Fig. 14.1

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis, gross and histologic appearance. In situ photographs (a, b) in a patient with interstitial edematous pancreatitis showing an irregular area of hemorrhage infiltrating the peripancreatic tissues and extending into the mesentery of the small bowel (arrows). Note the tissue retraction due to bands of fibrous tissue. Microphotograph (c) (H&E, 50×) shows acini (arrow) adjacent to an edematous stroma with scattered neutrophils and few plasma cells (left right–up arrow)

Acute inflammation of the pancreatic parenchyma and peripancreatic tissues

Necrotizing pancreatitis (NP), (15 %) (Fig. 14.3)

Fig. 14.3

Necrotizing pancreatitis, gross and histologic appearance. In situ photograph (a) and surgical specimen (b) show amorphous necrotic pancreatic and adipose tissue secondary to enzymatic autolysis (a) (arrows). Microphotograph (c) demonstrates necrotizing pancreatitis surrounded by hemorrhage, acute and chronic inflammation, and early fibrosis. Note the complete destruction of a pancreatic lobule (long arrow). The adjacent pancreatic lobule retains normal architecture (short arrow) (H&E, 10×)

Inflammation associated with pancreatic parenchymal necrosis and peripancreatic necrosis

Sterile or infected

14.3 Pathophysiology

First phase: premature activation of trypsin within pancreatic acinar cells

Second phase: intrapancreatic inflammation through a variety of mechanisms and pathways

14.4 Histopathology

Fig. 14.2

Acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis, histology. (a) Acute hemorrhagic pancreatitis with areas of parenchymal (asterisk) and fat necrosis (arrowheads). The inset highlights the red blood cell infiltrate surrounding an islet of Langerhans cells and multiple viable and necrotic acini (H&E, 10×, 20×). (b) The inflammatory infiltrate is composed of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and red blood cells (circle). Neutrophils are also present in the lumen and the epithelium of the ducts (arrows). The stroma surrounding the ducts demonstrates mild edema (H&E, 50×)

Necrotizing vasculitis with occlusion and thrombosis of small feeding arteries and draining veins

Perilobular and/or panlobular fat necrosis affecting the acinar cells, islet cells, pancreatic ductal system, interstitial fatty tissue, areas of hemorrhage, and devitalized pancreatic parenchyma

14.5 Etiology of Acute Pancreatitis

Most common (80 %)

Gallstones

Alcohol

Other causes (20 %)

Smoking tabacco

Cannabis

Hypertriglyceridemia

Hypercalcemia

Trauma

Post ERCP (Post Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangio-pancreatography

Genetic mutations (hereditary pancreatitis)

Idiopathic

Pregnancy

Pancreatic divisum

Pancreatic neoplasms (adenocarcinoma, IPMN, or neuroendocrine)

Drugs

Immunomodulators

6-Mercaptopurine, azathioprine, TNF-α blockers, mycophenolate, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine

Neurology drugs

Valproic acid, carbamazepine, mirtazapine, SSRI, and gabapentin

Analgesics

Sulindac, mesalamine, acetaminophen, opiates, celecoxib, and diclofenac

Diuretics

Furosemide and thiazides

Antibiotics

Trimetropin/sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, macrolides, rifampin, pentamidine, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole

Antivirals

Didanosine, pegylated interferon-alpha, and lamivudine

Hormones

Estrogens, steroids, and octreotide

Chemotherapy

Asparaginase, cytarabine, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and vincristine

Cardiac medications

Enalapril, angiotensin receptor blockers, and amiodarone

Other common drugs

Omeprazole, ranitidine, cimetidine, statins, gliptins, metformin, isotretinoin, and saw palmetto

Infections

Viral

Mumps, coxsackie, hepatitis B, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster, herpes simplex, and HIV virus

Fungal

Aspergillus

Parasitic

Toxoplasma, Cryptosporidium, Ascaris, and Clonorchis

Vascular Disease

Systemic lupus erythematous

Polyarteritis nodosa

Atheroembolism

Intraoperative hypotension

14.6 Clinical Presentation

Acute onset of epigastric and periumbilical pain that may radiate to the back flanks and lower abdomen

Nausea and vomiting

Severe pancreatitis: fever, hypoxemia, and hypotension

Signs of retroperitoneal bleeding:

Echymotic discoloration in periumbilical region (Cullen’s sign)

Echymotic discoloration along the flank (Grey Turner’s sign)

Physical examination:

Findings vary depending upon the severity of acute pancreatitis

Minimal to severe epigastric tenderness

Abdominal distention and hypoactive bowel sounds in case of secondary ileus

14.7 Laboratory Evaluation

Serum levels of amylase or lipase ≥3 times the upper limit of normal. (Plasma lipase is more sensitive and specific than plasma amylase.)

Leukocytosis

Elevated hematocrit from hemoconcentration (extravasation of fluid into third spaces)

Practical Pearls

Hyperamylasemia is not specific for acute pancreatitis and may be seen associated with a perforated duodenal ulcer, intestinal obstruction or infarction, cholecystitis, acute peritonitis, and renal insufficiency.

The serum amylase may be normal in patients with alcoholic pancreatitis due to the inability of the chronically damaged pancreatic parenchyma to produce amylase.

Patients with normal hematocrit and serum level creatine and without rebound or guarding are unlikely to experience complications related to pancreatitis, positive predictive value of 98 %.

Diagnosis of acute pancreatitis requires two of the following three features:

Characteristic abdominal pain suggestive of acute pancreatitis

Serum amylase and/or lipase ≥3 times the upper limit of normal

Characteristic findings of acute pancreatitis on CT, MR, or US

14.8 Differential Diagnosis

Perforated gastric or duodenal ulcer

Mesenteric ischemia or bowel infarction

Acute cholecystitis

Acute biliary colic

Bowel obstruction

Inferior wall myocardial infarction

Abdominal aortic dissection

14.9 Phases of Acute Pancreatitis

14.9.1 Early Phase

Systemic disturbances from host response to local pancreatic injury.

Usually occurs by the end of the first week but may extend into the second week.

Cytokine cascades are activated by pancreatic inflammation which manifest clinically by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

10–20 % of patients develop a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

SIRS (defined by two or more of the following criteria):

Pulse rate >90 beats/min

Respiratory rate of >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 of <32 mmHg

Temperature >38.3 C or <36.0 C

WBC count of >12,000 cells/ml, <4,000 cells/mm3, or >10 % immature bands (forms)

14.9.2 Late Phase

Persistent signs of systemic inflammation or by the presence of local complications

Occurs in patients with moderate to severe or severe acute pancreatitis

The SIRS in the early phase may be followed by a compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS) that may contribute to an increased risk of infection (translocation of bacteria)

Practical Pearls

Local complications evolve during the late phase

Radiologic imaging plays a very important role in distinguishing the morphology of local complications for the patient’s management

Organ Failure

Shock, pulmonary insufficiency, renal failure, or gastrointestinal bleeding

14.10 Definition of Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

14.10.1 Atlanta Classification

Mild acute pancreatitis

Absence of organ failure and the absence of local or systemic complications

Most patients do not require pancreatic imaging and are usually discharged within 3–5 days of onset of illness

Moderate to severe acute pancreatitis

Presence of transient organ failure or local systemic complications in the absence of persistent organ failure

Patients require extended hospitalization but have lower mortality rates than patients with severe acute pancreatitis

Severe acute pancreatitis

Persistent organ failure

Single or multiple organ failure

Associated with 30–50 % mortality risk

Most patients with persistent organ failure have pancreatic necrosis

14.11 Scoring Systems to Determine the Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

The initial 12–24 hours of hospitalization is critical during patient management because the highest incidence of organ dysfunction occurs during this period

A number of clinical scoring systems have been developed to facilitate risk stratification during this phase

14.11.1 Bedside Index of Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

Each of these criteria counts as a single point.

BUN >25

Impaired mental status

SIRS

Age: 60 years or older

Pleural effusion

A Bedside Index of severity score >2 points performed during the first 24 hours of hospitalization is associated with a sevenfold risk increase of organ failure and tenfold risk increase of mortality

14.11.2 Harmless Acute Pancreatitis Score

Identify patients at the time of admission who are unlikely to experience complications related to acute pancreatitis.

Normal hematocrit and serum level of creatinine without rebound tenderness or guarding

Unlikely to develop severe pancreatitis

Positive predictive value of 98 %

14.11.3 Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Examination (APACHE) II Score

Applied within 24 hours of patient admission to an intensive care unit.

Score is computed based on several measurements.

Higher scores correspond to more severe disease and higher risk of death.

Twelve physiologic measurements: age, temperature (rectal), mean arterial pressure, arterial ph, heart rate, respiratory rate, sodium-potassium serum, creatinine, hematocrit, white blood cell count, and Glasgow Coma Scale

14.11.4 Modified CT Severity Index

Modified CT severity index

Prognostic indicator | Points |

|---|---|

Pancreatic inflammation | |

Normal pancreas | 0 |

Intrinsic pancreatic abnormalities with or without inflammatory changes in peripancreatic fat | 2 |

Pancreatic or peripancreatic fluid collection or peripancreatic fat necrosis | 4 |

Pancreatic necrosis | |

None | 0 |

≤30 % | 2 |

>30% | 4 |

Extrapancreatic complications (one or more of pleural effusion, ascites, vascular complications, parenchymal complications, or gastrointestinal tract involvement) | 2 |

Total score: points are given on a scale from 0 to 10 to determine the grade of pancreatitis and treatment | |

Practical Pearls

Many scoring systems have been reported, but none has proven to be perfect.

They are superior to clinical judgment for triaging patients to more intensive and aggressive therapy.

14.12 Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the preferred imaging modalities.

Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) is currently the gold standard for evaluating patients with suspected acute pancreatitis.

The role of this modality is to confirm or exclude the clinical diagnosis, to establish the cause, to determinate the severity, to detect complications of the acute pancreatitis, and to provide guidance for therapy.

Very useful to predict clinical outcome.

MR imaging is particularly useful in pregnant patients and in patients who cannot receive iodinated contrast material due to allergic reactions or renal insufficiency.

Abdominal ultrasound is an inexpensive, convenient imaging modality helpful to evaluate the presence of gallbladder and/or common duct stones in acute pancreatitis.

Practical Pearls

CECT should always be performed 48–72 hours after admission to distinguish interstitial from necrotizing pancreatitis when there is clinical evidence of increased severity.

CECT is not recommended earlier because it may provide false information due to pancreatic edema and/or vasoconstriction.

The pancreas may appear normal in approximately 25 % of patients with mild pancreatitis.

14.12.1 Chest Radiographs

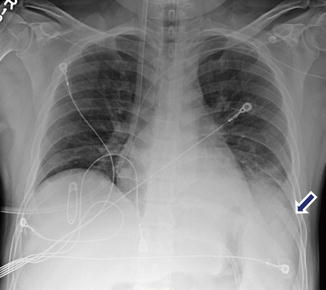

Fig. 14.4

Pleural effusion associated with acute pancreatitis. A 43-year-old female with biliary pancreatitis. Portable chest radiograph shows a mild left pleural effusion (arrow)

Fig. 14.5

Pleural effusion associated with acute pancreatitis. A 54-year-old female with interstitial biliary pancreatitis that eventually became necrotic. Portable chest radiograph shows a moderate left pleural effusion (arrow)

Fig. 14.6

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) associated with acute pancreatitis. A 75-year-old female patient admitted with acute pancreatitis. Two days after admission, she was hypotensive, oliguric, and hypoxic. Patient was transferred to the intensive care unit. Subsequently, she developed severe hypoxia that required intubation. CECT axial image (a) shows a homogeneous pancreas with mild peripancreatic inflammatory changes (arrows). Sequential portable chest radiographs performed (b) at admission, (c) 1 week following admission, and (d) 2 weeks and (e) 3 weeks after admission demonstrate the progression of bilateral diffuse air space disease in both lungs. Findings suggestive of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The patient eventually expired due to multisystemic failure

Findings

Pleural effusion (more common on the left side)

Basal pulmonary atelectasis

Elevation of the hemidiaphragm

Progressive diffuse bilateral air space disease (acute respiratory distress syndrome ARDS)

14.12.2 Abdominal Radiographs (Figs. 14.7–14.10)

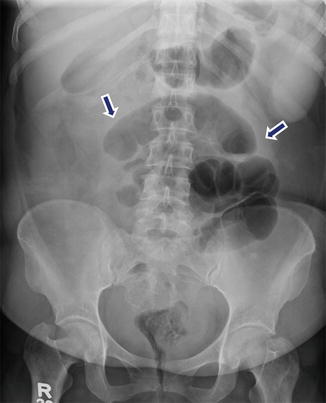

Fig. 14.7

Paralytic ileus associated with acute pancreatitis. A 51-year-old female with history of abdominal distention and iatrogenic acute pancreatitis secondary to recent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Supine abdominal radiograph reveals distended small bowel loops in the mid abdomen (arrows). Findings suggestive of a localized small bowel ileus

Fig. 14.8

Paralytic ileus associated with acute pancreatitis. A 61-year-old male with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Patient developed epigastric pain and abdominal distention. Supine abdominal scanogram (a) reveals the distention of multiple small bowel loops in the mid abdomen (arrows), as well as distention of the transverse colon. Findings suggestive of a paralytic ileus versus bowel obstruction. CECT axial image (b) reveals peripancreatic inflammatory changes (arrowheads) suggestive of acute interstitial pancreatitis. There was no evidence of bowel obstruction

Fig. 14.9

Colon cut-off sign in acute pancreatitis. A 34-year-old male with alcoholic pancreatitis. (a) Supine abdominal radiograph shows distention of the ascending and transverse colon with an abrupt cutoff at level of the splenic flexure (arrow). CECT axial images (b, c) show distention of the transverse colon with an abrupt transition of the diameter at the level of the splenic flexure (b) (arrow) adjacent to the peripancreatic inflammatory changes. Note the spasm and paucity of air in the descending colon (c) (arrowhead)

Fig. 14.10

Infected pancreatic necrosis on abdominal radiograph. A 40-year-old male with history of alcoholic pancreatitis, fever, and leukocytosis. Supine abdominal radiograph (a) demonstrates extraluminal pockets of air between the stomach and transverse colon and in the left upper quadrant (arrows). Finding suggestive of extraluminal gas in the upper retroperitoneum. Axial images (b, c) of CECT performed the same day demonstrate inflammatory changes in the pancreas associated with extensive pockets of air in the pancreatic parenchyma, as well as in the peripancreatic tissues (arrows)

Findings

Duodenal ileus

Localized abdominal ileus (sentinel loop/s)

Gasless abdomen

Colon cut-off sign (paucity of colonic gas distal to the splenic flexure due to functional spasm of the descending colon secondary to the extrapancreatic inflammation)

Abnormal air bubbles in the topography of the pancreas (infected pancreatic necrosis or pancreatic abscess)

Mass effect in the gastrointestinal tract (intra or extrapancreatic fluid collections)

14.12.3 Ultrasound (Figs. 14.11–14.19)

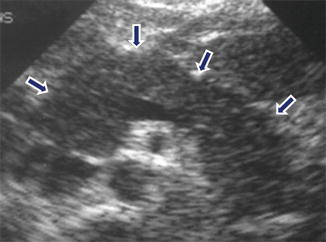

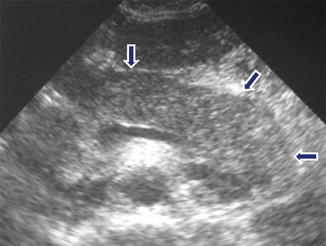

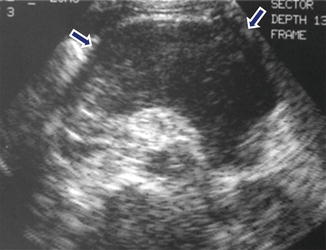

Fig. 14.11

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 45-year-old female with alcoholic pancreatitis. Transverse scan demonstrates an enlarged pancreas with decreased echogenicity and ill-defined margins (arrows)

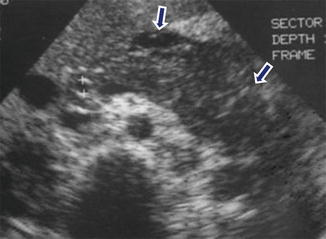

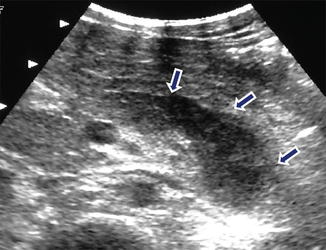

Fig. 14.12

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 48-year-old male with alcoholic pancreatitis. Transverse scan reveals an enlarged pancreas with mild heterogeneous echogenicity (arrows)

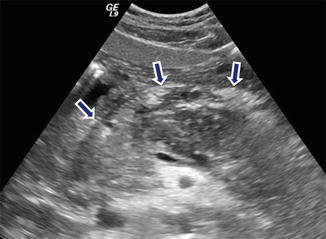

Fig. 14.13

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 29-year-old male with medication-induced acute pancreatitis. Transverse (a) and sagittal (b) scans show diffuse enlargement of the pancreas. Note the mild increased echogenicity of the pancreatic parenchyma (arrows)

Fig. 14.14

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 54-year-old male with alcoholic pancreatitis. Transverse scan shows diffuse enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the pancreas. Note the ill-defined margins of the pancreas and the presence of a small amount of peripancreatic fluid (arrows)

Fig. 14.15

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 38-year-old female with biliary pancreatitis. Transverse image reveals a hypoechoic, enlarged pancreas with ill-defined margins (arrows)

Fig. 14.16

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 41-year-old female with biliary pancreatitis. Transverse image shows an enlarged pancreas with decreased echogenicity and posterior acoustic enhancement (arrows). Findings suggestive of pancreatic necrosis

Fig. 14.17

Acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 65-year-old male with alcoholic pancreatitis. Transverse scan shows a hypoechoic pancreas with ill-defined margins and posterior acoustic enhancement (arrows)

Fig. 14.18

Biliary pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 29-year-old female with acute onset of epigastric pain, jaundice, and hyperamylasemia. An abdominal ultrasound was performed to evaluate the pancreas and the biliary system. Transverse scan of the gallbladder (a) reveals multiple gallstones (arrows). Oblique scan of the right upper quadrant (b) reveals a dilated common bile duct with a distally impacted stone (arrowhead). The pancreas was not visualized due to the presence of abundant abdominal gas. Plain CT axial images (c, d) corroborate the presence of multiple gallstones (arrows), the presence of a biliary stone in the distal common bile duct (arrowhead), and peripancreatic inflammatory changes

Fig. 14.19

Indirect signs of acute pancreatitis on ultrasound. A 63-year-old male with epigastric pain and elevated serum lipase. Transverse and sagittal scans (a, b) show a small amount of fluid anterior to the upper pole of the right kidney (arrows). The pancreas could not be demonstrated due to the presence of abundant abdominal gas. Axial (c) and sagittal (d) CECT images performed the same day show mild enlargement of the pancreas, inflammatory changes around the pancreas (arrowheads), and a small amount of fluid anterior to the right kidney (arrows)

Findings

Normal size or enlarged pancreas

Decrease or increase of the echogenicity of the pancreatic parenchyma

Normal or ill-defined pancreatic margins

Intra- and/or peripancreatic fluid collections

Presence of gallstones and/or choledocolithiasis

Practical Pearls

Ultrasonography has severe limitations and the presence of excess abdominal gas (ileus), or patient’s obesity often occlude the visualization of the pancreas.

This technique has limited capability in delineating the extent of the extrapancreatic inflammation and/or the detection of pancreatic necrosis.

14.12.4 Contrast-Enhanced CT (CECT)

Fig. 14.20

Acute interstitial pancreatitis in four different patients on CT. Patient #1: A 30-year-old female with history of diabetes, bipolar disorder, and idiopathic pancreatitis. CECT axial image (a) shows a homogeneous enhancement of the pancreatic gland and mild inflammatory changes around the pancreas (arrows). Patient #2: A 42-year-old male with alcohol-related acute pancreatitis. CECT axial image (b) shows a homogeneous enhancement of the pancreatic gland and mild peripancreatic inflammatory changes (arrows). Patient #3: A 61-year-old male with acute pancreatitis induced by medications. CECT axial image (c) shows a homogeneous enhancement of the pancreas and moderate peripancreatic inflammatory changes (arrows). Patient #4: A 53-year- old male with biliary pancreatitis. CECT axial image (d) shows extensive inflammatory changes in the left and right anterior pararenal spaces as well as in the lesser sac (arrows). Note the heterogeneous enhancement of the pancreas

Fig. 14.21

Acute interstitial pancreatitis in two different patients on CT. Patient #1: A 27-year-old male with biliary pancreatitis. CECT axial image (a) demonstrates heterogeneous enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma (arrows) and extensive peripancreatic inflammatory changes in the retroperitoneum extending into the mesentery (arrowheads). Patient #2: A 63-year-old male with alcohol-related pancreatitis. CECT axial image (b) demonstrates mild heterogenecity and enlargement of the pancreatic gland with a small amount of fluid in both anterior pararenal spaces, the lesser sac, and subhepatic space (arrows)

Fig. 14.22

Acute interstitial pancreatitis sparing the pancreatic head on CT. A 33-year-old with history of alcohol-related pancreatitis. CECT axial (a–c) and coronal (d) images reveal inflammatory changes around the body and tail of the pancreas (arrows). Note the absence of inflammatory changes around the head of the pancreas (arrowheads)

Fig. 14.23

Acute interstitial pancreatitis associated with extensive perinflammatory changes on CT, clinically mimicking acute appendicitis. A 37-year-old male with diabetic ketoacidosis, dehydration, leukocytosis, and elevated triglyceride levels, complaining of 2 days of periumbilical pain. At admission, the pain was more localized in the right lower quadrant. Findings suggestive of acute appendicitis. CECT coronal (a–c) and sagittal (d) images show poor enhancement of the pancreas and extensive peripancreatic inflammatory changes around the pancreas extending from the root of the mesentery to the right lower quadrant (arrows)

Fig. 14.24

Acute interstitial pancreatitis secondary to hyperparathyroidism on CT. A 41-year-old man with history of intermittent abdominal pain, weakness, bone fractures, joint pain, and episodes of depression. Laboratory: lipase 4,000 units/L, amylase 794 units/L, and serum calcium 14. AP plain film of the skull (a) shows multiple small lytic lesions (arrows). Plain film of the humerus (b) demonstrates an expansile lesion in the proximal shaft (arrows), brown tumor. CECT axial images of the abdomen (c, d) show a heterogeneous, mildly enlarged pancreas and peripancreatic inflammatory changes (arrows). A CT of the chest was performed to evaluate for an ectopic parathyroid adenoma suggested in a Sestamibi study. CECT axial images of the superior chest (e, f) show two a parathyroid adenomas, one posterior to the right lobe of the thyroid (e) (arrow) and the second in the left superior mediastinum (f) (arrow). The patient was taken to the OR with a diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism. During surgery, 6 enlarged parathyroid glands were discovered. Photograph (g) shows the enlarged parathyroid glands surgically removed

Fig. 14.25

Focal acute interstitial pancreatitis associated with pancreatic malignancy on CT. A 65-year-old male with acute epigastric pain, hyperamylasemia, and weight loss. CECT arterial phase (a) and portal phase (b) axial images show focal peripancreatic stranding in the distal body and tail of the pancreas (arrows). Note the presence of a low attenuation mass in the same region (arrowheads). Patient underwent a distal pancreatectomy. Final diagnosis: adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic body associated with distal acute pancreatitis

Fig. 14.26

Acute interstitial pancreatitis associated with pancreatic malignancy on CT. A 70-year-old male with history of repetitive attacks of acute pancreatitis, complaining of severe epigastric pain. CECT axial (a) and coronal (b) images show mild peripancreatic inflammatory changes in the body and tail of the pancreas (a) (arrows). Note the presence of an ill-defined cystic mass in the neck of the pancreas (a, b) (arrowheads) associated with mild dilatation of the pancreatic duct. Patient underwent extended pancreaticoduodenectomy. Final pathology: IPMN with small focus of invasive carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree