Ultrasound of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Patients are commonly referred for US examination of the abdomen because of vague and non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain or abdominal distention. The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a common site of disease in these patients [1]. Rather than being “between the transducer and what we want to see,” the GI tract is what we want to see. Nonetheless, examination of the GI tract by US is challenging because of obscuring bowel gas and confusing artifacts.

Imaging Technique

In the setting of acute abdominal pain, US examination should include the GI tract as well as the solid organs of the abdominal cavity. In women, transvaginal US should be added if transabdominal US is not conclusive. Graded compression US is utilized to examine the intestinal tract [2]. The patient is asked to localize the area of maximal pain or tenderness and attention is focused on that area. A linear array 7-to 10-MHz transducer is utilized. In large patients a 5-MHz linear or curved array transducer may be needed. Color Doppler US greatly aids in the detection of inflammation.

Anatomy

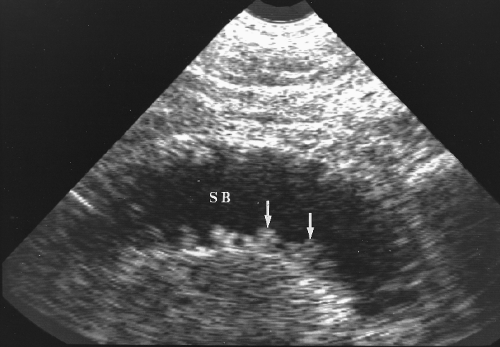

The GI tract has a recognizable “gut signature” that identifies bowel during US examination. Although the wall of the intestinal tract has 5 histologic layers, a 3-layer pattern is usually demonstrated by US (Fig. 4.1). The innermost mucosa and submucosa are seen as a distinct echogenic rind that surrounds the gut lumen. The inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of the muscularis propria produce a central hypoechoic muscle layer on US. The outer adventitia/serosa and surrounding fat produce an outer echogenic layer. Thus the usual gut signature shown by US is two echogenic layers separated by a hypoechoic muscle layer that define the wall of the GI tract. The lumen of the gut may contain fluid, food, stool, and air in varying combinations at different locations. Portions of the GI tract are identified by location, appearance, peristaltic activity, and luminal contents.

The stomach is a large sac in the left upper quadrant and epigastrium. It commonly contains fluid and air and, if the patient has recently eaten, food. The antrum extends across the pancreas to the duodenum. The duodenal bulb is commonly just inferior to the gallbladder. The third portion of the duodenum is the only portion of the GI tract that extends posterior to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and vein (SMV). The jejunum and ileum occupy the central abdomen. The jejunum is identified by its regular folds, the valvulae conniventes, that produce a “keyboard” pattern seen when fluid is in the lumen (Fig. 4.2). The ileum lacks folds and has a flat featureless wall pattern.

The normal appendix is a narrow tube approximately 10 cm in length (Fig. 4.3). It arises from the tip of the cecum approximately 3 cm below the ileocecal valve. The base of the appendix has a constant relationship to the tip of the cecum, but the remainder of the appendix is free and variably located. It may be behind or below the cecum, behind or in front of the distal ileum, in the pelvis, or occasionally in the left side of the abdomen. The great variability in location influences the clinical presentation of acute appendicitis.

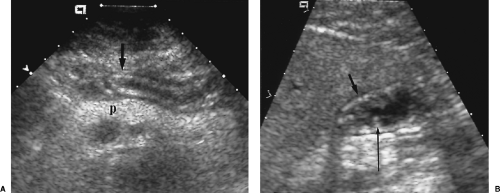

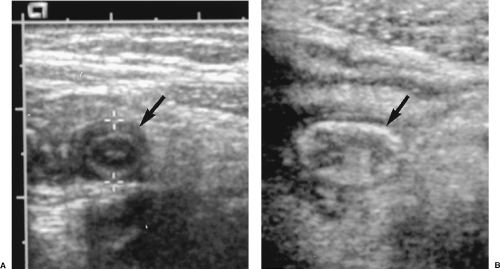

Figure 4.3 Normal Appendix. A normal appendix (longer arrow) is shown in long axis (A) and short axis (B). This patient has an iliac artery graft (shorter arrow). |

Figure 4.4 Ileum versus Appendix. A. In transverse section, the appendix (arrow, between cursors, +) is round and smaller. B. In transverse section, the distal ileum (arrow) is oval and larger. |

In short axis section the appendix is round, whereas the ileum and colon are oval or elliptical (Fig. 4.4). The colon is identified by its larger size, haustral pattern, and stool content. Stool is heterogeneous in echotexture and liquid, semi-solid, or solid in consistency. Stool commonly contains tiny gas bubbles that produce bright echoes at varying depths.

Wall Thickening

The normal bowel wall is 2-5 mm in thickness depending upon distention (Fig. 4.1). Wall thickening is nearly always pathologic but is often a non-specific finding. More precise diagnosis is made by detailed examination and correlation with clinical findings [5]. Benign wall thickening produces a target or bull’s-eye appearance and is usually uniform and symmetric (Figs. 4.5, 4.6). Any wall thickening, focal or diffuse, that exceeds 25 mm in thickness is more likely to be malignant. Masses demonstrate focal, asymmetric wall thickening, and may extend intraluminally or be exophytic (Fig. 4.7). Differential diagnosis of thickening of the wall of the small bowel and colon is listed in Boxes 4.1 and 4.2 [5].

Crohn’s Disease

US can demonstrate characteristic features of Crohn’s disease [5].

Circumferential thickening of the wall of affected bowel >5 mm is indicative of the presence of disease.

Strictures show marked thickening of the bowel wall with fixed narrowing of the lumen. Dilatation of proximal bowel and hyperperistalsis may be evident [6].

Mesenteric lymphadenopathy appears as multiple oval hypoechoic masses.

Skip areas of normal bowel are seen between affected segments.

The distal ileum is nearly always involved.

Increased blood flow may be demonstrated in areas of wall thickening, reflecting active inflammation [4].

Figure 4.5 Benign Gastric Wall Thickening. The wall of the gastric antrum (arrow) as seen in short axis view is diffusely and symmetrically thickened by adjacent acute pancreatitis. |

Lymphoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract

The GI tract is the most common site of extra-nodal involvement by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Most commonly involved sites are the stomach, small bowel, cecum, and remainder of the colon.

Profound circumferential thickening of the wall is characteristic. Thickening up to 4 cm is common.

Thickening may be nodular and asymmetric.

Enlarged mesenteric and retroperitoneal nodes are common.

Peristalsis is characteristically preserved with a notable lack of bowel obstruction despite marked involvement.

Box 4.1: Causes of Wall Thickening of the Small Bowel

| Wall edema | Malignancy |

| Postoperative | Lymphoma |

| Cirrhosis/ascites | Peritoneal carcinomatosis |

| Hypoproteinemia | Mesenteric ischemia/infarction |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Thrombosis of mesenteric veins |

| Crohn’s disease | Thrombosis of mesenteric arteries |

| Acute ileitis (Yersinia Campylobacter) | Small bowel disease/malabsorption |

| Extraintestinal inflammatory conditions | Celiac disease |

| Pancreatitis | Whipple’s disease |

| Endometriosis | Benign intestinal tumors (adenoma, lipoma) |

| Adapted from Ledermann HP, Börner N, Strunk H, et al. Bowel wall thickening on transabdominal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:107–117. | |

Colitis

Pseudomembranous (Clostridium difficile) colitis has become increasingly common in the hospital setting, causing antibiotic therapy-related diarrhea [7]. Ischemic colitis and other forms of infectious and noninfectious colitis have similar findings [8].

Gross edema of the submucosa is reflected in marked thickening and decreased echogenicity of the inner hyperechoic layer of the colon.

The swollen submucosa may be folded into a gyral pattern.

Intraluminal gas is strikingly absent.

Most patients (64-77%) have accompanying ascites.

Acute Diverticulitis

Acute diverticulitis of the colon is a common cause of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Most present with left lower quadrant pain, fever, and leukocytosis [9,10].

The involved segment of colon shows concentric hypoechoic thickening, predominantly involving the muscle layer.

Inflamed diverticuli commonly contain impacted fecaliths or gas and appear as bright echogenic foci with ring-down artifact adjacent to the thickened bowel.

Pericolonic inflammation produces poorly defined hypoechoic areas adjacent to the involved bowel.

Pericolonic abscesses are seen as loculated fluid collections containing anechoic or echogenic fluid and, sometimes, gas.

Echogenic or hypoechoic linear tracts in the colon wall or extending to bladder, vagina, or other bowel suggests fistulae and sinus tracts.

Thickening and inflammation of the colonic mesentery are sometimes evident.

Box 4.2: Causes of Wall Thickening of the Colon

| Inflammation | Malignancy |

| Diverticulitis | Colon carcinoma |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Lymphoma |

| Crohn’s disease | Peritoneal carcinomatosis |

| Ulcerative colitis | Edema |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | Postoperative |

| Appendicitis | Cirrhosis/ascites |

| Extracolonic inflammatory conditions | Hypoproteinemia |

| Endometriosis | Ischemia/infarction |

| Ischemic colitis | |

| Colon infarction | |

| Adapted from Ledermann HP, Börner N, Strunk H, et al. Bowel wall thickening on transabdominal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000;174:107–117. | |

Colon Carcinoma

Although US is not the method of choice for colon cancer detection, tumors may be identified unexpectedly in patients presenting with acute or chronic symptoms [11].

Colon cancer may present as a bulky mass up to 10 cm or more in size. On US the mass is usually hypoechoic with irregular, lobulated, or ill-defined contours (Fig. 4.8).

Intraluminal gas is commonly seen eccentrically located around the tumor.

Segmental, circumferential, or eccentric thickening of the colon wall may also represent colon cancer (Fig. 4.9).

Colonic obstruction may be evident with colon and small bowel dilatation.

Bowel Obstruction

US may provide evidence of the presence and cause of bowel obstruction [12]. US is particularly good at demonstrating fluid-filled, dilated bowel loops when the abdomen is gasless and difficult to evaluate on plain film radiography. Gas-filled bowel loops seriously impair US assessment. US evaluation of adynamic ileus is limited because large amounts of gas are usually present in the bowel lumen.

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

The differential diagnosis of vomiting in the first two months of infancy includes hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS), pylorospasm, malrotation with Ladd’s bands or midgut volvulus, duodenal atresia, and gastroesophageal reflux. Barium studies are preferred in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux and confirmation of malrotation. US is the examination of choice for HPS [13].

The US examination is performed with fluid in the stomach and the infant in right posterior oblique position. This position places fluid in the antropyloric region for optimal visualization. The infant can be fed glucose solution if the stomach is empty. However, excessive feeding must be avoided because overdistention of the stomach displaces the pylorus posteriorly and makes examination more difficult [14]. Imaging is performed in the epigastrium along the edge of the liver. The fluid-filled antrum is tracked to the pylorus. The pylorus is carefully evaluated in transverse and longitudinal section for documentation of muscle thickness and length of the pyloric channel, and observation for peristalsis and fluid movement through the pylorus.

Normal Pylorus

The normal pylorus is significantly more difficult to identify than the abnormally thickened pylorus (Fig. 4.10).

Muscle thickness <2 mm in transverse plane is unequivocally normal. The circular muscle may be so thin that it is difficult to measure.

The length of the pyloric channel is short, often <10 mm. It may be so short that it, too, is difficult to measure.

Peristaltic activity is observed to pass through the antrum and open the pylorus, allowing passage of fluid through the pylorus into the duodenum.

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophy of the circular muscle of the pylorus constricts the pyloric channel, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction and projectile nonbilious vomiting. HPS most often affects infants 2-6 weeks old. Rarely, the condition presents at birth or as late as 5 months of age. Boys are affected five times more frequently than girls. In the United States, HPS is usually treated surgically with longitudinal pyloromyotomy.

The pyloric muscle is thickened and the pyloric channel is elongated (Fig. 4.11).

On short axis images, the abnormal pylorus resembles a bull’s eye with hypoechoic thickened muscle surrounding central echogenic submucosa.

Muscle thickness >3 mm is diagnostic of HPS [14]. Muscle thickness is measured from the echogenic submucosa to the outer edge of the hypoechoic muscle band [15]. Care

must be taken to make measurement in true transverse plane to the pylorus. Oblique planes falsely increase the apparent muscle thickness [14].

Length of the pyloric channel greater than 12 mm is indicative of HPS. Pyloric channel length is measured along the persistently contracted portion of the pylorus [15].

No peristalsis or passage of fluid through the pylorus is observed. Gastric peristalsis through the antrum ends abruptly at the pylorus.

A “shoulder sign” may be seen as the bulging impression of hypertrophied muscle on the wall of the gastric antrum.

The “antral nipple sign” describes the prolapse of folded pyloric mucosa into the fluid-filled antrum [16]. A “tit” sign is produced by fluid extending into the contracted pylorus (Fig. 4.11B).

Anisotropic effect causes increased echogenicity of the muscle band in transverse section at 6 and 12 o’clock positions. This artifact creates difficulty in muscle measurement [14,17].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree