Abstract

Peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) are benign, multilocular fluid-filled lesions that predominantly affect women of reproductive age, often arising after abdominal surgery or chronic inflammation. We present the case of a 30-year-old woman with a history of laparotomy for a myometrial mass, who developed severe lower abdominal pain and distension 5 months postsurgery. Initial ultrasound revealed a large intraperitoneal fluid collection measuring 10 cm, with debris and septations. MRI further characterized the lesion as a peritoneal inclusion cyst, showing enhancing septations and no solid components. The patient underwent laparotomy for adhesion release and complete cyst excision, leading to complete symptom resolution. At 6-month follow-up, she remained asymptomatic with no evidence of recurrence. This case underscores the importance of considering PICs in the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain or cystic lesions in women with a history of abdominal surgery. Imaging, particularly ultrasound and MRI, plays a critical role in diagnosing PICs and distinguishing them from other conditions such as paraovarian cysts, hydrosalpinx, or ovarian malignancies. Treatment options range from conservative management to surgical intervention, depending on the patient’s symptoms and clinical presentation. Early recognition and appropriate management of PICs can prevent complications and improve outcomes. This report highlights the diagnostic challenges and therapeutic approaches for PICs, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach in managing these lesions.

Introduction

Peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) are benign and reactive lesions typically found in women of reproductive age, often following abdominal surgery or in cases of chronic inflammation [ ]. These cysts, which manifest as multilocular fluid-filled formations, are located within the abdominopelvic cavity and may sometimes be incidentally discovered in asymptomatic patients during imaging studies [ ].

Case presentation

A 30-year-old woman with a 5-year history of infertility presented with progressively worsening lower abdominal pain and distension over 3 months. Initially, the pain was intermittent but progressively became constant and severe, accompanied by bloating and mild nausea. Eight months earlier, she had undergone a laparotomy for a myometrial mass, which was diagnosed histologically as a smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential (STUMP). The prior surgery had been uncomplicated, with no postoperative issues. Her family history was unremarkable for malignancy or gynecological disorders, and there were no known hereditary conditions such as Lynch syndrome or BRCA mutations.

On examination, the patient appeared uncomfortable due to abdominal distension but was hemodynamically stable. Abdominal palpation revealed diffuse tenderness without rebound tenderness or guarding. There was no palpable mass or signs of peritonitis, and bowel sounds were present and normal.

Laboratory investigations, including a normal complete blood count (WBC: 8.5 × 10³/µL), normal inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein: 5 mg/L; ESR: 15 mm/hr), and normal liver, renal function, and tumor markers (CA-125: 18 U/mL; CEA: 2.5 ng/mL), were all unremarkable. A pregnancy test was negative.

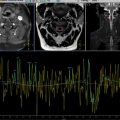

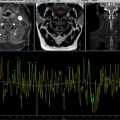

Abdominopelvic ultrasound revealed a complex intraperitoneal fluid collection with multiple septations and internal debris, raising suspicion for a peritoneal inclusion cyst. MRI confirmed a large, well-defined cystic lesion in the inter-uterorectal space, measuring 14 × 8 cm, exhibiting T2 hyperintensity and T1 hypointensity, with thin septa and no solid components, consistent with a peritoneal inclusion cyst.

Given the patient’s increasing discomfort, the lesion’s size, and the potential risk of complications such as torsion or rupture, surgical intervention was pursued. Laparotomy revealed dense intra-abdominal adhesions surrounding a large, thin-walled cystic structure, containing clear, serous fluid and no signs of malignancy. The cyst was carefully dissected from surrounding adhesions, and complete excision was performed, along with extensive adhesiolysis to restore normal peritoneal anatomy.

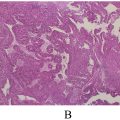

Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a peritoneal inclusion cyst, with a fibrous wall lined by mesothelial cells, and no atypia or neoplastic changes. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on postoperative day 4. At a 6-month follow-up, she reported complete resolution of symptoms, and imaging showed no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

Peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) develop in women of reproductive age, often following disruptions to the integrity of the peritoneum due to surgical interventions, trauma, inflammation, or endometriosis. These disruptions lead to a decreased ability of the peritoneum to absorb ovarian fluid, which is then trapped by postsurgical adhesions [ ]. This results in complex cystic masses composed of serous, gelatinous, or hemorrhagic fluid, without true cyst walls. The ovarian origin of this fluid is supported by studies showing higher concentrations of ovarian hormones in the peritoneal fluid compared to plasma [ ]. Although the exact nature of these cysts and their pathological process are not fully understood, the presence of functionally active ovaries and adhesions is essential for their development, which is consistent with their appearance after the onset of puberty [ , ].

Patients with peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) most commonly present with lower abdominal or pelvic pain, which can range from acute to chronic in nature. Additional symptoms may include abdominal distension, dyspareunia, constipation or a palpable mass [ , ]. Many have a history of pelvic surgery or intraperitoneal inflammation, such as endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease [ , ]. The duration of symptoms can vary widely, lasting from days to months, and the interval between previous surgery and detection of the PIC can range from 6 months to 20 years. Diagnosis can be challenging due to nonspecific symptoms, and PICs may be incidentally discovered during surgical procedures [ ]. Physical examinations may reveal no palpable masses, complicating the diagnosis further, as the clinical presentation can mimic other conditions like infected paraovarian cysts or endometriomas [ ].

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality for assessing pelvic pain due to its accessibility, low cost, and lack of radiation exposure. It is particularly effective in identifying peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs), which typically present as a normal ovary surrounded by anechoic fluid that may contain multiple septations. In some cases, this fluid can become echogenic if hemorrhagic or proteinaceous material is present. The trapped ovary in such scenarios often takes on the appearance of a “spider in a web,” where adhesions create a complex cystic mass around it [ , ]. CT imaging provides additional insights, showing PICs as cystic masses with regular or irregular borders. These masses demonstrate attenuation properties indicative of fluid and/or hemorrhage, which helps in differentiating benign from malignant processes [ ]. MRI serves as a valuable second-line imaging technique, especially for more complex cases. It offers high soft-tissue resolution and multidimensional imaging capabilities, allowing for detailed characterization of pelvic masses. On MRI, PICs typically exhibit low T1 signals and high T2 signals consistent with serous fluid. When complicated by hemorrhage, they may show elevated T1 signals. The irregular shapes of PICs can be attributed to mass effects from adjacent structures, as these pseudocysts lack true walls. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images often reveal little to no enhancement of PICs, and the “spider in a web” appearance is a distinctive feature on MRI [ ]. This imaging modality also helps clarify the extraovarian nature of fluid collections, as the ovary may not be easily defined on ultrasound. Overall, the combination of ultrasound, CT, and MRI provides a comprehensive approach to diagnosing and managing PICs and other pelvic conditions.

The differential diagnosis for peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) involves several conditions that can complicate accurate identification. Key contenders include paraovarian cysts, hydrosalpinx or pyosalpinx, macrocystic lymphatic malformations, and ovarian epithelial malignancies. Other differential considerations include lymphoceles, mesenteric or omental cysts, pseudomyxoma peritonei, and malignant mesothelioma, which generally exhibit distinct features on imaging and clinical presentation [ , , ]. Accurate diagnosis often relies on imaging techniques such as ultrasound and MRI, alongside clinical history.

Treatment options for peritoneal inclusion cysts (PICs) encompass both conservative and surgical approaches, tailored to the patient’s symptoms and preferences. Conservative management includes observation, hormonal therapy with oral contraceptives to reduce ovarian fluid production, and pain management with medications [ ]. Image-guided interventions such as percutaneous or transvaginal aspiration, sclerotherapy, and potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser ablation are minimally invasive alternatives.[ , , ] Surgical options, including laparoscopic or open resection of cysts and adhesions, are considered for persistent symptoms, infertility, or severe cases. While surgery is often preferred for definitive management, it carries a recurrence rate of 30%-50% [ , , ]. Overall, treatment strategies are individualized based on cyst size, symptom severity, and patient circumstances.

Conclusion

Peritoneal inclusion cysts should be included in the differential diagnosis for abdominal pain, multilocular cystic lesions, or ascites in women with a history of abdominal surgery. Imaging is essential for diagnosing, monitoring, and managing these benign lesions with minimally invasive methods. While definitive diagnosis relies on histological examination, the unclear etiology and pathogenesis of peritoneal inclusion cysts prevent the establishment of a single, optimal treatment approach ( Figs. 1 and 2 ).