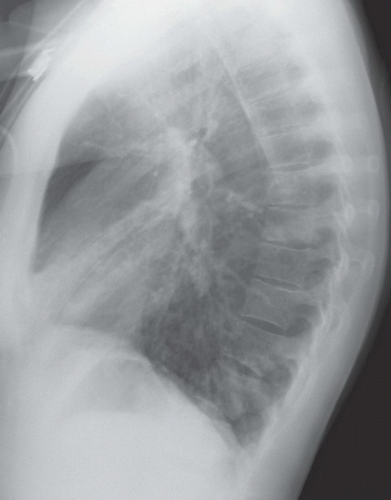

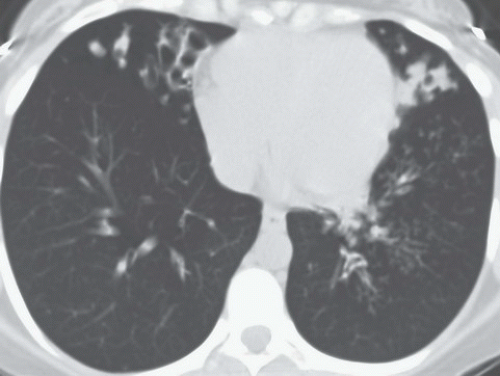

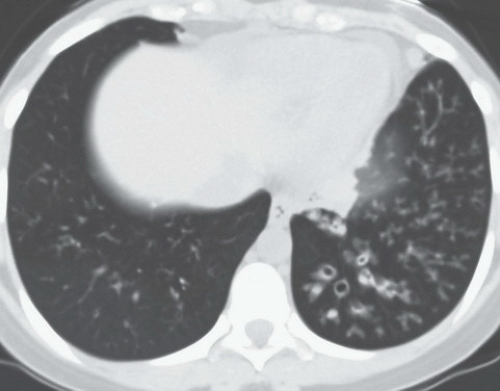

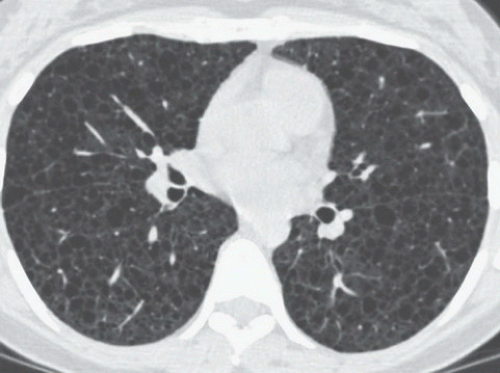

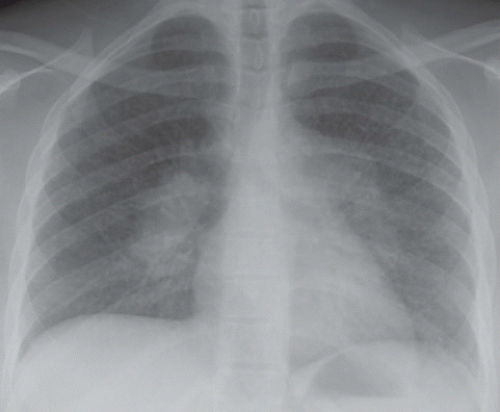

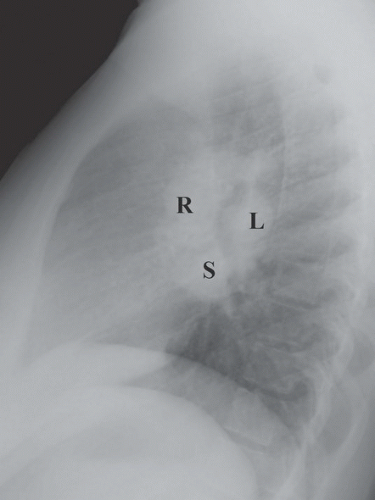

HISTORY: A 23-year-old woman with chronic cough

FINDINGS: Posteroanterior (PA; Fig. 9.3.1) and lateral (Fig. 9.3.2) views of the chest show coarse tubular opacities at both lung bases. The CT reveals varicoid and cystic bronchiectasis within the right middle lobe and lingula (Fig. 9.3.3) and left lower lobe (Fig. 9.3.4) associated with branching tubular opacities (mucoid impaction) and air trapping.

DIAGNOSIS: Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD)

DISCUSSION: PCD is primarily an autosomal recessive inherited disorder that includes a heterogeneous group of ultrastructural defects involving the axoneme or central functional element of the cilia. Functionally, these disturbances result in reduced or disorganized beating of the ciliated epithelial cells or, in some cases, complete immotility. The ineffectual beating or immotility of cilia results in accumulation of mucus resulting in recurrent infections of the upper and lower respiratory tracts (5). In some cases there is inversion of the normal anatomic structures of the thorax and abdomen, situs inversus universalis, or partialis; PCD with situs inversus universalis is known by the eponym, Kartagener syndrome.

Bronchiectasis is a common sequela of PCD, typically involving the dependent zones including the lower lobes, right middle lobe, and/or the lingular segments of the left upper lobe. Chest radiographs may demonstrate overinflation, bronchial wall thickening, and bronchial dilation. Bronchiectasis can be quite subtle on conventional radiographs and may appear as parallel linear CT demonstrates bronchiectasis, that is often varicoid or cystic in the lower lobes, with or without right middle lobe or lingular involvement and relative sparing of the upper lobes (6).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Bronchiectasis in PCD is basal predominant, distinguishing it from the typical pattern seen in cystic fibrosis.

Case 9.4

HISTORY: Mass on chest x-ray

FINDINGS: Right upper lobe mass with finger-like projections superiorly (Fig. 9.4.1, arrows). CT images (Fig. 9.4.2) reveal a V-shaped tubular mass with distal air trapping (arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Congenital bronchial atresia

DISCUSSION: Bronchial atresia is an uncommon congenital anomaly that is usually detected as an incidental finding in adults. The apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe is most commonly affected followed by the right upper lobe, middle lobe, and lower lobes (7,8). The lung develops normally in a position distal to the atretic bronchus and is ventilated by collateral air drift (8,9). Airways distal to the atretic segmental bronchus continue to produce mucus, which leads to mucoid impaction or mucocele formation within the bronchus. The affected lobe appears hyperaerated and is both oligemic and hyperlucent (8,9). Bronchial atresia is generally asymptomatic and requires no further treatment although it should be distinguished from obstructing neoplasm.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Findings of bronchial atresia result from mucoid impaction distal to atretic bronchus and hyperexpanded lobe; usually apicoposterior segment of left upper lobe.

Case 9.5

HISTORY: Dysphagia in a 30-year-old man

FINDINGS: Axial CT images (Figs. 9.5.1 and 9.5.2) show a large, sharply marginated, fluid density subcarinal mass (arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Bronchopulmonary-foregut cyst

DISCUSSION: A bronchopulmonary-foregut cyst is a developmental anomaly that is lined by columnar epithelium, and is filled with either clear serous or thick mucoid material (9). The distinction between cyst of bronchial or foregut origin may not be evident until resection. Although most bronchopulmonary-foregut cysts are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered on routine chest radiographs, they may become infected, resulting in symptoms. Large bronchopulmonary-foregut cysts within the mediastinum can create symptoms related to compression of the trachea and esophagus, including dyspnea and dysphagia.

Bronchopulmonary-foregut cysts can occur anywhere in the mediastinum and are usually round or ovoid masses near the carina (9). Congenital cysts may be easier to categorize when there is only one evident site of origin, that is, bronchogenic cysts may be intrapulmonary, whereas foregut cysts may be found along the lower esophagus.

On CT images, bronchogenic cysts typically appear as homogeneous water-attenuation masses. When the fluid contains calcium oxalate, proteinacious material, or hemorrhage, the contents of the cysts may have higher attenuation and may mimic soft tissue masses (10). On T1-weighted MR images, the bronchogenic cyst may have low-signal intensity, or it may have high-signal intensity if the contents of the cysts are proteinacious. On T2-weighted images, the cyst has homogeneously high attenuation (10).

Bronchogenic cysts are often treated by surgical excision to relieve or avoid symptoms of compression or infection. An alternative to surgery is needle aspiration of the mediastinal cyst and may be done via a trans-esophageal approach (11).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Bronchopulmonary-foregut cysts are typically mediastinal and may be water attenuation or higher on CT.

The tissue of origin of a mediastinal cyst may be difficult to accurately predict when in the upper mediastinum or subcarinal recess.

Case 9.6

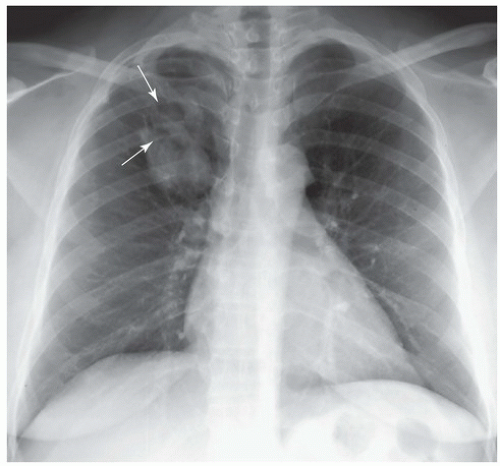

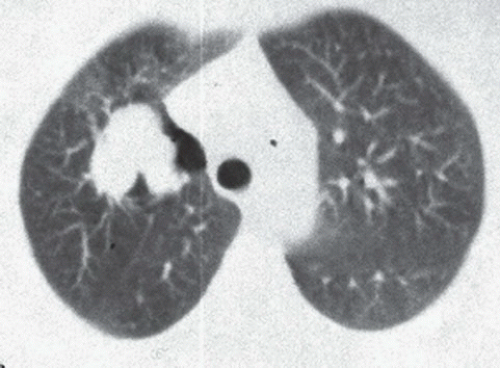

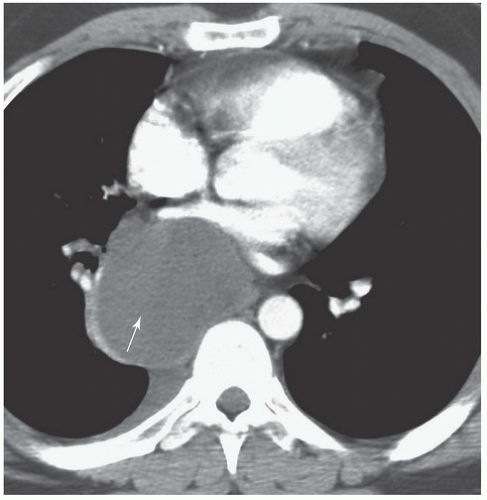

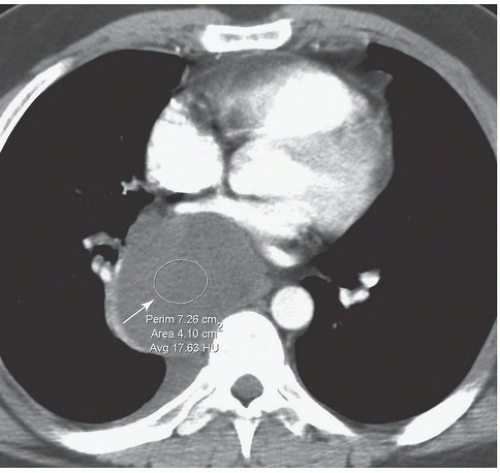

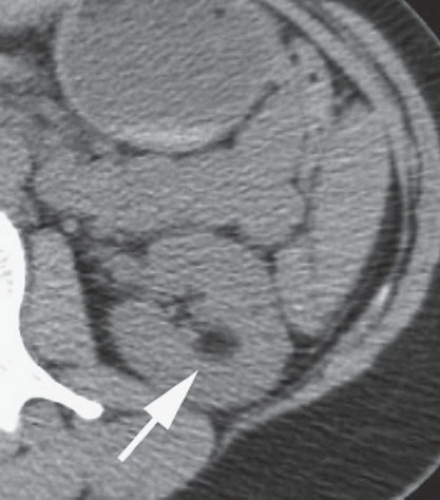

HISTORY: A 36-year-old female with recurrent pneumothoraces

FINDINGS: Frontal chest radiograph (Fig. 9.6.1) reveals overinflated lungs and subtle fine reticular opacities and cystic lucencies. HRCT through upper and mid lungs demonstrates numerous discrete round cystic spaces of varying sizes that have barely perceptible walls (Figs. 9.6.2 and 9.6.3). Non contrast image through the left kidney demonstrates fat containing lesion (Fig. 9.6.4, arrow).

DIAGNOSIS: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) with angiomyolipoma of the kidney

DISCUSSION: LAM is a rare, idiopathic disorder that almost exclusively affects women of childbearing age. Pathologic findings in LAM are characterized by diffuse interstitial proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the lungs. Patients typically present with dyspnea and recurrent pneumothoraces. The most commonly described radiographic manifestation of LAM is a pattern of generalized, symmetric, reticular, or reticulonodular opacities, seen in approximately 80% to 90% of affected patients (12). It is postulated that these reticular and reticulonodular opacities result from the visualization of numerous superimposed cyst walls. Lung volumes are normal to increased.

Typical CT and HRCT findings of LAM include diffuse bilateral thin-walled cysts surrounded by normal intervening lung parenchyma, affecting all zones equally. The cysts range from 2 to 5 mm in diameter but have been reported to be as large as 25 mm. Cystic changes of LAM are apparent on conventional chest CT; however, individual cysts, their extent, and distribution are better seen at HRCT (12). Other features of LAM include adenopathy, pleural effusions, and pneumothoraces.

Abdominal findings can be present in >70% of patients with LAM (13). The most common finding is renal angiomyolipoma that can occur in up to 50% of patients with LAM. Some investigators claim that isolated pulmonary LAM and LAM associated with renal angiomyolipomas are a forme fruste of tuberous sclerosis.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Diffuse bilateral thin-walled cysts throughout the lungs in women of childbearing age are diagnostic of LAM.

Extrathoracic related findings are present in >70% of cases.

Case 9.7

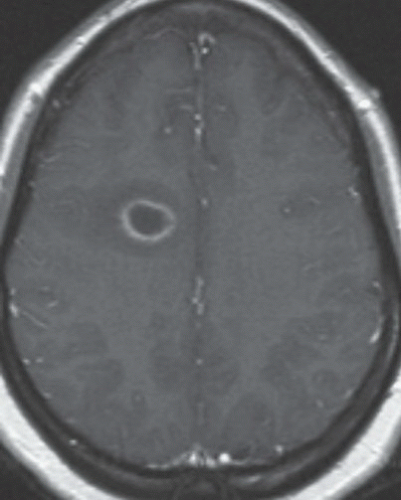

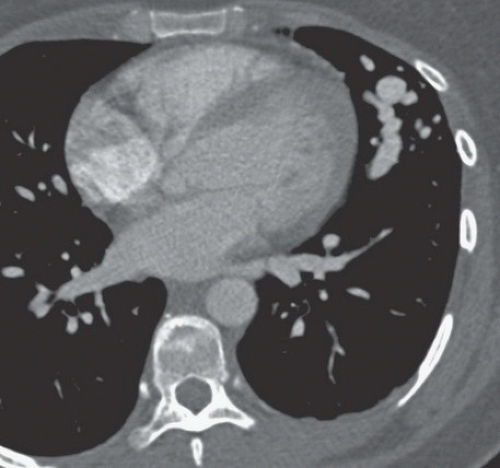

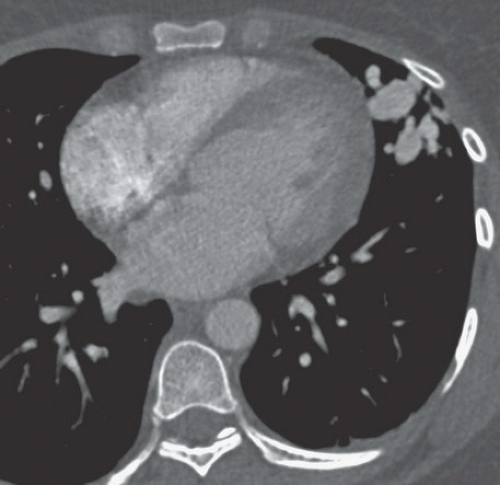

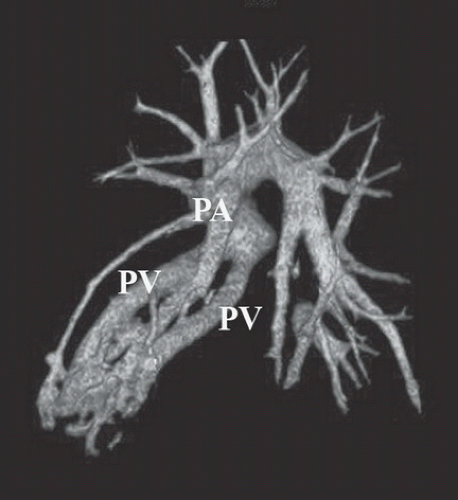

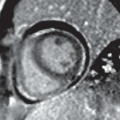

HISTORY: A 36-year-old woman with mental status changes

FINDINGS: Gadolinium-enhanced MR image reveals ring enhancing right parietal lesion (Fig. 9.7.1). Contrast-enhanced CT reveals a tangle of large enhancing vessels in the lingula (Figs. 9.7.2 and 9.7.3). Three-dimensional volume-rendered image (Fig. 9.7.4) shows the architecture to better advantage (PA = pulmonary artery; PV = draining pulmonary veins).

DIAGNOSIS: Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) with cerebral abscess

DISCUSSION: PAVMs are abnormal communications between pulmonary arteries and pulmonary veins. The majority of PAVM are congenital in origin. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, a popular hypothesis is incomplete resorption of vascular septae in the lungs (14). PAVM may also be acquired as a result of pulmonary right-to-left shunting in association with various conditions including hepatic cirrhosis, mitral stenosis, and trauma, among others. PAVMs can be divided into two types. Simple PAVM is a single large pulmonary artery to pulmonary vein communication, which is usually nonseptate. Complex PAVM has multiple feeding arteries and draining veins, usually with a septate aneurysmal communication between arteries and veins (15). Because the normal pulmonary capillary bed is bypassed, untreated arteriovenous malformations may cause dyspnea and cyanosis as a result of the pulmonary to systemic shunt and cerebrovascular ischemia and infarction, as well as brain abscess, as a result of the passing of emboli and bacteria directly into the systemic circulation (16,17). A cerebral event (stroke or abscess) as in this case may be the initial clinical manifestation of a PAVM.

Contrast-enhanced CT has been shown to be the standard in diagnosis of PAVM as well as treatment planning. The typical appearance is either blood vessels connected to a serpiginous mass or a homogenous, delimited mass of several centimeters in diameter. CT has been shown to be superior in sensitivity to pulmonary angiography, particularly with thin sections and multi-planar reformations through the absence of lesion superimposition on CT as well as detect other small PAVMs. Maximum intensity projection (MIP) images can be particularly helpful in displaying the entire AVM as well as its architecture (18). Pulmonary angiography, however, is still necessary to determine the full architecture of a PAVM, and for treatment with embolization.

Approximately 70% of cases with PAVM are associated with Osler-Weber-Rendu Syndrome, also known as Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, an autosomal dominant disorder associated with multiple organ arteriovenous malformations (14).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Approximately 70% of patients with a PAVM have hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Case 9.8

HISTORY: A 61-year-old woman with cough and dyspnea

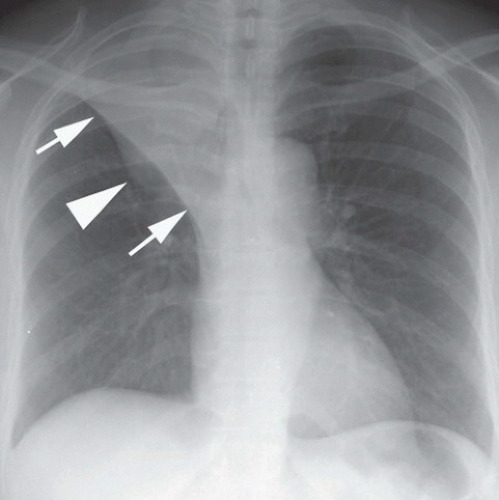

FINDINGS: On the frontal chest radiograph (Fig. 9.8.1), there is superior retraction of the right hilum and minor fissure (arrows), with mass causing a reverse-S configuration (arrowhead).

DIAGNOSIS: Right upper lobe collapse caused by primary lung neoplasm—“S sign of Golden”

DISCUSSION: In 1925, Golden described the orientation of the minor fissure in patients with upper lobe collapse caused by a central mass (19). The medial aspect of the minor fissure outlines the inferior margin of the mass; the lateral aspect of the minor fissure moves superiorly as the right upper lobe collapses, producing a reverse-S appearance. Additional signs of volume loss in the right upper lobe include rightward shift of the trachea and mediastinum, elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with a juxtaphrenic peak, with resulting hyperexpansion of the right middle and lower lobes, and crowding of the ribs (20,21).

Lobar collapse in an adult is often the result of an endobronchial lesion. In the outpatient setting, the primary consideration is a neoplasm until proven otherwise, whereas a mucus plug is a common cause of lobar collapse in the hospitalize patient. Collapse may also occur as a result of extrinsic compression of the bronchus or by a bronchial stricture. The appearance of the collapse can be a clue to the cause. A relatively straight margin can be seen with collapse owing to mucus plugging or other small endobronchial lesion, whereas larger lesions produce a focal convexity in the fissure as in this case.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

The S sign of Golden indicates right upper lobe collapse caused by central mass.

Case 9.9

HISTORY: A 57-year-old woman with a history of breast carcinoma

FINDINGS: Axial HRCT images of right lung (1-mm collimation, high spatial frequency algorithm, targeted image) show thickening of the interlobular septa throughout the right lung. Polygonal structures represent secondary pulmonary lobules outlined by thickened septa (Fig. 9.9.1, arrows). The bronchovascular bundles seen tangentially and in cross-section are thickened (Fig. 9.9.2, arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Lymphangitic carcinomatosis

DISCUSSION: Lymphangitic spread of tumor in the lung is a relatively rare metastatic pattern, typically to the result of adenocarcinomas. The tumor cells are deposited in the lung periphery by hematogenous dissemination and then, rather than forming the typical nodule, infiltrate the pulmonary lymphatics and interlobular septa growing back toward the hila, producing thickening of the interlobular septa and peribronchovascular interstitium (22). Occasionally, the spread of lymphoma can also occur along pulmonary lymphatics, extending peripherally from a central lesion. Although pulmonary sarcoidosis may mimic this radiographic appearance, the patient’s clinical presentation and past medical history should allow for confident distinction of the two. In particular, the presence of unilateral disease or pleural effusion strongly favors lymphangitic carcinoma (23). When in doubt the diagnosis can be confirmed by bronchoscopy with trans-bronchial biopsy. It is important to remember that lung cancer and treatment of lung cancer with radiation therapy may lead to central venous and lymphatic obstruction that may result in interstitial opacities (24). This local phenomenon should not be confused with lymphangitic carcinomatosis and the inappropriate use of this term can have grave implications with the misclassification of staging leading to inappropriate therapy.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Lymphangitic carcinomatosis refers to hematogenous dissemination of tumor with growth toward the hila along the pulmonary interstitium.

Case 9.10

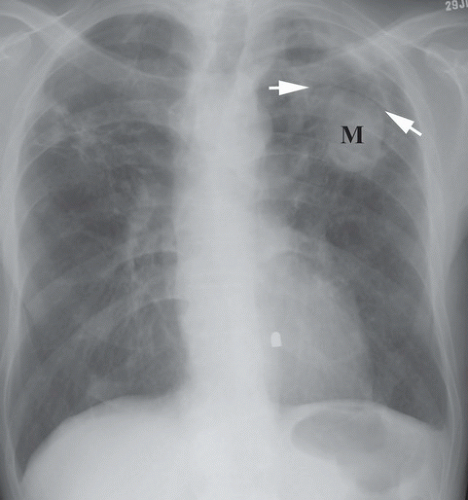

HISTORY: A 35-year-old woman with cough

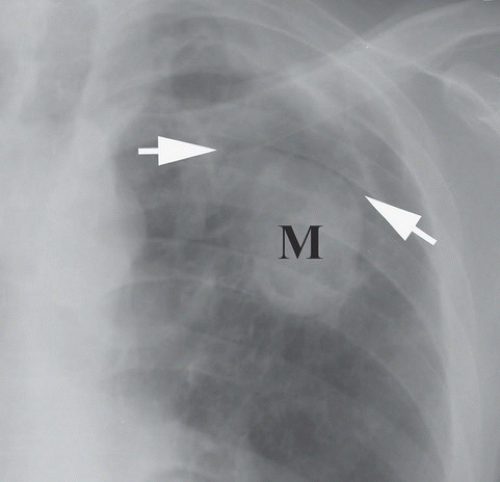

FINDINGS: A frontal chest radiograph (Fig. 9.10.1) reveals fibrocavitary changes in the upper lobes with a dependent soft-tissue mass in the left upper lobe cavity. A detail of the left upper lobe reveals a rounded mass (M) with well-defined superior border and thin rim of surrounding gas (Fig. 9.10.2, arrows).

DIAGNOSIS: Aspergilloma

DISCUSSION: Aspergillomas occur as a result of colonization of a preexisting cavitary lesion that may be produced by tuberculosis, fibrocavitary sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis, emphysema, or bronchiectasis (16). Pleural thickening adjacent to the cavity may precede visualization of the fungus ball, especially true in fibrocavitary sarcoidosis (17). In cavities resulting from tuberculosis, the incidence of aspergilloma may be as high as 10% (25). The aspergilloma itself consists of a mass of hyphae mixed together with mucus and cellular debris and as such represent a saprophytic form of infection. Although typically found in the upper lobes, aspergillomas can occur anywhere a cavity exists.

Although mild hemoptysis occurs within the majority of affected individuals, bleeding can be severe and life-threatening massive hemoptysis may require embolization (25). This is typically because of erosion into a bronchial artery, in particular with massive hemoptysis, but may also occur as a result of erosion into a pulmonary artery.

Treatment of aspergilloma is limited owing to the lack of blood supply. In most cases, no specific therapy is warranted and treatment is aimed at complications (such as bronchial artery embolization). In selected cases intracavitary instillation of amphotericin has been performed with variable results. In rare cases, surgery is necessary for control of recurrent hemoptysis and is associated with a relatively high rate of morbidity and mortality (25).

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

The saprophytic form of Aspergillus infection is recognized as a fungus ball (aspergilloma) within a preexisting cavity.

Common causes of the preexisting cavity include tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and emphysema.

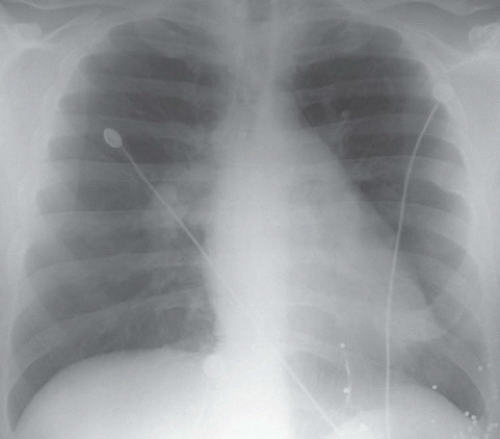

Case 9.11

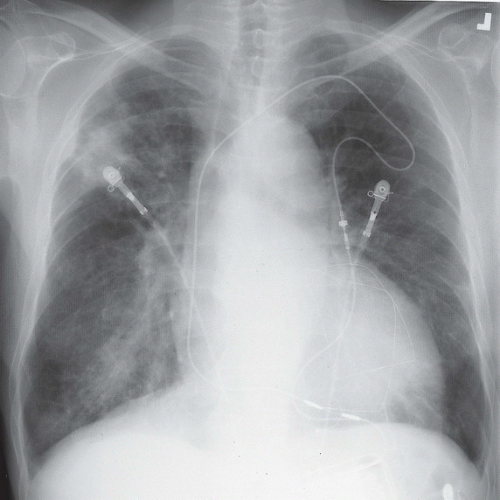

HISTORY: A 72-year-old man with a history of recurrent ventricular tachycardia, now with exertional dyspnea and nonproductive cough

FINDINGS: Chest radiograph (Fig. 9.11.1) shows cardiomegaly and a transvenous pacemaker as well as automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) patches. Focal areas of increased opacity in the right upper lobe are better seen on the CT images (Figs. 9.11.2 and 9.11.3) as areas of high attenuation (almost as high as the contrast-enhanced aorta).

DIAGNOSIS: Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity

DISCUSSION: Amiodarone is an anti-arrhythmic agent that can cause pulmonary toxicity in 1% to 15% of treated individuals (26). Pulmonary toxicity may manifest within days of starting the medication and most cases will develop within 1 to 1.5 years

after initiation of therapy. Toxicity appears to be dose-dependent with pulmonary symptoms manifesting more rapidly at higher doses and amiodarone pneumonitis is less likely to occur with dosages of ≤400 mg/day (26). Most often, patients present with a subacute course of dyspnea and nonproductive cough, but a more acute onset that mimics pulmonary infection can also be seen.

after initiation of therapy. Toxicity appears to be dose-dependent with pulmonary symptoms manifesting more rapidly at higher doses and amiodarone pneumonitis is less likely to occur with dosages of ≤400 mg/day (26). Most often, patients present with a subacute course of dyspnea and nonproductive cough, but a more acute onset that mimics pulmonary infection can also be seen.

Chest radiographs may show focal areas of interstitial disease or dense areas of alveolar consolidation that are often asymmetric. The CT appearance may be quite varied with interstitial, alveolar, and mixed patterns of disease. Most often the presentation is similar to that of nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis or cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, whereas fibrosis (UIP pattern) and diffuse alveolar damage are rare (27). High attenuation alveolar consolidation is thought to be related to the high iodine content (37% by weight) of amiodarone and its prolonged half-life within the lung and is considered to be pathognomonic in the appropriate clinical setting (28). Unfortunately, high-attenuation pulmonary opacities are a relatively uncommon manifestation of disease. Attenuation of the liver and spleen is also often increased from iodine accumulation and is a marker of amiodarone use rather than toxicity. This feature, however, can be helpful when nonspecific pulmonary opacities are present and raise the possibility of amiodarone pulmonary toxicity.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearl

Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity is dose-related and may produce high-attenuation lung consolidation on CT.

Case 9.12

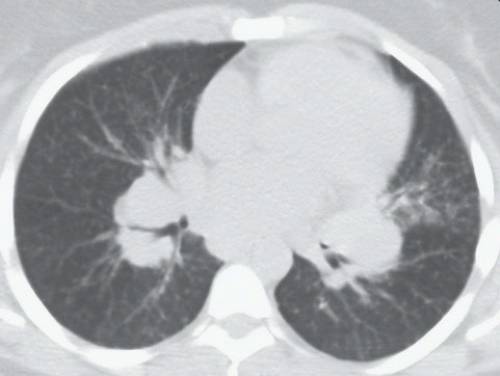

HISTORY: A 28-year-old asymptomatic man, routine chest radiograph

FINDINGS: Bilateral hilar (R and L), right paratracheal, aortopulmonary window, and subcarinal (S) lymphadenopathy are present on PA and lateral views of the chest with faint reticulonodular opacities in both lungs (Figs. 9.12.1 and 9.12.2). Axial CT (Fig. 9.12.3) confirm the adenopathy as well as reveal small subpleural, peribronchovascular, and perilymphatic nodules.

DIAGNOSIS: Sarcoidosis

DISCUSSION: Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown etiology characterized by formation of noncaseating epithelioid granulomata within lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and other organs (29).

The clinical and radiological manifestations of sarcoidosis are predominantly related to pulmonary

involvement, and pulmonary involvement is present in approximately 90%. The most common radiographic finding in sarcoidosis is bilateral hilar, subcarinal, and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy (30). The chest x-ray may be normal in up to 10% even with nodal or lung parenchyma involvement. CT often reveals enlarged lymph nodes within the aortopulmonary window and the left paratracheal region as well. The interstitial pattern is often reticulonodular with small nodules located along bronchovascular bundles (29). Pulmonary parenchymal involvement in fact can be quite varied with patterns ranging from miliary nodules, to air-space opacities, to end-stage fibrosis and cavitation. With chronic pulmonary disease, fibrosis and bullae may predominate, typically with an upper lobe distribution.

involvement, and pulmonary involvement is present in approximately 90%. The most common radiographic finding in sarcoidosis is bilateral hilar, subcarinal, and right paratracheal lymphadenopathy (30). The chest x-ray may be normal in up to 10% even with nodal or lung parenchyma involvement. CT often reveals enlarged lymph nodes within the aortopulmonary window and the left paratracheal region as well. The interstitial pattern is often reticulonodular with small nodules located along bronchovascular bundles (29). Pulmonary parenchymal involvement in fact can be quite varied with patterns ranging from miliary nodules, to air-space opacities, to end-stage fibrosis and cavitation. With chronic pulmonary disease, fibrosis and bullae may predominate, typically with an upper lobe distribution.

Sarcoidosis can be staged by chest radiographs as stage 0 (no chest radiographic involvement), stage I (disease limited to mediastinal nodes), stage II (lung parenchyma and lymph node involvement), stage III (lung parenchyma involvement only), and stage IV (end-stage pulmonary fibrosis). In most cases the initial disease presentation regresses (with or without treatment), but when clinical progression of sarcoidosis occurs it often follows this radiographic continuum.

Aunt Minnie’s Pearls

Classic HRCT findings include well-defined nodules along the interlobular septa, peribronchovascular bundles, and pleural surfaces and smooth or nodular peribronchovascular thickening.

Subpleural and peri-fissural nodules are important in distinguishing sarcoidosis from the centrilobular nodules of hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Case 9.13

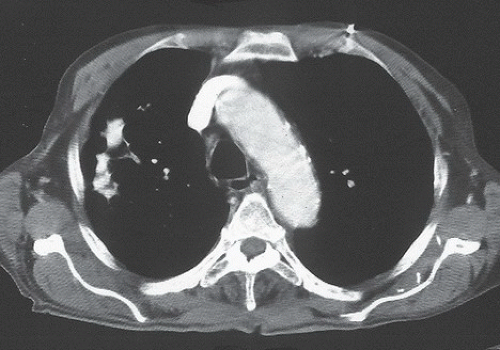

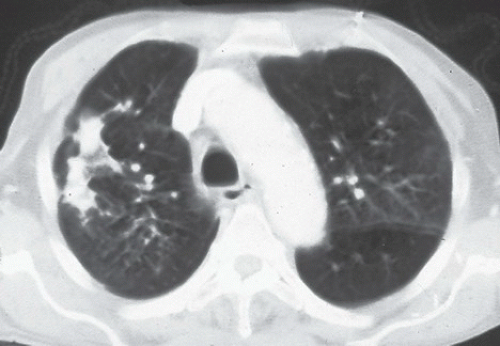

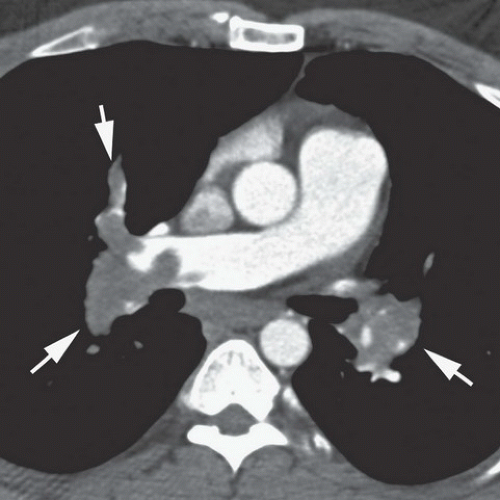

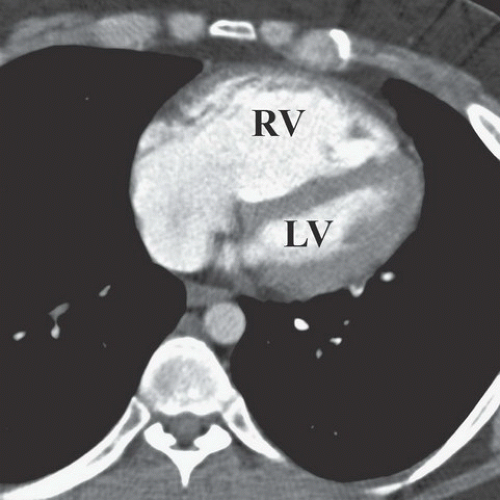

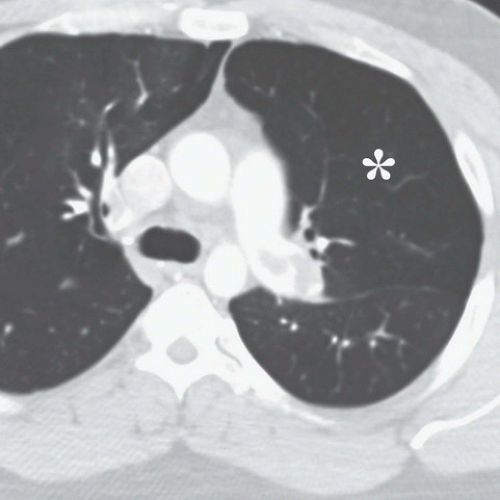

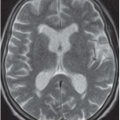

HISTORY: A 34-year-old male with acute dyspnea and pleuritic chest pain 3 days after suffering major lower extremity trauma

FINDINGS: On the chest radiograph (Fig. 9.13.1), the central pulmonary arteries are enlarged and there is upper lobe oligemia. On a contrast-enhanced CT image, there is extensive clot in both the right and left pulmonary arterial system (Fig. 9.13.2, arrows). In addition, there is relative enlargement of the right ventricle (RV) compared with the left (LV) and shift of the interventricular septum to the left, a finding of right heart strain (Fig. 9.13.3). The left upper lobe oligemia can be better appreciated with lung windows (Fig. 9.13.4, asterisk).

DIAGNOSIS: Acute pulmonary embolism (PE)

DISCUSSION: Acute PE is a relatively common event with a wide spectrum of clinical presentation that ranges from small asymptomatic and incidentally detected subsegmental PE to life-threatening central PE causing hypotension, myocardial infarction, and cardiogenic shock. The overall incidence has been estimated at approximately 1 per 1,000 population in the United States (31). Pulmonary emboli are most often the result of thrombi dislodged from the deep veins of the legs. Risk factors for PE include advanced age, malignant disease, pelvic or abdominal surgery, orthopedic surgery in the lower limbs, prolonged immobilization, obesity, congestive heart failure, and trauma. Dyspnea and chest pain, often pleuritic in nature, are the only symptoms reported by >50% of patients with PE.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree